From a distance, Fort Point looks like a block of factories on the verge of collapse. Upon walking the streets of Fort Point, it becomes clear that while the district probably once faced such a fate, the narrative has been rewritten. The brick buildings have been restored. Tech companies, restaurants, and law firms inhabit them. What happened here? Why the redevelopment?

Map data ©2013 Google, Sanborn

Map data ©2013 Google, Sanborn

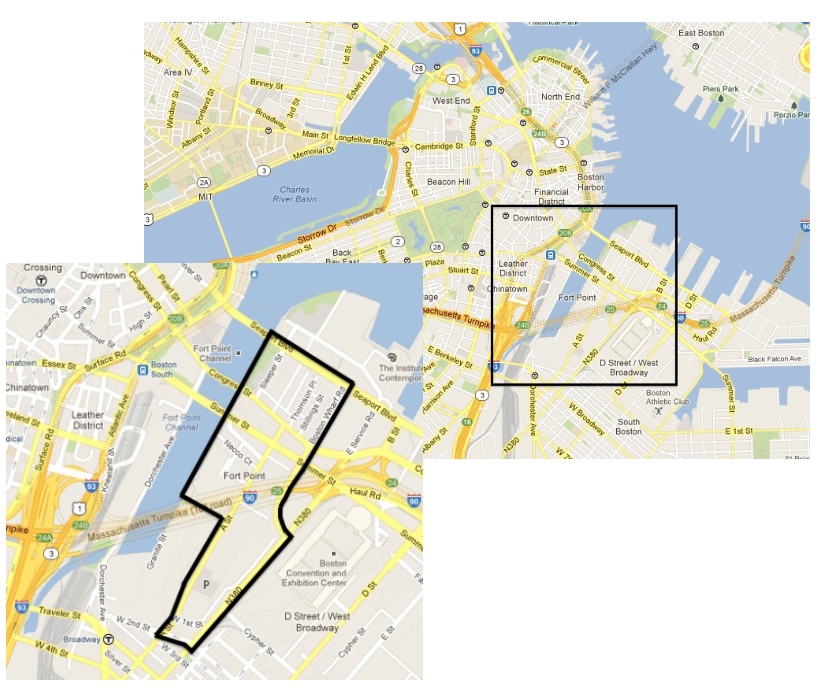

When I walked Fort Point, the boundaries felt obvious. Other than Summer and Congress Streets, which run through the middle of Fort Point, the area is dense. Keeping Grady Clay’s Up Close and his talk of breaks, or “visible switches in the direction and/or the design of streets” in mind, I chose boundaries that “broke” this characteristic building and street density. The buildings are close together with weird alleys running between buildings in weird ways. The first boundary is a natural one, the Fort Point Channel. Next, to the northeast is Seaport Boulevard. The boulevard is four lanes across, and between it and the next buildings, are large parking lots. In concert, the boulevard and parking lots mark the northern end of the density. This same reasoning was employed in picking the Southeast boundary. Again, Boston Wharf Road and N360 mark the end of brick buildings and the beginning of parking lot and open space. Fort Point is frequently considered to include the Proctor & Gamble plant on Dorchester Ave and W 2nd street. However, I’m choosing not to include it because I’m focusing on restoration and the redevelopment of the area. To cut the plant out, on the southwestern side, my boundary is made up of W 2nd, A Street, and Binford Street. Interestingly, this district is made up entirely of old brick buildings. There is little variation in building style, with the exception of the Children’s Museum on Congress Street and two other building on Congress that are both made of a glass, metal, and brick. This stylistic homogeneity gives the impression that without cars, one would have a hard time determining what year it was. Oddly, Summer Street runs over A Street. Why is this so? Was the area originally ocean that was filled or a hill that was leveled? Hopefully, knowing Fort Point’s original geographic features will illuminate its development over time. Surprisingly, Fort Point seemed deserted. I visited at 4pm on a Sunday during a snowstorm, so this can be partially expected, but I got the impression that no one lived here. The Courthouse T stop on the Silver Line on Seaport Boulevard, one of the nicest stations in Boston was silent, with an empty, running escalator the only indication that people are supposed to be there.

Thinking back to Close Up and the anecdote about the interesting techniques that Clay and his colleagues used when studying a changing Chicago, such as counting footprints in freshly fallen snow to measure neighborhood density, I decided to keep my eyes peeled for unusual clues to determine the land use nature of Fort Point . Luckily, I happened upon one at Dunkin Donuts. The Dunkin Donuts on Congress Street was open for normal hours during the week, but only until 2pm and 3pm on Saturday and Sunday. This points towards Fort Point being a largely commercial area, but further exploration is needed, as I saw multiple apartment lobbies throughout the area. Fort Point has an almost binary existence: old building with new businesses. Apartments seemingly without people. A high density of buildings in a sea of asphalt. This binary nature raises a myriad of questions. Why weren’t all the buildings razed at one point to make for more parking lots? When will this area be bustling? Was Fort Point developed too fast? Answering these questions will illuminate both the history of the area, and at the same time, the future of Fort Point.