A region’s economic development is frequently tied to many factors, some are related to the natural environment –the climate, the elevation, the availability of resources – while others are results of the people that occupied the region, such as transportation, ethnicity, length of settlement, technology, etc. In a historical city like Boston, one can easily trace the history of its various districts and pinpoint the influences of each of these factors. While researching the Financial District, I noticed that transportation had been one of the major driving forces throughout the history of the site. In this paper, I will examine the history and influences of streets and railroads in the Financial District area and discuss how these shifts in transportation played a key role in the economic development of this area.

Streets – the original Broad Street

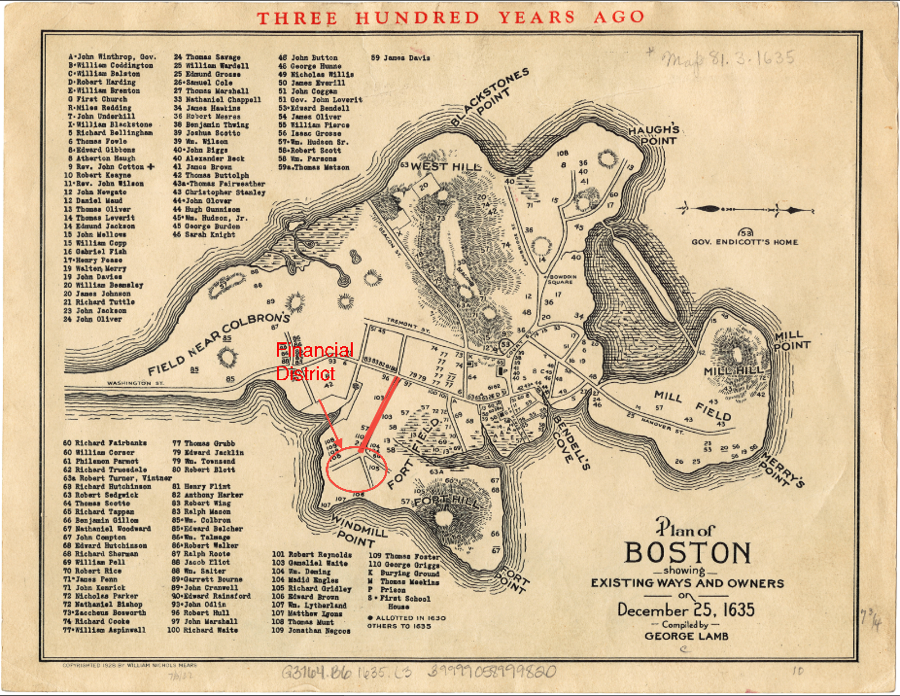

Figure 1. Map of Boston, 1635. Broad Street Highlighted. Source: Plan of Boston showing existing ways and owners on December 25, 1635 Author: Lamb, George Date: 1635 Location: Boston (Mass.). Norman B. Leventhal Map Collection at Boston Public Library.

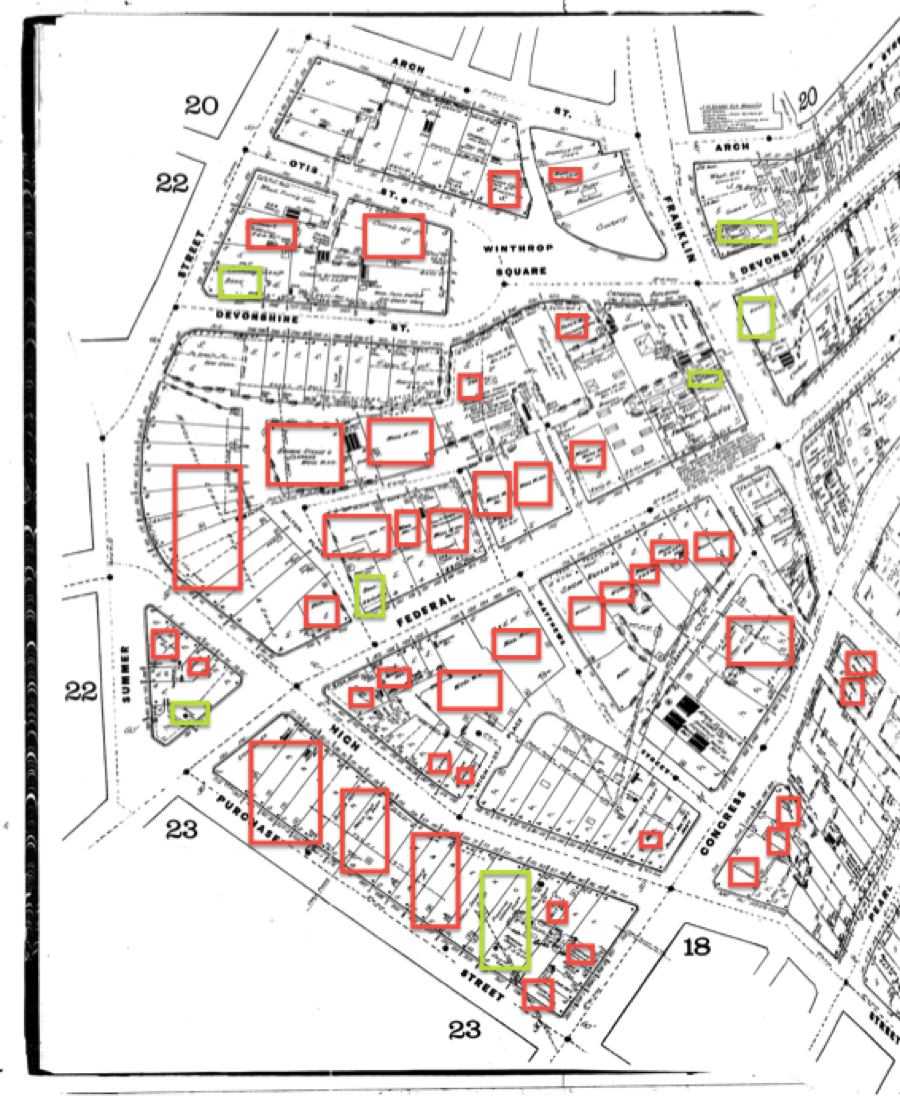

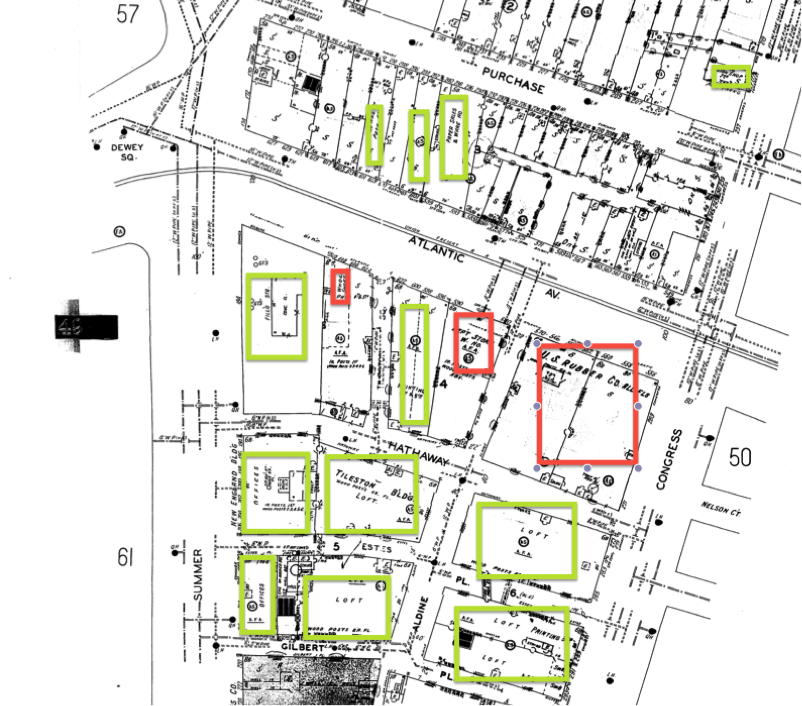

Figure 2. 1885 Sanborn Map. Red Squares indicate clothing-related facilities (stores, manufacturing plants, etc) and Green Square indicates banks. Source: UML Digital Sanborn Collection. http://sanborn.umi.com.libproxy.mit.edu/sanborn/image/download/pdf/ma/reel04/3693/00091/Boston+1885-1888vol.1%2C1885%2C+Sheet+19_a.pdf?CCSI=

The commercial development of the Boston Financial District had its origin in the construction of Broad Street in the 1600s. From one of the earliest maps of Boston dated in 1635 (Figure 1), it is clear that Broad Street was the only major street connecting the original site of the current day Financial District. Judging from the length of Broad Street and the name “Broad Street” itself, I estimate that it must have been one of the main hubs of commerce back then. Though I was unable to locate detailed maps of the area in the 1700s, I compared the 1635 map (Figure 1) and 1885 map (Figure 2) and conclude that, since the 1600s, this area has developed into the center of the textile industry in Boston, housing the majority of the wool warehouses and manufacturing facilities. What was interesting was the fact that many of the merchants at the time appeared to also reside at the same place where they conduct their businesses, as some of the structures on the map were marked residential (Figure 2). Clothing store and plant owners conducted their daily activities almost exclusively in this area and travel to the other parts of Boston via Broad Street.

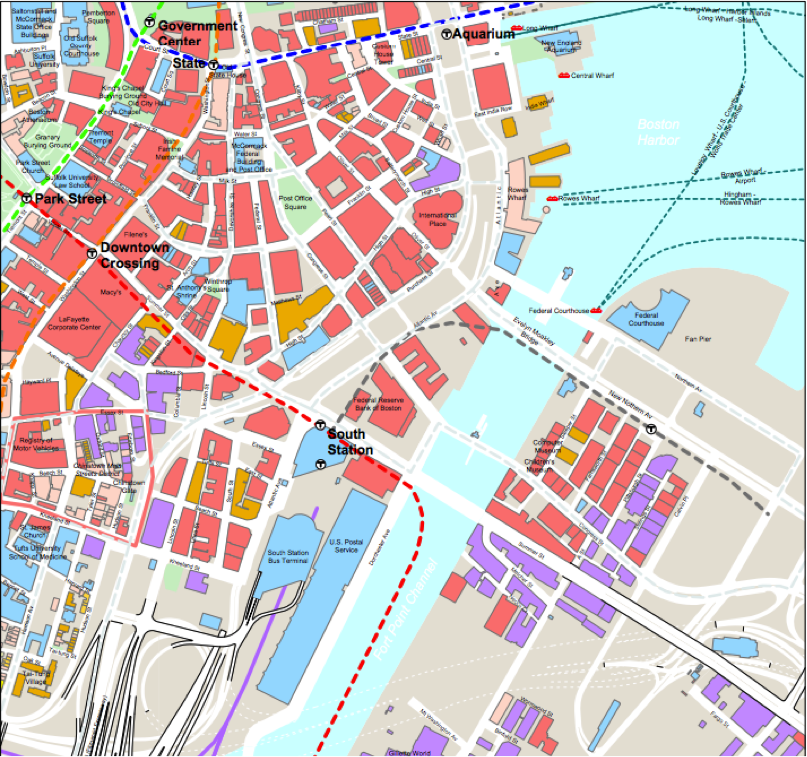

Figure 3. South Stataion/Financial District today. Red indicates Commerical Buildings. Red dotted line shows the MBTA Train line. Source: Boston Redevelopment Authority. http://www.bostonredevelopmentauthority.org/pdf/maps/southstation.pdf

One can observe from the 1885 Sanborn Map (Figure 2) that most of the industrial activities, namely, the wool plants and warehouses, congregated along Summer Street, which stood at the old site of Broad Street (as seen in Figure 1). The density of these industrial activities decreased as one moves farther away from Summer Street, indicating the crucial role of the street in bringing traffic and products to and from the wool shops. Even though Summer Street was no longer the only road connecting the Financial District area to the rest of Boston, its historical significance prevailed into the 1800s. Even in the current day, as I walked around my site, it was clear that Summer Street remained the busiest street in the Financial District, with the MBTA subway red line running directly underneath it (Figure 3), the Boston South Station sitting at a street corner, and many office supply stores, office lunch restaurants, banks, and office buildings locating along the street. It is easily the street with the most pedestrian and automobile traffic on my site. In fact, Summer Street is one of the four streets that continue across the Fort Point Channel, connecting to the now blooming Fort Point development district.

Streets – the impact of the Great Fire of 1872

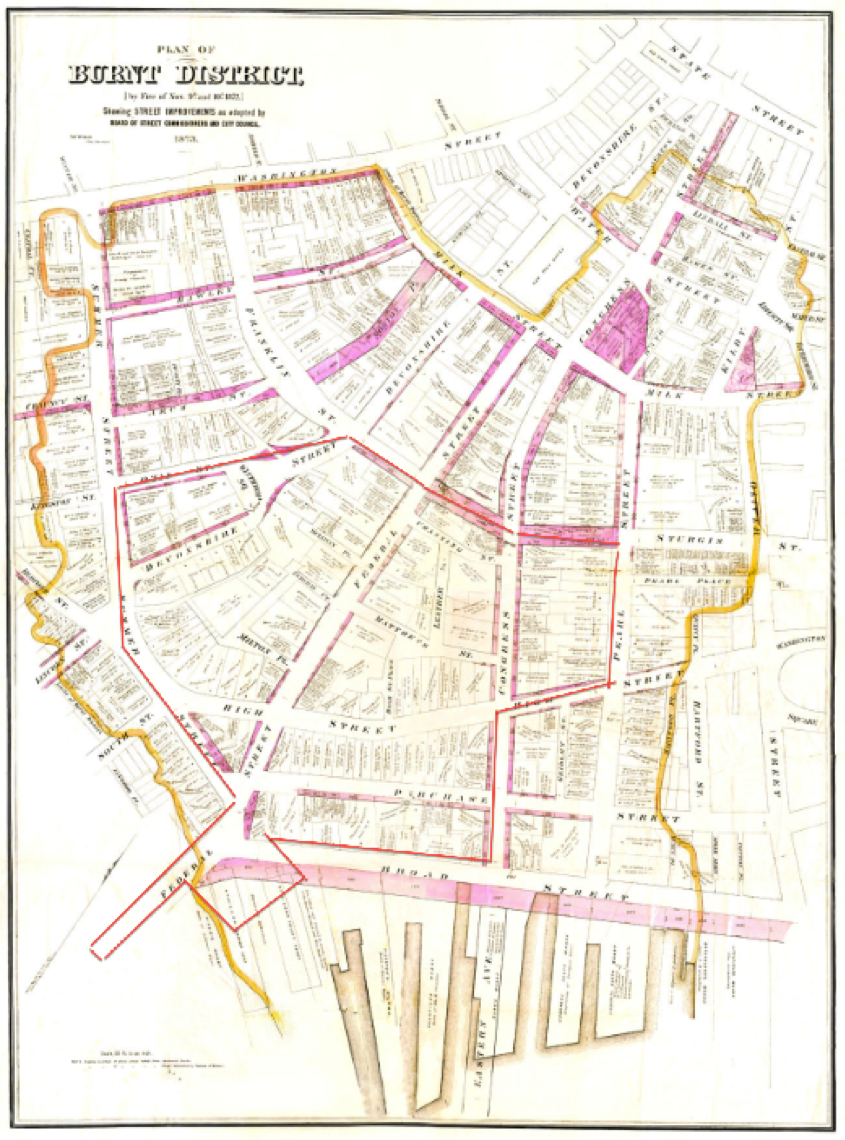

Figure 4 Burnt District of the Great Fire of 1872, produced by Boston city planners in 1873. Red area marked the boundaries of my site. Source: Damrell’s Fire. http://www.damrellsfire.com/maps.html

One cannot study the human history of the Financial District without looking into the Great Boston Fire of 1872. In fact, this fire consumed the entirety of the Financial District (Figure 4), and effectively wiped out all the original warehouses and residences on the site. The many underlying causes of the fire include lenient building regulations, prevalence of non-fire-safe buildings, warehouses storing flammable goods such as wool, textile, and paper, and poor fire department utilities[1]. After the fire, the majority of the existing buildings in the Financial District are made of brick and equipped with automatic fire alarm (Figure 2), as a consequence of the improved fire safety regulations. In reaction to the Great Fire, city planning took the chance to widen several major streets in the Financial District, including Congress Street, Federal Street, and Purchase Street (clearly visible when comparing maps of the era), alleviating traffic congestion on these streets. I expect the widened streets probably served to increase attractiveness of this neighborhood to businesses, since they could then support traffic demands unable to be met by older parts of Boston like downtown and Beacon Hill area. The characteristic wide streets in the Financial District further asserted it as the center of commerce and finance in Boston by making the area one of most car-friendly neighborhood in central Boston.

Railroads

Figure 5. Boston's Railroads in 1855. Source: David Ward, “The Industrial Revolution and the Emergence of Boston's Central Business District”. Economic Geography, Vol. 42, No. 2 (Apr., 1966), pp. 152-171. Published by: Clark University. Article URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/141915.

Wool warehouses, shoe stores, bookshops (printing and binding, specifically) and mill construction sites dominated the neighborhood in the 1800s (Figure 2). Walking around the block today, I could see that many of these warehouses were substantial granite structures, usually no more than 10 stories high, covering entire street blocks. In the 1800s, these wool and clothing manufacturing plants and facilities gathered in high density in this neighborhood and presumably attracted many railroad companies to route through the region. Several New England railroad companies established terminals near the Financial District[2] (see Figure 5), where the proximity to the existing industrial and commercial activities helped support the business of these railroad companies.

On the other hand, the new railroads probably also made the region more attractive to new businesses to move into the Financial District. The textile and clothing produced in Boston were easily transported to the other major industrial capitals, such as Providence, Worcester, and New York (Figure 5). In the mid 1800s, railroad stations in Boston were highly scattered, each owned by different railroad companies and connect to different regions in the country (Figure 5). When it became evident that having five railway companies servicing Boston separately was neither practical nor sustainable, these railroad companies combined their efforts to form the Boston Terminal Company and built a station that would serve as the central terminal for all the railroads – Boston’s South Station[3].

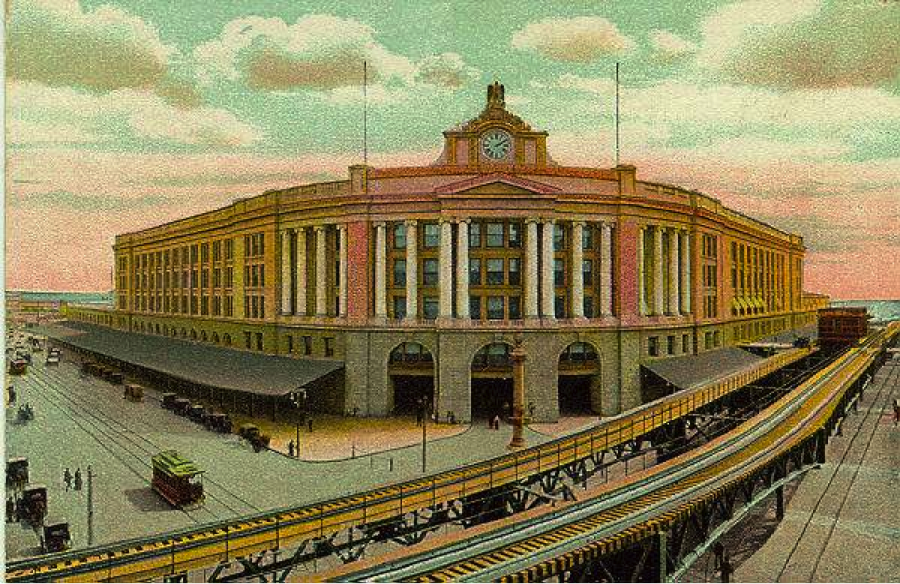

The site for the new South Station was chosen across the Atlantic Avenue from the Financial District, along the busy Summer Street. South Station had several geographic advantages. It was close to the waterfront, providing easy connection with the water transportation industry that brought goods around the globe. It was close to both the Financial District and the warehouse district, where workers and merchandize travel frequently [4]. These geographic advantages made the busiest transportation center in the world by 1916, handling over 38 million passengers[5] every year.

In addition to being able to transport goods cheaply and quickly, workers and business owners residing in the Financial District could also easily walk to these terminals and hop on a train to these major cities on the East Coast. In the late 1800s, this opened the area to the new and developing industries that are in need of office spaces and would benefit from frequent travelling, like the financial and industrial industries.

Figure 6. 1929 Sanborn Map. Red Squares indicate clothing-related facilities (stores, manufacturing plants, etc) and Green Square indicates finance-related facilities and offices. Source: UML Digital Sanborn Collection. http://sanborn.umi.com.libproxy.mit.edu/sanborn/image/download/pdf/ma/reel09/3693/00224/Boston+1929-Feb.1951vol.1%2C1929-Jan.1951%28South%29%2C+Sheet+49.pdf?CCSI=

The financial and insurance industries began to develop throughout the 1800s into the 1900s. Comparing Sanborn maps from 1885 (Figure 2) and 1929 (Figure 6), one can see the emergence and expansion of insurance companies, financial firms, general offices, and parking lots in the Financial District. The financial and insurance industry replaced the old residences and storefronts on State Street in the Financial District area.

Meanwhile, the manufacturing and handicraft industries seemed to be on the decline. As shown on the Figure 6, many of these original warehouses and workshops were converted into office spaces and residential houses. Given the state of manufacturing presence (more appropriately, the lack thereof) in downtown Boston currently, I suspect these manufacturing plants have been driven out of business by a combination of technological and transportation innovations. First of all, large, industrial scale machinery enabled more unskilled workers to enter these previously high barrier-to-entry industries. More importantly, the availability of cheap and fast transportation by car and air then further moved these plants to suburban areas across the country and potentially overseas.

Figure 7 South Station in 1899. Source: Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge: South Station, Boston, 1899. From an old postcard. URL: http://www.bc.edu/bc_org/avp/cas/fnart/fa267/trainstations.html

Figure 8. South Station today. Personal Photograph.

The automobile revolution began in the mid 20s. Simultaneously, South Station saw its decline in traffic and relevance. As automobiles became more affordable and entered more American homes, cars gradually replaced trains as the first choice mode of transportation. Urban roads and highways were constructed, further decreasing the need for trains. The train shed that once was along Atlantic Street in front of the Station had been removed. Comparing Figures 7 and 8, one can clearly see that the physical scope of South Station shrank greatly from 1899 to the current. Parallel to the rise and fall of the train as the predominant mode of transportation, South Station shifted from what I presume to be a reflection of technological progress at the time of its inception to the current-day representation of classical and traditional structures (Figure 7) amidst the contemporary fabric of the Financial District.

The railroad system supported the textile industry in the Boston Financial District, while the rise of air transportation and the highway system drove the industry out of the center of American metropolitans like Boston.[6] Though South Station still brings traffic into and out of Boston, the traffic now consists mostly of travellers and Financial District office workers instead of industrial goods. The South Station both reflects and bolsters the Financial District’s shift from housing industrial warehouses and plants to commercial office spaces.

Conclusion

Throughout history, the commercial activities in the Boston Financial District has been closely tied with the transportation developments in the region. The extension of Broad Street from Quincy Market brought specialized merchants and the textile industry to the Financial District, which in turn attracted the financial and insurance industries to relocate to that area. The main streets through the Financial District were widened after carefully planning in the city reconstruction process after the Great Fire of 1872, allowing the district to better adapt to the sudden gain in popularity of automobiles. Railroad companies saw the rapid growth of the region and construct terminals to take advantage of this commercial hotspot, making Dewey Square a key point into and out of Boston, further appealing to businesses. It is safe to say that the Boston Financial District area owed its prosperity to the progression in transportation technology and development. The close connection between economics and transportation exemplified here was a story told repeatedly in urban development all over the world, offering city planners a feasible option to develop economics by first focusing on transportation.

[1] “The Rebuilding of Boston. One Year After the Great Fire.” November 10, 1872. Boston Morning Journal XL (13): 509. 1873-11-10.

[2] David Ward, “The Industrial Revolution and the Emergence of Boston's Central Business District”. Economic Geography, Vol. 42, No. 2 (Apr., 1966), pp. 152-171. Published by: Clark University. Article URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/141915

[3] “History of the Station”, South Station, Boson’s Great Room. URL: http://www.south-station.net/Station-History.htm

[4] Sam Bass Warner, in Mapping Boston, edited by Alex Krieger.

[5] “History of the Station – Through the Years,” South Station Boston’s Great Room. URL: http://www.south-station.net/Station-History/Throughtheyears

[6] Kenneth Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (Oxford, 1985).