Introduction to Windows into the Soul: Conference and Abstracts

Gary T. Marx

Within the next generation I believe that the world's rulers will discover that infant conditioning and narco-hypnosis are more efficient as instruments of government, than clubs and prisons, and that the lust for power can be just as completely satisfied by suggesting people into loving their servitude as by flogging and kicking them into obedience. In other words, I feel that the nightmare of Nineteen Eighty-Four is destined to modulate into the nightmare of a world having more resemblance to that which I imagined in Brave New World. The change will be brought about as a result of a felt need for efficiency [and seduction and fear –- as viewed 60 years later]

—Aldous Huxley, 1948

Dear Mr. Orwell:

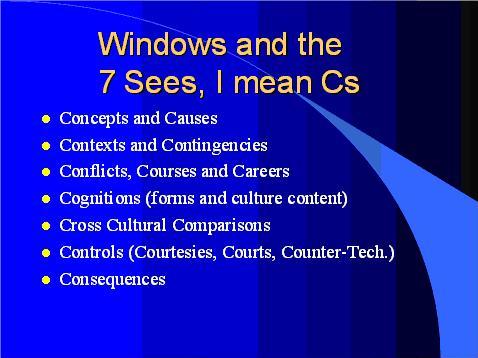

Since windows involve SEEing, holding apart whether this is bi-directional or one-way, one approach is to organize the topic around the 7 Sees, I mean C's. Mnemonics (a term easier to pronounce than to spell) offers us a way to remember. In that tradition (with a little liberty) let me offer the following 7 Cs for students of surveillance and society:

In the appendix to an early paper on privacy and technology (http://web.mit.edu/gtmarx/www/privantt.html) I listed almost 100 questions the topic raises. In the beginning there is the concept. We need to parse the rich flow of empirical reality into units. As social theorist G. Simmel suggested, "we are at any minute those who separate the connected and who connect the separate." We do this to document the variation in the world with respect to structures, processes and patterns that we seek to understand and to judge. We seek understanding as both its own end and to better apply knowledge. We are the Linneans and the Zolas of the social who, if we do our work well, can contribute to the work of the Solomons.

What do concepts such as surveillance, privacy, secrecy, anonymity, confidentiality, public, private, invasive and intrusive mean to different persons in different contexts and as defined and measured in different ways? What does it mean to say, "surveillance is neither good nor bad, but context makes it so"?

Having identified concepts we can measure, we can then explore correlations and causes. We need to know with better cross-observer clarity just what it is we seek to explain and to judge, control or facilitate. Much of the confusion in this area involves imprecise use of terms such as privacy and surveillance, without specifying what these mean, their specific settings and their myriad and varied consequences across time periods and for different social groups and values.

Central concepts for surveillance analysis are the characteristics of the means itself, the kind and form of the data collected (public, personal, private, sensitive, intimate) text, audio or visual and the goals and conditions of collection, protection and use. Making such distinctions can help us see continuity and ask just what is new about the new forms of surveillance.

In a forthcoming book I expand on the notion of the maximum security society (developed in the last chapter of Undercover), suggesting it consists of 11 related sub-societies:

Technologies of course reflect social factors, but they also have implications for them. Contingencies and contexts determine much of what we see and how we judge. These have distinctive logics (e.g., the treatment of children and adults, employment and citizenship, the role played, and whether or not there is choice and reciprocity and overlap or disparity in the goals of the agent and subject of surveillance). Identifying structural variation in contexts is central to better understanding. The relative poverty of our conceptualizations means that one size hardly fits all. There is a tendency to lead with our values without adequately considering the facts and how these (and our judgments) vary across institutional settings. Nor is the meaning of values adequately specified, nor how we might best deal with values in conflict.

Conflict and contention often travel with the topic. Surveillance tools and episodes involve political struggles that have careers and courses of development. This involves studying interaction and the process elements. This can also involve the effort to create cultural understandings. We may see cycles of greater and lesser surveillance and resistance to it, as well as directional developments across centuries, as with many of the themes of modernization.

The tactics are pushed and yet blocked or inhibited by many factors. What drives or brakes (and sometimes breaks) application? What controls, if any should there be? Should surveillance be mandatory, prohibited or discretionary and for whom and under what conditions? What are the rights and obligations of both watchers and the watched in different settings? This involves the emerging area of the sociology of information and attention to rules and behavior and expectations and sanctions around both concealing and revealing information.

An array of controls can be noted such as counter-technologies, codes, civil society, core values,including civil liberties, coercion, courts and laws, regulations and policies, conscience, and courtesies (manners, "don't stare", "please turn off your cell phone during the play").

Attention to cognitions reminds us that all ways of seeing are also ways of not seeing. We most commonly use words and numbers in discussing the topic, but how do we learn and experience the pleasure and the pain of being both watched and a watcher? What does music make us feel about the topic? How does the content of cartoonists differ from graphic artists who create ads? How have visual and performance artists communicated about the topic? The centrality of vision to surveillance fits the visual arts very well.

In an age of ever greater awareness of globalization, we also see the need for cross-cultural comparisons. Until recently, in China and Russia (lacking a civil society tradition), there was no word equivalent to the English term privacy. In many traditional communal societies there still isn't. What can we learn from the practices and controls of other cultures? Why doesn't the United States, unlike most other modern countries, have a strong privacy and freedom of information government commission? Under the pressure of common needs, global culture, the export of technology and fads and fashion, are we moving toward a standard world surveillance culture? Or will this be true only superficially, as unique local history, culture and social order filter and adapt world practices to their own particularities?

Then of course there are the consequences. This is the "so what?", "where is the beef?" question. What do these changes imply about the kind of society we are, becoming, might or should become?

In my introductory presentation I will selectively elaborate on the above. The conference papers fit within one or more of the 7 Cs. Happy sailing!

Session IA. Conceptual, Theoretical and Ethical Perspectives

Helen Nissenbaum, "Privacy in Context"

The sinister world of Gary Marx's 1990 "Case of the Omniscient Organization" incorporates a set of tensions by now familiar in present-day surveillance scenarios and a myriad other socio-technical systems that track, analyze, and disseminate personal information. Rational, from one perspective, these scenarios are nevertheless deeply disturbing. An abiding challenge has been to explain, systematically, what about them (if anything) is morally and politically objectionable. This challenge has motivated my own work, and ultimately, the theory of contextual integrity which I will briefly sketch in my presentation. Building on a rich set of commentaries and existing work on the nature and value of privacy, contextual integrity finds in the layer of social analysis the means to distinguish information practices that are acceptable, even commendable, from those that are objectionable. What is wrong with many contemporary practices is not only that they threaten the interests of information subjects and are resented, but transgress context-relative informational norms. By providing a concrete setting of a business organization, Marx's scenario is exactly the kind of test-bed that lends itself to contextual analysis. In my presentation, I will elaborate on the structure of context-relative informational norms, explain how they account for judgments about privacy, and explore conditions under which they may legitimately be overridden by novel information practices.

Christena Nippert-Eng, "Privacy and the Work of Secrets"

Privacy is a condition of relative inaccessibility. For the 74 mostly middle and upper-middle class Chicagoans in this Intel-funded study, privacy exists when the things they wish to be private are as private as they wish them to be. Within the constraints of its socially gifted nature, they try to achieve privacy through the process of selective concealment and disclosure. When participants lose control over this process – or learn they never did possess such control – they feel as if their privacy has been violated.

Secrets are the most private of participants' private things, requiring the most active and protective behaviors in order to keep them that way. Anything and nothing can be a secret; the form is analytically distinct from any content. Secrets are different from mere unshared information, however, as an active (if less than conscious) decision must be made for a secret to be born – and later, for it to die.

The work of secrets includes the work required to keep, reveal and find them out. Successful secrets work means keeping the secrets we want to keep, revealing the secrets we wish to share, finding out the secrets we want to know (or think we do) and making good decisions about all this in order to achieve the kinds of relationships we desire with others. Secrets are the currency of relationships, and managing secrets is a critical part of managing relationships, of both the wanted and the unwanted types. How we do the work of secrets matters even more than their actual content when it comes to judging our success in doing this work.

The work of secrets consists of 1) the actual craft of secrets work – the skills and techniques of managing secrets— and 2) decision-making about secrets, including whether or not to have them, share them, or find them out, and what might be the best ways to do that.

The "field craft" of secrets work requires attention both to tangible and intangible matters and to collective as well as individual efforts. Competency at secrecy is acquired. Like any other skill set, the skills of secrecy are learned, including the mindset necessary to engage in it.

The effort involved in making decisions around secrets is constrained by the life cycle of a secret. The birth and death of a secret are defined by decisions to protect or stop protecting is. Its duration consists of a series of decision-demanding moments. At these moments, the secret-owner's responses may range from cool and controlled to frantic and foolish. Disclosure/exposure or continued secrecy might occur due to any number of intentional and unintentional acts during this time.

Major factors affecting the decisions about secrets – i.e., whether or not to make, keep, reveal, or find out secrets – and how, exactly, to do this include: 1) beliefs about who owns the secret and the ways power is distributed around and connected to secrecy, 2) beliefs about how competent one is in the work of secrets – and how competent relevant others are, too, and 3) beliefs about the potential consequences of disclosure, exposure, and concealment for one's relationships with others.

Glenn W. Muschert, "Information, Openness, and Secrecy: On the Usefulness of Simmel to Surveillance Studies"

Using Simmel's (1906) article "The Sociology of Secrecy and of Secret Societies" as a stepping-off point, this talk examines Simmel's impact on social scientific studies of secrecy. A brief survey of the piece, and its position in the field leads to a first conclusion that Simmel's impact was rather diffuse at best. We then argue that what is needed is a Sociology of Information Framework (Marx & Muschert 2007) for the adequate study of information flows in contemporary society. Thus, we outline the framework and some related concepts connected to secrecy: public & private; confidentiality & secrecy; and some paradoxes of information. We conclude with suggestions about how Simmel's piece on secrecy might be usefully connected with his more famous (1907) piece on money. Considering information as an object of value subject to principles of exchange, we suggest a number of concrete propositions which might serve as bases for future research drawing on the Sociology of Information framework.

David Lyon, "Boston Bluefish and New Surveillance"

This paper takes a large view of surveillance, from Marx' early comments on the "new surveillance" to the present. The Undercover analysis showed how technological changes amounted to qualitative differences in surveillance. The technologies could be used jointly, and were both centralized and decentralized. The state's traditional monopoly over the means of violence was being supplemented if not supplanted by new means of gathering and analyzing information. The trend was towards a maximum security society. What has lasted from those first proposals about the key changes in surveillance? Marx's work highlighted the involvement of communication and information technologies in surveillance and he noted what James Rule called the corresponding expansion of surveillance capacities as a result. It sensitized us to developments in that field, especially searchable databases (Lawrence Lessig) and networked communications (Ericson and Haggerty). And it demanded hat serious attention be paid to regulation, limited as Priscilla Regan showed, to attenuated asocial models.

What could we not have foreseen? Marx noted the role of mass media and consumerism as parallel forms of cultural control, anticipating Zygmunt Bauman, Thomas Mathiesen, Mark Andrejevic, Hille Koskela on mass media and consumerism and also that of Oscar Gandy, that actually shows how surveillance works as a consumer sphere process. No one foresaw 9/11 of course, or the ways that subsequently surveillance trends not only converged but were deliberately racheted up, fostering further fears of just what Marx had warned of a decade-and-a-half earlier.

What kinds of tools — analytical and theoretical — do we need now? The technological changes are still crucial but the cultural and political-economy questions are also indispensable in the twenty-first century. Some of the pioneering ideas of Marx must still be woven into Surveillance Studies; not least his concern with the everyday human dimensions, mediated by Goffman's self-presentation or Simmel's stranger, along with the popular cultures of surveillance. The careful taxonomies – perhaps Marx's signature contribution — are also vital to nuanced analysis of surveillance that recognizes complexity and ambiguity. Beyond this, the political economy of surveillance – the corporate role in fostering surveillance of all kinds has become a sine qua non.

What stance should be taken towards surveillance? As a basic organizing principle of contemporary institutions surveillance may attract a fundamental critique but Marx's approach has always been to acknowledge and explore both the ambiguities and moral paradoxes of surveillance. He says, for example, "we need protection not only by government, but from it." This, because within supposedly democratic societies, a velvet glove hides an iron fist. Marx's work is predicated on the hope that social science can "make a difference."

Session IB. Conceptual, Theoretical and Ethical Perspectives

Ian Kerr, "Emanations, Snoop Dogs and Reasonable Expectations of Privacy"

Ian Kerr will report on the recent Canadian case of R. v. Tessling which raises broad and important questions about the nature of privacy and autonomy in a world of ubiquitous information emanation. His work with Jena McGill expresses concern about an increasingly problematic judicial approach to the reasonable expectation of privacy in odour emanations, arguing that a failure to clarify Tessling in the snoop dog cases and in the broader context of ubiquitous information emanation, especially alongside the maintenance of reductionist, non-normative approaches to informational privacy across Canadian courts could seriously diminish privacy rights. http://www.idtrail.org/content/view/667/

Anne Uteck, "Spatial Privacy in a Networked World"

In an increasingly mobile society, location has become a new commodity giving rise to technologies such as wireless cellular devices, global positioning systems (GPS), and radio-frequency identification (RFID). These developments enable geographic information systems (GIS), location-based services (LBS), E-911 initiatives, as well as facilitating proposed greater access for interception of communications by state and private sector. The development of these systems and initiatives reflect a combination of political, economic and cultural factors motivating the production of new technologies that can locate people and objects and track their movement from one place to another. These factors include a shift towards a safety and security state, a desire to realize the potential profitability of integrated and accelerated forms of organizational management and a cultural commitment to efficiency, productivity, convenience and comfort. "Where are you?" has become the new "How are you?"

This new wave of powerful technologies are finding their way into our homes, cars, cellular phones, identification documents and even into our clothing and bodies. No longer the stuff of science fiction, emerging location and geospatial technologies are beginning to weave themselves into the fabric of everyday life. Within a context of growing technological convergence, they have the unique ability to locate and track people and things anywhere, anytime and in real-time. Clearly, there are some compelling advantages to such enhanced capability. For example, emergency services are better able to find accident victims, the ability of commercial organizations to improve the way they do business by fleet, product and employee tracking, parents can secure location devices on or in the bodies of their children for safety reasons, government intelligence, law enforcement, port authorities and correctional facilities can manage risk and provide increased security applications. However, accurate, continuous, real-time location tracking in the physical world made possible by emerging technologies also creates a different set of concern. Among these concerns are new forms of surveillance, fresh challenges for privacy and the potential to erode traditional notions of personal space and socially recognized boundaries. These concerns are even more pertinent as the technologies are combined, integrated, connected, invisibly and remotely to networks, forming part of a wider movement towards a society characterized by ubiquitous computing, In the ubiquitous networked society, computing devices are embedded in everyday objects, places and people, operating in the real world. Location-aware technologies exemplify what is referred to as geosurveillance, a mode of surveillance characterized by the ability to track location across spatial territories . As a result, our physical and personal space is increasingly vulnerable and the core privacy interests individuals have in sustaining protection of theses spaces is potentially compromised. This is deeply problematic, particularly over the long term as networked location technologies destabilize private and public environments and challenge our fundamental ideas about space and the privacy expectations that go with them There is, therefore, a need to ensure that privacy policy and law adequately considers the enhanced surveillance capabilities and the full range of privacy interests implicated by emerging networked location technologies.

Pris Regan, "STS Approaches to Privacy Protection"

Pris Regan will report on her joint work with Professor Deborah Johnson. Privacy policymaking has tended to address new technological threats to privacy by finding the most appropriate analogy with either a pre-electronic or existing electronic system and then developing privacy policies for the new technology based on the familiar one. For example, face recognition technology is thought to be non-intrusive since taking photographs in public places is not considered an invasion of privacy; obtaining access to an individual's email is thought to require a warrant because email is seen as comparable to telephone communication and access is, therefore, thought to be parallel to wiretapping. The result of using this approach has been twofold: the new technological threat is analyzed in terms of the privacy theory that was associated with the traditional technology; and existing legal frameworks are used as the starting point for the development of new legislation. In the United States, this has meant that the "fair information practices" model and the Fourth Amendment "reasonable expectation of privacy" model have been twisted and turned to accommodate virtually all new communication and information technologies (CITs) — with generally unsuccessful results.

In what follows, we step back from this backward-looking, legalistic, and pragmatic approach which has dominated much of the privacy policy discourse and try to develop a new framework for understanding privacy and generating new policy approaches. We draw on insights and theories of the relatively new field of science and technologies studies (STS).

STS theory cautions against three mistakes that are often made in thinking about technology...

STS scholars argue that a technology cannot exist or function or achieve its intended or unintended purposes without all of the parts (nodes in the sociotechnical system) working together…

In this paper, we adopt a sociotechnical systems framework with six dimensions and we use this framework to describe and understand two different systems. Our analysis seeks to understand how these dimensions affect and constitute conditions of privacy.

Oscar Gandy, Jr. "Race and Cumulative Disadvantage Engaging the Actuarial Assumption"

By the turn of the century, the analysis and management of risk had escaped the bounds of professional concern and scholarly expertise to claim a prominent place in the public consciousness. The Information Society had become the Risk Society, and the arcane wizardry of actuaries and statisticians became common, almost essential features of popular mass media fare. Estimates of probability based on analyses of events in the past have come to dominate decisions about the paths we should take in the future. Nothing worthy of our attention can avoid an assessment of chance.

This book is about the ways in which the application of probability and statistics to an ever-widening number of decisions about things that matter serves to reproduce and reinforce disparities in the quality of life that different sorts of people can hope to enjoy. For some people, it seems that if it weren't for bad luck, they wouldn't have any luck at all. The impact of bad luck seems to cumulate rapidly over time, such that a bit of bad luck early in life increases the probability that losses will mount, and the gambler's dream of breaking even, or getting ahead in the game eventually gives way to despair. We are just beginning to understand how well we do in the natural lottery that distributes genetic endowments at birth helps to determine how race, gender, and social class combine to influence the character and range of opportunities or life chances we will encounter along our way toward the end of the game of life. This book examines the ways in which public policy and private action further shapes the design of a variety of games that we may or may not see as fair. Policy decisions, informed by statistical analysis, shape the opportunities people face in the markets for education, employment and health. Strikingly similar analyses also determine what we can expect when we take our chances with the courts and the criminal justice system. Special attention is paid to the role played by an actuarial logic that informs routine decisions about access to financial resources, including insurance, that govern far more than access to credit. The mass media play a critically important role in shaping the ways in which we understand the role of luck in our lives, and in the lives of others. The ways in which the media frame the life chances that different groups confront helps to determine whether the public supports, opposes, or ignores proposals to modify public and private activity in these critical areas. This book provides an analysis of tendencies within the media that ironically serve to reinforce disparities among people that investigative journalists had initially hoped to reduce.

Challenging the actuarial logic that shapes the distribution of life chances in society is an exceptionally difficult challenge. This book represents the first draft of a declaration of independence from its imperialistic grasp, and a call to oppose its spread.

IWBL 3/20/08 2

Chapters

Session IIA. Empirical Inquiries: Laws and Orders

Peter K. Manning, "Surveillance: From them to us and Back to Them"

In this paper I challenge the idea that surveillance is a) one-way b) onlya concern to the middle classes c) best understood via the works of Foucault. I will develop a notion that the "Foucault frenzy" has misdirected our attention from the true targets (and victims of) of surveillance- young, black men in disadvantaged areas of large cities, e.g. Boston. I have written some introductory material about the changed nature of spying surveillance etc, especially in the 20th century. Surveillance as presently discussed is middle class-identity-loss-social capital and symbolic damage based. These issues, while important, and an extension of Foucault, distract us from the fundamental damage done to the poor and African Americans - by surveillance, arrest, unequal courts and police and extended inequalities. Who is being surveilled with what damage? I will describe the latest Boston "consent search" and video and audio surveillance in the neighborhoods of Dorchester and Roxbury.

James Byrne, "The Best Laid Plans: The Varied Consequences of New Technologies for Crime and Social Control"

I will offer an overview of both hard and soft technologies of crime control. I will discuss 4 controversial Ps. (1) Precrime/prediction, (2) Private sector, profit, and the decline of Public Justice, and (3) People technology vs. thing technology( replacement of the former with the latter), (4) Privacy (disappearing) in the name of protection( false promises, profit, and the military-criminal justice connection). I will then turn to a consideration of some intended and unintended consequences in police, courts and corrections.

David Cunningham, "Ambivalence and Control: Monitoring the Civil Rights-erea Ku Klux Klan"

Models that purport to explain the interplay between dissidents and the state generally assert, either explicitly or implicitly, that the path from state interests to action to outcomes is a linear one. Using the case of the United Klans of America (UKA) in North Carolina, I argue that state efforts to exert social control upon a perceived threat to the status quo are shaped by a range of internal and external contingencies. In particular, I undertake an comparative analysis of two state agencies to demonstrate how a particular mechanism — ambivalence, here conceptualized as a mismatch between organizational culture and organizational goals — leads to distinct, and sometimes heterogeneous, actions and outcomes not directly traceable to organizational interests. Findings lend insight into how the interplay of endogenous organizational elements shapes contentious political outcomes in potentially divergent ways. I will tell two diverging historical stories, drawing out some key implications of the divergences.

Elizabeth Joh, "Breaking the Law to Enforce It: Regulating Undercover Policing"

Chris Schneider, "Popular Culture, Surviellance and Social Control"

This presentation will investigate how social identities, social interaction, and social control efforts are informed by media entertainment formats and new information technologies. A basic contention is that popular culture is cultivated to enhance the integration of communication and information technologies into an effective, controlled, and accepted communication environment. The principle argument this paper advances is the idea that popular culture reinforces existing facets of both formal and informal aspects of social control while also contributing to the creation of new and unforeseen aspects of social control.

Session IIB. Empirical Inquires: Other Applications Politics, Work, Education, Health and Families

Colin Bennett, "What Makes a Privacy Advocate? The Actors, Groups and Networks of Anti-Surveillance"

As new information technologies have been introduced to public and private organizations so fears have grown for the unregulated collection, use and disclosure of personally identifiable information, and for the potential for unacceptable levels of surveillance. We already know a great deal about the actual and perceived risks from the unregulated processing of personal information. We also have evidence from numerous surveys that there are high, and perhaps rising, levels of public concern in many countries in most regions of the world. Other research has highlighted the many forms of resistance which individuals use to thwart, circumvent, or disrupt intrusive technologies and practices.

If surveillance is a central condition of modern societies and if its social, economic and political consequences are so widespread and profound, then why have we not witnessed a more visible and coherent anti-surveillance movement? So far collective action has been expressed through the varied activities of people who self identify as "privacy advocates." This is a sprawling, decentralized and under-resourced network which has emerged in many countries to bridge the gap between a concerned, but ill-informed, mass public, and the governmental and business organizations that process personal information. There is evidence, however, that these individuals are becoming increasingly networked and have thus gained a greater influence because of a number of high-profile conflicts.

This paper will attempt to profile this international privacy advocacy network, and categorize the kinds of groups and individuals that self-identify as "privacy advocates." I analyze how these actors frame the issue, and the various resources they bring to bear on the problem. The network is loose, open-ended and spontaneous. It comprises many diverse groups which grow and die, divide and fuse, proliferate and contract. It possesses multiple, temporary and sometimes competing leaders or centers of influence. As such it is very similar to the transnational advocacy networks associated with other human rights and consumer issues. In conclusion, I argue that this network is more important than people often recognize, and that its significance will only increase. The paper is based on extensive interviews with key informants in the privacy advocacy network, and is drawn from a forthcoming book: The Privacy Advocates: Resisting the Spread of Surveillance (MIT Press, 2008).

Torin Monahan, "Care and Control with Hospital Positioning Systems"

Hospitals in the U.S. are increasingly turning to real-time location systems (RTLS) to manage the complicated flow of devices, inventory, medication, staff, and patients in these healthcare settings. The most common of these systems rely on radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags affixed to inventory or embedded in staff badges or patient wristbands. These tags are automatically "read" by detectors placed in hallways, rooms, drug cabinets, or at the entrance to portals such as elevators. Various kinds of graphic user interfaces allow for staff to track the location of items or people, ostensibly enabling staff to speed up patient care while minimizing the need for redundant inventory.

Our primary, ethnographic research on RTLS in U.S. hospitals has found that the administrative parties championing such systems can meet with serious resistance, especially from nursing staff who perceive the systems as heightening management's surveillance of their workplace activities. In extreme cases, where nursing staff are completely cut out of the decision-making process and are not given persuasive reasons to cooperate with RTLS, they have turned to sabotaging the system by removing and destroying radio-frequency identification tags from inventory and refusing to wear the tags themselves. In all cases, however, there is a noticeable reluctance on the part of administrators to codify formal policies for the use and maintenance of RTLS in hospitals; thus, ongoing communication and negotiation must take place as new uses – such as staff surveillance – are discovered for these emergent technological systems.

Graham Sewell, "Performance Measurement as Surviellance: When (if ever) Does ‘Measuring Everything That Moves" at Work become Oppressive?"

Graham Sewell will report on his work with James R. Barker. The relationship between performance measurement and performance management continues as a central concern for management scholars and practitioners. There is evidence to suggest that the legitimacy of performance measurement instruments is likely to be high so long as they are seen to be objective and their administration is perceived to be impartial. We associate these ideals of objectivity and impartially with a technocratic discourse of protection or "care"—disinterested managers measure the performance of others to serve the interests of everyone in the organization (e.g., to expose free-riding, to reward employees' efforts fairly, to improve organizational performance, etc.). This contrasts with a critical discourse of "coercion"—performance measurement is administered by managers to serve the interests of a minority (e.g., by intensifying work, reducing operating costs, increasing profits, etc.). We argue that by positioning performance measurement as a form of surveillance, we can accommodate both perspectives on its purpose and consequences. We demonstrate how engaging the ambiguity of organizational surveillance helps us to understand the paradoxical status of performance measurement as it is experienced by employees.

John Gilliom, "Teaching to the Test: Surveillance as Policy Implementation in No Child Left Behind"

The presentation will frame the educational testing under No Child Left Behind as a significant and important surveillance initiative which is now undergoing a major pushback in the form of political and social opposition. I will then use the situation as a vehicle, or starting point, to discuss a number of issues that face surveillance research. In this sense, I think it should work very well for a verbal presentation, because it will give me a chance to briefly touch on a number of interesting hits in the area — opposition and resistance (natch!), thinking about the changing nature of governance, ulterior political motives in "neutral" policies, and the importance of embracing both history and the mundane in surveillance research.

Val Steeves, "The Watched Child: Surveillance in Three Online Playgrounds"

Val Steeves will offer a social, ethical and legal analysis of three web sites focusing on children, including Neopets, Barbie.com and Webkinz. She will examine the business models behind these sites, and explore the ways in which these sites reconstruct our understanding of privacy to promote a business agenda based on seamless surveillance. She will argue that these sites mine children's play and communication to manipulate their social relationships and sense of self, embedding their brand into the child's private life. This constitutes a profound invasion of children's online privacy, and significantly restricts the potential of the Internet to play a constructive role in children's lives. To fully protect children's online privacy, policy makers must encourage the creation of public spaces on the Internet in which children can play and communicate free of commercial manipulation, and support the development of media educational initiatives that support children's critical engagement with online marketing.

Session IIIA Discussion of Surveillance Issues

This is the most open ended of the sessions. Three scholars (Kevin Haggerty, Stephen Margulis, Jay Wachtel) with very diverse backgrounds and experiences will strain what they have heard thus far (or will read in this file) through their prisms and also offer brief comments on surveillance issues they find of particular interest/importance. This session will also hopefully offer additional time for discussion not possible in previous sessions.

Jay Wachtel will discuss the need to intercede before terrorist events occur. Given their lesser vulnerability to infiltration than ordinary criminals, the interception of wire and wireless communication loom large. However, unlike informers, who require no judicial blessing, tapping requires that police convince a judge there is probable cause a serious crime is being planned or committed. "Probable cause" means more likely than not, a standard that's tough to meet when bad guys are so secretive that conventional methods don't work.

What's the fix? Adopt a standard, much like the Terry stop-and-frisk, allowing police to intercept and "detain" communications given reasonable suspicion that at least one of the parties is promoting terrorism, under court supervision and within set time limits. If probable cause is reached then cases could proceed along a conventional track. Two postings explaining this concept in more detail are at: http://www.liberalpig.com/html/terrorism.html

Session IIIB Surveillance Issues in Comparative Perspective

Emily Smith, "The Surveillance Project's International Survey on Surveillance and Privacy: Traveller Perspectives"

The Globalization of Personal Data (GPD) project, a international, collaborative and multi-disciplinary research undertaking of the Surveillance Project at Queen's University in Kingston, set out to examine the increasing flows of personal information and how ordinary people- citizens, workers, travellers, and consumers- respond to these flows. The largest undertaking within this project was an international survey on privacy and surveillance, led by Elia Zureik, conducted in nine countries with almost 10,000 respondents using the same survey instrument. Construction of the GPD survey occurred in many stages over four years. The final survey contained fifty questions on topics including knowledge of technology and laws, control over personal information, trust in government and private companies, actions taken to protect personal information, experiences of surveillance, national ID cards, media coverage, terrorism and security, CCTV, and some questions directed at workers, travellers and consumers in particular. The grand scale of this project leaves many layers of this data yet to be explored. A subset of data on air travellers will be examined here. The personal information of travellers is increasingly being collected and shared among numerous agencies, with the public being largely unaware of this occurrence. The GPD survey reveals the responses of travellers as subjects of surveillance to these flows in internationally comparative perspective.

Elia Zureik, "Workplace Surveillance: An International Survey"

Three main dimensions characterize research on workplace surveillance: legal, policy, and socio-psychological. Two approaches are identified with legal studies of workplace surveillance: the property and the rights approach. The first is anchored in the notion that the workplace is the property of the owner and as such privacy guidelines are the prerogative of the employer. The rights approach, on the other hand, draws its inspiration from the literature on individual rights and relies on the "reasonable expectation" principle associated with individual privacy. The policy approach situates workplace privacy concerns and their ethical dimensions in the context of existing regulatory measures in the private and public sectors that are designed to reconcile the rights of individuals (as workers, consumers, employers) in the face of technological advances regarding the transmission and storage of information, on the one hand, and organizational/ governmental claims, on the other. The socio-psychological approach examines the attitudes of citizens in their various role capacities to the impact of surveillance technologies in the workplace. Stress is placed on personal autonomy and dignity as they are affected by intrusive surveillance measures.

The International Survey of eight countries explored the attitudes to employers accessing the email of employees and monitoring their performance through the use of CCTV. Questions in the survey allowed us to assess the relative importance of the property approach compared to the individual rights approach, and situate the results in specific country characteristic such as regulatory policies and other legal measures. As well, we correlated the answers given to these questions with basic demographic characteristics in each of the eight participating countries.

Bob Hoogenboom

Surveillance studies, the panopticon, maximum security society and the like are main concepts of this conference. However, many of these concepts seem to be to much more rooted in ideological contexts than solid empirical research. Although very useful as 'sensitizing concepts' (and of course many technological developments are taking place) the 'bittersweet' surveillance realities are such that political, legal, bureaucratic & cultural contingencies are very persistent. Not to mention technofallacies (Marx), disinterest and mere stupidity of low level employees and the structural failing of large scale IT-projects both in the public and private sector. Police research and criminology is rich in colourful stories of turf wars, guerre des flics between law enforcement agencies, not to mention "The Wall" between political and criminal intelligence. Coalition forces in Iraq don't seem to be gaining any substantial ground with the large scale deployment of 'network centric warfare', combining satellites, data, audio, airplanes, sensors and virtual intelligence in helmets of soldiers. Network centric warfare is one of the ultimate fantasies or nightmares, depending on your point of view, of the future of surveillance yet not without some pifalls it seems.

I am finishing a book on port security in two of the biggest harbors in Europe (Rotterdam and Antwerp) using a 'governance of security' perspective. Some conclusions: different control agencies (law enforcement, inspections, private security, intelligence) operate in 'multiple realities'. They have their own distinct tasks, responsibilities, legal frameworks, cultures and interests. Information sharing is increasing but doesn't come close to the Jeremy Bentham drawings. Causes for the inconsistencies between the ideological concepts and empirical realities are to be found in the relative neglect of theoritical and empirical findings from police research (turf wars, police culture, management-street cops), business administration (the structural under use of information in the organisations and the over stretched view we have on the rational nature of IT-processes), public administration (rule of law, bureaupolitics, street level bureaucracy), intelligence studies (the over stretched rational and supposedly effective nature of the agencies; see for instance Legacy of Ashes (2007) on the history of the CIA), criminology (private justice mechanisms and overall techniques and strategies to evade state interference) and political science (many security policies have a ritual, political symbolic, meaning). And more recently the multidisciplinary debate on the boundaries of security because of economic interests are also sharpening the debate on the actual extent of security measures and policies. There are economic checks on security.

Consequences are we have a lack of local knowledge (Geertz) on what surveillance actually is and is not. There are many 'big stories', but a relative lack of differentiated (and empirical) stories. From a cognition point of view we must (re)read the panoptic classics (from Darkness at Noon to 1984 and everything in between), we must (re)view film classics like Enemy of the State (wonderful), The Net and The Conversation but also read Dilbert cartoons to understand organizational irrationalities, management instruction films by John Cleese to be aware of organizational stupidities, The Insider to have faith in ethical motivated individuals who 'rage against the machine' (listen to the pop band with the same name), or make an inventory of worldwide surveillance techniques (camera's, audio) given out by human rights organizations to record abuse and mistreatment or accidental homemovies influencing social life (as in the Rodney King case).

Minas Samatas, "Surveillance Issues in Comparative Perspective : The Greek experience"

While many of the world's nations are becoming surveillance societies, in Greece, there is a growing resistance to police surveillance, especially after Athens 2004 Olympics, and the pressure by the Greek Government to use the expensive Olympic CCTV cameras as a panacea for all problems, from traffic control to crime and terrorism, urban and sports violence. There is a growing opposition and resistance by mayors, civil society groups, academics, anti-surveillance NGOs and concerned citizens, even by the police union and especially by the Greek Data Protection Authority (DPA), which has recently resigned in protest for the Government's surveillance policy. Greek people fear and mistrust state surveillance because of their past police-state experience of authoritarian, repressive thought-control surveillance . At the same time, especially the young people, ignore or don't bother about non state surveillance.

Given the policy of expansion and resistance in Greece, I will very briefly correlate :

Session IV. Surveillance and/in Art

Julia Scheer, Natalie Bookchin, T. Kim-Trang Tran and Rachel Mayeri will discuss and show their response to the issues through their art. Time permitting, we will show Rebecca Barron's film "How Little We Know of Our Neighbors."

Session V. Discussion: The Surveillance Society "What Do We Gain and What Do We Lose?"

Larry Gaines will consider the potentials and implications of surveillance for local police.

Stephen F. Rohde will survey the most prominent assaults on privacy in the post 9/11 era from a civil liberties perspective and focus on the inversion of the pre-9/11 model in which the government was expected to operate largely in public and the individual enjoyed a wide zone of privacy.

James Rule will focus on the limits of official privacy protection policy, identifying issues and challenging us to think about what remains uncomfortably unresolved, even if the consensual "fair information practices" were rigorously and universally observed.