Downtown Crossing

Introduction

Urban influences have visibly taken over most of the region bordered by Tremont Street, School Street, Washington Street, and Winter Street. The streets are lined with buildings in pretty much every direction. With the heavy traffic on the Tremont side and constant pedestrian flow on the Washington side, a combination of concrete, cobblestone, and pavement cover almost the entirety of the ground. The sidewalks lay bare with the exception of the occasional—yet strategically placed—lamppost to emphasize the historic significance of the neighborhood. In such a bustling area, it is easy to forget that nature and its processes play such a vital role in the development of the Downtown Crossing area. But the little reminders that pop up in several areas demonstrate the power that nature continues to hold in even the most urban neighborhoods, despite the city’s constant attempts to manipulate appearance.

History

For a little bit of history, Boston started as a peninsula with such a skinny neck that it practically looked like an island. Winds focused on the abundant coastline and the numerous hills. When the population numbers started to skyrocket, there just was not enough land on the peninsula to fit everyone. The landfill project took over the second half of the 1800s, and was done before the turn of the century. In the short amount of time that the project took, the size of Boston nearly doubled and the land was significantly flatter, allowing for more residential and commercial buildings to pop up.

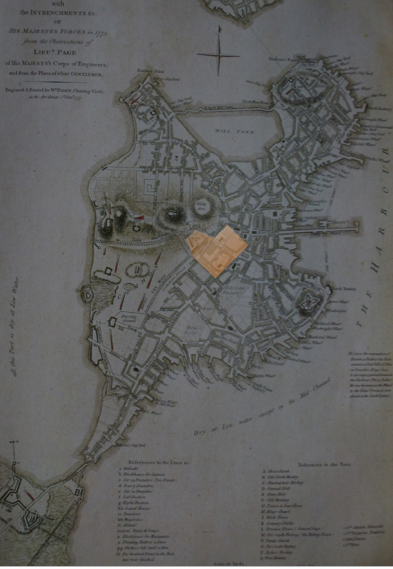

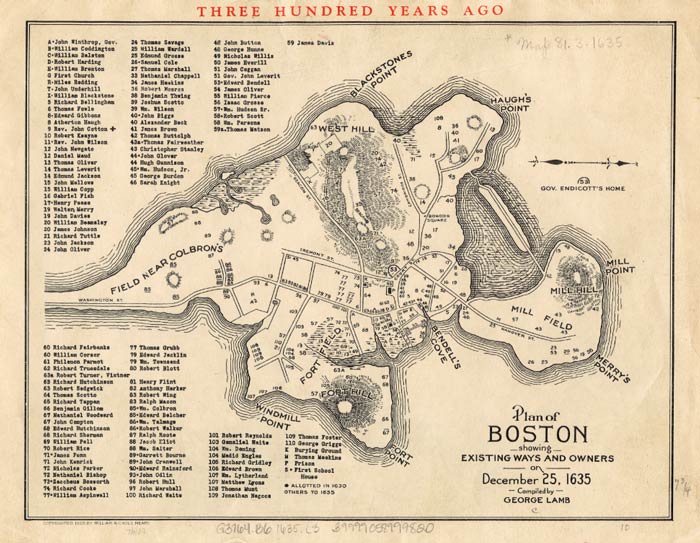

Before landfill was added to the greater Boston area, the Downtown Crossing site was located in the dead center of the peninsula: at the base of the Beacon Hill and Valley Acre merging, as seen in Figure 1. The final declines of these two slopes landed right in the backyard of the burial grounds which assumed its position at least 150 years prior, shown in the 1635 map of Boston (Figure 2). This strategic location was both an advantage in the urban and natural sense: the central spot made it a point of high traffic and constant noise, while simultaneously being at the base of a hill allows for a steady water source. But eventually, the urban development of the area took front stage as this area transformed into the neighborhood it is today.

Figure 1: a map of Boston from 1775, with the Downtown Crossing site highlighted in orange.

Figure 1: a map of Boston from 1775, with the Downtown Crossing site highlighted in orange.

Figure 2: a map of early Boston, 1635.

Figure 2: a map of early Boston, 1635.

Plants

The Granary Burying Ground, the Irish Famine Memorial on the School-Washington Street intersection, the green garden in front of Old City Hall, and the sidewalk surrounding the Province 45 apartment complex have one thing in common: they house the only remnants of tree growth in the immediate area. At least half of them are imported and artificially planted: a clear indication that the city and its residents intend to keep this area well pruned and uniform at all times.

Figure 3: these plants growing at the base of a tree trunk

Figure 3: these plants growing at the base of a tree trunk

are not the work of the city. This is an example of

the natural growth in the area.

The Granary Burying Ground, which has been around for at least three hundred years, exhibits a variety of healthy plant life. Grass surrounds the tombstones of John Hancock and Samuel Adams, trees climb to heights reaching the sixth floors of the adjacent buildings, and an abundance of plants sprout at the bases of some tree trunks. Due to the long history of this burial ground, plants have sprouted and flourished here without the help of the city. As seen in Figure 3, the bushy plant growth surrounding the trunk base does not seem to be the work of society. It arose from the open land in the burial site, a rarity in this urban environment, which provides more nutrients in its soil, more access to water, and more space for roots to expand underground. This historic site has been around longer than the City Hall building two streets down, as are some of the trees within the grounds. But despite the age of the trees, the city still has taken it upon themselves to rearrange the placement pattern to increase the aesthetics of the area. As Spirn states in The Granite Garden, Urban Nature and Human Design, “trees of a single species are planted equidistant in row to achieve a uniform visual effect.” (Spirn 179) This phenomenon is obviously implemented in the façade of the Burying Grounds. Figure 4 demonstrates this perfectly: the photo on the right portrays the straight line of trees running along the entrance. In comparison to the rear of the burial grounds, which takes on a more haphazard organization of tree placement, the front appeals more to the public due to the evenly spaced position of the trees. This futile attempt to add some uniformity to an area of such historical importance is countered by the natural processes in the area. Even though the city has tried very hard to create a uniform wall of trees to guard the graveyard, the trees refuse to stand up straight. The tree in Figure 5 is just one of many examples of the crooked trunks, its growth influenced much more by natural resources like light than by the poorly chosen placement by the city.

Figure 4: the trees toward the back of the burial ground (on the left) are not planted

Figure 4: the trees toward the back of the burial ground (on the left) are not planted

in an apparent pattern while the trees at the front of the burial ground (on the right)

are lined up parallel to the street..

Two blocks to the east, plant life is faced with drastically different conditions. The Irish Famine Memorial is trapped on the corner of a busy intersection: School Street and Washington Street. Whether it is a path heavily worn by foot or by car treads, the area seems to be constantly full of traffic. Groups of three or four trees are planted in succession, again evenly spaced along the sidewalk. In The Granite Garden, Urban Nature and Human Design, Spirn lists off the countless factors that contribute to the eventual demise of the street tree. Fed by infertile soil, chained by bicycle locks, trapped by wood stakes, clipped by passing automobiles and buses, and destined to a life in the shadows, these street trees endure an incredibly hostile environment that is nearly impossible to survive (Spirn 175). Due to this harsh environment, the average lifetime of a tree is approximately ten years! (Spirn 171) Looking at the line of trees parallel to Washington Street, as seen in Figure 6, it is easy to see the unnatural component. Covered by metal grates, these trees’ roots struggle to receive the nutrients necessary to thrive. This severe limitation stunts their growth in both the vertical and horizontal directions. But nature continues to push through the manmade boundaries: on the near tree in Figure 6, the left part of the trunk seems to be fighting its way out of the cage. The roots underneath are also starting to upset the evenness of the grate surface, pushing it upwards along the edges. The amount of strength that this tree possesses—one where not even a metal grate can discourage it—demonstrates the power of natural processes.

Figure 5: one of the trees in the front line,

Figure 5: one of the trees in the front line,

growing in a slanted manner.

Figure 6: the street trees in the Irish Famine Memorial

Figure 6: the street trees in the Irish Famine Memorial

plaza are not uniform, despite the city’s efforts.

Even though the walk from Granary Burying Ground to the Irish Famine Memorial is only five minutes, the conditions that the trees experience are completely opposite. Comparing the two, it is clear to see the impact that open land has on the health and size of a mature tree. The caged trees near Washington Street are stunted in comparison to those in the burial grounds. As mentioned in the fifth chapter of Spirn’s Granite Garden, Life, these trees are most likely suffering from the ‘teacup’ syndrome, where “in wet seasons, accumulated water sits in tree pits, unable to drain, and tree roots rot…[and] in drought, roots cannot penetrate compacted subsoil to reach ground water” (Spirn 191). Their full potential can never be reached due to the limited resources that they have access to. But despite this double-edged sword, they still are able to overcome several constraints that have been installed to control them, a true testament to the power of natural processes. Meanwhile, the natural processes in the graveyard show their power by rebelling against the order and uniformity that society tries to implement. The crookedness of the tree trunks contributes to the chaos and, frankly, the more natural aspect of a historic site.

The most blatant use of artificial greenery is located at the 45 Province Street apartment complex in Figure 7. Pot after pot of bamboo is lined up along the front side, a vibrant green even during the winter months. This obviously imported species requires constant maintenance and a lot of water—making it a rather expensive aesthetic. The high concentrations of plant life around the historically significant sites, and even in front of the newly renovated apartment complex, demonstrates the importance of plant life as seen by the residents and the city: the amount of greenery in the area directly correlates with the value and significance of the property. But in spite of all the energy and money that the city puts into plant maintenance, in the end natural resources ultimately make the final decision on the aesthetic aspect.

Figure 7: the front side of the 45 Province Street complex.

Figure 7: the front side of the 45 Province Street complex.

Light and Shadows

The sunlight repeatedly tries to hit the pavement but buildings stand their ground, covering their neighbors in shadows. But still the sunlight is able to influence the six-story-high trees, forcing them to visibly shift their direction of growth in search for a source of light. The larger trees, concentrated in the Granary Burying Ground area, start to lean in the most preposterous ways: it almost seems like they are straining their necks for light—especially towards the back corner of the site, where tall buildings surround the trunks from two sides. Looking at Figure 8, it is clear to see the pattern: all the trees seem to be reaching to the left where, ironically, the buildings are significantly lower than the other two sides—at almost half the height. On the fourth side lies the entrance to the burial grounds, which is relatively open space, but directionally speaking the low buildings lie on the west-facing side, which seems to take precedent.

Figure 8: slanting trees on a search for light in the Granary Burying Grounds.

Figure 8: slanting trees on a search for light in the Granary Burying Grounds.

While recent snowfalls are cleared out of the walkways and streets almost instantly—for the sake of pedestrians and cars, the thin white layer remains untouched in the tiny portions of greenery. In larger areas such as the Burial Grounds, it is easy to spot the melting patterns that arise due to the concentrations of light and shadow. The left side of Figure 9 happens to be the west side with the lower buildings, as mentioned above, while the right side is greeted with a wall of towering buildings from the east. As the sun rises in the east, the structures on the right block sunlight and warmth to the opposite side, leaving the western area in shadows for a significant portion of the day. Come sunset, the lower buildings allow a bigger percentage of light to hit the right side of the graveyard, thereby melting some of the accumulated snow. The path of the sun and the different building heights create an imbalance in sun exposure, leading to this uneven melting pattern.

Figure 9: a panoramic view of the burial grounds, emphasizing the melting patterns of the snow.

Figure 9: a panoramic view of the burial grounds, emphasizing the melting patterns of the snow.

Shifting back to the Irish Famine Memorial plaza, on the leftmost side of Figure 10 in the front, the closest tree is a puny sapling compared to its neighbors: tiny in diameter and short in comparison. In fact, there is a pattern: the size and height of the trees gradually decrease going down the row. It seems that the city intended for all of these trees to be the same size, working off of the uniform aesthetic again, but some natural influence ultimately overruled this decision.

From the row of uneven trees, I arrived at the conclusion that access to natural resources plays a role in this lack of uniformity. The radical change in size implies that the closest tree has been recently planted. One can only infer the cause of death for the previous occupant, but the most likely suspect is light, or the lack thereof. During certain parts of the day, shadows are cast on the little metal grate, leaving the growing tree with little to no sunlight.

Topography

Just as the map in Figure 2 indicates, the Granary Burying Grounds have been around since 1635—predating the landfill project by centuries. Located at the base of the old Beacon Hill, hints of a slope are visible—traces of what used to be. Barely noticeable in Figure 10, this subtle slant is a constant reminder of how natural processes and the history of this site play such an important role in the development of the surrounding neighborhood. Even something as small as this incline will last forever in the topography of the cemetery.

Figure 10: a slight hint of a slope can be seen following

Figure 10: a slight hint of a slope can be seen following

the cobblestone path to the rear of the graveyard.

Conclusion

Despite the many constraints set up by man with the intentions of domination, nature has been able to challenge each of them. And through the years, even as society continues to advance and constantly attempts to control the nature that surrounds it, natural processes will always play a significant role in the development of the city.

Sources:

- Figure 1:Krieger, Alex, and David Cobb. Mapping Boston. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1999.

- Figure 2: Lamb, George. “Plan of Boston: Showing Existing Ways and Owners on December 25, 1635.” Norman B. Leventhal Map Center: Boston Public Library, 1635. http://maps.bpl.org/id/10923

- Spirn, Anne Whiston. The Granite Garden, Urban Nature and Human Design. New York: Basic Books, Inc. 1984.