| Vol.

XXVII No.

4 March / April 2015 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

Campus Conversation on Climate Change

When President Reif announced the MIT Environmental Solutions Initiative (ESI) last spring, he called for a campus conversation on climate change to gain input as to what our community thinks MIT should do to address the risk of climate change. This spring, as the MIT Climate Change Conversation unfolds, I take this opportunity to outline the facts that form a starting point for the Conversation, to explain the process so far, and to challenge you, my faculty colleagues, to engage and express your views, so that MIT can choose a path to combat climate change that reflects your wisdom, ideas, and values. We need every segment of the MIT community to participate in the Conversation, and that is why I am personally reaching out to you.

Let’s begin with science. I will provide a very brief summary of the scientific case for global warming. This is meant to inform subsequent discussion and not to be an exhaustive justification. For the latter you should read the scientific literature, various climate reports [see, for example, ipcc.ch and www.globalchange.gov/what-we-do/assessment], or talk to climate scientists at MIT or elsewhere.

The science, briefly

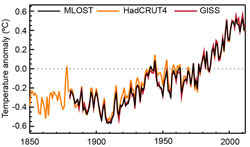

The world has warmed at various times throughout its history and it is warming now. Recent warming (Figure 1) is a matter of concern. The last 10 years represent the warmest decade since at least the 1880s, when global temperature measurements became available. On a global average, the planet is about 0.8oC warmer than it was in 1880 based upon dozens of high quality, long records using thermometers worldwide, on land and sea (IPCC WG1, 2013).

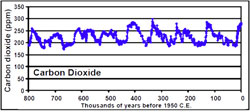

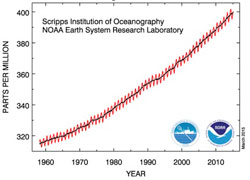

The amount of CO2 in the atmosphere has also varied over geological time. A particularly long, high-quality record from an ice core from Antarctica (Figure 2) demonstrates the variability. The CO2 content of the atmosphere has been increasing since the last ice age, but has accelerated since the dawn of the industrial revolution. The amount of CO2 in the atmosphere now (400.26 ppm in February 2015; see Figure 3) is greater than at any point in the last 800,000 years, the length of the measured record. (There are geologic and sediment records that place some constraint on CO2 farther back than 800,000 years, but these records are considerably less accurate than the ice core data.) Virtually all scientists accept these observations as accurate.

The substantial increase in CO2 during the industrial age is believed by the overwhelming majority of scientists to be primarily due to the burning of fossil fuels, and to be the cause of most of the current warming of the Earth. Global warming is not a debate. What is legitimately debatable is the fraction of the increase that is human induced.

Equally debatable are the environmental consequences of the continued increase of CO2 and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere because not all climate forcings are well understood. Some climate feedbacks such as cloud changes in a warming world are subject to uncertainty, as are scenarios for future emissions. Climate models that contain different physical parameterizations and make different assumptions forecast outcomes ranging from grim to somewhat troubling. [Check out the “Greenhouse Gamble Wheel” developed by the MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change.] The latest National Climate Assessment declared that effects of global warming are already being observed. Like many of you, I travel around the world, and I am struck that the United States is nearly unique in not readily accepting the threat of global warming.

That said, given the uncertainties, what, if anything, do we do about it? It’s really all about risk. The overwhelming majority of scientists regard global warming as presenting serious risks. It is certainly possible that most scientists are wrong, but are we willing to bet the future that this is the case? In other aspects of our lives when we face risk we think carefully about the consequences of action and inaction and proceed accordingly. What would happen if we stopped pumping CO2 into the atmosphere right now? It would take more than a thousand years to remove from the system the CO2 that we have added and for surface warming to dissipate (Solomon et al., PNAS, 2009; 2010). If we wait until we understand all of the uncertainties while continuing on a path of unabated CO2 increase, we could be setting up future generations to deal with a global calamity. This is where science ends and values begin, because how we deal with risks, particularly risks we may be causing now that affect other people (in other parts of the world, or future generations), is a question of values.

What are the attitudes in our community?

Now let’s take the temperature of members of the MIT community. This is my assessment based on numerous meetings, discussions, and e-mail exchanges on the topic of global warming. There are many students, postdocs, and young alumni who are worried that we adults are ruining their planet. There are faculty members who study climate change whose research has been vilified and politicized by individuals and organizations, most of whom have not attempted to grasp the complexity of the science. There are young people who are embarking on careers to study the Earth’s climate who must face the concern that they will be judged on their alignment with political ideology rather than on the scientific merit of their work. There are alumni who are expecting MIT to stand up and take a leadership position on this matter of global importance. There is a small fraction of our community who don’t believe that global warming is a problem.

| Back to top |

The campaign for divestment

Enter Fossil Free MIT (FFMIT), a campus organization that has joined a national movement on college campuses whose objective is divestment from fossil fuel stocks to highlight the threat of climate change. FFMIT consists primarily of students, and their leadership has met with many members of the senior administration and other campus leaders.

FFMIT has a petition that reads:

In order to limit global temperature rise to less than 2 degrees C, no more than 1/3 of global carbon reserves owned by fossil fuel companies and governments can be burned prior to 2050. Because it is unconscionable to finance our Institute with investments that will lock us in to catastrophic climate change, we call on MIT to:

1. Immediately freeze any new investment in fossil fuel companies, and

2. Divest within five years from current holdings in these companies.

Their petition contains more than 3000 signatures. From what I can surmise, some of the signees have thought very deeply about climate change and signed the petition with an understanding of many of the issues relating to divestment. Others signed with what might be a less thorough appreciation of the pros and cons of divestment, often on their way down the Infinite Corridor where FFMIT periodically has a presence. Finally, some signees have told me that they don’t think that MIT should necessarily divest, but they are deeply troubled about the lack of action on climate change at any level (MIT, the U.S., the world) and thought that they should do something to express their concern. We do not know the relative contributions of signers from the various categories. However, the sheer quantity of signatures tells us that this issue merits thoughtful discussion.

What have other universities done regarding fossil fuel divestment? Most that have divested do not have substantial endowments, with the exception of Stanford, which decided to divest only from coal and only from coal investments that Stanford makes directly (as opposed to investments made by outside investment managers who invest for Stanford). None of the Ivies have divested, but Yale communicated to its outside investment managers the importance of accounting for “the risks of climate change in investment analysis.”

What does our community think MIT should do about climate change?

The question we all care about is, “What does our community think MIT should do about climate change?” Should we accept FFMIT’s call to divest? Should we do something else instead, possibly a proactive response that contributes to reducing the Institute’s carbon footprint? Should we do something far more ambitious, and if so, what? Should we do nothing until we are more confident about the magnitude of the risks?

Last spring, when President Reif called for the campus conversation on climate change, he asked Provost Marty Schmidt, ESI Director Susan Solomon, MITEI Director Bob Armstrong and me (collectively forming the “Conversation Leadership”) to lead this activity. Because much of the best work at MIT is done through collaboration across the Institute, we decided to appoint a committee to implement the conversation. The Committee on the MIT Climate Change Conversation, listed in Table 1, is chaired by Professor Roman Stocker and contains faculty from all five Schools, a postdoctoral associate, a graduate student, an undergraduate student, a staff member, and a senior member of the technical staff of Lincoln Laboratory. [The Climate Change Conversation Committee has a Website that contains a lot of useful information.

Their charge is as follows:

The Committee will plan and implement the MIT Climate Change Conversation, reporting to the Conversation Leadership (Provost Marty Schmidt, Vice President for Research Maria Zuber, Environmental Solutions Initiative Director Susan Solomon and MITEI Director Bob Armstrong).

The Committee should seek broad input from the Institute community on how the US and the world can most effectively address global climate change. The Conversation should explore pathways to effective climate mitigation, including how the MIT community – through education, research and campus engagement – can constructively move the global and national agendas forward. Possible activities for the Campus Conversation could include a lecture series, panels and a survey in which all points of view of the MIT community are sought, presented and discussed.

The Committee should produce a final report to be delivered to the Conversation Leadership. The report should list, in unranked order, key suggestions with associated pros and cons that encompass the range of views of the community. The Committee should accomplish its work during the FY14-15 academic year and submit its report by Commencement 2015.

The Conversation Leadership will solicit reactions to the report from the MIT community and, from the collective input, recommend to the President a path forward.

Last fall the Climate Change Conversation Committee launched an idea bank seeking input for the most effective ways to deal with climate change, as well as a survey to gain input as to how the community wanted to engage on the topic. The public part of the conversation is taking place this spring, with the schedule of events listed in Table 2.

To know what the community thinks, we need the community to speak

Up until now, there has been a dedicated and passionate group on campus and from the alumni ranks who have been calling on MIT to take action. But we need all members of our community to get involved with this conversation. To inspire you to start thinking, let me pose some challenging questions:

- How do we reconcile the social harm associated with burning fossil fuels with the social benefit of their current use, especially in developing economies?

- Everything we do has a cost. What’s the appropriate balance of MIT investment to respond to climate change with investment in other Institute needs?

- What kinds of action can we take that are commensurate with the global nature of climate change?

- Would it be appropriate to call out fossil fuel companies while continuing to use their products and to partner with them on clean energy solutions and fossil fuel studies that mitigate environmental harm?

- Is the threat of climate change such that we should diverge from our modus operandi of objective, data-driven analysis and problem solving to take a social activism role in combating it?

- Where’s the shared sacrifice? How do we insist that MIT as an institution take action without each of us changing our own behavior?

- How can MIT best exhibit leadership on the issue of climate change?

We need to be discussing these and many other questions about what MIT should do, or, if you wish, not do. We can fully expect our students to come out in force and let us know what they think. Good for them! But on this issue, we have heard from a small fraction of MIT’s 1,000-plus faculty so far. We can’t develop a strategy that considers the wishes of the community if we don’t know what all community members think. There should be no expectation on your part that an outcome that is acceptable to you will emerge in the absence of your input. Please make your opinion known by participating in the public events (Table 2) or contacting anyone on the Climate Change Conversation Committee (Table 1) or the Conversation Leadership.

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |