Spring 2002

In a conversation with soundings, Ellen Harris discusses her new work Handel as Orpheus: Voice and Desire in the Chamber Cantatas.

![]()

![]()

Soundings is published by the Dean's Office of the

School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences at MIT

Editor:

Jeffrey L. Cruikshank

Editorial Assistance:

Sue Mannett

Ellen Salvi

Layout and Art Direction:

Conquest

Design, Inc.

Design:

MIT

Publishing Services Bureau

Online Publishing:

Feisty Design

“I would argue that Handel is one of the first composers to bring silence into the fabric of the music.”

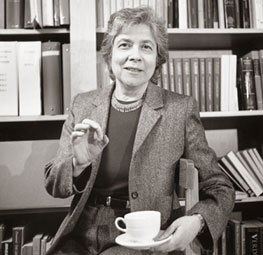

Professor Ellen Harris's new work is raising eyebrows in the musicology community.

Photo: Graham G. Ramsay.

Breaking icons, lyrically

Ellen T. Harris—interviewed here by contributing editor Orna Feldman—is Class of 1949 Professor of Music and head of the Music and Theater Arts Section. An eminent Handel scholar—she has written two books on the composer and another on Henry Purcell's Dido and Aeneas—Harris is also distinguished as an opera singer, having performed roles in Mozart, Puccini, Massenet, Gilbert and Sullivan, and others. She also has been involved in arts policy and education; from 1989 to 1995, she served as the first Associate Provost for the Arts at MIT, a post she took following a tenure as professor and chair of the music department at the University of Chicago. Recently she served as musical consultant to the Santa Fe Opera. Harris is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Her recently published Handel as Orpheus: Voice and Desire in the Chamber Cantatas (Harvard University Press, 2001) explores the homosexual subtext of Handel's cantatas.

The title of your book compares Handel to Orpheus. Why did you choose Orpheus as the object of comparison?

Because in the only cantata in which Handel was named—and there are more than 100 of them—he is compared to Orpheus. Mythologically, Orpheus is often a symbol of a great musician. The myth is quite interesting, because after Orpheus goes down to hell to win back his deceased wife by singing, he fails the human test: he looks back at her before they reach the earth and loses her forever. Most musical adaptations of this story end right about there, or tack on a happy ending where Apollo raises Orpheus up into the heavens as a constellation. But according to the myth as it was told in the classical era, Orpheus gave up all women, urged other men to give up women, and said he would love only other men. This little-known part of the Orpheus myth seemed particularly important to the cantata, because I had already realized that a number of the cantata texts were related to same-sex love and Handel's Italian and early English patrons had been associated with same-sex love. The cantatas, also, were the only music not published in Handel's lifetime; they were private music written for private patrons.

When you piece it all together, what conclusions do you draw?

It is very clear that in writing his cantatas Handel was working toward satisfying his patrons' desires, as an artist would. He lived in a context where same-sex love was a very real part of the atmosphere. The texts are all about desire, longing and love—sometimes heterosexual and sometimes not, since the patrons frequently were married, sometimes had children, and sometimes had same-sex relationships as well. That was relatively common among the aristocracy at the time, and much less understandable to us, where we try to divide sexuality and say, "You're one or the other." The term 'homosexual' had no meaning in the 18th century.

How was homosexuality viewed at the time?

Human love and human sexuality encompassed both same-sex love and heterosexual love. People didn't identify themselves as heterosexual or homosexual. People had intimate relations. Some had them with both sexes, some didn't.

How does this fit in with Handel and his music?

What I've tried to do by looking at the sexual context of the period is learn more about the cantatas. There are 100 of these works and there's never been an in-depth study of them, which is really quite astonishing. By looking at the sexuality of the period we really do better understand the music and Handel's development as a composer. For example, we understand changes he made in his style, which have to do with the texts and the way sexuality is treated in the texts—a kind of distancing that occurs in the music after a few years. Originally the music was enormously passionate and heartfelt; after a while it develops a façade, a classicizing elegance.

Harris: participating in the creation of music is important to a deeper understanding of how music works "from the inside out."

Photo: Graham G. Ramsay.

In your book you discuss the role of silence in same-sex love. Can you elaborate?

The cantata texts are constantly talking about a 'love that I cannot speak about,' 'a love I must keep to myself.' That silence then moves from the text into the music. Suddenly there are gaping silences—the whole music stops, as if the singer can't go on. That's unusual even for music of the time. So I would argue that Handel is one of the first composers to bring silence into the fabric of the music. The need for silence in both illicit love and diplomacy must have been clear to him, and not surprisingly, this life lesson found its way into his music. And one of the reasons is these texts.

What kind of response has your book received?

It's not been reviewed anywhere yet, but it has been reported on in London. It began with an article in the Sunday Telegraph, saying that I say Handel is gay, all his patrons are gay, and the silence in his music means being gay—as if silence was equivalent with being gay. People have had a heyday with this.

What kind of a response do you expect from the musicology community?

Mixed. There are people who simply cannot accept the placement of Handel into a society in which same-sex love was a significant part—primarily because he's the composer of Messiah and an iconic image is being challenged. Other people might like the book for the wrong reasons—because they want that piece of divinity to be associated with homosexuality. For me, the book is important because it explores and makes available a huge repertoire of Handel's music that no one has listened to.

You have great familiarity not only with Handel, but with the 18th century in general. Do you live there in your mind?

I do live in the 18th century in very bizarre ways. I am one of the few people I know who does not own a cell phone. I believe it's possible to be out of touch with people for a while and that's not a bad thing. When Mozart was away from his family in the 18th century, he'd be away for months, sometimes years at a time. If someone passed away, he would find out sometimes months after they passed away. To be out of touch raises a relationship above the level of the mundane. Communication needs to be more important than saying, "Now I'm crossing the street." The kinds of communication people had with one another in the 18th century—cell phone and e-mail correspondence can't hold a candle to it.

In your book you say that a Mrs. Delaney, a Handel contemporary, taught you how to write about the 18th century.

She is the one who said, "Oh, by the way, I almost forgot to tell you. As you know, my Lord keeps a male seraglio." You read that and you go, "Whoa! What did she say?" She does not treat this as unusual—it's all very straightforward. It seems to me that we've lost a little bit of that today. What's happened to us that the mere mention of same-sex love can make people have the kind of reaction they've had to my book? It's no longer a capital offense to have a same-sex relationship, so some improvement has occurred. But the issue of sexuality is still fraught.

What would you like it to be?

I would like people to recognize that love for another human is a very special thing, regardless of who the other human is. In homosexuality as in heterosexuality, there's a whole range of desire that extends from love and longing to sexual acts. We are sometimes so terrified of same-sex sexual relationships that we've lost out on the same-sex love as well. That strikes me as a huge loss.

What role does performance play in your scholarship?

Making music is a really special gift, and to be able to make music sound, especially as a scholar, is enormously important. The experience of actually participating in the creation of the sounds that Handel conceived is important to understanding how the music works from the inside out.

What about the scholarship part?

The way I sing and perform demands thinking about the music and making decisions about what the music means and how one should make the notes sound. Those two things are inseparable—making the music sound and understanding the music.

Let's segue to you as a performer. In addition to your operatic roles, you've been referred to as NationalAnthem.com. Why is that?

I came to MIT in 1989 and since then I have sung the national anthem in all but three MIT graduations. I've also sung the national anthem at Fenway, in honor of President Vest's 50th birthday. And that was fun because I sang it live. The Red Sox didn't want me to—they want everyone to record it ahead of time and lip-sync it—but I told them, "I don't lip-sync. If you want me to record it, fine. But then I won't go out on the field. Or I'll go out on the field and sing it live. You choose." So they made me come down and audition in Fenway, which was a hoot.

Do you teach music differently here than at other places?

Yes. I lead through the music, not through history. I don't say, "Schubert wrote X number of songs and his dates were such-and-such" and then move on to the music. I sit down, play a song and sing it, and then begin taking the song apart. I try to talk about compositional tools: "What would happen if you did it differently? If you changed this cadence? If the modulation went to a different key or a different meter?" Composers have choices. Why is one preferable to another? You can actually get at the music through a toolbox exercise and then lead from that into history. That approach works particularly well with MIT students.

![]()

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Institute of Technology