Varieties of Personal Information as Influences on

Attitudes Toward Surveillance

In The New Politics of Surveillance and Visibility, Kevin Haggerty and Richard Ericson, editors (University of Toronto Press, 2006). I am

grateful to them and to David Altheide, Albrecht Funk, Richard Leo, Glenn

Muschert, Jeff Ross and David Shulman and for helpful comments. An earlier

version was delivered at the meetings of the Society for the Study of Symbolic

Interaction, Tempe 2003.

Back to Main Page | Bibliography | Notes

By Gary T. Marx

For

it is a serious thing to have been watched.

We

all radiate something curiously intimate when

we

believe ourselves to be alone."

—E.M. Forster, Where Angels Fear to Tread

“You

ought to have some papers to show who

you are." The police officer

advised me.

"I

do not need any paper. I know who I

am," I said.

"Maybe

so. Other people are also

interested in knowing who you

are."

—B. Traven, The Death Ship

Social organization is increasingly based on technologies which, with laser-like focus and sponge-like absorbency, root out and give meaning to personal data. Fortunately there is now a growing literature looking at broad causes, forms, processes, policies and consequences of our move toward a surveillance society.1 In contrast, several decades ago emerging large scale computer systems drew only modest social science attention.

The majority of writers take it for granted that there is

trouble, as the Music Man warned, in

There are also technophiles, often nesting in engineering and computer science environments, who error on the other side, uncritically and optimistically welcoming the new surveillance amidst the challenges and risks of the 21st Century.

As a citizen concerned with calling public attention to the unequal playing fields of social control technology, whether involving undercover police and informing, computer matching and profiling, drug testing, electronic location and work monitoring or new communications, I have walked among the strident (see for example the articles on http://www.garymarx.net).

Yet as a social scientist partial to the interpretive approach and aware of the richness and complexity of social reality, I have done so reluctantly and role conflictually. In this paper I combine these interests in analyzing some of the structural roots of concern over surveillance involving personal information.

I seek an empirical, analytic, and moral ecology (or geography or mapping) of surveillance.2 Of particular interest are data which are involuntary collected and recorded, whether through intrusive and invasive methods —prying out what is normally withheld, or using technology to give meaning to what the individual offers (e.g., appearance, emissions unrecognized by the unaided senses, or behavior which traditionally was ignored, unrecorded and/or uncollated such as economic transactions, communication and geographical mobility). Also of interest are data gathered through deception or by unduly seductive or coercive (e.g., an offer you can’t refuse) methods. 3

Here I take the role of the somewhat disinterested outside observer, rather than the more interested subject –whether as surveillance agent or target. I seek to uncover the factors that help shape surveillance practices and our evaluation of them. I do this by identifying characteristics of the technologies, applications, goals, settings and data collected. This paper considers the last topic —the properties of the basic material surveillance technologies may gather.

I adopt a structural approach with caution, if not trepidation since as Hamlet claimed, “nothing’s either true or false but thinking makes it so”, (at least from the point of view of the beholder). Meaning lies not in the behavior, but in perception and interpretation.4 Yet rather than being idiosyncratic and random, the latter are largely context dependent. The challenge is to link the presence and evaluation of surveillance to the structural characteristics of the situation.

The best known normative perspective on this involves the Principles of Fair Information Practice developed in 1973 by the Health Education and Welfare Department (http://www.epic.org/privacy/code_fair_info.html ). These are very important, but not sufficient since they say little (or not enough) about the data collection itself including the means used and how they are applied, the goals sought, the setting and the kind of data collected. Nor do they adequately deals with issues of identification (including the move to merge distinct identifiers and to create a single identifier for each individual across settings), anonymity, pseudoanonymity and authentication.

At least five related analytic categories can be applied to the evaluation and practice of surveillance. The first involves the inherent characteristics of the means used (e.g., bodily invasive, extends the senses, covert, degree of validity)5. The second is the actual application of the means including the collection of the data and its subsequent treatment —is the procedure competently and fairly applied and once collected are trust and confidentiality sustained, is there adequate security, are undesirable consequences minimized or otherwise mediated? Traditional data protection principles primarily apply to the second part of this. A third factor considers the legitimacy and nature of the goals the surveillance tool is used for (e.g., for the protection of health as against voyeurism). A fourth factor involves the structure of the setting in which the surveillance is used (e.g., reciprocal vs. non-reciprocal, familial vs. non-familial). A final factor conditioning evaluations of surveillance is the actual content or the kind or form of data gathered –the subject of this article.

Kinds of Data

Beyond issues around means, goals and contexts there is the question of what type of data is involved. I emphasize content here, although the related issue of form with respect to the method of data collection and presentation is also briefly considered. What are the major kinds of data that surveillance may gather and what characteristics unite and separate them? When we speak of surveillance just what is it that is surveilled? What is surveillance information? How does the “what” condition evaluations of surveillance?

In the West we place particular emphasis on the sanctity of the borders around the person, the body, the family and the home and on the protection of information gathered in certain professional relationships such as those involving religion, health and law.

There is enormous variation in the morality and frequency of surveillance behaviors. At the extremes this is easy to see (e.g., contrast the discovery behavior of the Watergate burglars with that of lifeguards). Much domestic surveillance falls in a grayer area calling for a more fine grained analysis, but even at the extremes it is useful to be able to be more specific about why a form is acceptable or unacceptable.

We can push the seemingly self-evident and ask what broad cultural assumptions inform evaluations of the substance of surveillance, even while acknowledging that there will be local variation. Let us consider some questions illustrating the “kinds of data” issue.

With respect to form, under normal conditions presumably to be secretly video and audio taped is more revealing and a greater violation than either of those alone. But what if just one or the other was involved? Holding the kind of behavior constant (whether involving business, work, politics or social matters), is it a greater violation to be secretly video taped (with no audio) in a space presumed to be private, or to be audio taped with no video? How do these compare to a secret narrative account written up after-the-fact by a participant (infiltrator), or by an eavesdropper listening behind a door? What about comparing these when the recording is not secret?

Is it a greater invasion if (holding the permission issue apart) a video is shown to a medical class of a psychiatric interview in which the patient is anonymous, or is it a greater invasion if, instead, the class receives only a written narrative account, but in this case the patient is identified by name or other details? How does the presence or absence of various aspects of “identifiability” such as face, voice, name and composite details effect evaluations (e.g., face blocked but voice unaltered, face revealed but voice altered)? Why would these issues even be absent if this was an instructional video on the perfect form of a world class athlete?

Is there any difference between a camera on a public road noting only license plate numbers vs. one that in addition captures the image of the person in the car?

When purchasing something with cash, why does it seem inappropriate for a merchant to ask for home phone number? Why do some local merchants even refuse to accept calls with Caller-ID block? Why should information about my hobbies be requested when I seek a warranty for my toaster? How does unwarranted access to an unlisted phone number or home address compare to discovering a restricted email or postal box address? How does (or should?) the leaking of the fact that a CEO candidate was in a mental hospital differ from leaking of a report based on multiple biological and social indicators that the candidate has a high probability of developing heart disease within ten years?

In my junior high school student athletic performance was assessed by 10 measures. The top 10% received athletic letters and their scores were posted. Would it be appropriate to list all scores? Or consider contemporary cases in which schools have been prohibited from publicly listing the names of honor students.

On an airplane trip does it matter if the stranger sitting next to you is silent or instead begins asking you for, or revealing, personal information? Can the kind of unsolicited information offered or asked for by strangers be scaled from acceptable to unacceptable? What are the expectations here, even for close relationships? What tacit organizing principles are embedded? Contrast questions or revelations about sports teams or popular singers with that involving employment, politics, religion, family, sexual orientation and health.

Most of the above cases deal with taking information from the person but similar questions and latent patterning may be identified when unrequested information or stimulation comes to the person as well. For example contrast attitudes towards a sales appeal delivered by text (or orally) on a cell phone, over a land line phone, over a computer as spam, by regular mail and by a door to door salesperson? 6

With respect to content, what are the major kinds of

information that can be known about a person and how is the seeking and taking

of these evaluated by the culture? 7 As noted this is

distinct, if related to, the context and how the data are (and should and be)

treated according to policies such as the Principles of Fair Information

Practice) once collected and used.

It is difficult of course to talk about the meaning of personal information apart from its context (e.g., a discussion of political beliefs with a friends vs. with a feigned friend serving as a government informer, revealing social security number for employment vs. having it be required as a driver’s license number, or drug testing bus drivers as against all 7th graders who wish to participate in extra curricular activities).

Rather than seeing the personal or private as inherent properties, they are usefully seen in relation to particular persons, roles and contexts which may be fluid. Let us also differentiate empirical and normative meanings of private.

The word private has two meanings which often confuses discussion of these issues. Private can have an empirical meaning—referring to the actual state of knowledge about individual information. Unlike apparent age, gender, skin color etc. (aspects which are usually visible in face-to-face settings) or readily available information such as numbers in a telephone book, much information about the individual is not known by others (although as a defining element as we move from strangers to intimates the amount declines). Such information is “private” in being not known, rather than being “public”.

But beyond the actual condition of being known or unknown, private refers to privacy norms about the appropriateness of this empirical status. Is it right or wrong that various others have, or do not have information about the person?

We must ask private for whom and under what conditions? A doctor’s knowledge of a patient’s condition is information the patient shares. It ceases to be private as unknown to the doctor even though that knowing does not obviate the doctor’s obligation to treat it confidentially. Knowledge that one’s partner has a tattoo in places not usually warmed by the sun is different from that knowledge obtained by an unknown voyeur with a hidden camera.

In objectifying and treating types of information more abstractly as I do in this paper, it is vital not to lose sight of the centrality of the empirical settings. However granted the centrality of situational or contextual matters to the topic, some conceptual mileage still lies in considering the “objective” attributes of various kinds of information about persons. This can be seen by holding the context constant and imagining different kinds of information. Thus as part of treatment a doctor may know that a patient is HIV positive, has arthritis, no religious preference, is a vegetarian and a Chicago Cubs fan. Merely because the doctor is aware of the above does not mean that the kinds of information have become equivalent. Losing (or giving up) control of information does not make it impersonal or eliminate the normative aspects. 8

All private (in either sense noted above) information about an individual is in one sense personal, but all personal information does not involve expectations of privacy, nor when it does is this to the same degree. Within contexts it is possible to make comparative statements across kinds of information and information may retain its normative status, regardless of whether or not it is known.

There is no easy answer to the question “what is personal

information?” or to how it connects to perceived assaults on our sense of

dignity, respect for the individual, privacy, and intimacy. However even giving

due consideration to the contextual basis of meaning and avoiding the shoals of

relativism as well as reification, it is possible to talk of information as

being more or less personal. There is a cultural patterning to behaviors and

judgements about kinds of personal information.9

Types of Information

on the Embodied

Surveillance involving information that is at the core of

the individual and more “personal” is likely to be seen as more damaging than

that involving more superficial matters.10

But what is that core and what radiates from it? How does the kind of

information involved connect to that core?

Scientific explanation and moral evaluation require

understanding what personal information is and how assessments of its

collection, representation and communication vary. This discussion is organized

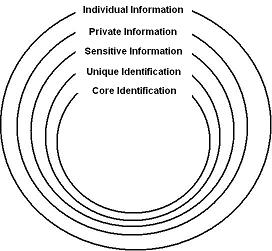

around the concepts in tables 1-3. The concentric circles in Table 1 show

information that is individual, private, and intimate and sensitive with a unique core identity at the center. Table 2

describes kinds of information that may be gathered. Table 3, builds on this.

It is more analytic and identifies cross-cutting dimensions that can be used to

unite seemingly diverse, or to separate seemingly similar, forms. This permits

more systematic comparisons and some conclusions about how the nature of the

information gathered by surveillance is likely to be viewed.

Given the complex, varied and changing nature of the realities we seek to understand, I approach the task of classification humbly and tentatively and note some limitations. 11

The concepts are not mutually exclusive. A given type of information about the person can fit in more than one category —either because the concepts deal with different aspects such as the body, time, place, relationships or behavior, or because the information has mixed elements. For example, voice print, handwriting and gait analysis are biometric and behavioral in contrast to a form such as DNA, which is entirely biometric.

My emphasis is on offering a framework that usefully

captures the major kinds of personal information the technologies gather and

create, rather than on a fully logical, operationally defined system which can

come later.

Information About Persons

What is personal information? One approach defines it in property terms as any information which the individual has certain decisional rights over.12 Thus facial image, copyrighted material or the contents of one’s medicine cabinet are personal –partly because they “belong” to the individual. However, a control definition is limited in that once control has been given up, personal information is still present.

Thus in the discarding of a pill container or a magazine

subscribed to personal information usually remains. In public settings others

may generally record the image and sounds the individual gives off.13 These do not cease to reflect the person as a

result, even if they are re-creations and not “really” the person. 14 Or consider a

person’s DNA obtained from dental floss discarded as garbage. A

Another issue raising unresolved control questions is telephone number. This became clear in the controversies over Caller-Id. The act of paying for phone service (and paying even more for an unlisted number) would seem to imply control over the number. Yet as legislation and regulations generally imply, the phone number is rented and “belongs” to the phone company (at least that is the case for land lines). 17 The question of formal ownership is distinct from the conditions of use and whether the number can be released if the phone company so chooses.18 However its potential for reaching the individual and for probabilistic geo-demographic analysis brings a personal component to it.

As the above cases suggest control is an important dimension with policy implications. 19 Yet something beyond control or possession is involved in defining personal information. We need a broader conception.

Another approach is to view any datum attached to a corporeal individual (identified by distinguishing characteristics of varying degrees of specificity) as “personal” because it corresponds to a person (e.g., being identified as a citizen of the United States, a watcher of the Superbowl, middle-aged or owner of a SUV). But information about an individual is not necessarily equivalent to personal information in a more restricted sense.

Knowledge about the kind of car one drives when millions of

people drive a similar car is a pale form of “personal” information. It is more

like impersonal information, although at a general level it serves to

differentiate owners from non-owners and may convey symbolic meaning (e.g., whether one owns a red convertible

sports car or a black mega-pickup truck with flames painted on the front may be

seen to be making a statement, whether intended or not, about the owner.)

When we refuse or resent, having information about ourselves taken, it is often because it is seen as “personal” or “none of your business”. 20 Here something additional is present beyond many of the kinds of general information that can be associated with an individual. Private personal information needs to be located within the larger category of individual information.

Even within the more limited category, all private information (defined as information that is not automatically known about the other which is subject to the actor’s discretion to reveal it or give permission for it to be revealed) is not the same. Some goes to the very center of one’s person while other information is peripheral or trivial (e.g. sexual preference vs. city of birth).

Considerations of the private and personal involve both a content and a procedures piece here.21 I emphasize the former.

TABLE 1:

Concentric Circles of Information

We can think of information about persons as involving concentric circles of individual, private, and intimate and sensitive information.

(Table 1.) The outermost circle is that of individual information which includes any data/category which can be attached to a person. The individual need not be personally known, nor known by name and location by those attaching the data. Individuals need not be aware of the data linked to their person.

Individual information varies from that which is relatively impersonal with minimal implications for an individual’s uniqueness, such as being labeled as living in a flood zone or owning a four door car, to that which is more personal such as illness, sexual preference, religious beliefs, facial image, address, legal name and ancestry. The latter information has clearer implications for selfhood and for distinctly reflecting the individual.

The information may be provided by, or taken directly from the person (e.g., remote health sensors or a black box documenting driving behavior). Or it can be imposed onto persons by outsiders as with the statistical risk categories of a composite nature used in extending credit.

The next circle refers to private information not automatically available, absent special circumstances to compel disclosure as with social security number for tax purposes or a subpoena or warrant for a search, such information is defined by discretionary norms regarding revelation. An unlisted phone or credit card number and non-obvious or non-visible biographical and biological details (“private parts” 22) are examples. We can refer to information about the person not known by others whose communication the individual can control as existentially private.

In contrast to such personal information of which the

individual is aware is that with implications for life chances imposed from the

outside of which the individual is often unaware. Much organizational categorization of individuals of the kind

Foucault first called attention to is encompassing, routine and invisible to

the subject and (artifactual). 23 This social

sorting is fundmental to current social organization (Lyon 2002 ; Bowker and

Star 1999). Labeling by judicial, mental

health or commercial organizations may involve imputed identities (e.g., a

recidivism risk category) of which the individual is unaware (whether of the

existence of the information or its’ content). Such imposed classifications are

better seen as secret than private. The information may be considered personal

and even sensitive were it known by the individual.

Another distinction is whether, once known, an

organization’s information corresponds to how persons see themselves. This

raises fascinating questions involving the politics of labeling and measurement

validity and can extend even beyond the grave. 24

The disparity between technical labeling and self-definition may increase and

become more contested as abstract measurements claiming to characterize the

person and predict future behavior based on comparisons to large data bases

become more prominent. 25

Even when there is no disparity such labeling serves as a new source of identity e.g, as a high SAT scorer or a low cholesterol person. Organizational labeling has also become a marketeable commodity –among many other forms note the selling of background and credit rating scores at Sam’s Club stores. 26

The next circle is that of intimate and/or sensitive information.

Intimate comes from the Latin intimus, meaning inmost. Used as a verb the word intimate means to state or make known, implying that the information is not routinely known. Several forms can be noted.

Some “very personal” attitudes, conditions and behaviors take their significance from the fact that they are a kind of currency of intimacy selectively revealed, only to those we trust and feel close to. Such personal information is not usually willingly offered to outsiders, excluding the behavior of exhibitionists and those seen to be lacking in manners. The point is not that the behavior that might be observed is personal in the sense of necessarily being unique (e.g., sexual relations), but that control over access affirms respect for the person and sustains the value of intimacy and the relationship. Persons who prematurely reveal their hole cards or private parts are likely to do poorly at both cards and love.

We can also differentiate an intimate relationship from

certain forms of information or behavior which can be intimate independent of

interaction with others. E.M. Forster captures this in noting that we,

“radiate something curiously intimate

when we believe ourselves to be alone". This suggests a related form

–protection from intrusions into solitude or apartness. Whether alone or with

trusted others, this implies a sense of security, of not being vulnerable, of

being able to let one’s guard down which may permit both feelings of safety and

of being able to be “one’s self”. 27

This apartness when protected by physical structures and manners (e.g. the case of bathroom activities) from others’ observation, generally protects not against strategic disadvantage or stigmatization, but rather sustains respect for personhood.

The privacy tort remedy of intrusion attempts to deal with the subjective and emotional aspects of harm from incursions into solitude when personal borders and space are wrongly crossed.

These are harder to define than a harm such as unauthorized

commercial use of a person’s data, reporting them in a false light or reporting

private facts. The former involve actions taken by the other after possession

of information and usually some type of publication, even if no more than a

sign in a shop window. In contrast with intrusion, it is the process itself

which is objectionable.

Consider also moments of vulnerability and embarrassment observable in public. For example, the expression of sadness in the face of tragedy –as with a mother who has just lost a child in a car accident. Here manners and decency require disavowing, looking the other way, not starring, let alone taking and publishing a news photo of the individual’s grief.

Some information is “sensitive,” implying a different rationale on the actor’s part for information control and the need for greater legal protections. This includes strategic information that could be useful for an opponent in a conflict situation or a victimizer, 28 or a stigma that would devalue individuals in other’s eyes, or subject them to discrimination.

Various

More broadly a central theme of Erving Goffman’s work is that the individual in playing a role and in angling for advantage presents a self to the outside world that may be at odds with what the individual actually feels, believes or “is” in some objective sense. Through manners and laws, for most purposes, modern society acknowledges the legitimacy of there being a person behind the mask.

Unique and Core Identity

Two final circles at the center involve a person with

various identity pegs. These (whether considered jointly or individually)

engender a unique identity (“only you” as the song says) in being attached to

what Goffman refers to as an “embodied” individual who is usually assumed to be

alive, but need no longer be. Knowing unique identity, answers the basic

question raised by

The elements that make up the individual’s uniqueness are

more personal than those that don’t and as degree of distinctiveness increases

so does the “personalness” of the information.

Traditionally, unique identity tended to be synonymous with a core identity based on biological ancestry and family embedment. Excluding physically joined twins, each individual is unique in being the off-spring of particular biological parents, with birth at a particular place and time.

Parents and place of birth of course may be shared. Yet even for identical twins, if we add time of birth to the equation, the laws of physics and biology generate a unique core identity in the conjunction of parents, place and time of birth. This may of course be muddied by unknown sperm and egg donors, abandonment and adoption.

For most persons throughout most of history discovering identity was not an issue. In small scale societies, where there was little geographical or social mobility and people were rooted in very local networks of family and kin, individuals tended to be personally known. Physical and cultural appearance and location answered the “who is it?” question.

Names may have offered additional information about the

person’s relationships, occupation, or residence (e.g., Josephson, Carpenter,

However the literal information offered by a name is of little use when the observer, neither personally knowing, nor knowing about the individual in question, needs to verify the link between the name offered and the person claiming it.

With large scale societies and the increased mobility associated with urbanization and industrialization core identity came to be determined by full name and reliance on proxy forms such as a birth certificate, passport, national identity card and driver’s license. (Caplan and Torpey, 2001).

Yet given adoption of children, the ease of legally changing

or using fraudulent names in the

The conventional paper forms of identification have been supplemented by forms more inherent in the physical person, though even here we must remember that the measurement offers a representation of something inherent and this reflects choices rather than anything “given” in nature.

Such measurements and transformations are a form of simulacrum. (Baudrillard, 1996; Bogard 1996) According to the dictionary this can be a neutral “image of something” as well as a darker “shadowy likeness”, “deceptive substitute” or “mere pretense”. Among the meanings of simulate are both “imitate” and “counterfeit”. That contrast of course is what the fuss is all about, just how far in distorting the richness of the empirical should a simulation or a symbol go before it is rejected as invalid, inauthentic, inefficient or ineffective?

With the expansion of biometric technology a variety of indicators presumed to be unique (and harder to fake) are increasingly used (e.g., beyond improved fingerprinting, we see identification efforts based on DNA, voice, retina, iris, wrist veins, hand geometry, facial appearance, scent and even gait). The ease of involuntarily and even secretly gathering many of these may increase their appeal to control agents who need no longer deal with the messy issues of informed consent.

Validity varies significantly here from very high for DNA and fingerprinting (if done properly) to relatively low for facial recognition. There also are many ways of thwarting the surveillance. Even when validity is not an issue biological indicators are not automatic reflections of core identity, although they may offer advantages such as being ever present and never forgotten, lost or stolen. To be used for identification there must be a record of a previously identified person to to match the indicator to. 31 These need not lead to literal identification, but rather whether or not the material presumed to reflect a unique person is the same as that in a data base to which it is compared (i.e., “is this the same person?” whomever it is).

Police files are filled with DNA and fingerprint data that are not connected to a core legal identity. 32 With data from multiple events, because of matching, police may know that the same person is responsible for crimes but not know who the person is.

The question, “who is it?” may be answered in a variety of other ways that need not trace back to a biologically defined ancestral core or legal name. For many contemporary settings what matters is determining the presence of attributes warranting a certain kind of treatment, continuity of identity (is this the same person) or being able to locate the individual, not who the person “really” is as conventionally defined.

A central policy question is how much and what kind of

identity information is necessary in various contexts. In particular, whether identification of a unique person is appropriate and,

if it is, what form it should take.

Thus far we have noted ancestral, legal name and biometric

forms of identity. Let us also consider locational identity, pseudonyms and

anonyms. Table 2 lists 9 broad types of descriptive information commonly

connectable to individuals.

TABLE 2

Some Types of Descriptive Information Connectable to

Individuals

| 1. Individual identification [the who question] | ||

|

Ancestry Legal

name

Alpha-Numeric

Biometric

(natural, environmental)

Password

Aliases,

nicknames Performance |

||

| 2. Shared identification [the typification-profiling question] | ||

|

Gender Race/ethnicity/religion Age Education Occupation Employment Wealth DNA

(most) General

physical characteristics (gender, blood type, height, skin and hair color)

and

appearance

Health status Organizational

memberships Folk

characterizations by reputation –liar, cheat, brave, strong, |

||

| 3. Geographical/Locational [the where, where from/where to and beyond geography, how to reach question] | ||

| A. Fixed | ||

|

Residence,

residence history Telephone

number (land line) Mail

address Cable TV |

||

| B. Mobile | ||

|

Email

address Cell

phone Vehicle

and personal locators Wireless

computing Satellites Travel records |

||

| 4. Temporal [the when question] | ||

|

Date and time of activity |

||

| 5. Networks and relationships [the who else question] | ||

|

Family

members, married or divorced Others

the individual interacts/communicates with, roommates,

at

a given location (including in cyberspace) or activity

including neighbors |

||

| 6. Objects [the which one and whose is it question] | ||

|

Vehicles Weapons Animals Communications

device Contraband Land, buildings and businesses |

||

| 7. Behavioral [the what happened/is happening question] | ||

|

|

A. Communication |

|

|

|

Fact of using a given means (computer, phone, cable tv,diary, notes or library) to create, send, or receive information (mail covers, subscription lists, pen registers, email headers, cell phone, GPS) Content

of that communication (eavesdropping, spyware, library use, book

purchases) |

|

|

B. Economic behavior --buying (including consumption patterns and preferences), selling, bank, credit card transactions |

||

|

C. Work monitoring |

||

|

D. Employment history |

||

|

E.

Norm and conflict related behavior --bankruptcies, tax liens, records, suits filed |

||

|

8.

Beliefs, attitudes, emotions [the

inner or backstage and presumed |

||

|

9. Measurement Characterizations (past, present, predictions, potentials [the kind of person, predict your future question] |

||

|

Credit

ratings and limits Insurance

ratings SAT

and college acceptability scores Intelligence

tests Civil

service scores Drug tests Truth

telling (honesty tests, lie detection) Psychological

inventories, tests and profiles Occupational

placement and performance tests Medical (HIV, genetic, cholesterol etc.) |

||

| 10. Media references (yearbooks, newsletters, newspapers, tv, internet) | ||

Location refers to a person’s “address”. It answers a "where", more than a "who" question. Address can be geographically fixed as with most residences and workplaces, land line phones and post office boxes. A person of interest may, or may not be at these places or be using a device. Yet such addresses are a kind of tether from which persons usually venture forth and return.

In contrast are geographically mobile (if always located somewhere) addresses, as with a cell phone, email, or implanted GPS chip. These portable means need not reside or remain in a fixed place and stand in a different relationship to the person than a fixed geographical address which is believed to offer greater accountabililty. 33

Two meanings of address are “reachability” involving an

electronic or other communications address and the actual geographical location

in latitude and longitude of the person in question at that time. These may,

but need not be linked34, nor do they

require core id. Recent developments in the rationalization of

Distance mediated and remote forms of cyber-space

interaction are ever more common, and the ability to reach and be reached is

central for many activities. This

ability to locate postal and conventional phone addresses is now matched by the

ability to locate mobile cell phone users.

Communication location is increasingly important (beyond whatever additional knowledge it might contain e.g., an address in Harlem or Beverly Hills, a phone number spelling a name or as evidence indicating a person was or was not at a given place). For many purposes being able to “reach” someone becomes as or more important than knowing “where” they literally are geographically. The “locator” number for bureaucratic records is related, however it connects to the file, not to the person.

The "where" question need not be linked with the

"who" question. The ability to communicate (especially remotely) may

not require knowing who it “really” is, only that they be accessible and

assessable. Knowing location may permit taking various forms of action such as

communicating, blocking, granting or denying access, penalizing, 35 rewarding,

delivering, picking up or apprehending.

The “who” may also be known and the “where” unknown. For

example the identity of fugitives is known but not how they can be reached. Even knowing both name and location an

individual may be unreachable, as when blocking is present, or there is no

extradition treaty. For example the

Nor need the specific identity be known in order to take broad actions based on categorical/group inferred attributes. As the slogan “you are where you live”, suggests the “where” question for many purposes is a statistical proxy for the “who” question. This has implications for trying to shape behavior through appeals and advertisements, environmental engineering, setting prices (such as for insurance) and the location of goods and services. Claritas’ location data offers customers “segmentation, market research, customer logistics and site selection”.

Such typification based on statistical averages is increasingly a cornerstone of organizational decision making for merchants, employers, medical doctors, police and corrections agents. From a standpoint of presumed rationality and efficiency it is understandable. But actions at the aggregate or group level, however logical, may clash with expectations of individualized treatment. Our sense of fairness involves assumptions about being treated in a way that is personal in reflecting the individual’s particular circumstances. There is contradiction or irony here in that in order to have such fine grained treatment vast amounts of personal information are required, creating a potential and temptation to treat individuals in general terms.

In reducing the several hundred thousand census blocks to a limited number of geodemographic types Claritas tells us that, “people with similar lifestyles tend to live near one another.” One of its’ “products” —PRIZM “describes every U.S. neighborhood in terms of 62 distinct life style types, called clusters, while its’ MicroVision “defines 48 lifestyle types called segments” (www.claritas.com .) Such characterizations combine census, zip code, survey and purchase data. You are what you consume. For many marketing purposes there is no need to know core identity if fixed or mobile location is known. The latter has received a very large boost with the appearance of the 911E system which federal law now requires in response to the rapid spread of cell phones not tied to a fixed residence.

Location information has a very special status in that it can both identify and monitor or track movement over time. In addition it offers the potential to both take from and to impose upon the borders of the person. As with monitoring of internet behavior and subsequent ads, it can sequentially join two forms of personal border crossing.

This contrasts with most other kinds of personal information collection (e.g., a photograph, a name, a medical record, or an overheard conversation) which only involve taking from the person. Location information in a sense offers two for one. The substantive information it provides can be compared to predictive models (or used to build them) that then serve to direct how the individual is responded to. In that regard it is like a supermarket saver card. But it additionally offers a means of action –knowing where the person may permit “reaching” them, either literally as with 911 responders or through targeted communications.

Pseudonyms and Anonyms

Apart from legal name and location, 36

unique or at least somewhat distinctive identification may involve pseudonyms

such as a nickname, alias, pen name, nom

de plume or nom de guerre.

Alpha-numeric indicators are functionally equivalent to a pseudonym. A numeric or alphabetic identification is often intended to refer to only one individual. While names can be held in common, letters and numbers are sufficient as unique identifiers, although they may also be keys to additional common information, such as where and when issued, and a rating. Unlike birth parents or DNA material, they are merely convenient and need have no intrinsic link to core identity.

As buffering devices, pseudonyms may offer a compromise solution in which protection is given to literal identity or location, while meeting needs for some degree of identification, often involving continuity of identity. They vary in the degree of pseudo-anonymity they offer. Whether intentionally or unintentionally, they often may be linked back to an individual known by name, location or other details.

The number on a secret Swiss bank account permits

transactions while keeping the owner’s identity unknown to outsiders. An

on-line service such as AOL likely knows the true (or at least claimed)

identity of its customers, even as they

are permitted to have 5 pseudonyms for use in chat rooms and on bulletin

boards. The nom de plume of authors wishing to shield their actual identity

will usually be known to their publisher. The true identity of protected

witnesses, spies and undercover operatives, when not using their real names, is

known by the sponsoring agency. License plate number also fits here. The

identity of the owner is no longer publicly available, even though it is known

by the state and can be made available under appropriate conditions. 37

There are also time-lagged forms such as census records, sealed court and arrest records and other government documents which protect identity and content for a fixed period of time and are then made available.

In other forms an organization may be explicit in offering confidentiality. Persons calling tip hot lines may be given an identifying number which they may latter use to collect a reward. Those engaged in illegal activities, leakers, whistle blowers and the stigmatized may be offered full anonymity. For example persons encouraged to return contraband during a grace period are told, “no questions asked.” In some areas, the name of those tested for AIDS is not requested and they are identified only by a number. 38

There are many settings where anonymity and the absence of a documentary record are implied, at least in the sense that individuals are not asked for personal information. Barter and cash purchases, many kinds of information request and being in a public place are traditional examples.

In other settings, the core identity of the person is deemed irrelevant, even though some information and continuity of identity (apart from literally knowing it) is required. Many contexts require that the individual have some general characteristics warranting inclusion or exclusion, access or its’ denial, or a particular kind of treatment.

Eligibility certificates (or tokens) offer a way of showing that one is entitled to a given service without requiring that the user be otherwise identified. Theater tickets and stamps on the hand at concerts, or cards purchased with cash for using telephones, computers, photo-copy machines, mass transit and EZ pass transmitters for toll roads are examples. With smart card technologies such forms are likely to become much more common.

While possibly offering some information such as where and when obtained and where used, such certificates do not indicate who obtained or used them (although a hidden video camera may reveal that). Tokens offer a way of having accountability –e.g., proof of eligibility, while otherwise protecting personal information.

Beyond these certifications other forms of shared, but not uniquely personal information, can be seen in the possession of artifacts and knowledge or skill demonstration. Thus uniforms, badges, and group tattoos (and other visible symbols such as a scarlet letter or cross) are means of identity. These represent their possessor as a certain kind of person whether involving eligibility or presumed social and moral character, with no necessary reference to anything more. The symbols can of course be highly differentiated with respect to categories of person and levels of eligibility. But the central point is their categorical rather than individual nature.

The possession of knowledge can also serve this function (e.g., knowing a secret hand signal, a pin or account number, or a code or the “color of the day“ (used by police departments to permit officers in civilian clothes to let uniformed officers know they are also police). Demonstrating a skill, such as passing a swim test in order to be in the deep end, can also be seen as a form of identity-certification.

When no aspects of identity are available (being

uncollected, altered, or severed) we have true anonymity. With respect to

communication, a variety of forwarding services market anonymity. Consider a

call forwarding service that emerged to thwart Caller-Id. The call, after being

billed to a credit card was routed through a 900 number and the originating

phone number is destroyed. Calls from pay phones also offer anonymity not

available from a home telephone. There are various mail forwarding services and

anonymizing/anomizer web services that strip (and destroy) the original

identifying header information from an e-mail and then forward it. 39

Among the dictionary meanings of anonymity are “unknown

name,” “unknown authorship,” and “without character, featureless, impersonal”. The traditional meanings of the term are

somewhat undercut by contemporary behavior and technologies. In writing of the

“surveillant assemblage” Haggerty and

Erickson (2000) note “the progressive ‘disappearance of disappearance’” as once

discrete surveilance systems are joined. Genuine anonymity appears to be less

common than in the past. The line between pseudo-anonymity and anonymity is more

difficult to draw today than it was for the 19th and much of the 20th

centuries. More common are various forms of partial anonymity.

“Anonymous” persons may send or leave a variety of clues

about aspects of themselves (apart from name and location) as a result of the

ability of technology to give meaning to the unseen, unrecognized and seemingly

meaningless. Consider a DNA sample from a sealed envelope or a straw used in a

soft drink, heat sensors that “see” through walls and in the dark, software for

analyzing handwriting and writing patterns, face and vehicle recognition

technology, the capture of computer id and sections of a web page visited and

composite profiles. Anonymity ain’t what it used to be—whatever the intention

of the actor wishing to remain unrecognized and featureless.

Patterns and Culture

Social leakage, patterned behavior and a shared culture are other reasons why it is relatively rare that an individual about whom at least something is known will be totally “without character” or “featureless”.

Some identification may be made by reference to distinctive appearance, behavior or location patterns of persons. Being unnamed is not necessarily the same as being unknown. Some information is always evident in face-to-face interaction because we are all ambulatory autobiographies continuously and unavoidably emitting data for other's senses and machines. The uncontrollable communication of some data is a condition of physical and social existence. This varies from information the individual is aware of offering such as appearance or when using a cell phone, to that which he or she is likely to be unaware of such as scent, gait, radiation and brain waves, hidden identification symbols on property such as cars and documents (whether in the paper or left by a copy machine), and the subtle inferences available to various types of identification specialists, whether medical or juridical.

It may also involve leakage which the individual would like to control, but will often be unable to, such as facial expressions when lying (Eckman 1985, 2003) or sudden surprise as with unexpectedly seeing a police officer. New technologies have greatly expanded the potential to turn leaky data into information.

A distinction Erving Goffman makes between knowing a person in the sense of being acquainted with them, and knowing of them, applies here. The patterned conditions of urban life mean that we identify many persons we don't "know" (that is we know neither their names, nor do we know them personally). Instead we know some form of their social signature—whether it is face, a voice heard over mass media or phone, a location they are associated with, or some distinctive element of style. In everyday encounters, for example, as with regularly using public transportation we may come to "know" other riders in the sense of recognizing them.

Style issues fit here. Skilled graffiti writers may become well known by their "tags" (signed nicknames) or just their distinctive style, even as their real identity is unknown to most persons. (Ferrell 1996) Persons making anonymous postings to a computer bulletin board may come to be "known" by others because of the content, tone or style of their communications.

Similarly detectives attribute re-occurring crimes with a distinctive pattern involving time, place victim and means of violation to a given individual, even though they don't know the person's name (e.g., the Unabomber, the Son of Sam, the Red Light Bandit, Jack-the-Ripper).

With the development of systematic criminal personality profiling detectives, steeped in the facts of previous crimes, make predictions about the characteristics and behavior of unidentified suspects. Using general cultural knowledge, research data, data from other cases, facts from the crime scene, along with intuition and the ability to imagine how the other thinks and feels (“verstehen”), they develop profiles that are intended to help understand and apprehend perpetrators. (e.g., Douglas, 1992, Ressler, 1992). They claim to “know” persons without literally knowing them with respect to core identity. 40

There are also pro-social examples such as anonymous

donors whose gift is distinctive (“in

memory of Rosebud”) or who give in predictable ways which makes them

"known" to charities. They differ from the anonymous donor who gives

only once in an indistinct fashion.

Style of course is often linked with identity—a marketing

goal sought by celebrities and advertizers relying on public recognition. This

varies from seeing a painting and knowing it is a Van Gogh, to the ability to

identify popular singers. In such cases for those in the know, style and identity

are merged. One kind of specialization is the ability to read clues others

offer. 41

Composite Identity

Identification may involve social categorization. Many visible forms do not differentiate the individual from others sharing them (e.g., gender, age, skin color, disability, linguistic patterns, and general appearance). Inferences about others such as education, class, sexual orientation, religion, occupation, organizational memberships, employment, leisure activities and friendship patterns are often volunteered or easily discovered.

Dress or simply being at certain places at particular times or associating with particular kinds of people can also be keys to presumed aspects of identity (e.g., at a gay bar or with political dissidents). Folk wisdom show this profiling logic in claiming, "birds of a feather flock together" or "you are known by the company you keep".

Attributes which are common and readily available to others are not usually thought of as being private matters, although manners may require tactfully disattending, and anti-discrimination legislation formally ignoring, what is obvious.

The compartmentalization (isolation from each other) of various aspects of the person passively protect the individual’s privacy and uniqueness. Any given general attribute may reveal little —such as being male or living in a rural area. However when an increasing number of categories are combined, the individual may be uniquely (or almost) identified through a composite identity.42 Privacy may be invaded and a distinctive personal mosaic created with the merging of a number of seemingly non-personal general items (gender, ethnicity, age, education, occupation, census district). The greater the number of categories involved, the more specific the information and thus, other factors being equal, the closer to the unique individual and the more personal or at least one major meaning of it. 43

David Shulman (1994) observes that the skill or art of the

detective (whether public or private) is to use readily accessible individual

information, (available partly because it tends to be neutral,

non-controversial or non-discrediting) to locate hidden and discrediting

sensitive information.

Traditionally personal information such as social security, telephone and license plate number or birth date were viewed as substantively neutral (in contrast to information regarding HIV status or a criminal record).44 Relatively little attention was given to keeping the above numbers and the personal information they are linked to private.

Yet with linked computerrecords (whether involving a single idntifier or merging of multiple identifiers) they take on a more personal meaning. As locators they can be used to learn about and find or reach the person, going from the public-neutral to private-discrediting information, generating a mosaic image of the person through linking previously unconnected information, and generating predictions based on comparing the person’s data to that of similar others about whom much more is known.

Cultural Knowledge

Even having only one or two pieces of information may be revealing when there is general cultural knowledge. Here visibility refers not to what we literally see, but to what we know (or can discover) as participants in the culture. Sherlock Holmes’ success for example lay partly in his ability to deduce applicable facts from his broad knowledge of culture and society. He often used his general knowledge to understand and locate a culprit.

There is a great line in the film Annie Hall in which Woody

Allen, on learning that a young women he meets is from

She is reacting against Allen’s categorization not surveillance per se –as might be the case if she discovered he was eavesdropping. The reaction against such labeling involves the assertion of individualism against the predictable commonalties presumed by culture and roles. 46 In the tradition of Sartre “authenticity” involves refusing to accept societal labels, particularly when they are stigmatizing. Freedom exists in rejection of the expectations and positions offered by the culture. Sartre and implicitly, if more ambivalently, for Goffman with his concept of role distance, there is a moral obligation to resist.

Broad knowledge of a culture, whether through socialization

into it, or simply becoming familiar with it, may offer information about an

individual whom nothing specific is known. To know that an “anonymous”

individual is a citizen of the

This ability to go from generalized knowledge to assumptions

about unknown individuals is a cornerstone not only of detectives, but also of

marketing research and of social research based on samples more broadly. In the

latter cases, what is learned from a carefully chosen sample of persons with

particular demographic characteristics (e.g., urban, college educated, males

between 18-25), who are paid to volunteer information about themselves, also

reveals information about others with those characteristics. Those in the

sample are presumed to speak for, and be representative of, their group.48 There is an

unrecognized value conflict here between the individual who, in consenting also

in a sense “consents” for others who are not asked.

Form

The form and elements of the content of personal information are connected, at least initially, e.g., (video lens gathers the visual). But the tool and the resulting data can be subsequently disconnected in the presentation of results. Video 49 or audio recordings are likely to be most powerful and convincing if directly communicated the way they were recorded. 50 However their information can also be communicated in other ways—a written narrative of events or a transcript of conversations. Conversely observations and written accounts can be offered as visual images –as with a sketch of a suspect or a video reconstruction of a traffic accident for court presentation.

Many new surveillance forms are characterized by some form

of conversion from data collection to presentation. Thus physical DNA material

or olifactory molecules are converted to numerical indicators which are then

represented visually and via a statistical probability. With thermal imaging

the amount of heat is shown in color diagrams sometimes suggestive of objects.

The polygraph converts physical responses to numbers and then to images in the

form of charts. Satellite images convert varying degrees of light to computer

code which are then offered as photographs. Faces and the contours of body

areas can be blocked or otherwise distorted when the goal is not

identification, but searching for contraband rather than identification.

When not presented with intent to deceive, the visual and audio, in conveying information more naturalistically (even if still once or more removed in involving conversion from the raw data to what is offered the observer), seem more invasive than a more abstract written narrative account or numerical and other representations relying on symbols. 51

The visual in turn is more invasive than the audio. The

Chinese expression “a picture is worth a thousand words” captures this,

although it must be tempered with some skepticism about whether, “seeing is

believing”. Direct visual and audio data implicitly involve a self-confessional

mode which initially at least, enhances

validity relative to a narrative account of a third party, or even a written

confession after the fact by the subject. Such data create the illusion of

reality.

The other senses such as taste, smell and touch play a minimal role, although they may be used to bring other means into play, as with justifying a visual search on the basis of smelling alcohol or drugs. Although the senses may not be as independent as is usually assumed. Recent research in neurology suggests the senses are interconnected and interactive and can not be as easily separated as common sense would suggest. 52

Assessing Surveillance Data

Let us move from the descriptive categories of information in table 2 to the dimensions in table 3 which can be used to compare and contrast the former. This permits some conclusions with respect to how the kind and form of data relate to the prevalence and assessments of surveillance. The dimensions should be seen on a continuum, although only the extreme values are shown.

The multi-dimensional nature of personal information, the extensive contextual and situational variation related to this and the dynamic nature of contested social situations prevents reaching any simple conclusions about how the information gathered by surveillance will (empirically) and should (morally) be evaluated. Such complexity may serve us well when it introduces humility and qualification, but not if it immobilizes. Real analysts see the contingent as a challenge to offer contingent statements.

In that spirit I hypothesize that other factors being equal, attitudes toward surveillance will be more negative the more the values on the left side of Table 3 are present. 53 These combine in a variety of ways. They might also be ranked relative to each other –the seriousness of a perceived violation seems greatest for items 1-9. But such fine-tuning is a task best left for future hypothesizing.

Now let us simply note that there is an additive effect and the more (both in terms of the greater the number and the greater the degree) the values on the left side of the table are present, the greater the perceived wrong in the collection of personal information. The worst possible cases involve a core identity, a locatable person, and information that is personal, private, intimate, sensitive, stigmatizing, strategically valuable, extensive, biological, naturalistic54 and predictive55 and reveals deception 56, is attached to the person, and involves an enduring and unalterable documentary record.

The sense of indignation of course deepens when other elements are considered (e.g., invalid, inappropriately applied or irrelevant means, lack of consent or even awareness on subject’s part, illegitimate goal). But my point here is to hold those constant and ask what conceptual mileage might lie in just considering what it is that is surveilled.

It is one thing to list characteristics of results likely to be associated with attitudes toward

surveillance and the perception of normative violations. However proof and

explanation are a different matter. The assertions drawn from Table 3 are

hypotheses to be empirically assessed. 57

Next, if this patterning of indignation (or conversely acceptance) of the stuff

of surveillance is accurate what might account for it? Is there a common thread

or threads traversing these? Several of

the most salient can be noted.

For things not naturally known, norms tend to protect against inappropriately revealing information reflecting negatively on a person’s moral status and strategic interests (e.g., employment, insurance, safety, non-discrimination). The policy debate is about when it is legitimate to reveal and conceal (e.g., criminal records after a sentence has been served, unpopular or risky, but legal life styles, contraceptive decisions for teenagers, genetic data to employers or insurers, credit card data to third parties). It is also about the extent to which the information put forth may be authenticated, often with the ironic additional crossing of personal borders.

Another distinct factor is the extent to which the

information is unique, characterizing only one locatable person, or a small

number of persons. Protection of information that would lead to unique and even

core identity is more a means to the factors in the preceding paragraph than an

end in itself. This is one version of

the idea of safety in numbers, although the anonymity and lack of

accountability may ironically lead to

anti- or un-social behavior.58

Also more in the means category, and set apart from immediate instrumental consequences, are norms that sustain respect for the person in protecting zones of intimacy, whether the insulated conversations and behavior of friends; actions taken when alone; or the physical borders of the body. The protection of these informational borders symbolically and practically sustains individual autonomy and liberty. Backstage behavior can also be a resource in which strategic actions are prepared.

This paper has analyzed some aspects of the substance and nature of personal data that can be collected and suggests a framework for more systematic analysis. The kind of data gathered is one piece needed for a broader ecology of surveillance. When the dimensions noted here are joined with other dimensions for characterizing surveillance —the structure of the situation and the nature of surveillance means and goals, we have a fuller picture and a framework for systematic analysis and comparison at the micro and middle ranges. A formally, if not substantively, equivalent framework is also required as we look comparatively across time periods, societies and cultures.

Trends and Counter Trends in Surveillance

In conclusion let me move from the specific focus on what surveillance collects to some more general empirical trends and speculations about identity and surveillance in recent decades that suggest issues for research.

- The decline of anonymity. The ability to be unnoticed

(which involves multiple dimensions) has declined significantly, although this

is not the same as being uniquely known.

- Making the meaningless meaningful. Once noticed

the ability to remain unidentified, whether by core identity, or some other

specific measure has declined.

- Colonization of time, space and physical borders. Whether voluntarily or involuntarily on the subject’s part, the

ability to discover and track the varied forms of individual information in

real time across physical barriers, locations and over time has significantly

increased.

-

Increased validity (if still far from ideal for

many purposes). When correctly applied, current core identification

technologies show a high degree of validity relative to the cruder Lombrosian

and eye witness techniques of the 19th century. Validity and understanding of

current empirical events, competencies and experiences on the average is

stronger than for those in the past and the latter in turn tend to have a

greater validity than for future predictions.

-

Category expansion. There is a significant

expansion of ways of measuring and classifying individuals and contexts that

are retrospective, as well as prospective. These abstract characterizations

that symbolize personal characteristics involve behavior as well as presumed

essence (whether physiological or moral). These often are, but need not

necessarily be, attached to a core identity. These involve greater precision

with respect to traditional measures, as well as composite measures that are

increasingly removed from the “natural” relatively uncomplex factors which

composed personal information prior to, and even during industrialization.

-

The merging of previously compartmentalized

data. The ability to be known about as a result of combining indicators has

significantly increased.

-

Apart from technical developments that permit

involuntarily collecting personal information, there has been a major expansion

of laws, policies and procedures mandating that individuals provide

information. Whether related to effectiveness, crises, or fairness, access to

participation in modern life (voting, government benefits, employment, building

or gated community access etc.) increasingly requires some form of identity

validation.

-

The integration of life activities with the

generation of personal data. We increasingly live in ways that automatically

provide personal information as part of the activity –i.e., the use of credit

cards, communication and driving.

- The blurring of lines between public and private places makes personal information more available. Note the privatization of places traditionally seen as “public” such as shopping malls and industrial parks (with legal means of collecting personal information). Or consider the blurring of the lines between home and work and the merging of public and private data bases and the ability of technologies to reveal some aspects of what is within a private space without the need to literally enter it, e.g., thermal imaging or cameras in pubic places that aimed at private places. Other examples are the availability of web and related searches in finding and merging personal information that had been de facto private because of spatial and temporal separation and the presumed ability to learn about non-consenting individuals by generalizing from those sharing attributes who voluntarily provide.

These trends suggest the familiar nowhere to run, tightening of the noose, decline of private space, privatization of public space, Leviathan all-knowing political, commercial and even interpersonal State of the dystopic imagination. Yet however powerful as an indicator of a social trend and as a raiser of consciousness, this view must be tempered by noting opposing developments.

In the midst of some impassioned political demonstration in the 1960s I recall a conversation that began, “if I had not believed it, I never would have seen it.” Certainly to a degree, “where you stand depends on where you sit”. Some of what we see depends on how and where we look. But much does not. There really is a reality out there and it is much messier than many of those studying surveillance and social ordering through technology acknowledge.

The current situation is dynamic and rapidly changing. Some opposing trends involving the ironic vulnerabilities of any system of control, as well as broader historical trends can be seen. Among some counter trends:

-

Increased freedom of choice. Individuals in some

ways are freer both morally and tactically to make or remake themselves than

ever before. Some identities that historically tended to be largely inherited

such as social status or religion can more easily be changed. Other identities have become culturally more

legitimate, such as divorce and homosexuality, out of wedlock birth, adoption, with

a subsequent decline in traditional stigmas and the need to be protective of

certain kinds of information. 59 Even seemingly

permanent physical attributes such as gender, height, body shape or facial

appearance can be altered, whether by hormones or surgery or beauty

parlors. The ultimate is the emerging

technology of total face transplants. 60

-

Television “make over” shows and self-altering

products reflect related strands of this.

These developments imply the emergence of a more protean self and the

self as a commodity and an object to be worked on, just as one would work on a

plot of land or carve a block of wood. Identities in some ways are becoming

relatively less unitary, homogeneous, fixed and enduring, as the modernist idea

of being able to choose who we are continues to expand, along with

globalization processes. This is aided by the expansion of non-face-to-face

interaction. 61

-

New opportunity structures for exercising

choice. The distance mediated interaction of cyberspace which calls forth new

means of authentication also opens up a vast potential for offering various

forms of alternative or prevaricated individual information. Cyberspace as play

(service providers such as AOL offering on-line aliases and fantasy chat rooms)

encourages this.

-

New functional alternatives to core identity.

The absolute number and relative importance of non-core forms of identity

offering varying degrees of anonymity has increased. There is a significant

expansion in the variety of pseudonymous certification mechanisms intended to

mask or mediate between the individual's name and location, yet still convey

needed information. As more and more actions are remotely tracked in cyberspace

(e.g., phone communication, highway travel, consumer transactions) the

pseudonym will become an increasingly common and accepted form of presenting

the self for particular purposes (whether as a unique individual or as a member

of a particular category.

-

Enhanced chances for neutralization. Beyond the

expansion of life style/identity choices we see the ironic emergence of markets

for counter-surveillance offering a vast array of methods to protect individual

information, whether by blocking, distorting, deceiving or destroying the

surveillance means. (Marx 2003) Much of this represents a righteous response to

the creeping or galloping expropriation of personal information, yet some also

represents new opportunity structures for violation. The ease of presenting

fraudulent identities divorced from the traditional constraints of localism and

place and time is central to crimes of identity theft. 62

-

Significant improvements in technologies for

protecting individual information. With encryption there is the potential for a

degree of confidentiality in communication, and enhanced accountability and

data protection never before seen. Technologies and services for protecting

personal information are increasingly available, from shredders to home

security systems to various software and privacy protection services.

- New normative protections and awareness. There has been a significant expansion of laws, policies and manners that limit and regulate the collection of personal information and its subsequent treatment.63 There has been some growth in choice and opt-in systems.64 This ties to the broader 20th century expansions of civil liberties and civil rights, as well as to particular crises. Whether these go far enough, are effective, and how they compare across institutions and cultures are important research questions.

These opposing trends work against sweeping generalizations

beyond this one against sweeping statements. Considered together some of the

above developments are ironic and contradictory, I take this as a sign of

reality's ability to overflow our either/or categories and the need to avoid

simplistic theorizing, as well as the need for empirical research.

TABLE 3

Some Dimensions of

Individual Information

| 1. Personal | ||

| Yes | No (Impersonal) | |

| 2. Intimate | ||

| Yes | No | |

| 3. Sensitive | ||

| Yes | No | |

| 4. Unique Identification | ||

| Yes (distinctive but shared) | No (anonymous) | |

| Core | Non-core | |

| 5. Locatable | ||

| Yes | No | |

| 6. Stigmatizable (reflection on character of subject) | ||

| Yes | No | |

| 7. Prestige enhancing | ||

| Yes | No | |

| 8. Reveals deception (on part of subject) | ||

| Yes | No | |

| 9. Strategic disadvantage to subject | ||

| Yes | No | |

| 10 Amount and variety | ||

| Extensive, multiple kinds of information | Minimal, single kind | |

| 11. Documentary (re-usable) record | ||

| Yes [permanent?] record | No | |

| 12. Attached to or part of person | ||

| Yes | No | |

| 13. Biological | ||

| Yes | No | |

| 14. "Naturalistic" (reflects reality in obvious way, face validity) | ||

| Yes | No (artifactual) | |

| 15. Information is predictive rather than reflecting empirically documentable past and present | ||

| Yes | No | |

| 16. Shelf life | ||

| Enduring | Transitive | |

| 17. Alterable | ||

| Yes | No | |

Back to Main Page | Top | Bibliography | Notes

Adey, P. (2004)

“Secured and Sorted Mobilities: Examples from the Airport”. Surveillance and Society. 4. Feb.

Allen, A. 2003, Accountability for Private Life.

Alpert, S. 2003. “Protecting Medical Privacy: Challenges in

the Age of Genetic Information”. Journal

of Social Issues, vol. 59, no. 2.

Altheide, D. 1995. An Ecology of Communication: Cultural

Forms of

Control. Hawthorne, N.YH.:Aldine de Gruyter.

Baudrillard, J. 1996. Collected Writings, edited by

M. Poster. Stanford:

Bennett, C. and Grant, R. 1999. Visions of Privacy.

Bennett, C. and Rabb, C. 2003. The Governance of Privacy. Brookfield,

VT.: Ashgate.

Bloom, A. 2003. NORMAL Transsexual CEOS, Crossdressing Cops, and Hermaphrodites

With Attitude. New York: Random House.

Bogard, B. 1996. The Simulation of Surveillance: Hyper

Control in Telematic Societies. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bowker, G. and Star, S. 1999. Sorting Things Out.

Brin, D. 1998. The Transparent Society.

Caplan, J. and Torpey, J. 2001. Documenting Individual