| Vol.

XXVIII No.

2 November / December 2015 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

Gender Imbalance in MIT Admissions Maker Portfolios

In August 2013, the Admissions Office added a Maker Portfolio supplement to the undergraduate application. Many colleges and universities, including MIT, have long offered applicants the opportunity to share their talents in the admissions application in domains such as music, art, and sports. But few, if any, colleges and universities have created instruments and processes to identify and evaluate technical creativity and skill with comparable rigor.

The Maker Portfolio was designed to address this gap by allowing applicants to submit a supplemental portfolio of technically creative work. Each portfolio is reviewed at least once by a member of the Engineering Advisory Board, a body constituted by members of the faculty, instructional staff, and distinguished alumni with specific expertise and experience in particular modes of “making.” These evaluations are added to the applicant's folder for consideration in the admissions process. While submitting a Maker Portfolio is neither necessary nor sufficient for an aspiring applicant, an outstanding Maker Portfolio can provide a compelling reason to admit an otherwise qualified candidate to the Institute.

In many respects, the Maker Portfolio has been a resounding success. Over the last two years, more than 2000 students have used it to show us the things they make, from surfboards to solar cells, code to cosplay, prosthetics to particle accelerators. We believe the Maker Portfolio has improved our assessment of these applicants and offers us a competitive advantage over our peers who have not developed the processes to identify and evaluate this kind of talent. After the preliminary success we've seen at MIT, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy has recommended, in its "Nation of Makers" report, that more universities consider implementing a Maker Portfolio in their admissions process.

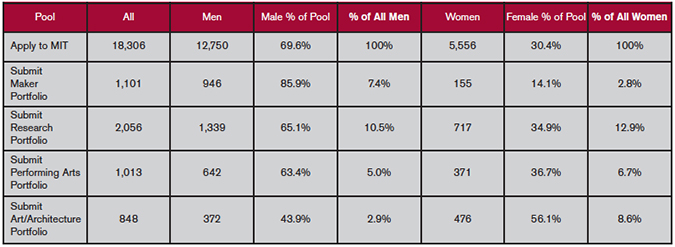

One persistent challenge to the Maker Portfolio, however, is the fact that women submit them at a much lower rate than men do, and at a much lower rate than they submit other portfolios and apply to MIT overall, as depicted on the chart below.

As you can see, 85.9% of all Maker Portfolios last year were submitted by men, and only 14.1% by women. Another way of looking at the same data is that 7.4% of all men who applied to MIT last year submitted a Maker Portfolio, while only 2.8% of all women did. Yet another way to look at the same data: of the 9531 male applicants last year who indicated engineering as a field of interest (74.7% of all men), 812 submitted a maker portfolio (8.5% of all men). Of the 3414 females last year who wanted to major in engineering (61.4% of all women), 130 submitted a maker portfolio (3.8% of all women). We note that this data does not include other possible socioeconomic intersections (e.g., by race, wealth, or parent's education) that we intend to make the subject of future research. Whatever way you slice the data at hand, however, the consistent trend is that women submit the Maker Portfolio – and only the Maker Portfolio – at a lower rate than men, and far below the rate they submit any other type of supplemental portfolio. The question is why?

One reason could be that adolescent women applying to MIT don't have (or do not believe they have) the portfolio of work that a Maker Portfolio is supposed to showcase. Despite recent public awareness and renewed initiatives such as Girls Who Code, the STEM “pipeline” remains tightly constricted by gender. According to the College Board, only 20% of the students who took the 2014 AP Computer Science (APCS) exam globally were women. MIT's robust applicant pool actually slightly over performs the general population, as approximately 25% of our applicants who reported taking APCS in high school are women, but still, only ~26% of our female applicants self-reported taking a coding course in high school, lagging ~32% of male applicants. Obviously, computer science is not the only mode of “making.” It is, however, a mode of making that has: a) comparatively good public data available, and b) a great deal of public attention currently invested in expanding the pipeline.

Another possibility is that women may not identify with the Maker identity with which the Portfolio is branded.

The Maker Movement overall has occasionally been criticized for its lack of demographic diversity: as former MIT Professor Leah Buechley noted in a 2013 talk at Stanford on her study of representations of makers in media, 85% of the people featured on the cover of MAKE magazine in her study were men, and (to its credit) Maker Media, the organizational entity supporting the Maker Movement, has been grappling publicly with how to diversify the Maker population. On the other hand, question 46 on MIT’s 2015 Undergraduate Enrolled Student Survey (ESS) asked members of the MIT Class of 2018 to indicate what, if any, identities resonated with them. In that survey, 30% of respondents identified as “maker,” and the rate was the same for both men and women who responded.

| Back to top |

Another possibility is that the association of a Maker Portfolio with specifically technical creativity (as opposed to more general artistic creativity) may be dissuading young women from submitting one. It has been long-established that fewer women feel confident about their ability to succeed in engineering than in other areas of math and science. Twenty years ago, the Final Report on Women Undergraduate Enrollment in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at MIT, chaired by Professor Abelson, found that women were systematically less confident about their preparation to succeed in EECS than their male counterparts; last semester, a team of EECS undergraduates, in a survey of their classmates, found that "difference in confidence in the major is disproportionately higher than the difference in prior preparation [between women and men]." Some of our data are consistent with this hypothesis: of men and women who do submit Maker Portfolios – that is, of those who already identify as Makers – they are equivalently likely to want to major in engineering (85.9% of men against 83.9% of women).

So it's also possible that technically creative women may still not believe that the Maker Portfolio is “for them,” despite specific actions taken by Admissions to try and counteract this belief, e.g., by prominently featuring female makers and their projects during public talks about the Maker Portfolio at World Maker Faire New York in 2014 and 2015. On this point, we can't help but notice the striking mirror-image quality of the Maker Portfolio and Art/Architecture portfolios compared by portfolio submission rates within gender, and wonder again about gendered associations of “making” vs. other modes of creative expression.

Over the last few decades, MIT has made great strides in leveling the playing field for women at the Institute. One reason we have chosen to publish this data is to highlight the continuing importance of identifying, acknowledging, and developing technical talent in pre-college women, and for MIT, both as an organization and as the individuals that constitute it, to maintain and improve its support for initiatives and programs that work toward these ends. Another reason is that we in Admissions are interested in community feedback on if and how we might make the Maker Portfolio seem more accessible to women (if indeed it does not at present). There is some reason to believe that the “problem” begins before it reaches our process, but that doesn't mean we shouldn't try to do anything about it. We are open to considering anything that can be done to help, and welcome your suggestions (addressed to chris.peterson@mit.edu, ccing hal@mit.edu) to that end.

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |