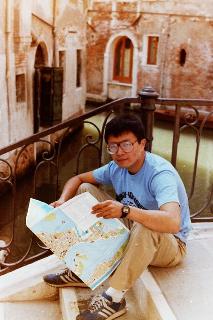

Nam in Venice.

Nam brings calamity upon himself. And he knows it. I'm sure that the death of the 2002 was caused by his failure to check the engine oil level ever since he had bought it. Whenever confronted with such malfunctions of common sense, he would give me that grin, half sheepish and half wicked, with that one eyebrow twitching involuntarily as if to say: "Sure I'm absent-minded. But ENGINE OIL is just not what life is all about." But what is life all about then? The answer evolved constantly. For a while it was physics, the noblest of the sciences, seeker of Truth. Then Sartre and Camus suddenly became popular. The poetry of Wallace Stevens. Thomas Mann. Then the cinema. Goddard, Coppola, Kurosawa, Bergman. Making a quick million so he could pursue these higher ideals became an obsession. He began to invent things. He started a company based on a patent he filed for a new kind of electronic compass. Sadly, however, common sense and an ever-present mind are de rigeur for success in business; Nam was powered out of his own company by his two partners (who, in a perfect caricature of a bad soap opera, fell in love with the same woman, fought over her, and in the meantime dissipated the assets of the business). Oh yes, and women. They were in and out of Nam's focus of mind: at times he could be uncomfortably misogynistic; at other times he would be unbearably romantic. In the early years of our friendship, I was embroiled in an obsessive love affair which made me oscillate so completely across the my emotional spectrum that he would swing his attitude toward women in empathy with whatever state I was in.

The entrepreneurial stage lasted for a while. I even got sucked into helping from time to time; I can't deny that visions of an independently wealthy lifestyle had allures for me, too. During one such venture we cranked out all-nighters during graduation week in the basement machine shop of the physics department cutting, rolling, and welding copper sheets. Nam had visions of parlaying his honors project into a breakthrough technology for magnetic resonance imaging (then still called the politically incorrect nuclear magnetic resonance imaging) by using a special type of resonant cavity rather than the expensive and bulky electromagnetic coils. At the time, the medical imaging industry appeared to be a burgeoning juggernaut which would rake in billions of dollars within a few years. We would patent the design and sell it to GE or Phillips for a not-to-be-sneezed-at sum. Unfortunately the design turned out to be fundamentally flawed for such applications and we were left only with a shiny and impeccable piece of copper sculpture and several nights worth of sleep debt.

Occasionally I would pick up the phone to hear a wired Nam on the other end asking me for my opinion on a new idea. Wireless headphones. LCDs for calculators to be sold in the Arab world (I thought this was a joke: don't we use Arabic numerals?). Heat recyclers for commercial clothes dryers. Car phones programmed to call the police if the vehicle was stolen. Usually I would play the skeptic--no, strike that "play"--I was a skeptic.

Once I put another friend into a compromising situation by telling Nam that he (let's call him Bill) was not happy with his work and was considering starting his own company. Bill was the chief mechanical engineer for an advanced electric car project, and this news sent Nam into a frenzy of speculation and scheming. After talking to Bill and confirming his disgruntlement, he began negotiating with Hyundai headquarters for a contract to develop an electric car which would be the envy of the Japanese, Europeans, and Americans; in effect, he promised them Bill. By the time Bill and I found out, the agenda had advanced to the point of a Hyundai executive planning a trip to the U.S. to meet Nam and the renegade engineer. Bill immediately had his father, an L.A. lawyer, call Nam to advise him that it was in the best interests of all involved to formally retract Bill's name from the discussions with Hyundai. Or else. Nam was stunned. He had no idea that he had blundered into potential lawsuit territory. He complied with the polite yet transparently threatening request, and the trans-Pacific venture folded like a dyslexic poker player who suddenly realizes he's short of a straight by a card.

Another time he was hiding from a lawyer for real--at my house, of course. He had rear-ended a car stopped at a red light in Berkeley. He was looking at his date and "tickling her chin." A guy walked out of the lawfully stopped car, they called the police, exchanged addresses, and had their cars towed away. A few weeks later Nam received a letter from a lawyer informing him that the client was suffering from a serious neck injury and that steps were being taken to request a monetary compensation from the party at fault.

Nam was born and raised in Seoul. His parents were directors of documentaries and dramas. When he was young, his temper (and naivete) would trap him into numerous fights; in response, he took up tae kwon do and worked up to a black belt. He grew up to be a barrel-chested six-footer with none of the physical grace one expects from a martial arts practitioner. Also he kept his intelligence in the background, preferring to keep an amiable but clueless persona up front. The sum effect was that of a friendly, bumbling strongman who had no clue as to what was going on around him. But he still had that temper. Even as an adult in America he would get into brawls in public places, usually breaking his own glasses in the process, along with innocently bystanding furniture. He had an excess of energy which he had learned to channel to a certain extent into the solution of thirty-page-long quantum mechanics problem sets through nights thick with cigarette smoke and eyes zoned with caffein, or into driving 800 miles on a weekend trip to have lunch with an infatuation. But his combination of an easy trust in people and the quicksilver anger which materialized upon betrayal would unexpectedly overwhelm him into physical violence.

His parents had divorced when he was in high school. He was tender toward his mother and his younger sister and brother. But it was a family which was refreshingly libertarian, especially for a Korean one. I was quite envious of Nam's relationship with his mother. They were not financially dependent on each other and related to each other as friends. In fact, I was quite attracted to his mother; even though she had to work in a lawyer's office to support herself and her younger children, she still carried the aura of an auteur and the serene balance of mind which sometimes follows a long-needed divorce. Nam and I joked about this, especially since he was infatuated with my married sister.

I never met Nam's father. Whenever the father was mentioned, Nam's voice would change--a slight tremolo would enter it, just like it did before he was about to punch a suddenly hateful face. For him, his father = the lowest form of life.

He also held a peculiar disdain for Korean-Americans who were too mainstream (read "white") American. One time he whipped out his lighter as we were walking around campus and starting setting fire to campaign posters of an Austin Kim who was running for a seat on the student council. "Fucking politician," he muttered. I never received any more explanation than that.

Sometimes it seemed strange to me that he liked to hang out with me. After all I was a half-breed who spoke Japanese but not Korean, who had a white girlfriend, who was generally lazy and low on energy and moral indignation. Perhaps he was intrigued by my rootlessness and lack of identity. Sometimes he tried to get my Korean "instincts" to surface and take over--attempts which were so transparent that I had to laugh. Why did I hang out with him? Well, let's just say that one was rarely bored in Nam's presence.

During my two years in Africa, Nam and I did not keep in close touch. Somehow, though, we both ended up in grad school at Cornell. It was not such a long time apart, but we had both changed substantially. Nam Hoon (meaning "honor to the South") Kim had consciously returned to his roots. He went back to Korea to, well, he said this himself, look for a wife (and he did find one eventually). He had decided that life, after all, was about having a family (with Confucian family values, no less). He even started considering going to law school (after all, a PhD in physics only provides for a middling economic status), which was quite an irony considering his past experience with lawyers. I, on the other hand, had become even more rootless and unfamilylike. Even though living in the same town, we drifted apart and lost contact.

But now, back to the BMW.

During the summer of '85 I wrote software in Moenchengladbach and Nam smashed atoms at CERN. One day he decided to visit me and hopped on a train, lab notebook in hand. He was working on some equations when, coincidentally, another physicist sat down beside him and began asking him about the equations. So Nam gave him the notebook and received a map in exchange. They began talking after a while, then the stranger left the train. Nam then dozed off. When he woke up he was in Germany; the map was still on his lap. I believe this sort of departure from the normal minimum of attentive behavior could only have happened with two physicists intent on discussing their work.

Tragically, the lab notebook not only contained his precious equations, but also his passport and my phone number (apparently the border control never came around to wake him up). When he arrived in Moenchengladbach he went to the phone booth to call his roommate at CERN, but realized he did not have any change. He went to the kiosk, but the vendor refused to simply make change. Since he was starving anyway, he bought a candy bar (a "Hanuta" bar, says Nam) to obtain the necessary coins.

He makes the call. All incoming calls to CERN go through a central switchboard operator who speaks French and who refuses to acknowledge even the most rudimentary requests in English. Nam does not know French. Result: the operator hangs up.

Meanwhile Nam has eaten the Hanuta bar and goes back to the kiosk. He buys another and makes the call. Same operator, same result. Another Hanuta bar scarfed in desperate hunger and anger.

The process goes through one more cycle. ("I never want to look at a FUCKING HANUTA BAR again." I don't know why he didn't buy something else. I guess he was somewhat panicked.) The fourth time around he yells immediately into the phone: "I'M GOING TO KILL YOU IF YOU DON'T CONNECT ME!" Miraculously the operator suddenly understood certain English phrases.

In the end Nam always lucks out; otherwise, he would never have lived to adulthood. In this case, his roommate was home and was able to find my phone number. The other physicist had turned in the notebook and passport at the train station, so Nam was able to get them back a few days later. Then he looked through the classifieds and bought a car. That was the summer when the dollar peaked against European currencies, and everything seemed like a steal. A used Beemer for $300. Nam, self-satisfied, drove it back to Geneva.

At the end of the summer I traveled around Europe. Inevitably I went to Geneva, phoning Nam in advance to pick me up at the train station. By this time I had known him long enough that I was unperturbed not to find him upon my arrival. I take a bus to CERN and have him paged by the guard. He comes out grinning, that one eyebrow twitching uncontrollably: "Jesus, I thought you said 'p.m.,' not 'a.m.'" He immediately gets excited and wants to leave right away; we had talked about driving to Venice.

We get into his car to drive to the bank for money, but he realizes that it is a Swiss holiday. Meanwhile I had noticed that the car still had the special oval license plate which is only for temporary, border-crossing use. Nam had--surprise!--neglected to register the car in Switzerland. But he gets this idea, which, somehow, didn't seem so bad at the time: we could drive across the border into France and come right back to see what would happen.

Going into France was no problem--no papers checked, just a routine wave-through. But upon return, the Swiss border guard was stereotypically meticulous. First he asked for passports: I get my U.S. passport back after a cursory glance; Nam's R.O.K. passport gets a more careful examination. And, sure enough, he spouts a few words in French, finger jabbing at an open page: NAM'S VISA HAD EXPIRED. After that he goes through the car papers and finds the expired registration; not only that, the insurance had also expired.

I don't remember exactly how we reacted. Did I take Nam to task for being a caricature of himself? Did Nam threaten to kill the official with a tae kwon do roundhouse kick to the head (for not speaking English)? Did passing border-crossers turn their heads to a barrage of "fuck"s and "shit"s emanating from the little red BMW? I don't recall. What I do remember clearly is Nam saying, "You know, I don't think Italy requires a visa for Koreans."

I remind you that we were on the way to the (closed) bank to get money; therefore, Nam did not have (1) money, (2) a toothbrush, (3) change of clothes, or any other items usually associated with traveling. But after consulting the map we decided Italy was close enough that we had nothing to lose by trying to cross its border.

This is what happened:

i. The closest border crossing turns out to be a toll tunnel. We have neither the French francs nor the Italian lires required for passage.

ii. We make a detour (a double detour after encountering a closed road) through a remote mountain pass, and...success! It is quite late, and the border guards have gone home for the night. The road was beautifully illuminated by the light of the near-full moon reflecting from the snow-covered mountainsides.

iii. As soon as we emerge from the Alps, we unknowingly enter a toll road. There is a comically tense moment as we bribe the Italian toll booth operator with Swiss francs. Quickly we make our exit and pull off to the side to get some sleep.

iv. In the morning we find a bank, change money, and eat freshly fried fish fillets, still sizzling with oil, for breakfast. Thoroughly rejuvenated in outlook, we head straight toward Venice.

This brings us back to the beginning of this story. After a few hours of very pleasant driving, in fine northern Italian summer weather and through a countryside which reminded us of California, the engine seized, ceased, and desisted with a very loud noise and much smoke.

We never found out what happened to the Beemer. I imagine some enterprising youngster butchered it and sold the prime cuts.

After a long hour of sticking our thumbs out and looking conspicuously foreign, we were finally picked up by three Napolianos in a tiny Citroen. Through much hand-waving we let it be known that we would chip in for gas. The five of us packed ourselves in and buzzed away eastward.

Okay, what next? you might ask. I was in a similar mindset by this time. This is probably why when we stopped at a cafe and one of our traveling companions motioned he had to go back to the car I surreptitiously followed him. In this case my paranoia was rewarded with the sight of my backpack being rifled by our Napolitan friend. His first response to our confrontation was ludicrous: he pulled out his wallet and pointed at a portrait of the Virgin Mary, then clasped at his heart as if to say that he was in the midst of committing an act of extreme piety and Christian brotherliness. But when it became clear that Nam and I were departing immediately from their midst, all three of them started cursing at us and even threw in a few choice English phrases like "motherfucker." Fortunately they did not come after us. Nam was more than ready to crack open a few eggs. Although landing in an Italian jail for assault would have made for a more dramatic twist to this story, there are limits to what seems funny in a picaresque narrative if you have to live through it.

In the parking lot we convince a milquetoast delivery van driver, who is eating a sandwich, to give us a ride to the nearest train station. He speaks a little English. When we tell him of our hitchhiking misadventure, he wags his index finger emphatically left-right, left-right: "In the south, beautiful land. People, no good. People, no good"

In Venice we find a place to stay, buy a large jug of cheap red wine, and head over to the San Marco plaza to drink it. The alcohol amplifies the absurdity of the past two days. We talk and laugh and get plastered. Nam thinks the overhead mercury vapor lamp is the moon. We decide to call it a night.

Nam in Venice.

In the morning I see him with that grin of his and realize that something had happened. "Oh nothing much. When I came in last night I just flopped on the nearest bed and there was a girl already there. She didn't scream or anything but it was kinda embarrassing." The next night we were in the same room. In the middle of the night, Nam's bed abruptly broke and he landed on the floor. "Now THAT wasn't my fault."

As I said, however, Nam gets lucky in the end. On our return to Switzerland, Nam's passport was only casually examined, and we made it to Geneva just in time to catch the last bus to CERN.

I hear Nam married a nice Korean girl. I can't help but wonder whether his born-again traditionalism and Confucian family values will straitjacket his clueless and once-boundless energy. But somehow I suspect that one day I will see a familiar face in a newswire photo under the caption, "PARENT STARTS BRAWL AT PTA MEETING."

April 11, 1994