| Vol.

XXXI No.

1 September / October 2018 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

MIT's Relationship to China

Dear Colleagues,

I write on a subject of growing importance and complexity: MIT’s relationship to China. In hopes of spurring dialogue, in this piece I outline how we are approaching this subject at the Institute level, offer some U.S. government context and suggest some principles to guide us from here. Given China’s growing strength in research and innovation, and the significant fraction of our community that hails from China, the practical and philosophical questions at play are relevant to all of us at MIT.

Building on A Global Strategy for MIT

Last year, my office published a foundational report developed with broad faculty input: A Global Strategy for MIT. Overall, it concluded that, as MIT’s international activities continue to grow, we must become more purposive and proactive in how we select, organize, and manage our major international engagements. In terms of research and education, it recommended that MIT develop a more robust platform for supporting individual faculty members in their international initiatives, and that we should continue to build out MIT’s distinctive "global classroom," in which our students learn about the world through hands-on, practical problem-solving projects in situ, augmented by country-specific cultural and historical education and language training.

While calling broadly for increased international engagement, the report highlighted China (as well as Africa and Latin America) as warranting special attention in view of the high potential for impactful engagement by MIT.

Over the past year my office has led a series of efforts to strengthen our ability to evaluate and develop MIT’s China-related activities. We began with inside voices: interviews with more than 50 faculty colleagues who assessed China’s likely future progress in their fields. For an outside perspective, we invited some of America’s leading China experts to MIT to speak with an ad hoc working group of faculty and administrators about economic and political developments in China, and we consulted with policymakers and their advisors in Washington. On the ground, we have also been exploring several potential research and educational collaborations with Chinese partners, on their own merits and also as a way to clarify what we might and might not want to do in and with China.

And this November, following a recommendation of the Global Strategy report, we will convene MIT’s first Global Summit in Beijing.

The first of its two days will feature activities and events around the city hosted by several MIT programs, including DUSP’s China Future City Lab, Sloan’s International Faculty Fellows program, the student-run MIT China Innovation and Entrepreneurship Forum (MIT CHIEF), the Alumni Association, and others. The second day is a plenary conference; designed to demonstrate MIT’s interest in working with and learning from China and to communicate the values and principles most important to us in research and education, it will feature 15 MIT faculty as well as leaders from China’s scientific and business sectors. Two key Summit themes will be: what we can learn from each other, and what we might do together to address major global challenges such as climate change, pollution reduction, and urbanization that are important to both countries and to the rest of the world. In concert with the Summit, the Executive Committee of the MIT Corporation will travel to Beijing and Shenzhen as part of a year-long effort to educate itself about the risks and opportunities of engagement with China.

The context: escalating U.S.-China tensions

Meanwhile, the bilateral relationship between the U.S. and China has entered a difficult period. The two countries are in the early stages of what seems likely to become a fully-fledged trade war, and the U.S.-China relationship is now framed by U.S. policymakers principally in terms of strategic rivalry with an adversary. The expectation is of growing economic, military, and ideological competition. In Washington this narrative has quickly become widely accepted, on Capitol Hill as well as in the Executive branch. Indeed, it is one of the relatively few issues on which there is currently fairly broad bipartisan agreement.

Science and technology as geopolitical concerns

Science and technology are at the heart of this new strategic competition, as President Xi Jinping focuses on achieving world-leading science and technology in his drive to promote economic growth, strengthen China’s military capabilities, and consolidate political control. At home, U.S. policymakers in both parties are focusing on China’s theft of intellectual property and industrial espionage, and the forced transfer of technology to their Chinese rivals by U.S. companies seeking access to the Chinese domestic market. Texas Senator John Cornyn, the majority whip, reflected a widespread view in Congress in arguing last month that “[w]e simply can’t let China erode our national security advantage by circumventing our laws and exploiting investment opportunities for nefarious purposes . . . . The backdoor transfer of technology, know-how, and industrial capabilities has gone unchecked for too long.” Many in the U.S. government now see the Chinese as bent on Asian and eventually world domination, at America’s expense, and see little reason to cooperate with the Chinese, especially in science and technology; as they see it, the goal should rather be to isolate China’s scientific establishment, to cut it off from ours.

What does the worsening of U.S.-China relations portend for MIT?

In the short run, some legislators and federal officials are seeking to control the access of Chinese students and visitors to American university labs and technologies through visa restrictions and other means. At a congressional hearing earlier this year, FBI Director Christopher Wray described "non-traditional collectors of information, especially in the academic setting, whether it’s professors, scientists or students . . . . exploiting the very open research and development environment that we have, which we all revere." Director Wray warned of the need to "view the China threat as not just a whole-of-government threat, but a whole-of-society threat on their end, and I think it’s going to take a whole-of-society response by us."

of R&D by next year.

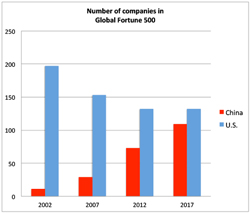

(click on image to enlarge)

Concerns for MIT on campus

There are legitimate concerns here that must be addressed promptly and effectively, but also real risks that the remedy will be worse than the disease. We must firmly resist threats to free and open exchange and collaboration on campus, along with any proposals designed to discriminate against MIT students, researchers, and faculty from China (or any other country). We must also zealously protect our ability to invite the world’s most outstanding students and faculty to join the MIT community. Over the past decade the numbers of Chinese graduate students and postdocs at MIT have both more than doubled: today, 10% of our graduate students and 20% of our postdocs hail from China. In the same period, the rate at which MIT researchers co-authored publications with colleagues from leading Chinese universities rose tenfold. These trends reflect assessments of the advancing quality of Chinese scientific research by many members of our faculty.

Concerns for MIT in China

In the longer run, a central question for MIT is how we will connect to China’s rapidly developing scientific and technological infrastructure. A major focus of current U.S. government policy is to try to prevent or at least slow China’s advance. A particular target is China’s ambitious Made in China 2025 strategy, which seeks to achieve global leadership in key fields of science and technology including AI, clean energy, advanced manufacturing, aerospace, quantum science and engineering, and genetic engineering. White House officials and congressional leaders are considering measures aimed not only at preventing unfair trade practices, but also at building firebreaks against China’s industrial rise. But as President Reif trenchantly observed in a recent New York Times editorial, “If all we do in response to China’s ambition is to try to double-lock all our doors, I believe we will lock ourselves into mediocrity.” He urged the government to focus on developing a domestic strategy of investment in sustaining American leadership in science and innovation. And he suggested that U.S. views of China as an adversary should be tempered by the recognition that China will increasingly have strengths in technology that we can learn from.

Faculty perspectives

On these latter points, our faculty clearly agree. Many of the faculty we interviewed had no doubt that Chinese researchers in their fields would be matching the best of American capabilities in a decade or less, and some stated that this had already occurred. Some of the faculty saw immediate opportunities for productive scientific collaborations with capable and well-funded Chinese colleagues (in some cases their own former students), while others were attracted by the possibility of engaging with the downstream elements of China’s rapidly developing innovation ecosystems, including sophisticated and adventurous industrial users of advanced technologies; abundant venture capital; troves of data; vast and fast-moving consumer markets; flexible and responsive supply chains; and unmatched abilities to scale up to high-volume production of innovative manufactured products. Some faculty emphasized the educational value of introducing our students to China, and that American graduates of MIT who are knowledgeable about China’s history, culture, language, politics, and economic development and who also have a practical, hands-on knowledge of Chinese business practices and innovation capabilities will surely bring broader benefits to the U.S. Other faculty saw opportunities in China to use their knowledge and skills to tackle some of the world’s most challenging problems – problems such as environmental pollution, food safety, and urbanization on an almost unimaginably large scale.

The views of our faculty interviewees were far from monolithic. Some expressed serious concerns over increasing censorship, human rights violations, and the re-assertion of Party political control over Chinese university campuses. Some raised ethical concerns about the possibility that scientific collaborations with China might help the Chinese government -- even if only indirectly and marginally – to use advanced technologies against its own people, or against the U.S. in future military confrontations. And some judged that Chinese capabilities in their research fields were not strong enough to justify collaboration.

On balance, however, the inclination of our faculty interviewees was to engage with China, and the most compelling justification to do so was also the simplest: it will make us a better institution. We become stronger when we succeed in attracting the world’s most talented people to come and work with us, and many of these people come from China. We become stronger when our faculty and students are able to study and conduct research at the world’s most advanced research facilities, and increasingly these will be located in China. We become stronger when we work with and learn from the world’s most innovative firms, and more and more of these are Chinese.

| Back to top |

What are MIT’s responsibilities?

This view of the merits of engaging with China is obviously quite far removed from the primarily adversarial and defensive posture of the U.S. government today toward China, and it raises an important question: when this kind of gap opens up, what are MIT’s responsibilities as an American institution of education and research? Of course, our faculty are and must remain free to follow their intellectual agendas and moral predispositions. That is the Institute’s most fundamental operating principle. But sometimes we must also act at the institutional level, and in such cases, as MIT considers its engagements with China, what is our responsibility to concern ourselves with the policies of the U.S. government?

Needless to say, one obligation is to ensure that MIT itself as well as individual members of the MIT community are in full compliance with all relevant federal (and state) laws and regulations. Additionally, as an American institution we must be cognizant of national policy and give due consideration to the national interest in our internal decision-making. However, with one important exception, national policy ought not to dictate our actions. Our job is to act in the best interests of MIT itself, even while recognizing that this may not always lead to outcomes that are consistent with the government policies of the day. When our plans and programs are not aligned with those policies, we have a responsibility to be fully transparent, to inform relevant agencies so that there are no surprises, and to engage with government officials in discussion of these differences.

The exception to the principle that national policy does not dictate MIT actions would arise if we were to encounter situations in which the interests of the United States and China were in direct conflict. (For an institution like MIT, with its strong practical and worldly orientation, this is not an implausible scenario.) In such cases, there should be full confidence, both at home and abroad, that MIT, as an American institution, will never put any other country’s interests ahead of those of the United States.

As a practical matter, there will generally be good alignment between what makes sense for MIT and what is good for the United States, not least because a hypothetical action taken by MIT that was harmful to U.S. interests would be likely to end up harming MIT too, in one way or another. That said, we cannot assume a priori that activities which we believe to be in MIT’s long-term interest will always be aligned with whatever the government policies of the day happen to be. Preparing for such possibilities must be an important part of our China strategy.

At the outset of this article I mentioned that we had embarked on a year-long process of learning how best to manage our relationship with China. The year isn’t over yet, and the events in Beijing this coming November will certainly add to our stock of insights. But already some important lessons can be discerned. Here are a few:

- Any major MIT engagement with China is more likely than not to receive attention from both the U.S. and Chinese governments, because of our reputation and because of our involvement with strategic technologies. We must be prepared to explain in Washington what we’re doing, why we’re doing it, how we decided to do it, and that we understand that there are real risks of engaging with China and are taking concrete steps to deal with them. We must be prepared for negative reactions.

- To reach sensible decisions about our China-related activities, we must have well-designed internal processes capable of weighing risks and benefits carefully, making distinctions among different kinds of activities while ensuring that our core values and principles and general policies are brought to bear, and drawing on outside expertise when needed. An important part of these processes is the faculty International Advisory Committee (IAC). Following the recommendation of last year’s Global Strategy report, the IAC was reconstituted a year ago as a Standing Committee of the Institute to provide an independent faculty voice in advising the senior administration on MIT’s significant international engagements. Under its chair, Prof. Rohan Abeyaratne, the IAC has been considering our China-related activities over the past year and will continue to play an important role in this domain. If you are considering new engagements with China, I urge you to contact the IAC about your plans.

- There is much about this situation that is new, and it would be a mistake for anyone – either inside or outside academia – to assume that they know the right approach to engagement with China. In both Washington and Beijing it is now common to hear about the onset of a new Cold War. But, of course, the twenty-first century competition with China is very different from the twentieth century strategic nuclear and ideological competition with the Soviet Union. Despite imbalances and vulnerabilities, the Chinese economy is far more robust than the Soviet economy ever was, and it will likely soon become the world’s largest. This is a new situation for the United States – dealing with a military and ideological rival that is also a worthy economic competitor, with which our own economy is far more deeply intertwined than was ever the case with the Soviet Union.

For MIT and other leading American research universities, too, the situation is new: the emergence of world-class scientific, technological, and industrial capabilities with much potential benefit for us and the world in a country with which the U.S. has major political and ideological differences. Especially in this dynamic environment, when government policies in both countries are rapidly changing, it isn’t obvious when to cooperate and when not to cooperate, and – when it is appropriate to cooperate – how to do so. How can we engage in China without checking our principles at the door? How can we collaborate with Chinese companies without losing control of our intellectual property? How can we work with Chinese collaborators at the technological frontier if we are anxious about how the Chinese government might use the results? At a time of growing confrontation, we must somehow create space for ourselves to experiment, and to recalibrate and refine what we are doing as we discover what does and doesn’t work.

- Finally, when it comes to China collaborations, we should not be misty-eyed about China’s importance to us. We need instead to be realistic in our expectations and clear about our interests and objectives, and the more specific and "granular" the goals for these collaborations, the better. For example, we might expect that such collaborations should help our faculty and students to make contributions and have impacts that they could not reasonably hope to achieve without collaborating. More generally, we must remember that our most fundamental interests are to make new contributions to research, to education, and to solving the great problems of the world and the puzzles of nature "that will best serve the nation and the world in the twenty-first century." And we should remember, too, that we stand for something even more fundamental – the core ideology of reason, rational and evidence-based debate, and the intellectual freedom to create and collaborate on which our entire academic enterprise rests.

I welcome your comments and suggestions. The expertise, good sense, and wisdom of the faculty will be of central importance as MIT seeks to manage its way through this complicated and challenging terrain.

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |