If I were to tally the total number of times I visited each T station this past school year, South Station would probably come out on top as my most frequented destination, other than Kendall Square. Throughout the school year, I satisfied my craving for Chinese food by sampling the pastries sold by the slew of bakeries in the area with friends, I begun doing most of my grocery shopping at C-mart (which sold ingredients my mom cooked with at an unbeatable price), and I signed up to tutor Grade 5 students every Thursday with the Harvard-Wellesley Chinatown Afterschool program. When this assignment was introduced, I knew I wanted to take the opportunity to further explore and better understand the factors that shaped the fascinating, unique little pocket of Boston I’d become so enamored with.

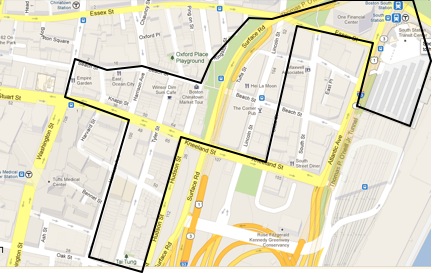

While defining the boundaries of my site, I wanted to include the areas I most frequently walked through. Thus, from the East, my site begins at the South Station Transit Center, which houses one of the exits of the South Station T stop. The center serves as a departure point for buses, the T, as well as Amtrak trains. The site also includes the plaza in front of One Financial Center that I usually walk through, as well as the few blocks of the Leather district that face Surface Road and Chinatown.

Map of Boston taken on February 18, 2013 from maps.google.com

Map of Boston taken on February 18, 2013 from maps.google.com

Then, Chinatown proper is included, bounded on the West by Washington Street. To the South, I’ve also included the residential and community area bounded by Hudson Street and Harrison Avenue, ending at Tai Tung Park along Oak Street. This is the area of Chinatown that the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association’s building, the place we tutor kids at, is located. However, after walking around my site this weekend with the assignment in mind, I realized I’d unwittingly chosen what could be divided into three distinct areas, and the transitional boundaries between them.

First off, South Station and its surroundings seem to represent the southernmost point of Boston’s financial district. When one exits the T out onto the plaza at the intersection between Atlantic Avenue and Summer Street, tall, architecturally stylized office buildings can be seen on all sides. One building at the center of the plaza stands out from the rest: one of its flat faces is adorned by a mural of what seems to be a hooded kit sitting in a cramped position, with his legs curled up. I hope to find out more about the specific corporations that have established office here, as well as the people and purpose behind this large-scale piece of street art.

South Station Plaza. Photo taken on February 19, 2013

South Station Plaza. Photo taken on February 19, 2013

Walking west across Essex Street and then south into the Leather district, one can feel a dramatic change in landscape and atmosphere. Whereas the South Station plaza is expansive and open, buzzing with commuters and vehicles, orderly blocks of tall, industrial, street-shading buildings define the Leather district. Perhaps it was because it was a holiday when I visited on Monday, February 18, but the area was practically deserted. I could see that closed commercial establishments such as salons, restaurants, clothing stores and open spaces for rent filled ground floors, but I couldn’t discern what occupied the multitude of levels above. The Leather District almost seems like the exact opposite of “epitome districts” described by urban planner Grady Clay, a vacant puzzle whose origins and purpose within the context of Boston I’d like to demystify throughout this course (Clay, 1980).

The Leather District. Photo taken on February 19, 2013

The Leather District. Photo taken on February 19, 2013

However, once Chinatown is reached, marked on the east by the gate structure depicted in the picture below, the surroundings come alive again, albeit in a different way than the South Station area. The eastern, Chinatown part of my site is made up of narrow, winding streets lined with cracked, muddy, concrete sidewalks and shops and restaurant, bustling with people of all kinds despite the holiday. The southern stretch of Chinatown in my site is a more residential area, marked by brick sidewalks and much less commuter and vehicle traffic. Though the goods and people in the establishments here were mainly Chinese, many features of the physical structures seemed characteristic of New England or America. For example, the 3-floored brick houses shown below, housing a Chinese welfare center along Kneeland Street, resemble typical New England suburban homes, hinting at the kind of past residents that might have been here before. Furthermore, the motif of street art continues as works of graffiti throughout brick walls in Chinatown.

Residential Area of Chinatown along Kneeland Street. Photo taken on February 19, 2013. .

Residential Area of Chinatown along Kneeland Street. Photo taken on February 19, 2013. .

Judging from my site, Boston seems like a mosaic of small districts, each with its own distinct geographical, structural and cultural features. So how did Chinatown, an area generally inhabited by lower income immigrants, come to exist in such close proximity to the Downtown area and the Financial District? How did the Leather District retain its nondescript, vacant features whilst being surrounded by such vibrant areas on both sides? Did the construction of South Station transit center have any impact on the development of these areas? I look forward to investigating my diverse site to answer these questions and more throughout this semester.

Sources:

Clay, G. (1980). Close-up: How to read the american city. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.