| Vol.

XXVI No.

1 September / October 2013 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

My Experience Teaching 3.091x

Developing 3.091x, “Introduction to Solid-State Chemistry,“ was a terrific but exhausting experience. I was lucky to be building upon more than 40 years of material for a very special course. Briefly, 3.091 seeks to help students learn chemical principles through the solid-state. The underlying theme for the course is that the chemical bond determines properties. The emphasis in the course is on linking basic concepts to applications; thus, it is meant to be an engineering course. Indeed, it may be the first engineering course many students take at MIT, as it satisfies the chemistry GIR.

I was asked to consider creating a version of 3.091 for the edX platform in June of 2012, with the objective to enroll students in the fall of 2012. I knew nothing about edX, and my first question was, “Is someone going to help me?” Chancellor Eric Grimson said “yes,” and I did some homework.

What I found was that research consistently shows equivalent learning outcomes for residence-based courses and online learning, across a wide variety of types of courses. More interesting is a growing opinion that superior outcomes are achieved by a combination of residence-based learning and online content.

Thus it seemed that the 3.091x vehicle might yield the online content that could improve outcomes for 3.091 – a test I hope to examine this fall. So the only constraint I imposed was that 3.091x need have the same intellectual content as 3.091, a necessity if I was to use the online material for the campus course.

edX is like nothing I have previously experienced. There are no 50-minute lecture videos such as with OpenCourseWare (OCW). Instead there are 10-minute lecture videos on one topic, followed by a short screencast on a new topic, followed by a self-assessment problem. All of this was arranged in what I call a “learning sequence.” The course was composed of a collection of these learning sequences. edX also operates as a real course. Everyone begins at the same time and ends at the same time. Students throughout the world are learning at the same pace. There are problem sets, midterms, and a final. You may have heard of the “forum.” This is a chat room where students post questions on a particular video and other students, TAs, forum moderators, and faculty can post comments or answers. I learned that participating in the forum is very helpful for the faculty in charge. First, it allows me to understand what questions students have. Second, students really appreciate and are encouraged by the involvement of the professor. My habit was to spend 20-30 minutes in the forum every day. It was something I really grew to enjoy.

What It Takes

Most of the questions I get from colleagues concern how much effort edX takes. My answer is, more than I thought it was going to be. It is important to note that much help was provided by edX personnel, and I understand that the support model for these courses going forward will be different. Nonetheless, here is what it took to create 3.091x.

Beginning in June 2012, I had a full-time TA and a full-time edX person for the summer to work on course development. Additionally, we had a full-time video editor and about 1.5 FTE of software engineering support. Additional staff was added as the course came on line. These included part-time administrative support, five paid forum moderators, and four “community TAs” (volunteers from various places around the globe). Finally, we had two-to-five “beta checkers” at various points during the course. Their responsibility was to help find bugs in problems.

I was fortunate that we had access to high quality video from my fall 2011 lectures on campus. Only a handful of lecture segments were derived from fall 2012. Thus, we were able to create 330 lecture segments (50 of which we did not end up using) from my past lectures’ video library. Despite this large video resource, I ended up creating 65 screencasts. These screencasts were originally intended to replace sections of normal lectures, but I found them also very useful for doing example problems. Finally, in 2011 I had professionally produced six mini documentaries for 3.091 with funds from the Dreyfus Foundation. These were also included in 3.091x.

Screencasts were a surprise to me. I have been on the faculty since 1986. Give me a piece of chalk and stand me in front of a blackboard and I am in “lecture mode.” A video segment of a lecture captures that perfectly.

A screencast captures something different. I am in my office, writing on a tablet, and speaking to the imaginary student over my shoulder. The words I use and my tone is completely different. There is no “projecting” my voice so that a student in the back of 10-250 can hear me. I am having a conversation.

Mixing these screencasts with lecture segments makes for a much more enjoyable experience for the listener. Frankly, if I were starting a course from scratch, I would do it all as screencasts. Also, as a practical matter, screencasts are infinitely easier to edit than lecture segments. Five to 10 minutes of screencast took me approximately 60-90 minutes to prepare once I got used to the video editing software. So I spent much of August 2012 as well as the fall term making screencasts.

3.091x was launched October 15, 2012, and ended January 11, 2013. The late start date was planned so that the fall residence 3.091 course would not be contaminated with the online version of the class. The intention was to compare outcomes between the two student populations. It was not going to be a particularly rigorous study. Rather, it was going to be a “pilot trial”; gather enough data to make some hypotheses.

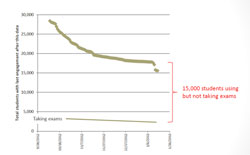

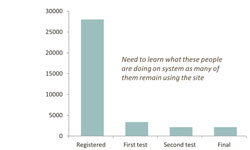

The initial registration was impressive, as shown in the chart below (Figure 1). Over 28,000 individuals registered. As is common for MOOCs, however, only 10% ended up taking the exams. This was a bit disappointing to me, until I saw the chart indicating the last time a 3.091x registrant interacted with the system (Figure 2). It shows that approximately 15,000 registrants are using the online material, but not taking exams.

(click on image to enlarge)

What are these 15,000 registrants doing? Our exit survey with over 1800 people responding gave me a clue. It turns out that over 52% of those registered were students enrolled in other schools. 13% were graduate students, 29% were university students, 1% were community college students, and 10% were high school students. We concluded that many registrants are using the online content as a resource for a class they are currently taking elsewhere. Why would they take my exam if they were going to take one for the class they are already in?

A particularly fulfilling finding was the participation rate of teachers. 9% of those taking the final in 3.091x were teachers. 4% were university professors and 3% were K-12 teachers.

Thus over 60 high school teachers took the final. If that same ratio holds true for the entire population using the system, it would total 540 teachers. I corresponded with several high school chemistry teachers throughout the country and the world. They were using the material to enrich their high school class.

| Back to top |

Outcomes

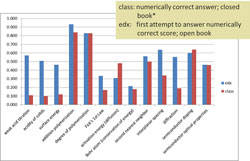

How well does all this work? That is a very difficult question to answer, but I will share some data. I tried to design the finals for both classes (3.091 and 3.091x) so that I could compare learning outcomes. There are several problems with this approach. First, I give partial credit for problems on the 3.091 final. edX problems do not have partial credit. Instead we give students a number of attempts to get the correct answer. For example, if they slip a decimal point in a calculation, they get a chance to fix it. We assume that the two types of measurement converge to measuring the same thing. Second, 3.091 is closed book except for a single sheet of notes. 3.091x is open book and open Web. The only way to control for this is to use questions that don’t depend on whether you have access to a book or not. Problems that ask the student to calculate something are what I took as an approximate “open book independent” problem. Finally, 3.091 has a three-hour final. Students are given an entire weekend to take the final in 3.091x. I could not think of a way to control for time, so that needs to be a factor in interpreting the outcomes.

(click on image to enlarge)

Figure 3 compares outcomes between 3.091 and 3.091x students. These outcomes measures try to control for partial credit grading of 3.091, by only counting students that reported the numerically correct answer for that problem on their final. The 3.091x scores only report the number of students that answer correctly on the first try.

Only three outcomes are meaningfully different between 3.091 and 3.091x; weak acid titration, acidity of solids, and surface energy. The 3.091 students scored particularly low on these outcomes. A second look at the written exams shows that these problems had a high proportion of students having provided no response, not a wrong one. I assume that the 3.091 students followed the standard advice; “Look over the entire exam and do the problems that you understand first.” Could the problem be that it is not that they did not know this material, but rather that I did not give them enough time to actually measure what they know?

3.091x students rated the course highly during the exit survey. 27% rated it “Best course I have taken.” 60% rated it “Great course” and 11% rated it “About what I expected.”

My plans on how to use the online content in the residence-based course will be tested this semester. Briefly, I will be using the online content of 3.091x as the text for 3.091. 3.091 has not had a formal text for many years. We normally used a combination of a standard university chemistry text, course notes written for the class, and a reader of individual chapters from many other texts. None of these sources covers the detail that we actually cover in the class.

The second part of the experiment is to change student assessment. Instead of written exams, we will be using online assessments in a proctored environment. Students will use drop-in hours to evaluate their mastery of 27 skills that we have defined for the course. Each assessment is a single problem selected at random from a problem database on that topic. If a student does not pass a given assessment, they are given the opportunity to try again the next day. There is no time pressure on these assessments. The idea is to overcome the deficiencies of our classical examination model.

I have spoken with numerous other faculty from other universities involved in online courses. Nearly everyone has enjoyed the experience, although we are all still unsure where to best deploy these types of courses. My sense is that the large early courses offered at many universities, like 3.091, are a natural place to start. These courses offer the broadest appeal to students throughout the world. It is also not unrealistic to me that by using an edX type medium an MIT undergraduate experience may someday be one year off campus and three years on campus. I feel online content in our residence-based instruction will probably emerge first in other ways. The screencast medium for instruction is particularly important in my mind. It can free up valuable contact time with students. Rather than taking lecture time to get into the mechanical details of a topic, I can reserve that for a screencast. Instead, I can use the time for discussion on the ideas behind the topic and its implications.

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |