Map data ©2013 Google, Sanborn

Map data ©2013 Google, Sanborn

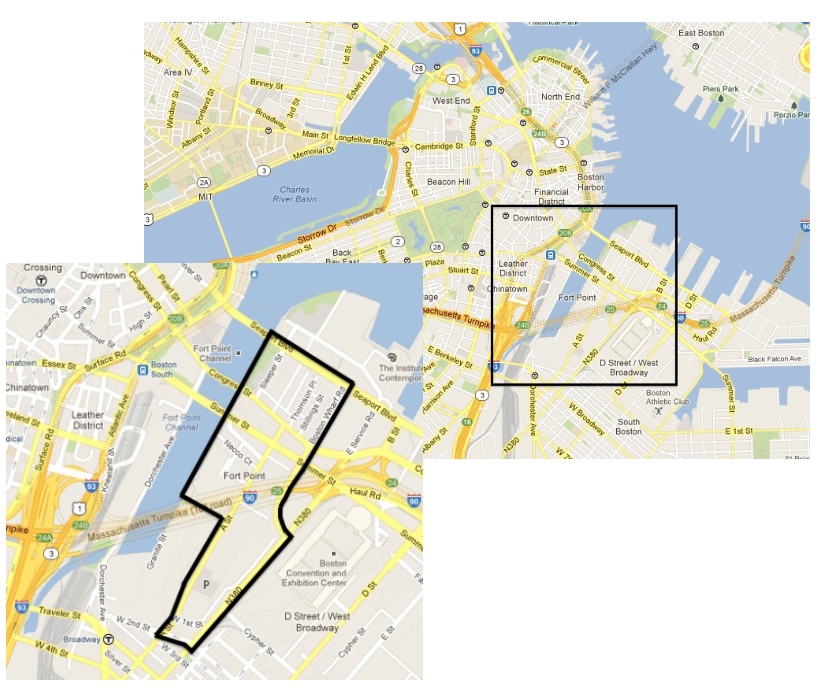

Fort Point has come a long way from its original existence as the Dorchester Flats. Today, it is the process of being redeveloped as “the innovation district,” a zone meant to compete with such meccas of technology as Kendall Square and Silicon Valley. Will it ever reach the same level? It’s too early to tell. However, it is clear that Fort Point is a versatile piece of land that has grown in spurts from the moment it was filled in. As opposed to some districts that grow gradually over time, transitioning between land uses multiple times, Fort Point’s history has been characterized by long periods with limited change interspersed with periods of rapid change. This is especially pertinent today, as Fort Point is currently undergoing such a change. By investigating and understanding this history of rapid, short bursts of change, this paper hopes to more accurately anticipate what the future holds for Fort Point. The first step in examining the history of Fort Point is to examine Dorchester Flats and the site before the land was solid.

Page

Page

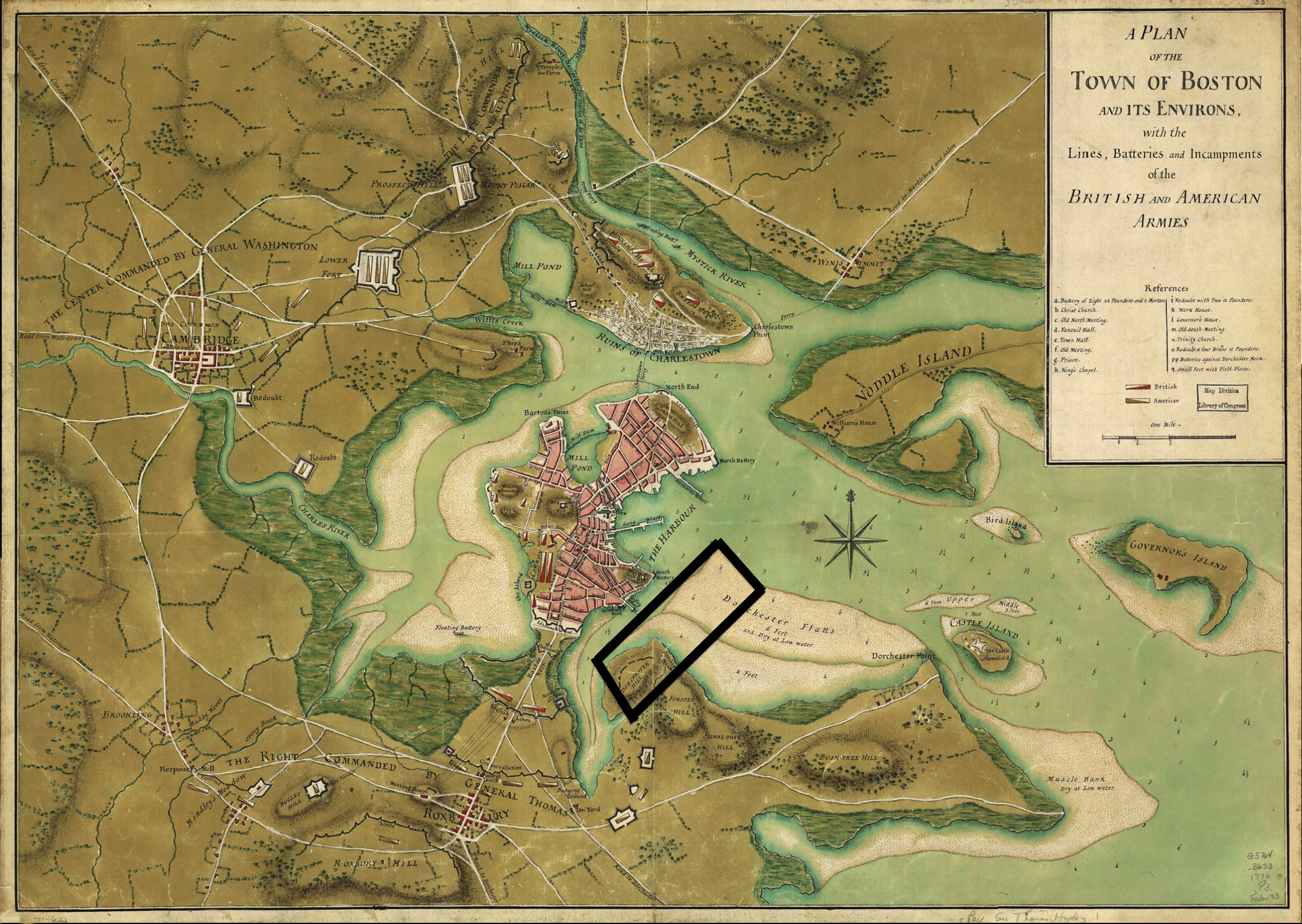

The map above, from 1776, shows an unfamiliar Boston. The reason for this is because the filled land that much of Boston rests on today has yet to exist. This is the case with Fort Point. A black box has been added to the map to show where Fort Point is today. This map is not helpful on its own, but when looked at in conjunction with a map of the area after the land was filled, conclusions can be drawn.

Boynton

Boynton

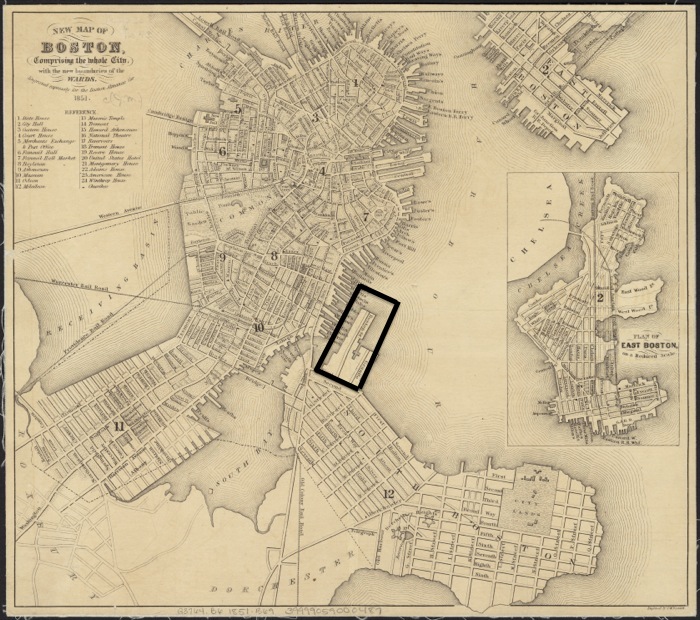

Here, in a map of Boston from 1851 by George Boynton, we see for the first time, Fort Point. However, that is not the only reason why this map is valuable piece of the puzzle. It is valuable because it gives insight into why Fort Point exists. The 1776 map has one prominent wharf. The 1851 map has a myriad of wharfs. Clearly, the shipping industry took root in Boston between 1776 and 1851. Sam Bass Warner Jr. speaks of this boom in trade in Mapping Boston, noting that “world trading carried Boston to its Pre-Civil War mercantile peak” (Warner, 7). Fort Point was filled in to capitalize on this burgeoning trade industry. This was Fort Point’s first rapid change: coming into existence. Like its later changes, this change was driven by the economic climate at the time. Fort Point doesn’t appear to be the home of any economic activity yet in this map, but this would change over the next thirty years. The next glance into the history of Fort Point comes in 1884 by means of a Bromley map. Instead of using it to only look forward, we can use this map to look back in time and make more sense of the filling of Fort Point.

1884 South Boston Combine Final

1884 South Boston Combine Final

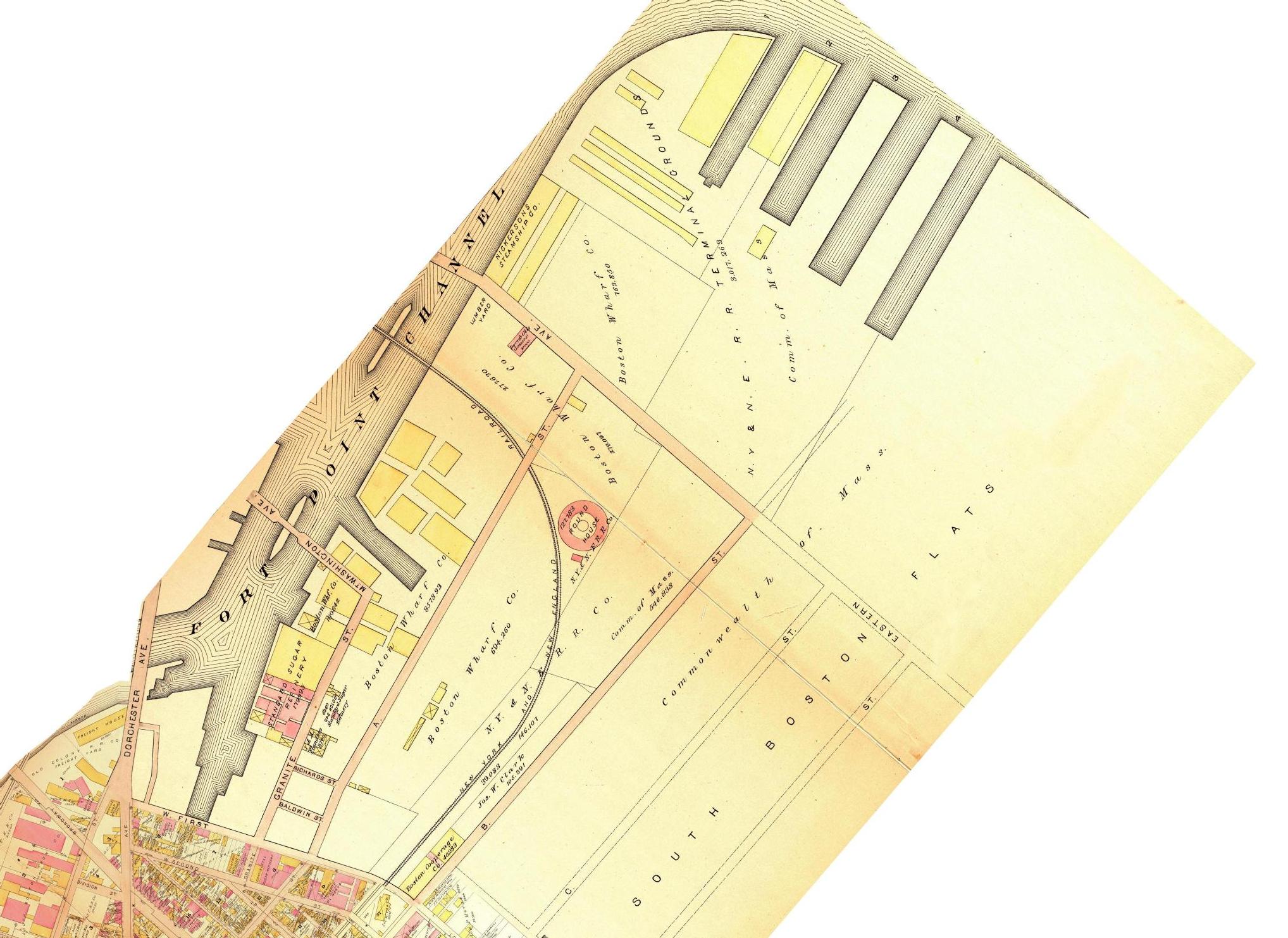

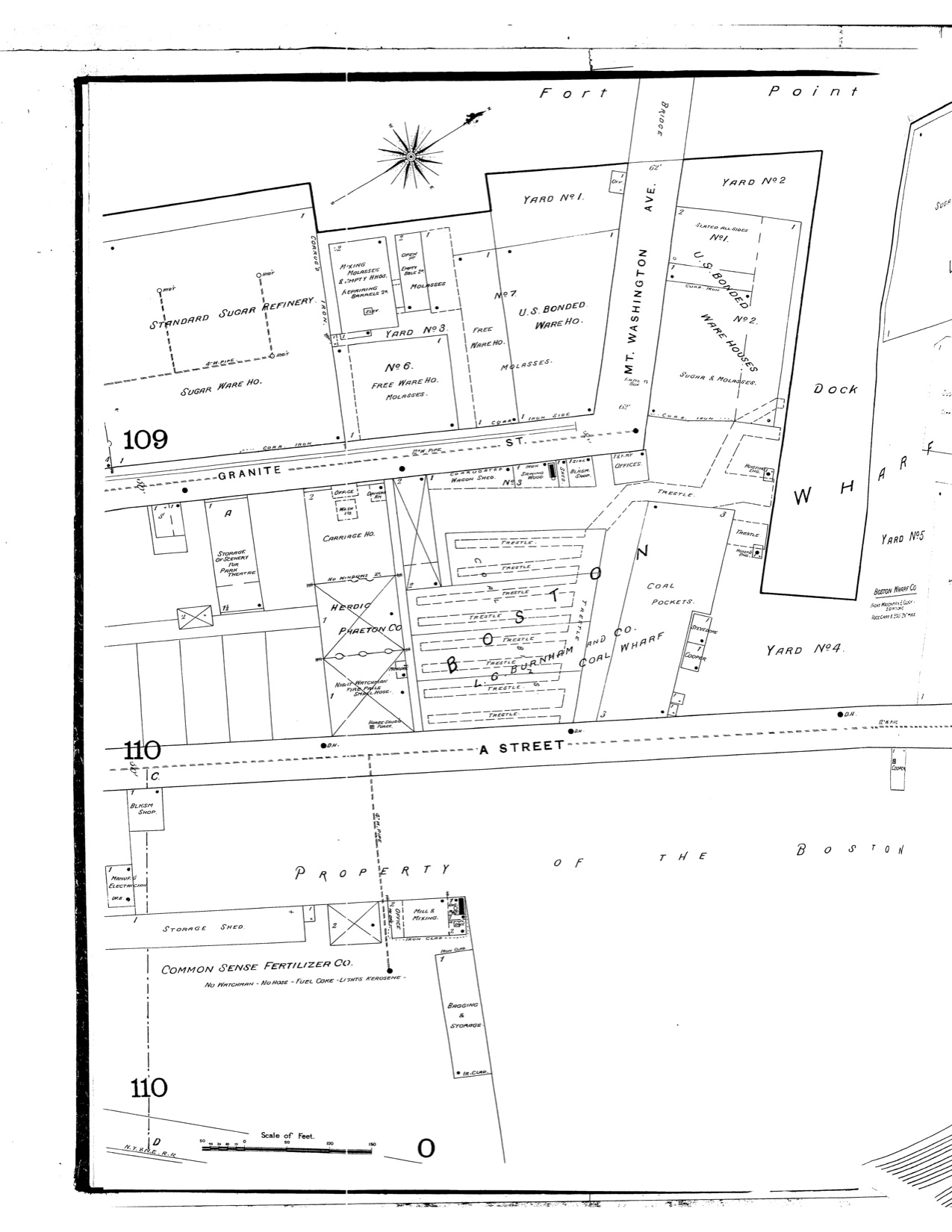

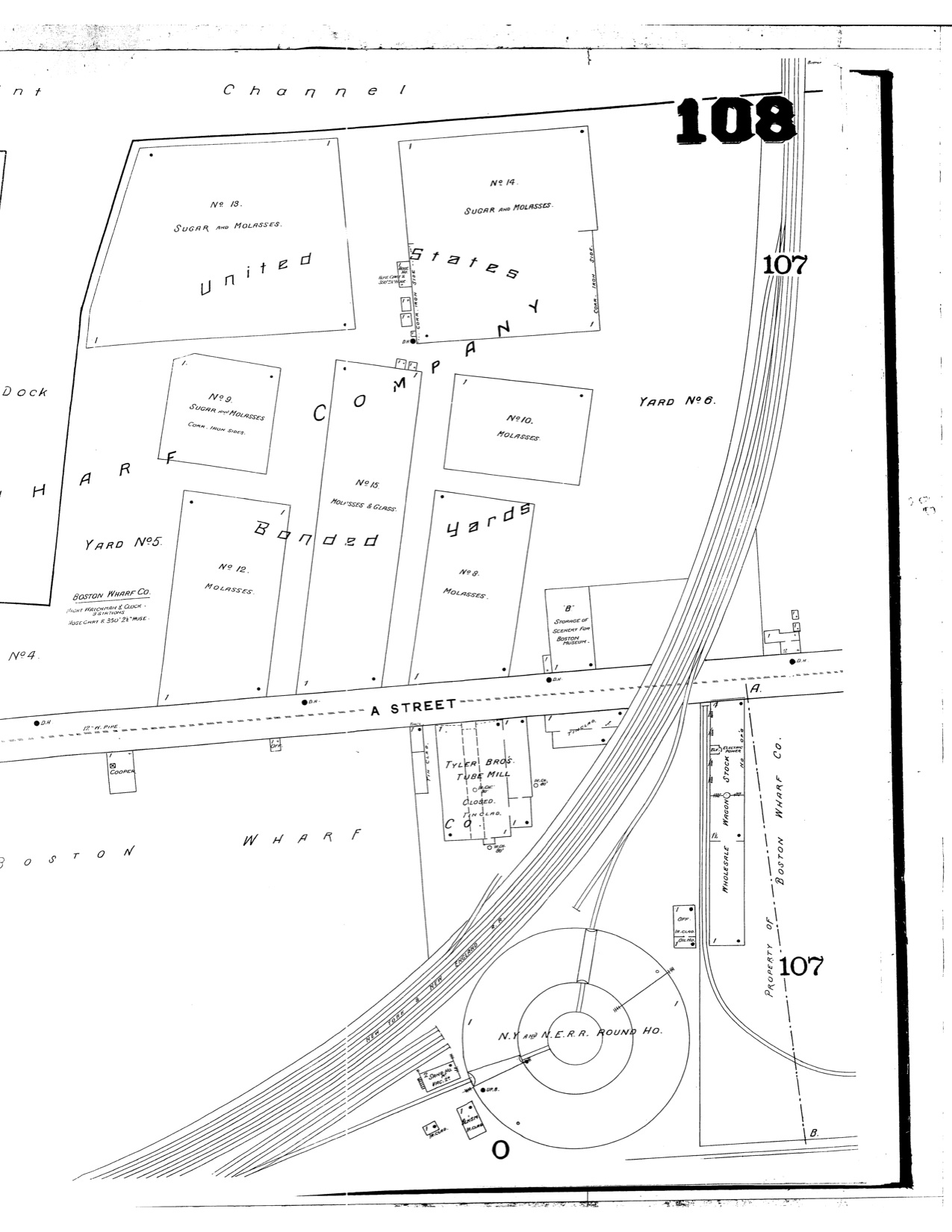

To tease out this information, we have to look at the ownership of the land. There are only two landowners in the map above: The Commonwealth of Massachusetts and the Boston Wharf Company. By looking back at the original filled land, one can see that all of it is owned by Boston Wharf Company. The explanation for this is that the Boston Wharf Company filled in Dorchester flats in between 1776 and 1851, and therefore, owned the land. Such an action demonstrates what a different time the 19th century was. Today, it is hard to imagine that a private company would be permitted to fill in the ocean to create itself new land in a prime location. It isn’t possible to know what exactly the buildings in the map were used for, with the exception of the Standard Sugar Refinery, but it would be reasonable to assume that they were storehouses or warehouses of some sort. They’re too large to be single-family homes. It is also very unlikely that they were apartments or tenements. It wouldn’t make much sense for the Boston Wharf Company to fill in this land only to build housing. Instead, they would buildings meant to aid in the wharf business. This is an example where examining the name of something, while a simple practice, can be helpful. One feature of 1884 Fort Point that must be noted is the railroad. The railroad revolutionized the movement of goods, making it cheaper and faster to move large quantities of freight. This may be why Fort Point was used for storage in 1884. It is not easy to see in the 1884 map, but the Fort Point channel is narrow: far too narrow for a large ship to navigate. Additionally, the presence of the Mt. Washington and Eastern Avenue bridges would have made it impossible for a ship to enter the channel. This is inconvenient, because the warehouses are right there. Ideally, the wharf and warehouse would be adjacent. This was not an option for the wharves in Boston because of the encroachment of housing. Therefore, the warehouses had to be removed from the wharves. The New York and New England Railroad made this possible. Goods could be unloaded from ships on the wharves in Boston, loaded onto the train, and then unloaded at Fort Point for storage. Common sense might dictate that the railroad hurt the shipping industry, but as this example demonstrates, they might have actually had a symbiotic relationship.

|

|

|

| Boston. Map. 1889. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1885-1888 vol. 4, 1889, Sheet 108_a". Digital Sanborn Maps. http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000002.htm?CCSI=254n. Boston. Map. 1889. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1885-1888 vol. 4, 1889, Sheet 108_b". Digital Sanborn Maps. http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000002.htm?CCSI=254n. Boston. Map. 1889. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1885-1888 vol. 4, 1889, Sheet 107_a". Digital Sanborn Maps. http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000002.htm?CCSI=254n. | ||

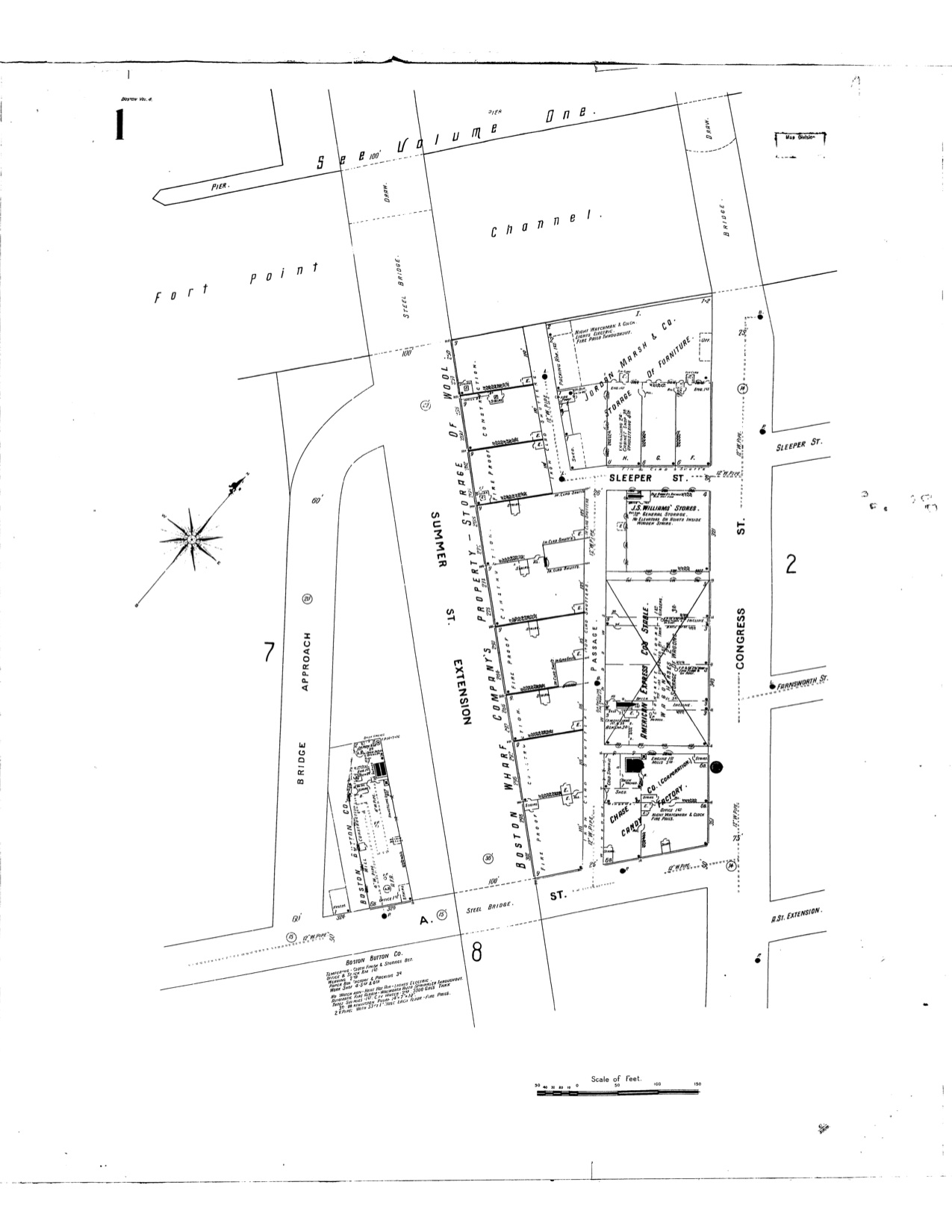

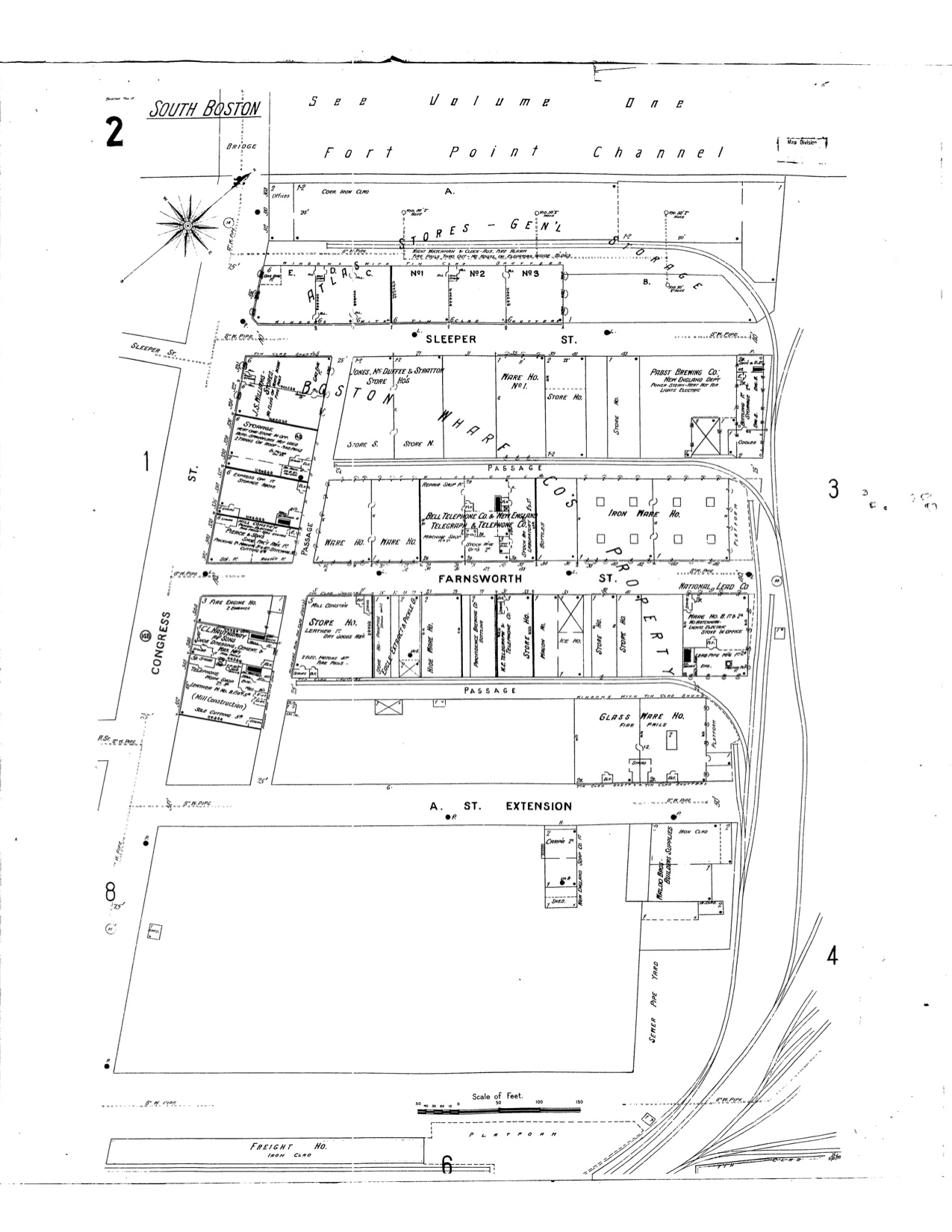

Looking forward only five years, this 1889 Sanborn Map demonstrates significant change and establishes a precedent for Fort Point economic activity: focusing on a certain industry. In the 1884 map, the only labeled business was the Standard Sugar Refinery. Five years later, a large portion of Fort Point is dedicated to sugar and molasses. The land to the right of the dock were turned into sugar, molasses, and glass warehouses. To the left of the dock are more buildings dedicated to sugar. Breaking the trend is L.G. Burnham and Co. Coal Wharf on A Street. Like the filling of Fort Point demonstrated a blossoming shipping industry, the sugar and molasses storage and refinery demonstrate the importance of the sugar industry. One question that the location of these building raise is why a sugar refinery would be located here. The maps don’t hold the answer, but they may contain clues. One such clue is the size of the New York and New England Railroad. What was a one track railroad in 1884 increased to four tracks by 1889. Being in close proximity to such a large rail complex must have been beneficial. It’s possible that raw sugar was imported to Boston by ship, moved to Fort Point by rail, refined into molasses, and then send out, both by rail and ship. The roundhouse in the lower right corner of the right map lends credence to this theory. Roundhouses are used to turn trains around. If the trains didn’t need to travel back and forth between the Boston wharves and the Fort Point warehouses and refineries, the roundhouse would be unnecessary. The rail company clearly had a financial incentive to provide for such behavior by the sugar companies. Streets begin to appear in 1889. In the rightmost map, Congress Street and Sleeper Street appear for the first time. It is in this area that Fort Point begins to diversify. As stated earlier, the reason that the sugar companies were located in Fort Point cannot be know, but the existence of a candy factory on Congress and A Street can definitely be explained by location of the sugar companies. Sugar was not the only industry in Fort Point at the time, though. Around Congress Street were a number of other storehouses, concerned with glass, meat, wool, and cotton. Were these storehouses meant to hold goods before they were transported long distances? Or were they more like stores in the current sense of the word? Based on the American Express Stables being built on Congress Street and the size of the buildings, the correct explanation is likely the latter. A large stable would be needed if all the storehouses needed horses and wagons to transport goods throughout the city. While Fort Point was still in the formative stages in 1889, it was beginning to become a sector of large-scale operations paired with smaller, mixed businesses. The one area in which Fort Point was not mixed, however, was land use. Shifting from 1889 to 1899, the focus of the analysis shifts. Before, the focus was significantly southwest of Congress Street. However, a lack of maps of the area prevents us from continuing in the area. Starting with 1899, Congress Street becomes the center of the investigation.

|

|

| Boston. Map. 1899. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1895-1900 vol. 4, 1899, Sheet 1". Digital Sanborn Maps. http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000008.htm?CCSI=254n. Boston. Map. 1899. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1895-1900 vol. 4, 1899, Sheet 2". Digital Sanborn Maps. http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000008.htm?CCSI=254n. | |

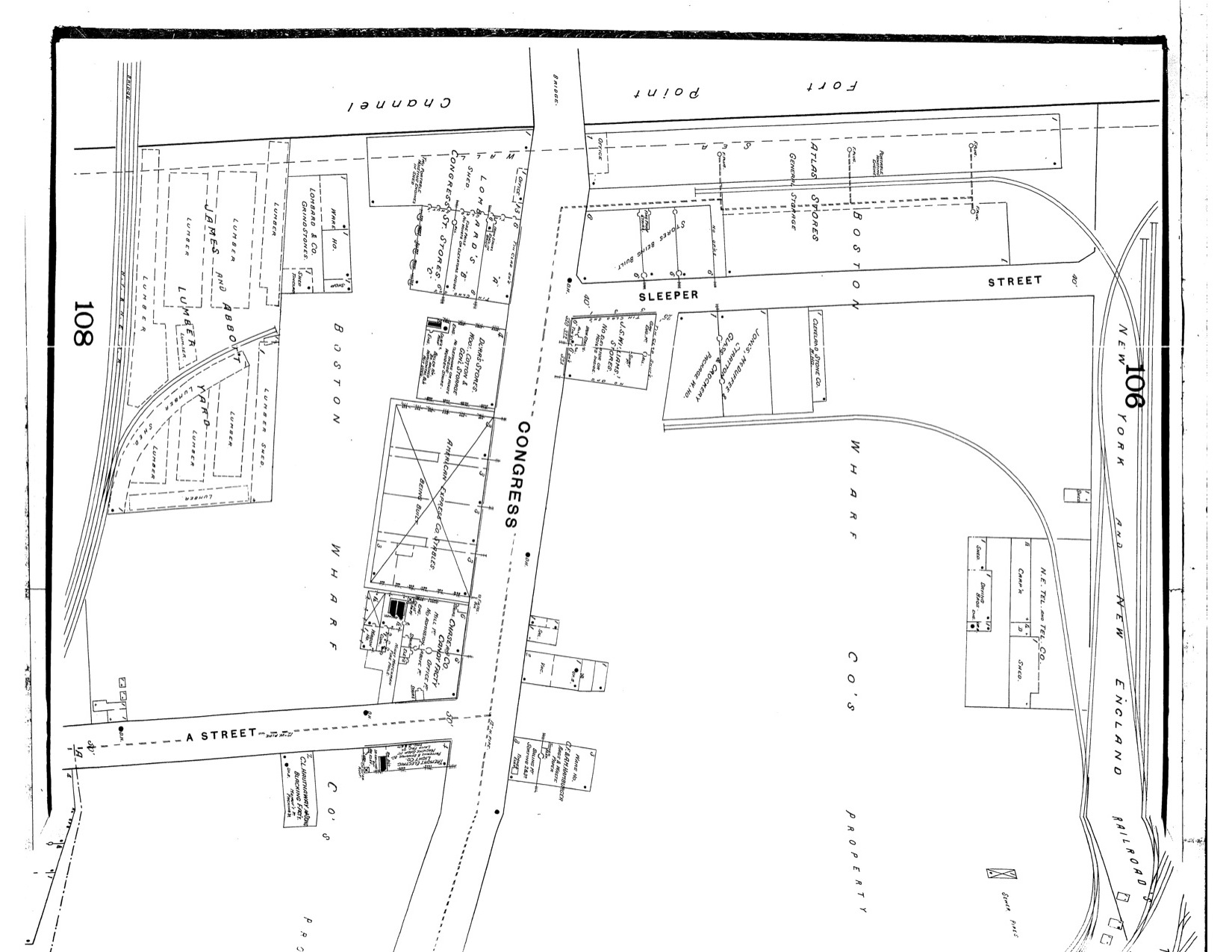

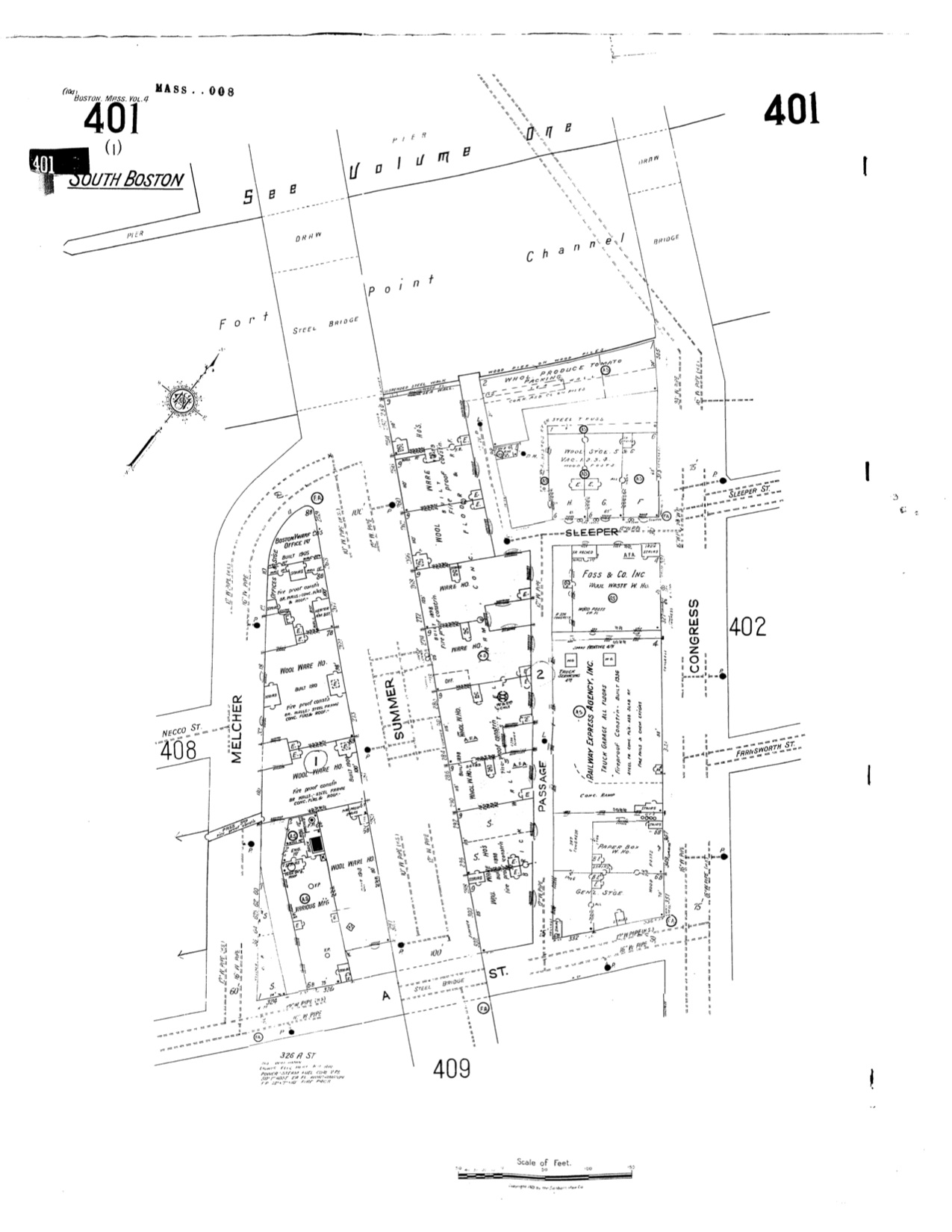

Much like 1889 was characterized by sugar, 1899 was characterized by wool. Whereas the Boston Wharf Company was primarily involved in the leasing of land from 1850-1889, in 1899, it begins to build its own buildings, a series of wool warehouses that lined Summer Street. To make room for these, the lumberyard by the railroad was removed. The railroad was also removed. This is a peculiar occurrence that is hard to make sense of. There is nothing on the map that can help shed light on what happened. Maybe Boston Wharf Company decided that the railroad was no longer the most profitable use of the land. It’s also possible, of course, that Boston Wharf Company had nothing to do with the railroad leaving. Either way, Summer Street was built and Bridge Approach was put in where the railroad once was. More roads were added to the northeast of Congress Street as well, creating a grid system. One fascinating trend that continues from 1889 is the extension of rail lines down these newly laid streets. This was done to make it easier to load trains and save time. The addition of these roads brings up the question of who financed them. Here it is helpful to look to Crabgrass Frontier by Kenneth Jackson. In his book, Jackson says that before the Civil War, property owners would request that roads be repaved, but that they would pay for such improvements. This changed in the 1890’s, though. “By the 1890’s, engineering publications were hypothesizing that well-paved roads, paid for by the city, would reduce the cost of freight-handling, thus encouraging new businesses and reducing the tax rate” (Jackson, 131). Based on the 1899 map, it appears that this reasoning might have been correct. A number of businesses moved into the new lots created when the roads were laid down. It’s important to note that the businesses that moved into these lots likely did not do so randomly. For example, there were two leather warehouses, a hide warehouse, an iron warehouse, and a machine shop, not to mention all of the of wool warehouses. What could explain all of these businesses being in one place? According to Sam Bass Warner Jr., “The same money that financed the building of wharves and ships also funded the building of modern textile mills at river sites beyond Boston. These regional factories with their need for large-scale supply of coal, cotton, wool, and leather remade Boston into a nest of portside warehouses and rail yards, remnants of which survive behind South Station along lower Summer Street” (Warner Jr., 7) This trend is in keeping with Fort Point being largely shaped by external commercial pressures. Unlike some districts, Fort Point was unable to create its own economic trends, instead relying on the prevailing economic wind. For this reason, it is a shame that there isn’t a detailed map of Fort Point immediately after the Great Depression. Because Fort Point was largely at the mercy of the national economic mood, it is reasonable to assume that the Great Depression would have hit the district hard. The Second World War is another reason why a 1930’s map would be valuable. The war served as an incredible stimulus to the US economy, making the years between the start of the Depression and the end of World War Two incredibly formative, especially for businesses and commercial districts. Being able to compare the district after the Depression and then again after World War Two would be interesting and could hold important clues about the development of Fort Point. However, we do not have access to a post-Depression map. We will need to rely on a Sanborn map from 1950 in trying to determine the effects of the crucial period mentioned.

|

|

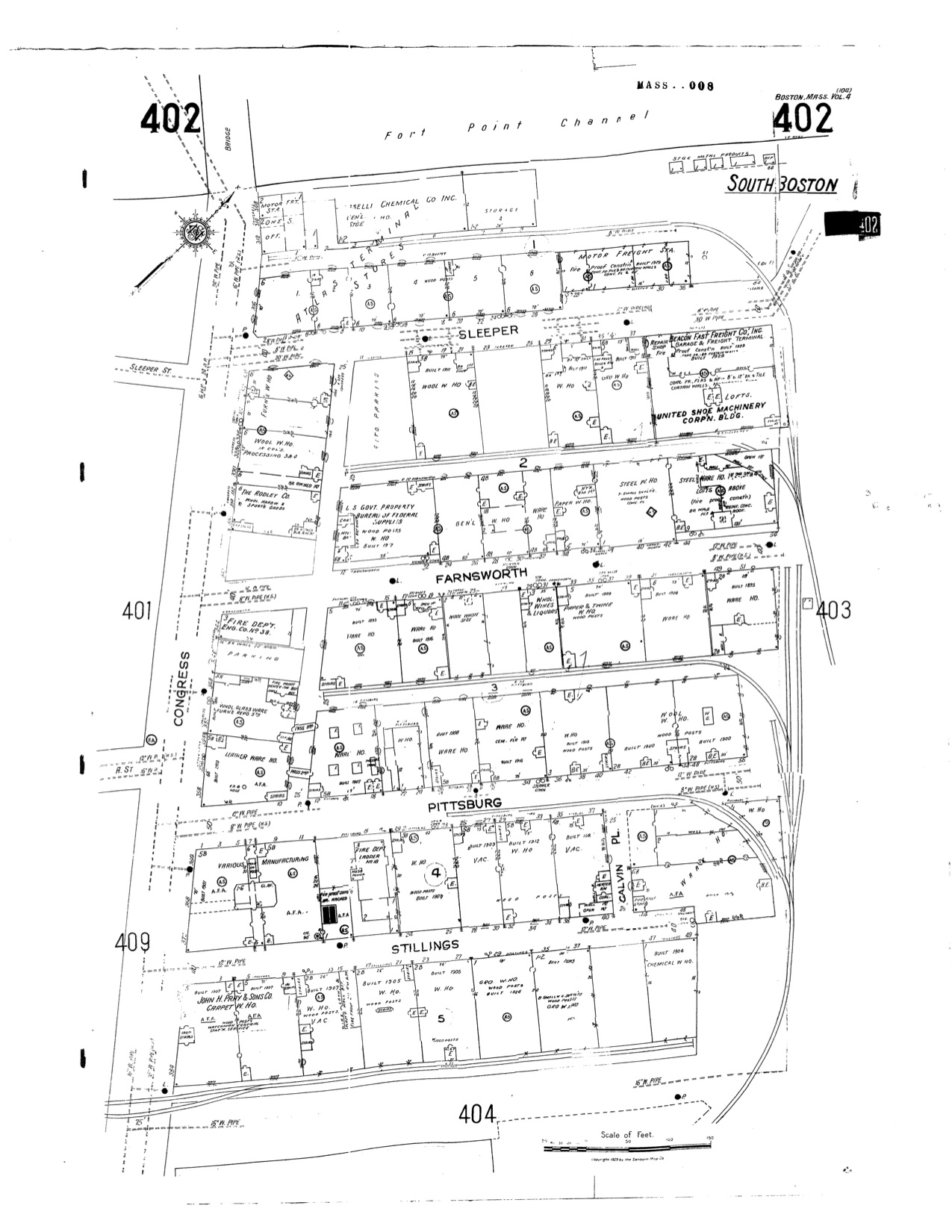

| Boston. Map. 1950. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps,1929-Feb. 1951 vol. 4, 1923-Apr. 1950, Sheet 401". Digital Sanborn Maps. http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000035.htm?CCSI=254n. Boston. Map. 1950. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1929-Feb. 1951 vol. 4, 1923-Apr. 1950, Sheet 402a". Digital Sanborn Maps. http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000035.htm?CCSI=254n. | |

The wool industry emerged from the Depression-War period in seemingly great shape. This observation is based on the increase in the number of buildings dedicated to wool between 1899 and 1950. One explanation for the strength of the wool industry could be that demand for wool increased during the war in order to make soldiers’ uniforms. If this is the case, it is not surprising that wool did well during the period. The problem with a 1950 map if we are trying to determine the influence of the war on the area is that by that time, there had been five years of peace. This was a period of prosperity in the country, as soldiers and factory workers had more money than ever. This could explain why there was a carpet company and liquor wholesaler in the area. People decided to spend their money on items that were previously out of reach of some households. Perhaps even more significant than the impact of the war on the country, though, was the impact of the automobile and truck. Kenneth Jackson describes the impact of the truck, which “even in its primitive form before World War I, could do four times the work of a horse-drawn wagon which took up the same street space” (Jackson, 183). Although it is difficult to discern just what the car and truck did for Fort Point, the replacement of horse-drawn vehicles and the end of the horse-drawn era are readily apparent. What was once the American Express stable on Congress Street was turned into a truck garage. Parking lots appeared on Congress and Sleeper Streets. Two new buildings cropped up: a motor freight station and Beacon Fast Freight Co. Based on the history of Fort Point so far, it would be reasonable to expect the area to forever remain a collection of warehouses and manufacturing. Cataloging the land usage from 1776 to 1950 would have been a waste of time, as the land was solely used for industrial purposes. At some point between 1950 and today, Fort Point changed. It is no longer entirely industrial. Buildings are now being used for commercial

Boston Redevelopment Authority

Boston Redevelopment Authority

These changing land uses can be seen above. What was once the block of wool warehouses on Summer Street is now a block of apartments. What were warehouses on the Fort Point channel is now the Children’s Museum. An old fire station serves as the Boston Fire Museum. The commercial space is being used by tech firms and specialized companies. Slowly but surely, the innovation district that Mayor Menino called for is taking shape. Why did Fort Point change? Where and why did the wool go?

Without additional research, it is hard to know. One possibility is that it has been outsourced to locations closer to the mills that spin it into fabric. The mighty textile mills of New England don’t exist anymore, so it no longer makes sense to have the warehouses here. Mills disappearing is a direct consequence of the changing American economic climate, once again showing Fort Point to be an economic bellwether.

Fort Point hasn’t changed much aesthetically in the last 120 years. However, it would be a mistake to extrapolate this and draw the conclusion that the area hasn’t changed at all. In fact, Fort Point has undergone significant economic change and has shown a remarkable ability to adapt to the economic climate of the era. In this sense, the spirit of Fort Point hasn’t changed. It is for this reason that one must believe that Fort Point has a chance at becoming a thriving tech center. If the area could become a thriving sugar and then wool hub, why can’t it do the same again with tech?

Works Cited

1884 South Boston Combine Final. Map. 1884. The Boston Atlas. 5 Apr. 2013.

Boston. Map. 1950. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps,1929-Feb. 1951 vol. 4, 1923-Apr. 1950, Sheet 401". Digital Sanborn Maps. http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000035.htm?CCSI=254n. 5 Apr. 2013.

Boston. Map. 1950. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1929-Feb. 1951 vol. 4, 1923-Apr. 1950, Sheet 402a". Digital Sanborn Maps. http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000035.htm?CCSI=254n. 5 Apr. 2013.

Boston. Map. 1899. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1895-1900 vol. 4, 1899, Sheet 1". Digital Sanborn Maps. http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000008.htm?CCSI=254n. 5 Apr. 2013.

Boston. Map. 1899. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1895-1900 vol. 4, 1899, Sheet 2". Digital Sanborn Maps. http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000008.htm?CCSI=254n. 5 Apr. 2013.

Boston. Map. 1889. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1885-1888 vol. 4, 1889, Sheet 108_a". Digital Sanborn Maps. http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000002.htm?CCSI=254n. 5 Apr. 2013.

Boston. Map. 1889. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1885-1888 vol. 4, 1889, Sheet 108_b". Digital Sanborn Maps. http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000002.htm?CCSI=254n. 5 Apr. 2013.

Boston. Map. 1889. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1885-1888 vol. 4, 1889, Sheet 107_a". Digital Sanborn Maps. http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000002.htm?CCSI=254n. 5 Apr. 2013.

Boston Redevelopment Authority. "South Boston." Map. Boston Redevelopment Authority, n.d. Web. 5 Apr. 2013.