In most urban environments, one often finds it difficult to isolate the development of the natural processes from the human intervention that began hundreds, or even thousands, of years ago. Our ancestors not only adapted to the natural environment they inherited, but also altered it to create a friendlier place for our day-to-day lives. The Boston Financial District is a prime example of how we have drastically shaped the natural environment to suit our commercial and transportation needs. To illustrate the evolution of natural processes and the human factors that influence the ecosystem, this paper traces the history of the site and analyzes maps and major events that occurred in different eras to demonstrate how they impacted the natural processes on the site and vice versa. A discussion of the microenvironment and climate in the current day follows to further illustrate our role in its current natural environment. Throughout the history of Boston, human progress and natural processes intertwined and constantly exerted impact on one another to form the city as we know it today.

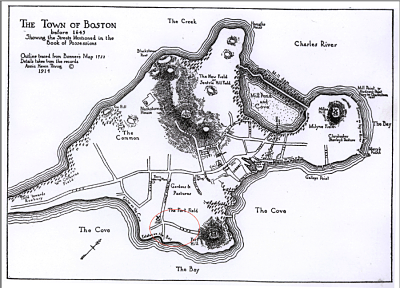

Figure 1: Map of Boston in 1643. Source: Massachusetts Historical Society.

Shown above is a map of the town of Boston before 1643, drawn in 1914 based on historical maps. The red circle on the lower part of the map is approximate location of the Financial District and Dewey Square area. One can see that the site is situated along the original shoreline and thus has been the southern most corner of the pre-landfill Boston. Also worth noting is the topography of this particular site. The area is relatively flat, as indicated by the name “The Fort Field.” The uniformity in elevation of this area and the proximity to the shoreline could have made the site an appealing one to early Puritan settlers, since transportation infrastructures require less human and capital resources to construct on flat land than on hilly areas.

Moreover, there is a small mountain immediately to the east of the red circle on the map. This mountain no longer exists in the current day, possibly because of the ensuing landfill projects. When urban planners were looking to expand the Boston land area, this mountain with its abundant soil might have contributed to their decision to fill in the wetland that is to the south of the Financial District area. This speculation provides an intriguing case of how the natural environment in one area (in this case, the mountain to the east of the site) could impact human decisions and result in the transformation of the natural environment elsewhere (the landfill to the south).

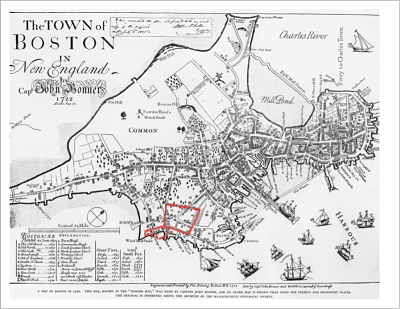

Figure 2 Map of Boston in1722. . Source: Massachusetts Historical Society

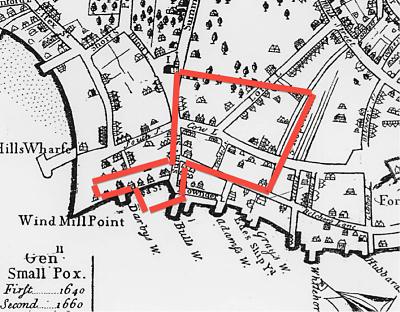

Figure 3 Map of Boston in 1722, Close up view . Source: Massachusetts Historical Society

From 1643 to 1722, Boston transformed from a recently settled Puritan colony to the political, commercial, financial, and religious center of New England [1]. One can observe that settlers have begun their efforts to transform the landscape in this time period. What appear to be residential houses were constructed and the density of streets increased drastically. At this point, the area was known as Old South End and was a residential site of elegant mansions and tree-lined squares that emulated the aristocratic boroughs of London [2]. A network of piers was built all along the shoreline for the easy shipments of goods from and to its surrounds regions as well as Europe. Judging from the density of buildings and streets, one would estimate that downtown is located near the Boston Common to the north of the site. Though the Old South End is not considered downtown, its naturally even landscape and proximity to sea made this area a prime site for high-end real estate.

Figure 4 Boston Financial District. Notice the lack of street plans.

Figure 5 Boston Financial District at night. Source: Hector Velazquez.

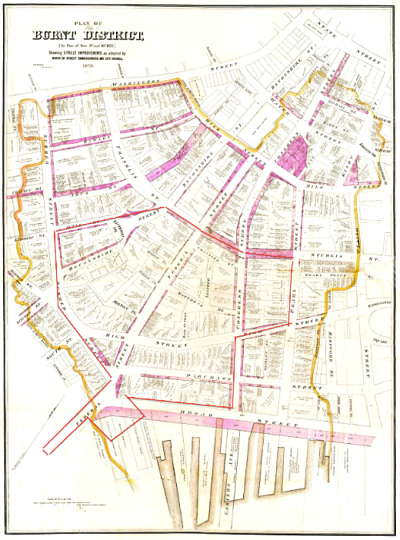

Fast fowarding to the current day, the Financial Distrct is known as a hub of skyscrapers and one of the most concrete representations of Amreican Capitalism. Walking around the district, one can observe few natural objects (see Figure 4). A note worthy event, the Great Boston Fire of 1872 obliterated most of the Boston Financial District. As seen in Figure 6 below (the site is outlined in red), almost the entirety of the site resides within the burnt zone in the Great Boston Fire. Because of that, it is nearly impossible to find traces of the original natural environment and older historical structures. The Financial District, as we know it today, is formed during the reconstruction of the area after the fire, around the same time as the creation of the financial and insurance industries in the 1800s.

Figure 6 Burnt District of the Great Fire of 1872. Source: Massachusetts Historical Society.

Figure 7 Trees in Financial District

Figure 8 Tree growing under the Bank of America building.

Figure 9 The bush blown over by the wind.

It is difficult to define what is indeed “natural” in a metropolis such as Boston. Since it first became in settlement in the 1600s, its residents have continuously shaped the natural landscape for their daily comfort and needs. The Financial District especially exemplifies this effort to construct a modern city at the expense of the natural environment. Looking around, most streets on the site embrace the absence of even street plants, let alone any animals. If one is determined to find natural objects, one can perhaps spot the occasional street trees on the smaller streets in the shadows of bank-owned skyscrapers. It is clear that city planners plant the trees intentionally, perhaps in order to add some green to this “concrete jungle.” However, most of these trees are young, lean, and unhealthy looking. They stand in little patches of soil surrounded by the pavement, and presumably could get very little nutrient from them[3]. Upon entering the Financial District, one can right away feel the local temperature drop by several degrees. The skyscrapers not only block the majority of the sunlight, but also create tunnel effect (due to their height and density) and increase the wind speed significantly. A lot of the artificially planted trees (Figure 8) and bushes (Figure 9) look both frail and blown over by the wind due to the lack of sun and strong wind.

Figure 10 Trees on the rooftop.

A somewhat unique phenomenon to this district might be the trees planted on rooftops (see Figure 10). In order to maximize the utility of land use on the ground, the streets and pedestrian sidewalks are designed to be as wide as possible within the constraint of the buildings on both sides. I suspect street trees are deemed a waste of precious land space. Building managers, in an effort to beautify the work environment and simulate nature, have creatively utilized the rooftop spaces and turned them into mini elevated gardens. It is apparent that city planners and building managers have put in tremendous effort to foster the natural environment given the limitations imposed by the skyscrapers and the commercial needs they server. Nonetheless, despite all of their efforts, the street plants are growing poorly, and the Financial District will most likely retain its cold and concrete outlook in the foreseeable future.

Figure 11 Before the Big Dig & Greenway (6 lane Central Artery)

Figure 12 The Greenway.

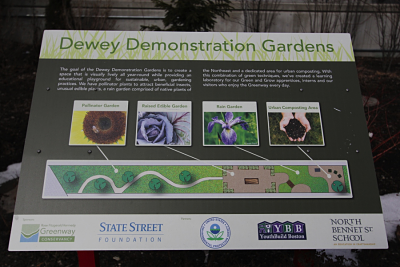

Figure 13 Plate describing the Greenway Garden

What used to be ocean on the southern most end of the Financial District are now the Greenway Project and the Boston South Station. Two major events have taken place in this area. The first is the construction of this particular landfill project, South Cove, lasted from 1806 to 1843 [4]. The second major cause of changes in the local natural environment is the Central Artery/Tunnel Project (CA/T), unofficially known as the Big Dig[5]. The Central Artery (Interstate 93), which opened for traffic in 1953[6], used to span six lanes and cut right between the edge of the Financial District and the South Station, directly on top of what is current Atlantic Avenue. The Big Dig project moved the Interstate underground, and created the Greenway in place of the old Interstate. The Greenway presents an open area in the middle of the city for primarily recreational use. On weekdays, food trucks are parked in the plaza in Dewey Square, serving the white-collar community in the Financial District. At the end of the plaza, there are small plots of land known as the Dewey Demonstration Gardens. These gardens feature a diverse set of plants, curated to look lively in all seasons and provide a refreshing setting. Even though it is the middle of winter, one can still see signs of livelihood in these gardens, in sharp contrast to the trees in the Financial District.

The Financial District and Greenway are located no more than 300 feet apart and the street trees in these two areas are both planted intentionally with the objective of improving the local environment. However, the trees on the Greenway are endowed with much more sunlight and soil space for them to grow, whereas those in the Financial District seem to struggle to adapt to the harsh urban environment. This drastic difference in the wellbeing of street plants is attributed solely to the difference in the man-made environment, and is therefore a classic showcase of how much human activities can impact the surrounding natural environment.

One cannot discuss the natural processes in the urban area without considering the human factors that played a significant role in its evolution, nor can one speculate about the urban development at any particular site before taking into account its environment. The Financial District and its predecessor the Old South End were established on its current location largely because of its geographical features; and the establishment of this urban center in turn transformed the original environment. The interaction between humans and natural processes is and will be a recurring theme in any discussions about urban development; and it is exactly this intertwining relationship that enriches the history of an urban site like the Financial District.

[1] Personal knowledge. I have lived in the suburbs of Boston for the past 5 years.

[2] Sammarco, Anthony Mitchell. Boston's Financial District. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Pub., 2002. Print.

[3] Spirn, Anne Whiston. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design. New York: Basic, 1984. Print.

[4] Boston: History of the Landfills. http://www.bc.edu/bc_org/avp/cas/fnart/fa267/sequence.html

[5] Personal knowledge, as a result of living in the Boston area for the past 5 years.

[6] Boston.com Big Dig Timeline. http://www.boston.com/beyond_bigdig/timeline/