The site that is the focus of this website’s investigation is located in the heart of South Boston, encompassing a portion of the Leather District, South Station, a segment of the I-93 highway and Massachusetts Turnpike, and of course, Chinatown. Its neighboring areas are equally diverse –Downtown Boston lies north of it and the Financial District is to its northeast, while it is flanked on the left by the Theater District (and former Red Light District) and on its right by Fort Point Channel. This site is truly a central, geographic nexus within Boston, where dramatically different zones of the city converge and where citizens of very different social, economic, and ethnic backgrounds rub shoulders each day. Its diversity, and the factors that shaped it over time, will be the focus of the next part of this website’s investigation. How did Chinatown, a part of a city typically known for being low-income and crime-ridden, end up being located in such a central region of Boston, right next to the polished Financial District? Why is it filled with such a diverse range of landmarks, including numerous Chinese restaurants and other commercial establishments, schools, housing complexes, and Tufts Medical Center? Why is the “Leather District”, a dramatically different area of old warehouses being converted into high priced real estate, located right next to Chinatown? The answers to these questions can be found in the history of the evolution of this site. In discovering its historical narrative through studying changing maps over time, it becomes clear that this site is not only a modern geographic nexus, it is also a physical manifestation of the nexus of cultural, economic and political forces that have shaped Boston and the United States as a whole over time.

The Early 1800’s: Puritan Prosperity and Expansion

After the United States colonies gained independence from England in 1776, Boston prospered as a port city actively involved in supporting England against its imperial wars with France in the early late 1700s and early 1800s (Warner Jr. 6). Thus, because the Puritan leadership highly valued the construction of public works and because wharves and seaports were central to Boston’s booming economy, they began to build new ones by filling in land. Shown in Figure 1 are the boundaries of the site on an 1835 map of Boston. Parts of the land of the site have not yet been filled in yet, as its boundaries overlap with many wharves and shorelines.

Figure 1: Map from Plan of Boston comprising a part of Charlestown and Cambridge (Boston: George G. Smith, 1835), from http://www.davidrumsey.com

Figure 1: Map from Plan of Boston comprising a part of Charlestown and Cambridge (Boston: George G. Smith, 1835), from http://www.davidrumsey.com

At this time, the rich still sought to live in the center of the city, as “the suburbs were in every way inferior…the word itself had strong pejorative connotations” (Jackson 16). Thus, even though Figure 1 has no clear indications of distinct landmarks or features, it can be inferred that fairly affluent citizens could have lived in the inner portions of the site perhaps in order to manage shipping based businesses nearby. However, the mercantile prosperity enjoyed by Boston in the early 1800s was soon replaced by the onset of industrialization in the 1840s, ushered in by technological advances and immigrant influxes due to events such as the Irish potato famine of 1850 (Warner Jr. 8).

The Late 1800s: Industrialization turns cities “Inside-Out” (Jackson)

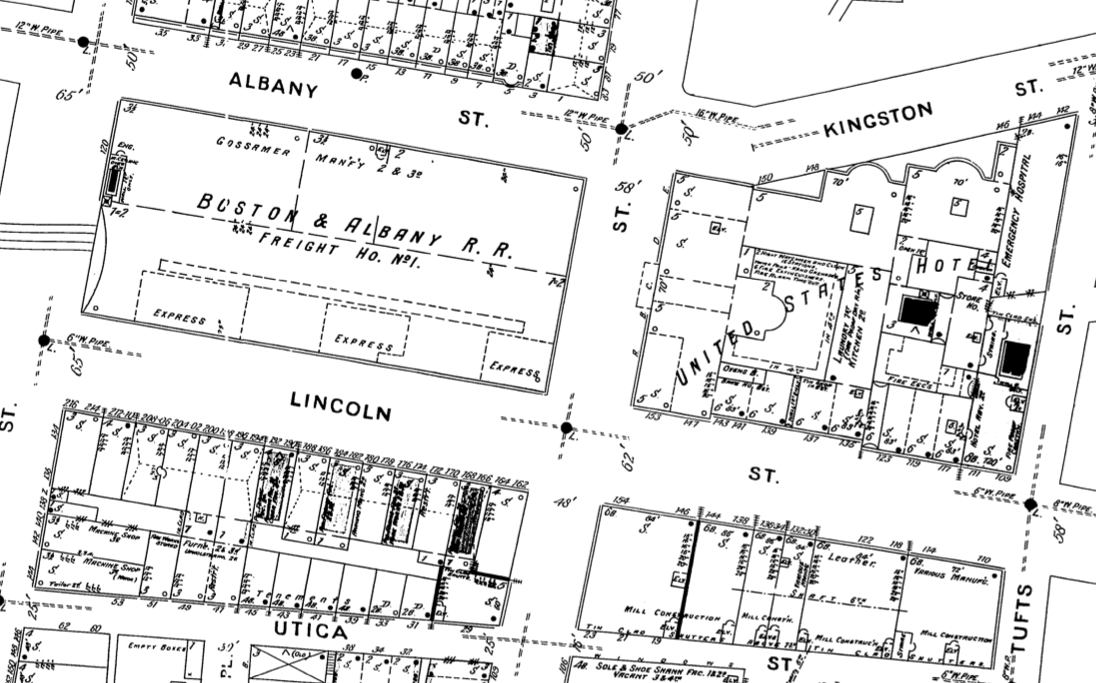

A Sanborn atlas of Boston in 1895 depicts a dramatically different site than what might have existed in 1835. This site is blessed with an extremely convenient geographical location: it has direct access to the Fort Point Channel, an important economic pathway in the era of trading via shipping, as well as to the New York and New England Railroad lines. However, several features of the 1835 map of this site indicate that it was a rather poor area, composed of swathes of residential and commercial establishments.

Figure 2: Map showing portion of what is the Leather District today, from Boston Massachusetts (Cambridge: Sanborn Perris Maps Co. Limited 1895), http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000008.htm?CCSI=254n

Figure 2: Map showing portion of what is the Leather District today, from Boston Massachusetts (Cambridge: Sanborn Perris Maps Co. Limited 1895), http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000008.htm?CCSI=254n

Figure 2 above shows a block of commercial establishments facing Lincoln Street, part of the region known as the Leather District in Boston today. Most of these blocks are made up of neat little rectangular plots marked ‘S’ for stores. However, other labeled commercial establishments include a Leather factory, two machine shops, and a few mill construction places. Beyond the borders of the site lie many more “leather” establishments. These kinds of establishments were probably created in the mid 1800s to support the lucrative textile mills being established in the peripheral regions of Boston (Warner Jr). Another key factor input of the textile industry was also produced nearby: numerous coal sheds dotted the wharves south of the railroad lines where South Station is located today. There was even a wharf named “Coal Wharf”, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Map showing coal storage rooms on wharves near Fort Point Channel and Railways, from Boston Massachusetts (Cambridge: Sanborn Perris Maps Co. Limited 1895), http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000008.htm?CCSI=254n

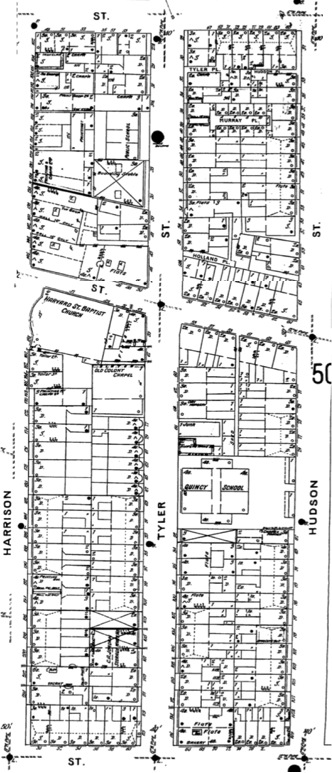

In the beginning chapters of Kenneth Jackson’s book on American suburbanization, Crabgrass Frontier, he depicts “slaughterhouses, leather dressers, and houses of prostitution” as “objectionable businesses” that existed on the peripheries of English cities in the late 1500s (Jackson 16). Thus, the existence of leather producing factories, as well as dirty, polluting coal sheds and a large freight house, in such close proximity to residential areas seems to indicate that the area must have been inhabited by poorer citizens who had less control over what kinds of establishments they lived next to. However, the site seems to be quite organized in terms of making clear distinctions between residential areas and commercial ones. The 4 blocks bounded by Harrison Avenue, Hudson Street, Oak Street and Kneeland street, shown in Figure 4 below, consist of orderly, uniformly sized, small plots marked ‘D’ for single family dwellings.

Figure 4: Map showing predominantly residential area of my site, from Boston Massachusetts (Cambridge: Sanborn Perris Maps Co. Limited 1895), http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000008.htm?CCSI=254n

Interspersed amongst these dwellings are landmarks characteristic of a lived-in neighborhood, such as “Quincy School”, “Old Colony Chapel”, “Harvard St. Baptist Church”, and even a corner bakery. The very small sizes of these residential plots, as well as the dearth of stables and liveries in this area (only 4 can be found in these 4 blocks), seem to point to poorer residents. Another crucial clue is the presence of a building marked ‘F’ for flats, and a few plots labeled ‘Tenements’ (small, rented, low-income flats) near the Leather factories. Back in those times, “respectable American families considered apartment living sexually racy, for busybodies could not monitor the comings and goings of visitors when entranceways did not front the street” (Jackson 90). Thus, the presence of these multi-family homes is a clear indicator of poverty. By examining a 1902 Bromley map of this site, one can also see some foreign names have come to town, as shown in Figure 5 below.

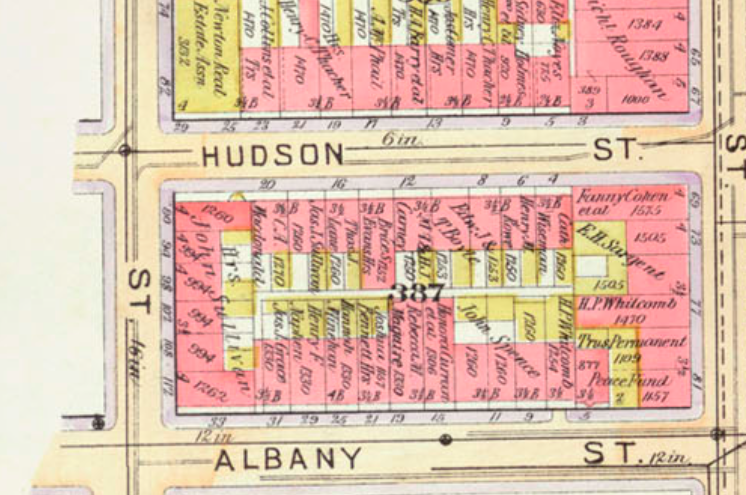

Figure 5: Map showing central area of Chinatown, from Atlas of the City of Boston, Boston Proper and Back Bay, from Actual Surveys and Official Plans (Cambridge: G.W. Bromley & Co. 1902), http://dome.mit.edu/handle/1721.3/47999

Figure 5: Map showing central area of Chinatown, from Atlas of the City of Boston, Boston Proper and Back Bay, from Actual Surveys and Official Plans (Cambridge: G.W. Bromley & Co. 1902), http://dome.mit.edu/handle/1721.3/47999

Landlord surnames such as “Lennihan”, “Maguire”, and “MacDonald” are signs of a burgeoning Irish immigrant population. And although there are no visible indicators of an immigrant Chinese population, one can infer that some young Chinese men might have started to trickle in to this area from the nearby port and railroad, to serve as laborers in railway construction. The development of this centrally located site into a haven for immigrants and working class citizens is in accordance with the national trends of suburbanization at the time, which saw “socially prominent families spreading over the farmlands in the 1870s”, in search of a healthier environment for an idyllic family life to thrive (Jackson 89). This was made possible by the rapid expansion of railroad networks in America in the forty years after 1860, as well as the huge commercial success of an expanding electric trolley or streetcar network, as represented by the dashed line in Figure 5 above. Thus, the development of this site in the late 1800s was very much shaped by the economic trends of the day. The national economic state remained a primary influence, ushering in a different landscape in the site in the early 1900s.

The Early 1900s: Economic Depression allows Immigrants to Settle In

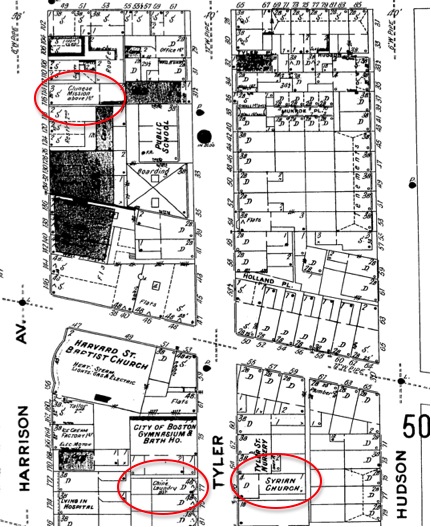

Though the physical structures of the site do not undergo any major changes from 1895 to 1938, subtle differences in a 1938 Sanborn map speak of a dramatically different economic and social climate. The most obvious is a new, noticeable immigrant presence in the site. As can be seen in Figure 6, new establishments such as “Chinese Laundr[ies]” were appearing, along with a “Syrian Church” and “Chinese Mission”.

Figure 6: Map showing immigrant presence in 1938, from Boston Massachusetts (Cambridge: Sanborn Map Company 1938), http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000019.htm?CCSI=254n

Perhaps the establishment of this immigrant neighborhood arose as increasingly large waves of more established American families moved to the suburbs, spurred on by the now widespread accessibility of low cost automobiles (thanks to Henry Ford’s model T assembly line innovation), as well as the Great Depression. According to Warner, “it was a time when the old Boston families left the city for the suburbs and when the new immigrants made a settled place for them- selves in the city” (Warner Jr.). In the residential area of the site between Harrison and Hudson Avenue, there seem to be clear signs of a flourishing neighborhood in 1938: there are plumbers, tailors, a home for children, lodging, the City of Boston Gymnasium and bath house, a bakery, an ice cream factory and a nursery. Quincy school and the Harvard Street Baptist church have not changed. Furthermore, it seems “flats” and “tenements” replaced some dwellings, perhaps to make room for an increasing influx of poor immigrants. Another interesting change in the site appeared in its westernmost block, bounded by Harrison Avenue and Washington Street. There, a Theater District seemed to have sprouted, with “Globe Theater” a “Moving Picture” place replacing a Business college and some stores. Perhaps the financial tumult of the times generated a surge in the entertainment industry, as depressed, unemployed citizens searched for something to bring up their spirits. However, though this neighborhood might appear to be flourishing to the modern observer, the dominant political and public institutions at the time probably thought otherwise. Prior to the 1930s, the American government avoided intervening in the housing industry on principal –it did not want to venture anywhere near socialism (Jackson). However, in light of the housing price collapse brought on by the Great Depression, President Roosevelt took a much stronger, interventionist policy, as evident in the policies he introduced with the New Deal (Jackson). In particular, the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC) dramatically changed the way neighborhoods were viewed and dealt with. In order to dole out mortgage aid packages to homeowners, HOLC created a comprehensive, unified system of appraisal, “initiat[ing] the practice of red-lining [neighborhoods]” (Jackson 197). The government agency ranked neighborhoods as being first, second, third or fourth grade, with first encompassing “quality” neighborhoods that were “new [and] homogenous” and fourth encompassing “undervalued neighborhoods that were dense, mixed or aging” (Jackson 197).

As Jackson aptly opines, “the HOLC simply applied these notions of ethnic and racial worth to real-estate appraising on an unprecedented scale” (199). Undoubtedly, this site must’ve been classified as a fourth grade site, as not only was it highly dense, it also bordered undesirable industrial areas, was populated by a mixed bag of immigrants, and consisted of relatively old structures that had remained unchanged since 1883. It might have even housed many sick or elderly residents, with some dwellings being labeled “Living in Hospital”. The low economic and societal stature of this site had important repercussions in the 1950s and onwards.

The 1950s: “Urban Renewal” leads to Urban Destruction

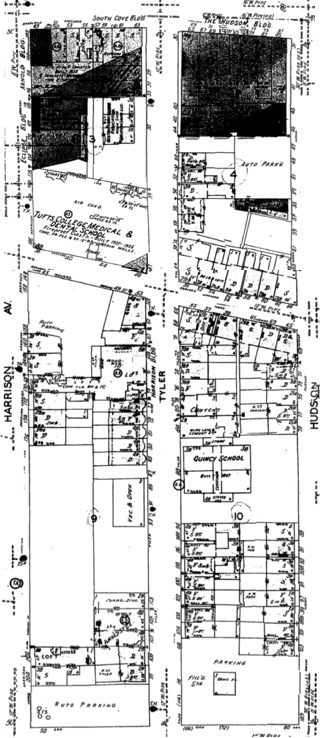

In 1933, the United States government passed a critical housing law that “authorized the Public Works Administration (PWA) to lend money to private corporations interested in slum clearance, made grants and loans available to public authorities for the same purpose [and empowered the] Housing Division to buy, condemn, sell or lease property for developing new projects itself” (Jackson 221). Perhaps this law explains the drastic change in the landscape of this site from 1938 to 1951. As seen in the 1951 Sanborn map in Figure 7, huge swathes of the neat, uniformly sized plots of dwellings were wiped out and replaced by empty lots labeled “Vac. & Open”, a total of eight parking lots, and Tufts College Medical and Dental institution.

Figure 7: Map showing total remodeling of former residential area of Chinatown, from Boston Massachusetts (Cambridge: Sanborn Map Company 1951), http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000019.htm?CCSI=254n

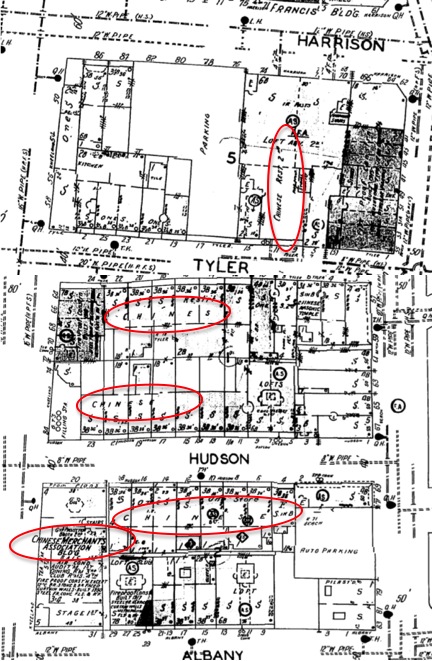

Perhaps the return of soldiers from World War II drove the expansion of universities, and as such under the permission of the US Government’s new housing legislations, Tufts was able to expand into this formerly residential neighborhood. The theater district seemed to continue to flourish, while many more dwellings were turned into “Flats” or “Lofts”, perhaps reflecting the onset of a new era of high-density living ushered in by the 1950 population boom. It is also clear the by this time, the few blocks in the heart of my site between Lincoln Street, Harrison avenue, Beach Street and Kneeland Street have truly established themselves as a “Chinatown” within Boston. Three rows of stores facing Tyler, Hudson and Albany street are all labeled “Chinese” or “Chinese Rest.” (short for restaurant), as shown in Figure 8 below.

Figure 8: Map showing prominent Chinese presence, from Boston Massachusetts (Cambridge: Sanborn Map Company 1951), http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000019.htm?CCSI=254n

By this time, the HOLC appraisals of the Great Depression must have thoroughly stigmatized this area of Boston, lowering property values to the point where only poor immigrants would want to settle here. The huge swathes of parking lots also point to a dramatic surge in car ownership that might have further drove suburban settlement. Regardless, it became clear that the area became home to a mainly Chinese community (the Syrian Church was gone), as other community centers such as a Chinese Masonic Temple and Chinese Merchants Association building sprung up, as shown in Figure 8. The fact that these areas were conspicuously labeled “Chinese” hints at discriminatory attitudes. The Leather District had transformed into an area of lofts and stores by this point.

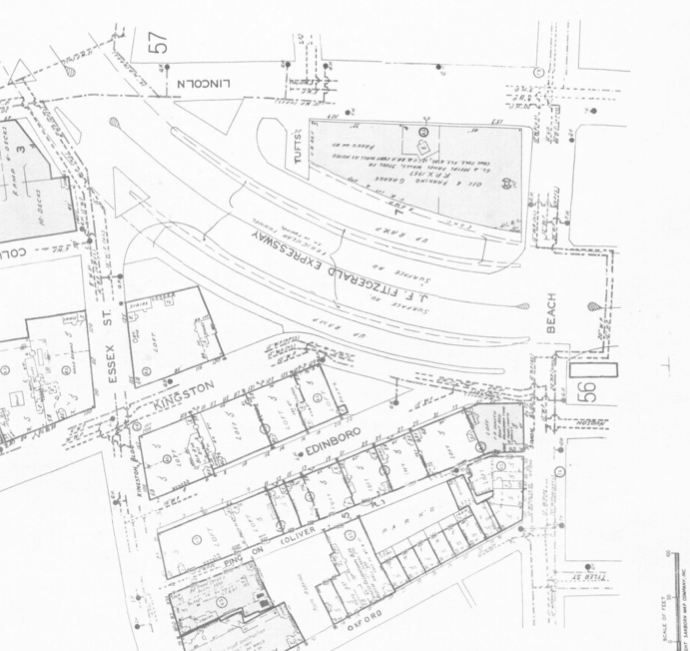

However, the most dramatic physical change to the layout of this site arguably appears in the 1972 Sanborn map: the Fitzgerald Expressway was build to cut straight numerous blocks, virtually eliminating an entire block of stores between Hudson and Albany Street. The road also cut straight through half of the Chinese Merchants Association Building. In fact, if one travels to the site of that building today, one is faced with the site in Figure 10.

Figure 9: Photo of former Chinese Merchants Association Building, taken in February 2013

Figure 10: The Fitzgerald Expressway cutting through a block in Chinatown, from Boston Massachusetts (Cambridge: Sanborn Map Company 1974), http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000019.htm?CCSI=254n

Figure 10: The Fitzgerald Expressway cutting through a block in Chinatown, from Boston Massachusetts (Cambridge: Sanborn Map Company 1974), http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000019.htm?CCSI=254n

The odd shape of the building shows a side that is too flat, sheared off to make room for the construction of the expressway. The legacy of discriminatory sentiments against poor, immigrant, high-density neighborhoods left by the government initiatives of the 30s resulted in the construction of a web of interstate highways often through marginalized neighborhoods. Continuing with the theme of urban destruction and renewal, Tufts University expanded, over taking some stores, dwellings and junk shops to create Tufts Medical College in 1954. The encroachment of Tufts upon this neighborhood’s territory is unsurprising, for as Professor Spirn once explained in class: “institutions make bad neighbors”. The destruction of the Merchants Association Building, as well as the elimination of the swathes of residences and stores for the Central Artery, is a physical manifestation of the marginalization the Chinese immigrants experienced during this time period. Since then, they have formed stronger community unions and have begun to assert their rights, standing up to city authorities to demand the preservation of the area we know as Chinatown today.

It is clear that this site has undergone numerous changes over time, being continually reshaped and remodeled by the political wills and popular trends of each passing era. However, a clear pattern can also be seen in this evolution: in each time period, the most influential driving force of change has been the economic climate of the day. From the expansion driven by mercantile prosperity, to the suburban flight of the Industrial Age, to the discriminatory sentiments fostered by economic woes in the Great Depression, it is clear that economic forces have had a dramatic impact on this site. This begs the question: how will today’s economic state influence the livelihood of Chinatown, South Station and the Leather District in the future? Will the gentrification and rising property values of the Leather District drive up rent prices in neighboring Chinatown as well? Will Chinatown’s commercial community be diminished, or will it continue to flourish? Only time will tell.

Bibliography:

Jackson, Kenneth. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press , 1985. Print.

Warner Jr., Sam Bass. "A Brief History of Boston." Trans. Array Mapping Boston. Cambridge: The MIT Press, Print.