Discussion The unique cultural and political forces that so violently shaped the city of Berlin during the twentieth century also played a critical role in creating the conditions for the experiment in urban ecology that took place at the Gleisdreieck and Sudgelande areas. Over the course of several decades, the once bustling nodes of rail infrastructure have undergone a re-wildering process in which gravel railbeds and crumbling brick walls created the new substrate on which a hybrid urban successional process has occurred. With the development of the Sudgelande Nature-Park and the soon-to-be-constructed Gleisdreieck park, new layers of use and experience will be overlaid with the ongoing cultural and ecological process evident in the landscape. Rather than seeking to recreate an idealized or romanticized vignette of nature in the heart of the city, the designs for these landscapes recognize the urbanity of the site and seek to preserve, not only the frozen relics of the past, but the dynamic ecological and cultural processes by which the landscapes unique character was formed. Had the Sudgelande and Gleisdreieck sites been evaluated according to a conventional notion of “naturalness” retrospectively defined by comparison to historical ecological communities, they would have been found to be deeply lacking. Deeply marked by their industrial and urban histories, the sites have been dramatically altered from the buildings and machines that litter their grounds to the very chemistry of their soils. The designers of Sudgelande and Gleisdreick have found value in a different kind of natural-ness on the sites. The natural phenomena and systems that are found at these two sites, and in countless cities around the world, is a nature defined not retrospectively, but prospectively.(Kowarik, 17) Rather than comparing the landscape to an historical ideal, a prospective view of nature looks to the ongoing processes on the site. Looking at landscape with a prospective view of nature allows for the valuation of processes over static images. In such a landscape the building of soil health and the slow process of successional change from grassland to woodland join the specimen tree and the ornamental flowering plants as the object of appreciation. In the dynamic landscape of the contemporary city, such a prospective view of nature that allows for a new understanding of the nature of the fourth type is especially useful. According to Stefan Korner, “urban-industrial woodlands are assessed as natural to the extent that they are free from direct, irreversible human impacts and that they have reached a high-level of self-regulation.” (Kowarik, 21)

|

Abandoned rails and active walking paths at the Sudgelande Nature -Park (Source: Google Earth, Accessed 1/10/08) |

At Sudgelande and Gleisdreieck, objects of cultural production too are treated as part of ongoing natural processes. Likewise, alterations and interventions made in the creation of the parks appear to have been designed according to a prospectively-defined concept of “culture” that merges with the prospective notions of “nature”. Such an approach has created a landscape in which neither cultural nor natural objects are preserved as monuments. Rather, the ecological and cultural processes of production and decay are highlighted as ongoing dynamic forces. The emergence of the unique landscapes at Gleisdreieck and Sudgeland was made possible by a combination of cultural conditions: political, social, and economic turbulence in an urban context. If the last several decades are any indication, both urbanization and cultural/political turbulence will play an even more formative part in defining the next century than they did in the 20th century. As such, Sudgelande and Gleisdreick might serve as interesting starting points for considering how urban landscapes can increase the richness of urban life by bringing urban dwellers into contact with the cultural and ecological processes that define the life of the city. Can we imagine critically and thoughtfully-designed interventions in the no-man’s land of the U.S. – Mexico border, the post industrial wastelands of the Pennsylvania, the decaying neighborhoods of Baltimore or Detroit, or the highway medians and verges throughout the country? Taking cues from these projects in Berlin might encouraage designers to treat these ‘backlands’ as the rich and complex landscapes that they are and create interventions that help to clarify and visualize the ongoing natural and cultural forces that have shaped the lands. |

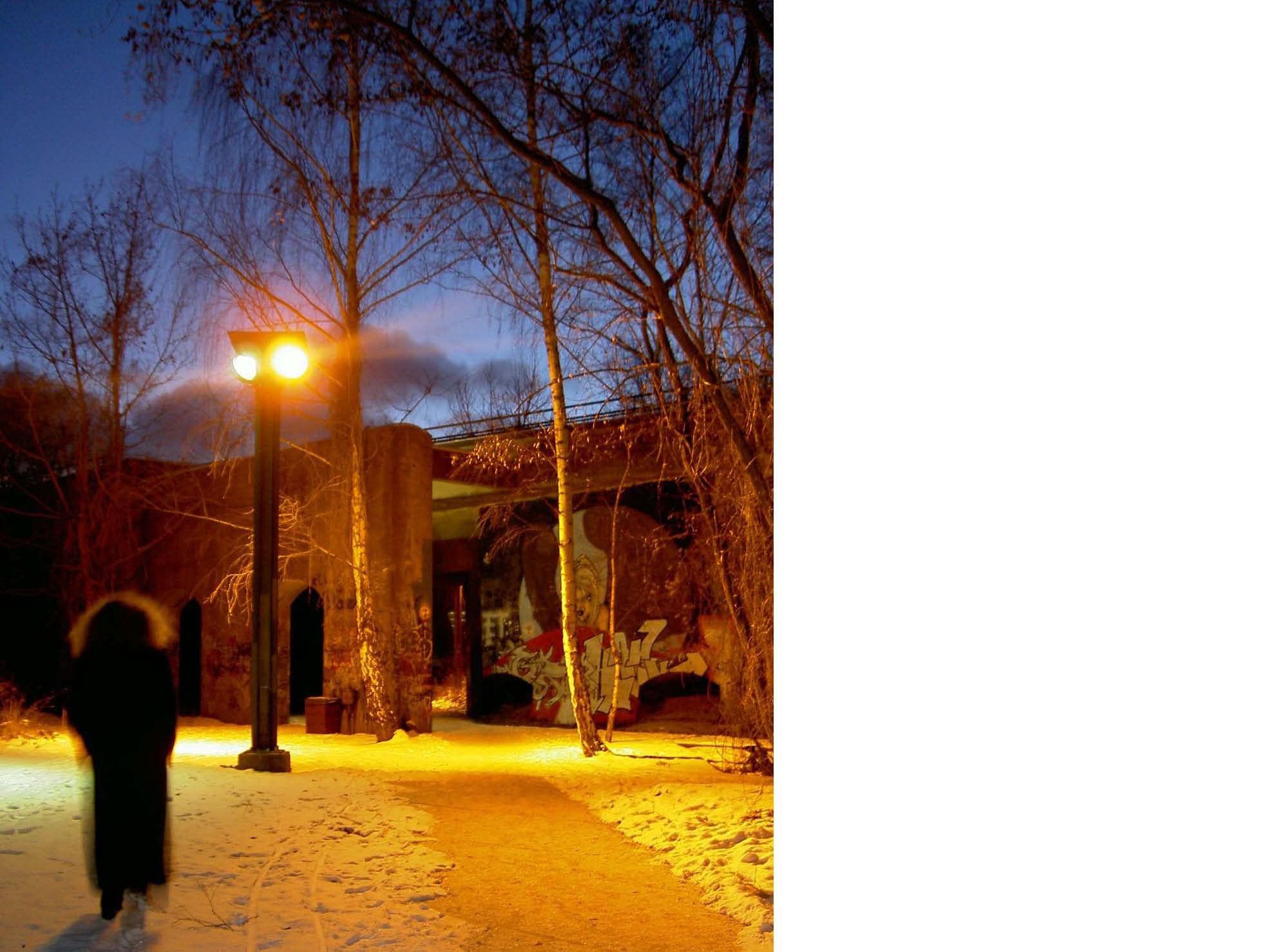

(Source: Panoramio, Berlin - Eingang zum Schöneberger Südgelände, bufonto, Accessed 1/10/08) |

| Sources and Further Information |

"Wild Urban Woodlands: Towards a Conceptual Framework". Ingo Kowarik in Wild Urban Woodlands: New Perspectives on Urban Forestry. Kowarik, Ingo, and Stefan Korner, eds. Berlin: Springer, 2005. |