Case Study 3: Lewiston New American Sustainable Agriculture Project (NASAP)

|

Somali Bantu farmers sell their produce at the weekly market in Lewiston Source: Heifer International publication |

Introduction

The Bantu secondary migration to Lewiston, Maine came to national attention in 2002 when the Lewiston Sun Journal published a letter from the mayor asking Somalis to stop sending for their friends and families. He pleaded that the city was “maxed out financially, physically, and emotionally.”<1> This letter piqued the attention of neo-Nazi hate organizations. A few months after the letter was published, the World Church of the Creator held a rally in Lewiston to recruit new members. However, local politicians, activists, and religious groups strategically planned a diversity rally on the same date and were successful in squashing the momentum of hate rally. Though the mayor did not attend either rally and never formally apologized, he did meet with the Somalis and clarified that his concerns were economically, not racially, motivated. Ultimately, the conflict diffused.

Lewiston, the second largest city in the Maine, has an industrial boom-bust history that is similar to that of Utica, New York. In the late 1800s, the textile and shoe manufacturing industries attracted droves of Irish and French Canadians to the town. When these industries migrated south, Lewiston joined the rustbelt; the population declined, poverty increased, and houses went vacant.

As in Utica, the refugee population is seen as a key component in Lewiston’s urban renewal. The first Somali family arrived in 2001. Officials estimated in 2006 that the Somali population had grown to nearly 3,000, making them the dominant non-white ethnic group among the town’s 36,000.<2>

Amy Carrington, the farm coordinator of the Lewiston Sustainable Agricultural Project (NASAP), came to Maine after spending three years working for the Tufts New Entry Sustainable Farming Project (NESFP) in Lowell, Massachusetts. There are components of the NASAP that look very similar to the NESFP. However, the population served and context drove Carrington to adapt the model, particularly in terms of program evaluation.

Amy Carrington and I spoke for about an hour about NASAP, her experience growing up and working in Lowell, and how she interprets Lewiston and the Somali Bantu farmers.

|

Somali Bantu farmers. Source: Heifer International publication |

Project Overview

Started in 2002, a seven-acre farm supports 12 to 20 Lewiston immigrant farmers and their families. Through a one-year “Explorer” apprentice program new farmers are given quarter-acre training sites. If they are successful in the “Explorer” program then NASAP helps them find larger tracts of land to expand their operations. All farmers have the option of taking their produce to the downtown farmers market. They also take business development and math courses at Lewiston Adult Education.

Currently, Lewiston NASAP farmers are mostly Somali Bantu women who were subsistence farmers in their home country. As women from a minority tribe, female Bantu lack education and employment prospects in the U.S. The project is a good fit for these women because it takes advantage of the skills they have and also allows them to bring their children to the jobsite. For most of the NASAP farmers, the farm is first a source of food for self and community. Secondarily, it is a possible means to a livelihood.<3>

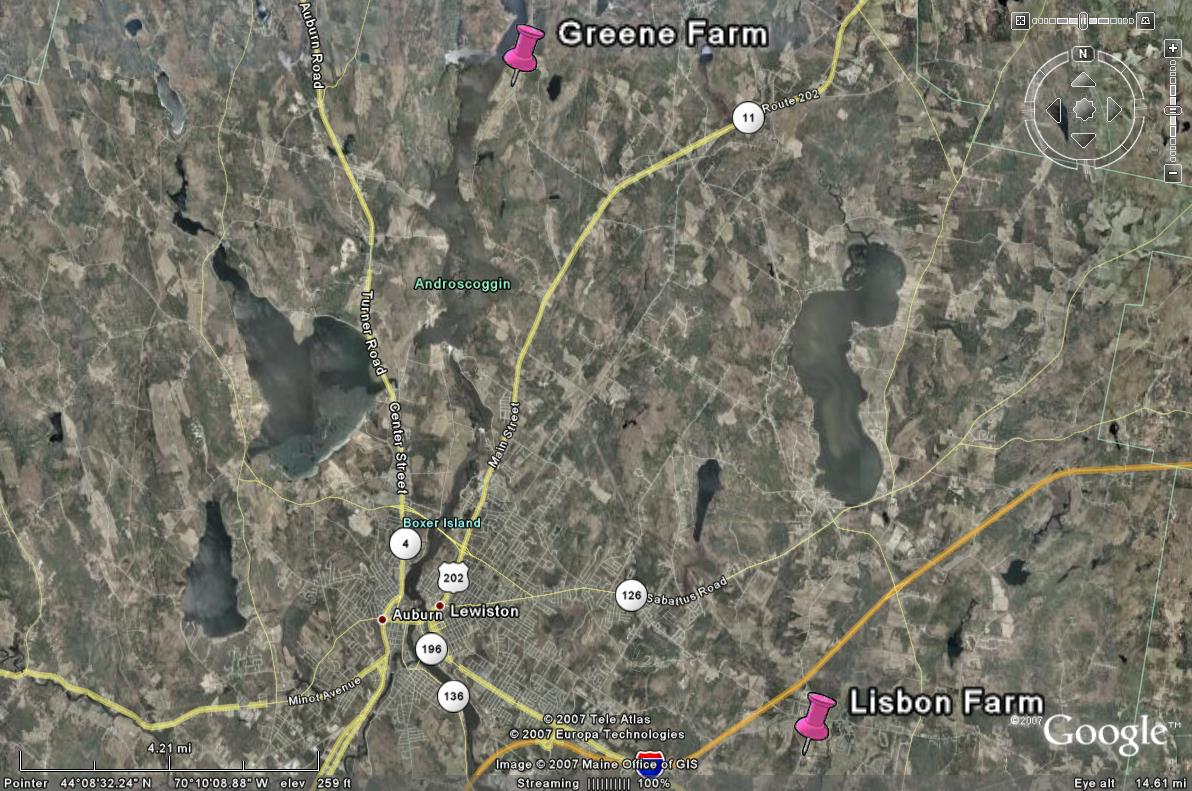

The program was initiated by Coastal Enterprises, Inc, (CEI), a local CDC. NASAP works in collaboration with the National Immigrant Farming Initiative (NIFI) which in turn is supported by Heifer International. Land is leased from local farmer, Bob Packard. The training farm is in Greene, Maine, nine miles from downtown Lewiston. Farmers live in the city. Transportation to and from the farm is one of the program’s challenges.

Project |

Initiated By |

Serves |

Primary Goal |

Delivered Benefits |

Lewiston New American Sustainable Ag Project |

CDC |

Immigrants, Asylees and Refugees |

Train immigrants to farm in the U.S. |

Fresh Food |

|

Evaluating Success

Ibrahim Dahab, from Sudan, started a Halal meat business with technical assistance from NASAP and matched funds from his CEI Individual Development Account (IDA). NASAP helped him with land, transport, capital, and start up supplies. <4> His success is the kind of “up from the bootstraps” story that the greater society tends to celebrate.

However, most farmers in these training programs do not achieve the level of independence that Dahab has. There are many barriers to becoming a self-sustained agricultural entrepreneur. Besides the challenge of learning cultivation methods for a new eco-system, farmers must learn how to compete in an American market. They must overcome language, transport, and cultural differences.

For this reason, the success of NASAP must be measured according to non-market indicators. The meaning of “sustainability” in this case is not “financial sustainability.” Most farmers have to work other jobs and/or collect public benefits.

“Success must be measured on an individual basis. If a person can identify goals and work towards them, then they are moving toward sustainability.”

—Amy Carrington

Goals change over time. Perhaps the first is to feed one’s family, and the second is to grow affordable, culturally appropriate food for the community. After that, goals differ from person to person. For some, the farm business will be a match, but for many it will be an educational process.

=====

<2> Ann S. Kim an Josie Huang, “Maine Remains ‘Whitest State,’” Morning Sentinel, August 5, 2006

<3> Amy Carrington, Interview by author. Cambridge, MA, November 14, 2007.

<4> “The New American Sustainable Agriculture,” Coastal Enterprises Inc. http://www.ceimaine.org/content/view/115/164/ (accessed December 8, 2007)