Walking through Fort Point, it initially appears to be devoid of natural processes: a desolate outcropping of brick in the middle of an asphalt expanse. This incorrect, instant assumption of a disconnect between city and nature is widespread. In The Granite Garden, Anne Whiston Spirn comments that “the belief that the city is an entity apart from nature and even antithetical to it has dominated the way in which the city is perceived” (Spirn, 5). Upon closer examination of Fort Point, it is clear that it is impossible to fully extricate natural processes from the city and its associated human processes. In fact, Fort Point has a rich interaction with nature, although this interaction is not always obvious. This interaction with nature is readily apparent in the trees on the site. Fort Point has a number of trees, the shape and location of which illuminate the work of natural processes. Summer Street is Fort Point’s main thoroughfare. It is raised above the rest of the district and is lined by tall, imposing brick buildings that date back to the early 1900’s. These buildings reinforce the stereotype about they city and nature that Spirn laments. Surely, it is impossible for natural life and these buildings to coexist. However, at the base of these formerly industrial structures are trees. They’re hard to notice, on account of the winter, but they are there, and they provide excellent clues to the way in which the sun interacts with the area.

|

|

Above, on the left, is the North side of Summer Street. On the right, the South side. Clearly, the trees are very different in size. One plausible explanation is that they were planted at different times or they are different species. Neither of these are the case, however. Both appear to be the same species, and as a result of both sides being planted with multiple trees of the same species and size, the entire street was likely planted at the same time. The actual explanation for the disparity in size is the sun. As can be seen in the pictures, which were taken around noon, the South side of the street does not receive any direct sunlight, whereas the north side is almost receiving sun. It is important to note that during the summer, when the trees have leaves and will be growing, the sun, being higher in the sky, will easily reach the North Side trees, and probably hit the South side trees. Because they receive significantly more sunlight per day than the the South side trees, the North side trees are much larger. Sunlight does not only have to get over buildings to reach trees. This can be seen in the alleys between Congress Street and Seaport Boulevard.

In these alleys, the trees grow into the alley, away from the buildings. Again, this is because of the available sunlight. These alleys, as can be seen in the picture, receive sun down their length for a good portion of the day. At a certain point though, the sun will go behind the building on the left, preventing branches from growing towards the building. Looking at these trends, it’s apparent that Fort Point is going to struggle to support mature trees. The buildings are too tall and close together, which prevents trees from getting enough light, hampering their growth. This is an unfortunate artifact of Fort Point’s history. When the area was originally built, it is very likely that the developers did not plan for trees, as they would simply get in the way in a purely industrial district. Yet there are some places where trees can grow, such as the alleys that run Southwest-Northeast. Unfortunately, the main streets, Summer and Congress, are ill-suited to tree life. Not only is the sunlight poor, but all the trees are planted in cutouts in the sidewalk, which fosters “teacup syndrome” in which the trees drown because water cannot drain from the hard picked earth in which the trees are planted (Spirn, 178). The importance of proper growing conditions is evidenced by two trees growing in a patch of open soil between the sidewalk and a retaining wall at the end of Summer Street, above A Street. These two trees have much better soil and access to sunlight, and it shows.

It is common knowledge that trees do not grow well on the North face of a building, which means that without site specific analysis, the observations about trees are too general to be of any help. Therefore, the observations will be analyzed with the following question in mind: what are the consequences are of Fort Point being a poor environment for trees? Spirn laments the loss of mature trees in American cities, observing that without them, “the street, sidewalk, and adjacent buildings feel much hotter, the air grittier...seasons pass unheralded; property values of adjacent residencies decline” (Spirn, 171). With Fort Point, it’s not just that it feels hotter or grittier. There is an aesthetic component as well that makes Fort Point harsher. Without the tempering nature of trees, cold days seem colder and hot days hotter. In this regard, Back Bay is in direct contrast with Fort Point. This doesn’t bode well for the development and inhabitance of Fort Point. People are not going to want to live in a region that seems as if it doesn’t want to be inhabited. Fort Point has just that feel. This analysis reveals an excellent starting point for public development of Fort Point in order to increase development: designing a more habitable ecosystem for trees. As alluded to above, a prime factor in a site’s livability is its climate. Fort Point has two very distinct microclimates, largely due to the way that the sun hits the site. These two states are cold and hot. The cold can be found in the shade on the north face of buildings, as there is little to no direct sunlight. Another example of this is in the small alleys between buildings. These alleys are small and not marked on the map. Because they’re narrow, the sun never heats them up, leaving them noticeably colder than the exposed areas. Walking from one of these alleys into the sunlight, it is not uncommon to go from uncomfortably cold to uncomfortably hot. At first, one would think that is was due entirely to the sunlight impinging on one’s person. However, the effect of the buildings has to be taken into account as well. The brick that the buildings is made of is an efficient absorber and emitter of solar heat. In this way, the buildings create their own microclimate in the area immediately around them. Evidence of this was found in front of the Children’s Museum on Congress Street.

|

|

The left picture is from in front of the Children’s Museum. Even though the area is relatively open and gets prolonged sun exposure during the day, there was a snow pile there. Meanwhile, in the picture on the right from the north side of Summer Street, the snow is gone. The biggest difference between these sites is their proximity to buildings. This difference explains the difference in microclimate, even though both are in direct sunlight. There is another possible explanation for this observation, though. It could be that the buildings are radiating heat because they have heating systems. In reality, the microclimate in the proximity of buildings is influenced by both factors. However, by looking closely at the picture of Summer Street, where the far side of the street has snow on it, it is apparent that radiation of solar heat from buildings likely plays a larger role than the buildings’ heating systems do. Fort Point, being located in South Boston, is surrounded by parking lots, open space, and the ocean. These large, flat expanses provide the wind an uninhibited run at Fort Point. Outside of Fort Point, the wind comes from one direction at a time. Inside, however, it seems to come from all angles at the same time, swirling around the buildings (Spirn, 57). Congress and Summer Street, with their wide, straight expanses, are essentially wind tunnels. When the wind blows from the Fort Point Channel or Convention center, these two streets are rendered nearly impassable. Unfortunately, when the wind blows from the ocean or southwest, conditions are not much better. The alleys between Seaport Boulevard and Congress Street allow the wind to get to Congress Street without much resistance. In this scenario, the wind also comes down over the buildings onto Summer Street, creating a cyclical draft system as illustrated by Spirn in The Granite Garden (Spirn, 57). Neither case is enjoyable. The wind scours the landscape, making Fort Point feel even more desolate than it is. What do these different microclimates mean? The microclimate of an area is of primary importance when it comes to buildings and their comfort. For example, an apartment that faces south and receives full day solar radiation is going to be warm in the winter, and sweltering in the summer. On the contrary, a property that faces one of the small alleys will be cold in the winter and cool in the summer. Obviously, neither situation is necessarily better than the other; it is up to the buyer or inhabitant to decide which they prefer. It seems that Fort Point is being developed and inhabited in a patchwork manner. These microclimates could certainly be one reason why this is the case. No area can be perfect in all weather and temperature conditions, but knowledge of the microclimates and why they exist is an important tool for someone doing something as complex as buying property or something as simple as walking through. So far, the only natural processes that have been covered are those in which humans are passive observers, and in some cases, victims. However, there is a more active relationship between nature and humans that must be explored.

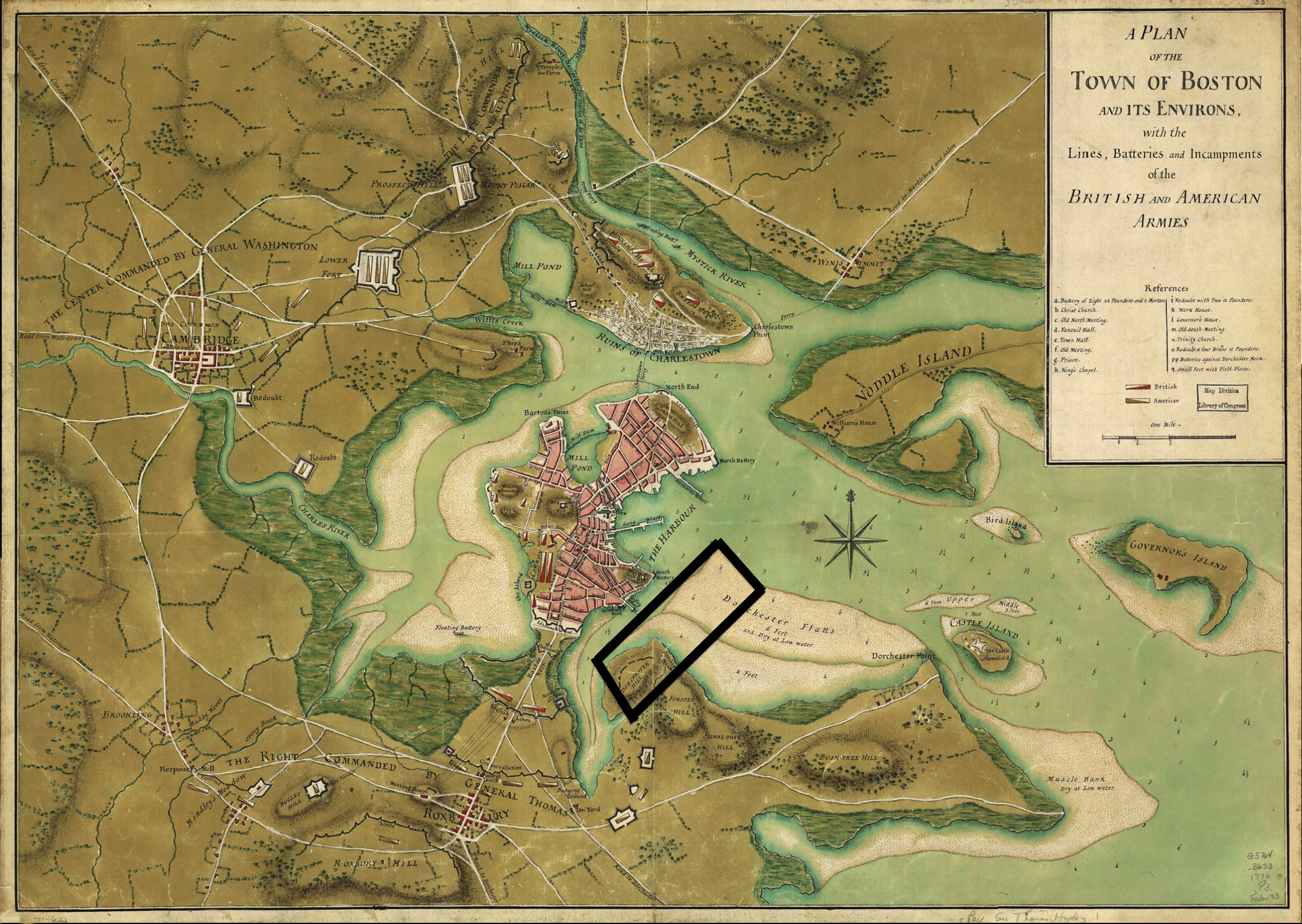

A Plan of the Town of Boston and Its Environs

A Plan of the Town of Boston and Its Environs

The map of Boston above, from 1776, shows a very different Boston than we know today. Fort Point didn’t exist back then. Instead, it was the Dorchester Flats. At some point, Dorchester Hill, Forster Hill, and Signal Tree Hill were leveled to fill the flats and create land that could be developed. This filling represents a human pushback against the thousands of years of natural processes that formed Boston as it once was. This isn’t to say that nature didn’t push right back. Spirn gives us insight into this pushback: “in coastal cities like Boston, half the downtown may have been constructed on filled land, whose stability depends upon its contents and length of time it has been in place” (Spirn, 100). The settling of filled land can be a huge problem. If buildings are built on filled land before it has settled, they can be seriously damaged. Luckily, this isn’t the case in Fort Point, but minor damage, such as cracks in buildings, demonstrates that settling has likely occurred since the buildings were constructed.

|

|

|

|

In Fort Point, there are four buildings with easily observable cracks in their exteriors. While some may believe cracks to be a logical vestige of old brick buildings, and unworthy of analysis, this is not necessarily the case. These cracks are possible evidence of settling of the material used to fill Dorchester Flats. Unfortunately, it is not possible to know when these cracks first showed up or whether they’re still propagating. It’s possible that the fill settled ten years after these buildings first went up. It’s also possible that in the last couple years there has been erosion of the substrate and that these cracks pose a risk to the buildings that they inhabit. One would hope that the former scenario is what is happening here. Without more information though, it’s almost impossible to know. Determining the origin of these cracks and their impact on building structure is beyond the scope of this analysis. Therefore, analysis will only be conducted on the fact that said cracks exist.

A Plan of the Town of Boston and Its Environs A Plan of the Town of Boston and Its Environs

|

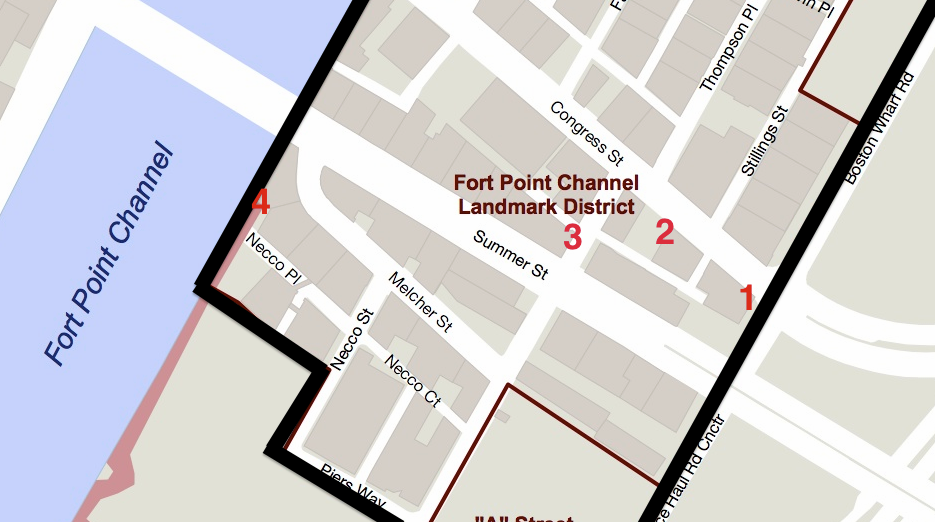

Fort Point Channel Landmark District And Protection Area Fort Point Channel Landmark District And Protection Area

|

As can be seen in the historical map, there is a line in the middle of Dorchester flats. This represents a change in depth of the submerged flats, with the portion closer to Dorchester Hill being shallower than the other part. Looking at the map of Fort Point with the sites of the cracked buildings marked, it is apparent that the line that connects the four buildings is similar in shape to the line on the historical map. This raises the question of why settling only occurred on this line between depths. This could be a result of the progression of the filling of Dorchester Flats. If the flats were only initially filled up to the line that demarcates the change in depth and then later filled entirely, it’s possible that there was poor adhesion between the two sections and that at one point, they settled along this “fault line” of sorts. Natural processes have shaped Fort Point and Fort Point’s inhabitability in profound ways. The question we must now ask, is whether or not developers and residents will stand for these interactions with nature, or if they will seek to change these natural processes. Across the street from the two trees in the retaining wall, there is a new building going up. A building even taller than the tallest building on Summer Street. When it is completed, it will cut down on the amount of light that the trees on Summer Street can get. While the current trees may be sufficiently established to continue to thrive, future trees may never achieve sustainable size. One building could forever prevent Summer Street from having beautiful, fully developed trees. In this way, one developer could have dictated the natural processes of this area for long time. So often, it seems that development occurs without natural processes in mind. This will never be overcome until the words that Spirn spoke about the perceived disconnect between city and nature are no longer true, as a result of people noticing and appreciating natural processes.

Works Cited Elkins, James. How to Use Your Eyes. Routledge: New York, NY. 2000: pp. vii-xi, 12-19, 28-33, 170-175. Fort Point Channel Landmark District And Protection Area. Digital image. Fort Point Channel. City of Boston, n.d. Web. 1 Mar. 2013. http://www.cityofboston.gov/Images_Documents/Fort%20Point%20Channel%20District%20Map_tcm3-13573.pdf. A Plan of the Town of Boston and Its Environs. Digital image. 90.9WBUR. WBUR, 1 May 2012. Web. 1 Mar. 2013. http://www.wbur.org/files/2012/04/boston-17761.jpg. Spirn, Anne Whiston. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design. Basic: New York. 1984.