Downtown Crossing

Introduction

Over the past two and a half centuries, the four-block region nestled in the heart of Downtown Boston has undergone significant changes. Even though most of the property’s land use has remained commercial throughout the last two hundred years, the constant rotation of storefronts and owners reveals an entrancing and detailed story about the cultural and social shifts of the urban area. From the industrial revolution to the ‘white flight’ phenomenon, the discoveries in the technological world and trends in the population have had a tremendous impact on the dynamic of the downtown region.

As mentioned before, Tremont Street, School Street, Washington Street, and Winter Street surround the four-block area of focus. Despite the massive changes to Boston’s topography during the 19th century land fill project as mentioned in Anne Whiston Spirn’s Granite Garden, this block of space has firmly held in its central location. The peninsula that took on the name of Boston nearly doubled in size as the surrounding waterfronts were replaced with land taken from nearby hilltops, resulting in a noticeably flatter landscape with more space to construct new residences and commercial buildings.

Under English Rule

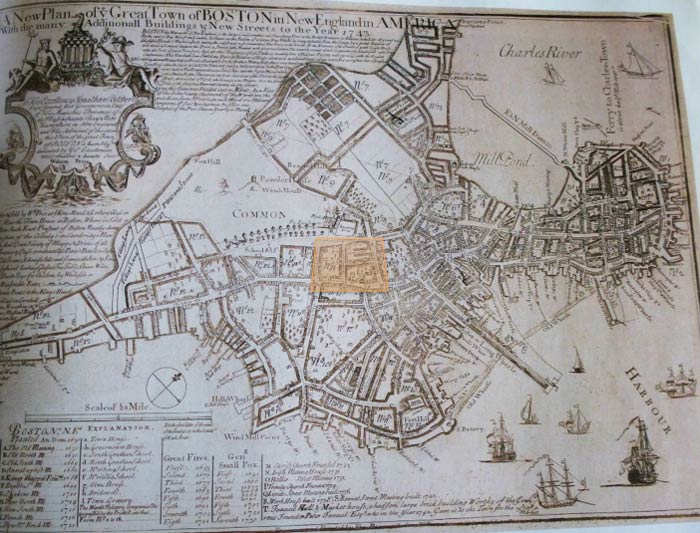

The central position of this region, particularly during Boston’s peninsula days, made it an area of high traffic and constant bustle. Back in the mid-17th century and well into the 18th century, cities tended to be primarily ‘walking cities’ due to the lack of technological advancements: to give some context, the introduction of the automobile was not until the late 19th century. This pedestrian-heavy age resulted in high concentrations of buildings and houses in small areas, since travel was time-consuming and tiring. During the mid 1700’s, the core of the city was home to the local political hub. Figure 1, which shows a map of the city in 1743, demonstrates this point exactly: located on the corner of School Street and Marlbrough Street (presently known as Washington Street) was the Old Meeting House, and one block west stood the French Meeting House. The King’s Chapel resided one block north, at the corner of School Street and Treamount Street (now spelled Tremont Street), where it still stands today. And most notably, on the south side of Governour’s Lane (now Province Street) stood the governour’s house.

Figure 1: a map of Boston in 1743. Taken from Mapping Boston

Figure 1: a map of Boston in 1743. Taken from Mapping Boston

The placement of these buildings was definitely not accidental: people congregated in the center of the city because it was the most convenient location, and events of both the political and social nature were held in this downtown area. Especially with the political tension brewing between England and the Colonies a mere thirty years before the Declaration of Independence, having a government-focused center was crucial to address the priorities of the city. On an interesting note this map clearly indicates the British stronghold over the Massachusetts colony, with the very proper English spelling of Treamount Street and Governour’s Lane. The name of King’s Chapel again reiterates the overlying dominance that England had over the American peoples during this time. Britain’s repeated and obnoxious reminders of their power over the people, such as the King’s Chapel, gives us a glimpse into the kind of relationship that the colonies had with the ‘mother’ country during the mid- 1700s—a subordinate, powerless one.

Transportation Revolution

The middle of the 19th century was characterized by the industrial revolution and the growing suburban housing market that followed. In the 1820s, the locomotive was introduced to the public, and it had huge urban repercussions. As Kenneth T. Jackson puts it in his book Crabgrass Frontier, the ease of access that people now had to public transportation crushed the concept of a ‘walking city.’ (20) And it was not just trains, it was all kinds of new transportation: Abraham Brower brought the omnibus to Boston in 1835. (34) The steam ferry became a popular and cheap form of transportation, and seeing that Boston was a peninsula until the 1830s, this method of transportation was very relevant. Although the introduction of the omnibus and the steam ferry were far from seamless, the concept of public transportation was enough to encourage people to move away from the city and into the surrounding neighborhoods. (35) The appeal of more space and larger houses attracted the upper middle class, who fled from the cities at a significant rate. People came into the city on a daily basis for work purposes, and then retreated every night to their nice home and family in the suburbs. An 1823 advertisement lays out the new situation perfectly: “a place of residence [with] all the advantages of the country [and] most of the conveniences of the city” (32).

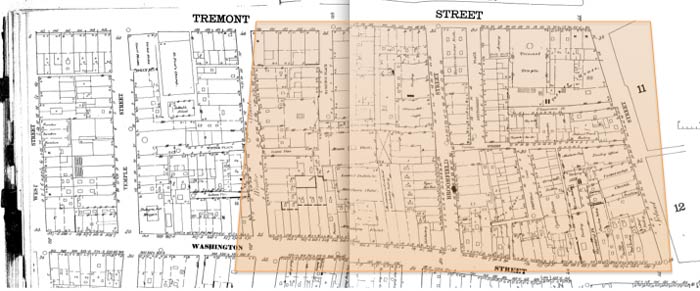

Figure 2: a map of Boston in 1867. Taken from Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps. (CLICK TO ENLARGE)

Figure 2: a map of Boston in 1867. Taken from Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps. (CLICK TO ENLARGE)

The 1867 map shown in Figure 2 demonstrates the dramatic changes brought on by the transportation revolution. What once used to be an area where the governor could live had turned into a completely commercial area. There was no longer a central meeting place for general purposes. Instead, a music hall charged admission for weekly performances. An opera house took the place of the governour’s house. The Tremont Temple and Universalist Church joined the ranks of the King’s Chapel. Hat factories and paper box companies claimed small plots of land while machine shops and sawing workshops made neighbors with the carpenters. During the mid-1800s, the downtown area had become just another stop for the omnibus full of people heading to work.

A Working Hub

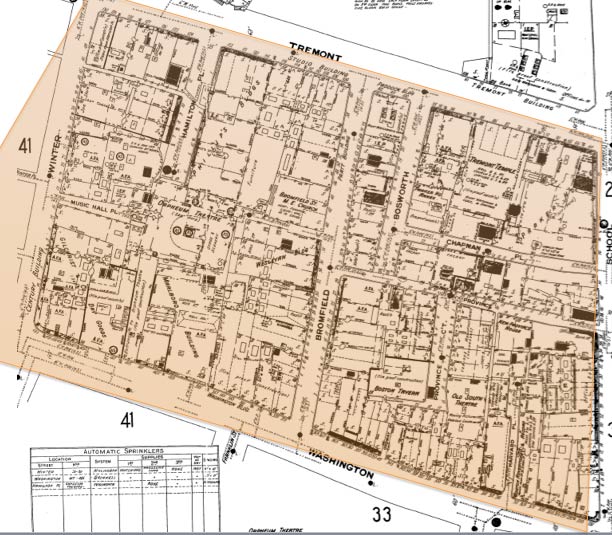

As the turn of the century neared, there was a slight but significant shift in the downtown storefronts. In Figure 3, which shows a map of the area in 1895, the number of factories has decreased, and almost disappeared from the scene altogether. In their place, small office buildings have sprouted up. Clustering together around the corners of the neighborhood, the replacement of the factories with new office spaces is an upgrade to the status of the downtown area. A potential reason for this change in property use during the mid 1890s may have been the establishment of the assembly line. As Professor Spirn mentioned in class, the automobile first became popular around the early 1890s and the Model T was introduced around 1910. The Model T was the first major application of the assembly line, a technique that would eventually come to dominate the manufacturing world. Since factories were interested in producing as much of their product as possible to maximize their profits, they needed as much space as they could afford to house production lines and mass assembly systems. Probably finding a home in the more expansive suburbs, the more industrial component moved away from the center of the city.

Figure 3: a map of Boston in 1895. Taken from Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps. (CLICK TO ENLARGE)

Figure 3: a map of Boston in 1895. Taken from Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps. (CLICK TO ENLARGE)

With the explosion of office buildings in the area, a sharp rise in the number of print shops was sure to follow. One of the most noticeable features on the 1895 map in Figure 3 was the abundance of printing shops in such a small region. Counting at least ten of these little shops, all on the southern half of the four-block region, they seemed to be paired up in groups of two, practically neighbors with each other. Again, during the mid 1890s, cars were a new technology—a mode of transportation for the rich. It was not a common commodity for the average citizen, as it was still a new concept. And much unlike the working environment today, public transportation dominated the commuting world and offices bought their supplies from local companies. There were no office supply department stores like Staples, where secretaries could order pens and paper in bulk. Printers were not readily available for personal use—it was probably still a relatively complex process to print several copies of one form. This combination—the one of no private transportation for quick errands and the lack of in-house printing capabilities—resulted in a need for local printing shops near office buildings. Secretaries would run around throughout the day, stopping by the local printing shop a few doors down to pick up some papers, and maybe the photo shop if they needed something printed in higher quality. The way in which the construction of printing shops closely follows the construction of office buildings is fascinating—the epitome of cause and effect.

The Mass Production Effect

During the turn of the century, assembly lines and mass production took front and center stage in the manufacturing world. With the increase in products, small shops were slowly starting to disappear, replaced by larger storefronts. In the map of 1909—Figure 4—the biggest change occurs on the corner of Washington Street and Winter Street, where at least five separate properties were engulfed to create Gilchrist and Co. Dry Goods. The number of print shops drops from ten to a mere one, suggesting a technological advancement that made personal printing much simpler and cheaper.

Figure 4: a map of Boston in 1909. Taken from Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps. (CLICK TO ENLARGE)

Figure 4: a map of Boston in 1909. Taken from Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps. (CLICK TO ENLARGE)

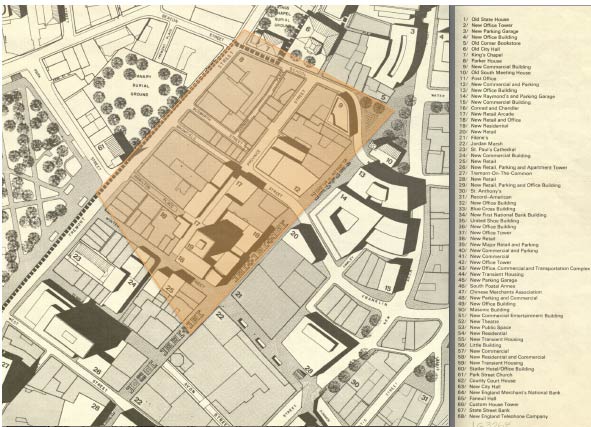

Up until the mid-20th century, the buildings and property sizes remained relatively the same. Besides Gilchrist and Co.’s efforts to combine several properties for the sake of the dried goods industry, the most common changes have been in ownership and storefront. But with World War II came a complete makeover of the downtown area. In 1968, Victor Gruen Associates had planned to change Downtown Boston once and for all. In Grady Clay’s Close Up: How to Read the American City, Gruen is described as the “20th century rational solution to large-scale urban problems” (61). Gruen was widely known for his architectural and planning techniques that revolved around the automobile and human consumption. Shopping malls and parking garages made frequent appearances in his plans, and his plans for Boston’s Central Business District Urban Renewal project was no different. (59) As seen in Figure 5, the entire block between Bromfield Street and Winter Street was being taken over by large retail buildings, with office space on the upper floors. On the south corner of Washington and Bromfield, a towering parking garage would take over almost a whole block. Filene’s, a clothing department store, would complete the retail section of the outdoor shopping mall, while planters in the middle of Washington Street would deem it purely pedestrian. This urban renewal era left behind the concept of small, individually owned shops and quickly put in its place a commercial retail haven. The trend towards larger, more uniform building structure mimicked the residential trends of the time: around World War II, mass produced houses were springing up everywhere in what were called Levittowns. These planned communities in the suburbs were comprised of rows and rows of identical houses. One house design could become an affordable living option for hundreds of different families in the middle class. Just like these Levittowns were creating residential neighborhoods of a large scale, Gruen and his company were building a shopping neighborhood of a large scale.

Figure 5: a map of Boston in 1951. Taken from Boston Redevelopment Authority.

Figure 5: a map of Boston in 1951. Taken from Boston Redevelopment Authority.

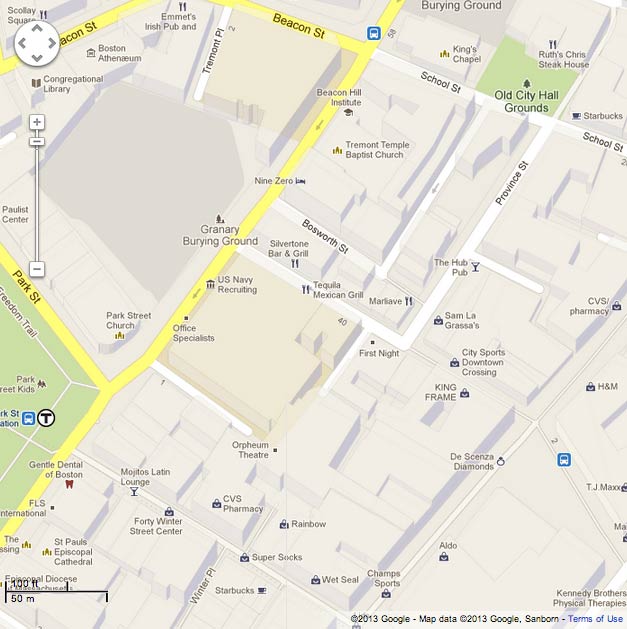

Compared to the map of Downtown Crossing today, Gruen’s vision towards a more organized retail mall was insightful, as the general concept remains to this day. In Figure 6, the current map of the city, a Macy’s department store stands on the corner of Washington Street and Winter Street, and chain stores line both sides of Washington Street. It is crazy how accurate Gruen’s vision of the urban trends were: the high-rise residential tower that Gruen had proposed in his plans came to fruition just five years ago, with the opening of the 45 Province apartment complex on Province Street. And although there are no planters in the middle of Washington Street like Gruen’s map had shown, that street still remains mostly pedestrian, as it is topped with cobblestone instead of the typical concrete.

Figure 6: a map of present-day Boston. Taken from Google Maps.

Figure 6: a map of present-day Boston. Taken from Google Maps.

Conclusion

Downtown Boston has had its highs and lows over the past two and a half centuries. Starting as the political center, the region was privy to housing some of the highest officials, while simultaneously being the communal meeting place for the city. Then, with the transportation revolution, a rough situation ensued as people moved away from the city and small factories took up shop. The noise and air pollution did not help. As offices took over central Boston, the area got a little nicer, and with the turn of the century, the area had become a place where people came for music and opera. And by the 1960s, Gruen had converted the area into a shopping haven. Even when huge malls were popping up in the suburbs, closer to people’s homes, this was meant for the driving family and was made more attractive than those on the outskirts. With this new implementation of shopping malls, the downtown area no longer became deserted on weekends: families could now come to the city to relax, instead of solely work.

The history of Downtown Boston during the past two hundred fifty years tells an accurate story of trends that cities around the nation faced. Faced with public transportation and the suburban exodus, central Boston experienced some drastic changes. But to this day, it remains a central hub of the city and epitomizes the social and cultural trends that sweep the nation.

Sources:

Boston, Massachusetts [map]. 1895. Scale not given. “Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1867-1970--Boston”. Sanborn Maps.

Clay, Grady. Close Up: How to Read the American City. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1973.

Jackson, Kenneth. Crabgrass Frontier. New York: Oxford University Press. 1985.

Krieger, Alex and David Cobb. Mapping Boston. Cambridge: MIT Press. 1999.

Spirn, Anne Whiston. The Granite Garden, Urban Nature and Human Design. New York: Basic Books, Inc. 1984.

Non-cited images and edits to maps by author.