“The complexity of the urban ecosystem defies understanding, but the dangers of not comprehending are frightening.” -Anne Whiston Spirn

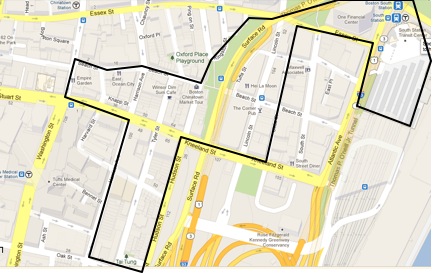

Fig. 1: Map of Boston taken on February 18, 2013 from maps.google.com

Fig. 1: Map of Boston taken on February 18, 2013 from maps.google.com

Thousands of people move through the South Station and Chinatown area each day, paying visits to doctors at neighboring Tufts Medical center, eating at Chinese restaurants, dealing with business at One Financial Center, or heading to another city via the I-90 interstate highway or an Amtrak train. Here, city planners, architects and engineers have fabricated a diverse urban landscape, marked by a variety of different landmarks and infrastructures. Upon first glimpse, it is difficult to see how nature has played a role in the development of this part of Boston, if at all. Indeed, upon further investigation of both the site as it stands today and its environmental history, it is clear that those who have built upon this area have more often tried to overcome its natural features and processes than work in harmony with nature’s forces, with important repercussions manifest in the site today.

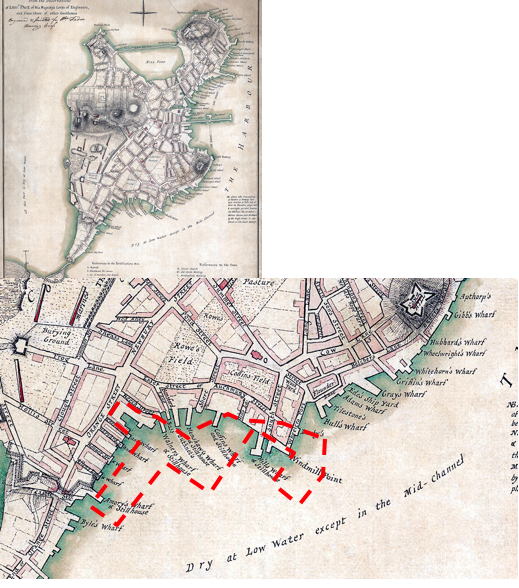

The environment of this site has been shaped by man’s influence since the beginning of its existence. When Boston’s first settlers arrived in 1630, most of this area did not exist –in its place were marshland and open water. Shown here is a map depicting Boston as it was in 1775, a mere fraction of the peninsula it is today. The approximate location of my site is marked on the zoomed in portion of the map by the red dotted line.

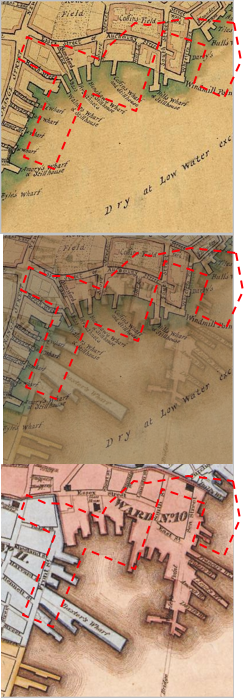

One can see that by 1775, Boston’s settlers had already built many wharves and roads along the peninsula’s shoreline, leaving no trace of the undulations of a natural shoreline in the map above. As the years went on, these wharves were expanded, as shown in the progression of images to the left depicting how the map of this area of Boston changed from 1775 to 1826. From 1826 to 1840, much more marshland in the bay was filled in with wood pilings, debris, and other organic material, allowing my site to develop in the location it is in today. Rather than expanding Boston into inner, naturally formed lands beyond the peninsula, the settler’s chose to defy nature’s demarcations, representing the beginning of man’s quest to change the natural form of the area to suit his needs. However, traces of the original topography of the area can still be seen today: standing at the intersection of South Street and Essex Street, one can see an obvious incline in the land downwards towards the Leather District in the south. Conversely, one can see an upward incline towards the Financial District to the north, as indicated by the arrow in the image to the left below. This incline is even more obvious when one takes a look at the slanted bases of the buildings along South Street, shown in the image to the right below. This area marks the boundary of where the filled land begins. Perhaps the previous structures built here compressed the less dense material of the filled land over time, creating an incline that the constructors of the current buildings have had to accomodate. Or, perhaps, the incline is naturally occuring, a reminder of the gentle sloping of a beach that could've existed here centuries ago.

The buildings of Chinatown and the Leather District, south of Essex Street, are also significantly shorter than the skyscrapers of Downtown Crossing and the Financial District to the north. Perhaps this height reduction reflects a conscious effort on the part of city planners to build smaller, lighter structures to lessen the load on less stable filled land. All of these accommodating measures are necessary to allow this cityscape to exist upon the artificial land that man has impressed upon the natural topography of this area.

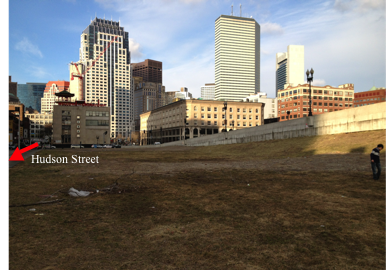

No notable topographical features, such as hills or rivers, distinguish this flat region of filled land. As such, it seems the region’s natural topography did not inform the way streets and structures developed in this region. Rather, it is primarily large, man-made infrastructural developments that have shaped the way peripheral areas have been laid out, and the way these areas interact with ongoing natural processes. Some of these structures have taken many natural processes into consideration, allowing them to work in harmony with natural forces towards the benefit of inhabitants. For example, the construction of the I-93 highway has significantly influenced its surrounding landscape. The surrounding area along Hudson Street, once occupied by thriving neighborhood centers, was cleared to make way for the planned highway in the 1950s.

Now, a large expanse of open grassland neighbors the highway, sloping upwards to meet the elevated structure, as shown in the image above. The lack of tall buildings surrounding this highway has prevented a ‘downtown canyon’ where air pollution can be trapped in inversions, as described in The Granite Garden, from being created. However, although the field itself is barren, its bordering Hudson Street is dotted with tall, sturdy trees growing out of small plots. These trees grow in front of brick houses displaying “keep out of private property” signs, and show no signs of being regularly attended to by local residents. The leftmost image below shows the base of one such tree strewn with trash.

However, it is clear from the tall, webbed branches stretching for sunlight of the tree in the rightmost image above that these trees are doing well, even if only in comparison to the few thin but well cared for young trees growing out of metal grated plots in front of high-end commercial and residential buildings in the Leather District (shown in the image below).

It seems the construction of the highway has unwittingly established favorable conditions for natural processes to help these trees survive. The I-93 would no doubt fall under what Anne Whiston Spirn calls an “arterial street” in her book The Granite Garden: a street that is trafficked by more than 24,000 vehicles a day. She explains that such roads generate zones of air pollution extending 50 meters beyond themselves. The expanse of open field between the highway and the tree-lined sidewalk of Hudson Street just so happens to span around that distance. Thus, noxious vehicle fumes are allowed to disperse before reaching these trees, allowing them access to much needed oxygen. The open space also exposes these trees to plenty of sunlight and rain. In sharp contrast, the trees in the Leather District must struggle for rays of sunshine and wafts of oxygen amidst tall, dense buildings separated by narrow roads congested with vehicles. Though the residents of Hudson Street may not even put half as much effort into caring for their trees as the owners of Leather District properties might, they can benefit from an organic buffer from highway pollution thanks to natural processes. Furthermore, the construction of the underground tunnel portion of the I-90 necessitated a vent structure be built nearby to disperse pollution above street level, next to the traditional gate marking the main entrance of Chinatown along Beach street. A tarpaulin from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts that displays a traditional Chinese painting covers this vent.

A small plot of trees separates it from the I-90. Behind this vent lies a small rectangular courtyard, known to locals as the Mary Soo Hoo or Chinatown Gateway Park. This vent serves an effective shield that prevents the park from being directly adjacent to the road, a location that Spirn describes as being known to contain up to 16 times more lead in its atmosphere than the normal level. It is not hard to imagine this structure offering relief from the sun to visitors of the park during summer, turning it into a “shady haven”. Even on a cold winter day, numerous residents of Chinatown gather to play Chinese checkers in this area, shielded from the easterly wind coming from Fort Point Channel by this vent.

Thus, although this area’s urban planners may not have been very concerned with designing the city around natural, topographical features, they have designed some structures that work cohesively with natural processes towards human benefit.

However, it is clear that in some cases, my site’s urban developers have also ignored natural processes in their efforts to meet human needs. Chinatown is etched with a disorderly web of narrow, winding roads. On most days, these roads are clogged on both sides with parked cars, leaving only a small pathway for slow moving vehicles to trickle through. No trees separate street front restaurants and stores from the line source pollutants of the roadways. Because of this densely packed layout, many businesses can operate within this limited space, at the cost of the comfort of visitors traversing the area by foot alongside belching vehicles. With the high density of traffic in this area, the heat from cooking processes in restaurants, the food waste littering the ground and the heat-absorbing concrete sidewalks and asphalt parking lots in this area, it is not difficult to imagine how it can become hot, smelly and rather unbearable during the summer. The urban heat island effect could potentially be even worse in the neighboring Leather District. Equally narrow, asphalt paved roads and uniformly taller buildings of 5 stories or more define this area. In the summer, these impermeable surfaces could absorb heat and turn the area into a “heat core”, as described in The Granite Garden. The ‘downtown canyons’ formed by the structures in this region could also lead to inversions, where colder, denser air pollution particles are trapped at street level, unable to disperse into the atmosphere above until heated by a midday sun. As a result, residents frequently traversing these roadways could be chronically exposed to a cocktail of toxic air pollutants. In the wintertime, such a setting is equally uncomfortable, if not even more so: the street canyons become dark and gloomy because they are shaded from sunlight by the tall, surrounding buildings. Thus, temperatures in this urban microclimate might be lower than those of neighboring regions, a great drawback in Boston’s infamously chilly winters. Furthermore, unlike Chinatown, blocks in the Leather district are laid on a relatively regular, geometric grid. Unfortunately, the developers of this grid did not seem to take into account the easterly winds coming in from Fort Point Channel, for the east-west running roads run almost exactly parallel to the direction of these winds. The tall, narrow canyons surrounding the roads funnel the wind, strengthening it to the point of enabling it to totally ruin my umbrella on the rainy winter day I walked through the area (when I exited the Leather District into the Chinatown region with shorter buildings and less orderly, straight roads, I could feel wind speed drop dramatically). Furthermore, there seems to be evidence of ground subsidence in some areas of the Leather District, as can be seen in this sunken alleyway between two buildings in the image below.

In The Granite Garden, Spirn elucidates on page 99: “ground subsidence is usually a direct effect of human activities – the pumping of gas, oil and groundwater…building on unconsolidated landfill”. She also mention on page 100: “garbage, rubble, and the wood of old wharves and sunken boats decompose at different rates and may cause subsidence for many years.” The above image seems to show that the middle region of the alleyway is sinking, with the road sloping down from where it borders the buildings flanking it on both sides (the dumpsters are clearly on an incline). This creates a cavity where water can pool up to not only cause inconvenience to people seeking to travel through or park their car, but also potentially erode the paved road and hasten its degradation. Water is more likely to build up on natural surfaces as well, as compacted soils slow down infiltration and drainage. The street trees growing in compacted soil in the Leather district must thus deal with being water logged and oxygen deprived. Thus, in these instances where urban forms have not been constructed with nature in mind, they have been ravaged and undermined by natural processes.

My site also shows how city planners have tried to harness and control natural forms to suit human preferences, to the detriment of the health of the greater urban ecosystem. Barely any pockets of green can be seen on this site, but the greenery that does exist mostly consists of manicured plots whose survivals depend on the humans that created them. On page 174 to 175 of The Granite Garden, Spirn writes: “letting nature take her course is a difficult stance to defend in the city, where most ornamental vegetation is cultivated and survives by virtue of human attention and where intensive use places great stress on natural ecosystems.”

Dewey Plaza, right outside of South Station, is a good example of an area of well-cultivated vegetation: trees growing out of neat square, plots covered by metal gratings dot a granite plaza, flanked on one side by a neat grass lawn. Upon first glance, it may seem like this patch of green breathes natural life into the urban ecosystem – after all, the trees must filter the air, absorb rainwater, and provide shade from the sun in the summer. However, Spirn reveals on page 230 of her book: “the lawn must be mowed, irrigated, raked, and treated with fertilizers and pesticides.” The upkeep of “natural” features in an urban landscape is costly both financially and environmentally. Yet, the developers of financial buildings to the north of my site and residential and commercial ones in the Leather District seem to have this expensive taste –they maintain a few solitary trees in square soil plots, covered by metal gratings, on sidewalks bordering their buildings. These trees are inherently unsustainable – they depend on human support and plenty of other resources to survive. On the other hand, those living in the residential areas of Chinatown seem to be much less willing to devote time and attention to maintaining trees and plants for decorative purposes. However, patches of green can still be found, as evidenced by the images below, which depict the small, sunken courtyard of an apartment enclosure next to Tai Tung Village at the southernmost point of my site.

The ground within this enclosure is more than a meter lower than the land surrounding it on all sides. Despite being strewn with rubble and debris, a tall, evergreen tree has managed to thrive on its soil. Perhaps this is a patch of land that was not filled completely along with the rest of the site, or perhaps the upper layers of pollutant-infested soil were dug up to reveal the more fertile ground below. Whatever the case, natural processes seem to have been allowed to take full reign here in the face of human indifference. As a result, a closed, sustainable micro-ecosystem has been created. However, the overgrown, run-down appearance of this area might not appeal to the discerning, modern property investor, explaining why the values of properties in the rather inhospitable, high maintenance environment of the Leather District far surpass those of properties in residential Chinatown.

Beginning with the filling of the land Chinatown and South Station sit upon, humans have tried to manipulate and shape the landscape of this area to suit their own needs and tastes. However, the success of an urban environment is invariably shaped by its interaction with natural processes. Some man-made endeavors in my site have succeeded in working together with natural processes to better the health of the overall urban ecosystem and that of its denizens, while other developments have either degraded natural resources and conditions or been degraded themselves by natural processes. Overall, it is clear the success of an urban setting hinges upon its ability to withstand and exploit natural processes, and thus it is vital to study the current interactions between our built and natural environment, for as Spirn emphasizes,“The complexity of the urban ecosystem defies understanding, but the dangers of not comprehending are frightening.”

References:

A Plan of The Town of Boston with the Intrenchments of His Majesty’s Forces in 1775, from Observations of Lieut. Page of His Majesty’s Corps of Engineers and from those of other Gentlement. 1775. Boston by Foot. Web. March 4, 2013. <http://bostonbyfoot.org/maps/historic>.

Elkins, James. How to Use Your Eyes. Routledge: New York, NY. 2000: pp. vii-xi, 12-19, 28-33, 170-175.

Map of Boston. 2013. Google Maps. Google. Web. Feb 18, 2013. <https://maps.google.com>.

Maps of Boston from 1775 and 1826. Maps over time. <http://www.mapsovertime.com>.

“Southeast Expressway: Historic Overview.” Boston Roads. N.p. Web. March 4, 2013. <http://www.bostonroads.com/roads/southeast/>.

Spirn, Anne Whiston. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design. Basic Books: New York, 1984.