Map data ©2013 Google, Sanborn

Map data ©2013 Google, Sanborn

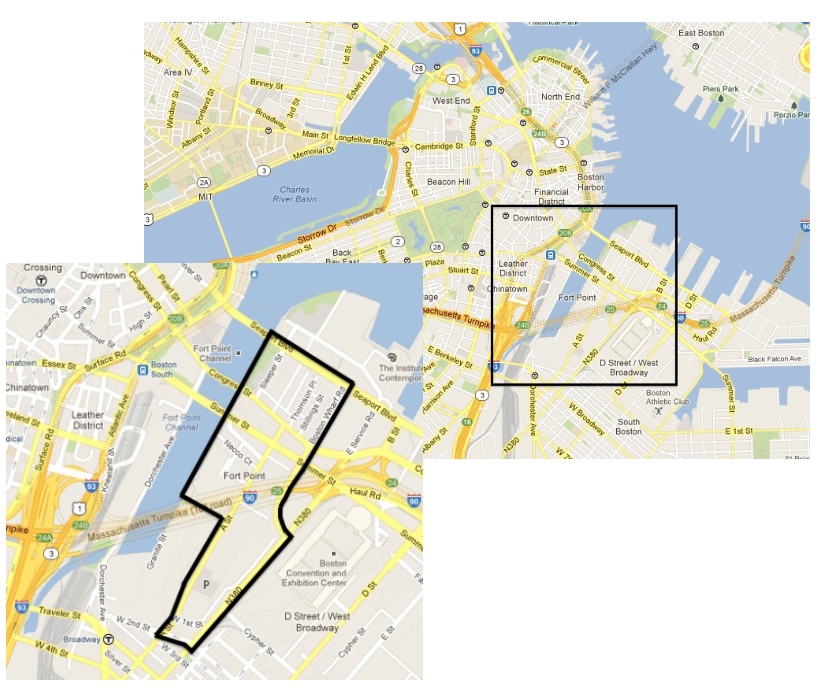

Fort Point was at one point the wool capital of the United States. However, that time has passed. The wool industry has long since moved out of the brick industrial buildings on Congress and Summer Streets. One might have been tempted to draw the conclusion that Fort Point died along with the Boston wool industry and that it was time to start over, as was done with the urban renewal of Boston’s West End in the 1950’s. However, Boston is lucky that such a conclusion was never drawn and that such a plan was never carried out. Fort Point is a seemingly forgotten urban gem in the incredibly rich urban landscape of Boston and serves as a foremost example of appropriate redevelopment. The area can help developers remember that

“it is city dwellers’ shared lifetimes that create an American sense of place. In scale and approach, this is the opposite of the top-down thinking that underlies urban design as grand-scale redevelopment planning practiced by American cities. There the understanding of history is often minimal, the practice often involves vast areas of demolition and new construction” (Hayden, 235).Fortunately, in renewing Fort Point, developers viewed the existing wool infrastructure as a substrate for development rather than a bane to development. Fort Point’s rich history and path to its current existence will not be forgotten, nor should it, because it tells the story of adaptation and success. The first step in understanding how the history of Fort Point manifests itself today is to analyze artifacts and traces, as they are the most readily apparent remnants of the pasts. An investigation of the trends and layers of Fort Point will be more instructive if the artifacts and traces have already been dissected. It makes sense to talk about artifacts and traces in conjunction, because artifacts often double as traces in that they reveal something that once was (“Podcast: Artifacts, Traces, Layers, and Trends"). Let us begin with artifacts. Anne Whiston Spirn defines an artifact as “anything made by human art or workmanship, an artificial product” (“Podcast: Artifacts, Traces, Layers, and Trends"). The original Fort Point artifact is the filled land. This may seem to be an unnecessary distinction, but that is not the case. Someone without historical knowledge of Fort Point would be unable to determine, by walking Fort Point alone, that the area was once the Dorchester Flats. This puts the observer at a disadvantage in understanding the site, as it limits their ability to understand the impact that the Boston Wharf Company, the company that filled the flats, had on Fort Point in its formative years. This artifact acts as a trace in that it evokes the importance of the Boston shipping industry in the development of the city in the early 1800’s. The influence of the Boston Wharf Company is apparent no matter where one looks in Fort Point. The vast majority of buildings were built by the company, and still feature a copper medallion that reads “BW Co.” and the year in which the building was built.

Boston Wharf Company medallion that reads '1907'

Boston Wharf Company medallion that reads '1907'

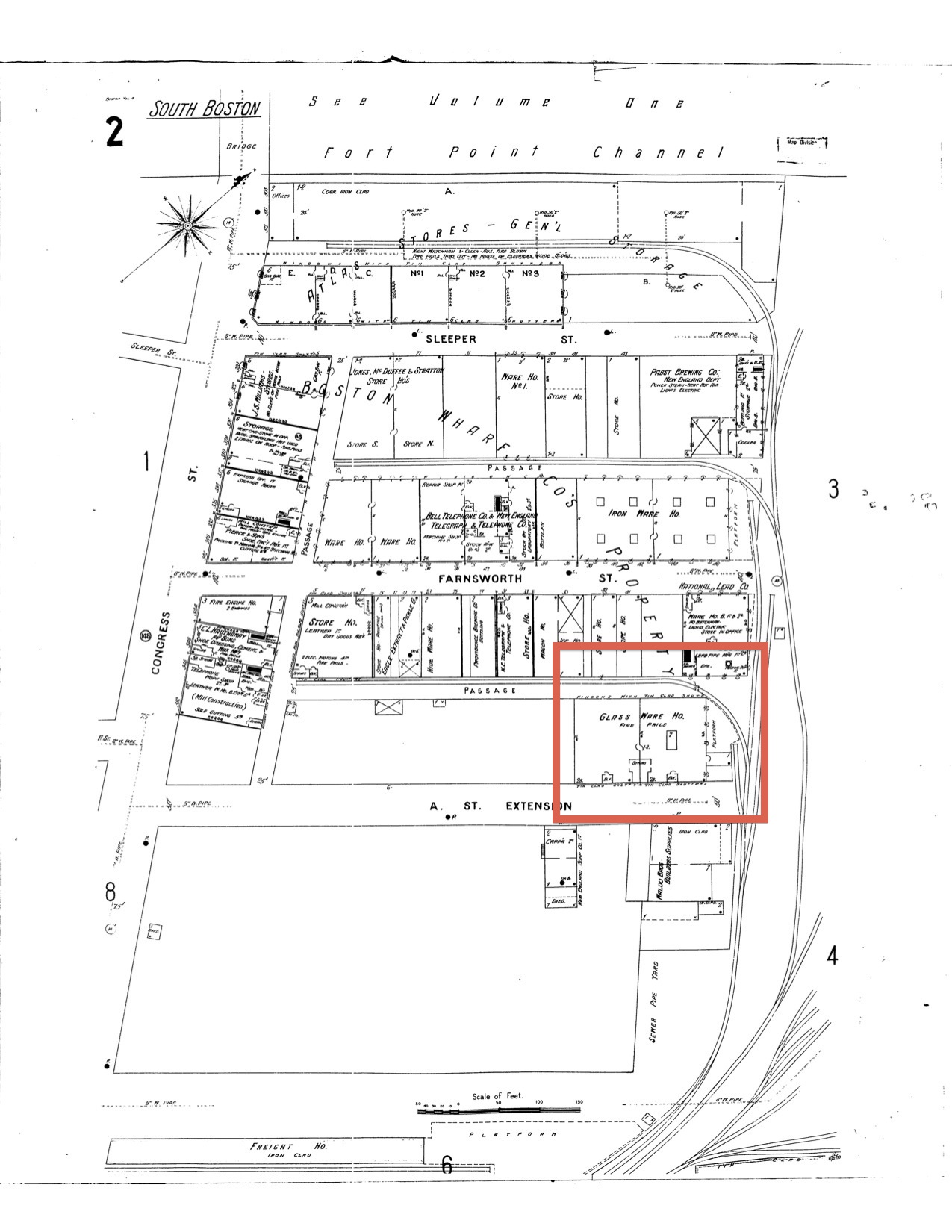

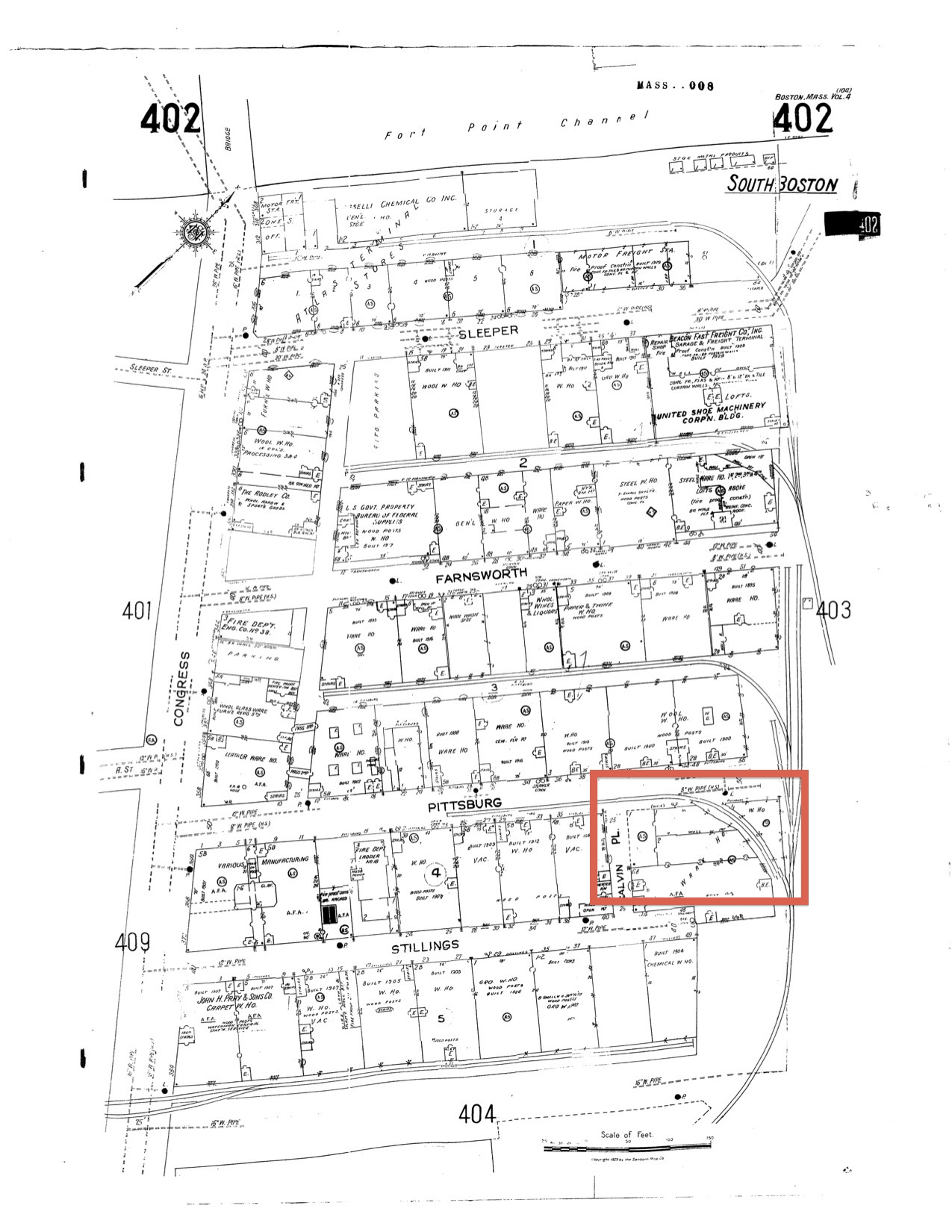

The medallions aren’t the only evidence of the Wharf Company. The buildings that they are on are themselves artifacts of the company. This is particularly significant because as a result of the Wharf Company building a large number of the buildings, the architectural style of Fort Point is nearly uniform, disrupted only by the most recent buildings. The Boston Wharf Company no longer has an active presence in Fort Point. However, its influence will never be forgotten. Between the buildings, medallions, and Boston Wharf Street, the area is rife with remnants of the original developer of the area. While the buildings of Fort Point were largely built by the Boston Wharf Company, many have been renovated and fixed up. In some places, new buildings were built or are being built. This wave of renovation and construction has made the buildings artifacts in a second manner. Their original form is the result of the style and their intended use at the time of their construction. Styles and uses have changed since then. As a result, the buildings have changed. What stand today are not the products of either individual time period but rather the products of both time periods. Because an artifact is defined as anything man made, nearly every thing on a site can qualify as an artifact. However, that does not mean that every thing on site is useful as an artifact. Some of these things are more useful as a trace, as it is not their existence today that is important as much as what they signal about what was once important or what is no longer needed. A prime example of this is the shape of the façade of the omgeo building on the Seaport Boulevard side of Thompson Place. As can be seen in the picture, the building has a curved face. Such a floor plan cuts down on the amount of usable floor space, so it would not make sense to build a structure like that unless it was necessary. In fact, it was necessary, because of the rail lines that ran down the side streets off Congress Street. These rail lines serviced the warehouses that lined the street of Fort Point. As can be seen in the 1899 map below, the rail lines went in before the building took shape. Before 1923, the building was rebuilt, with a curved face that hugs the train tracks. Today, from an architectural standpoint, it is insignificant that the building is curved. But historically, it’s an indicator of a technological innovation that ensured Fort Point and the nation’s economic health for a long time. Sam Bass Warner Jr. reinforces this notion.

“The same money that financed the building of wharves and ships also funded the building of modern textile mills at river sites beyond Boston. These regional factories with their need for large-scale supply of coal, cotton, wool, and leather remade Boston into a nest of portside warehouses and rail yards, remnants of which survive behind South Station along lower Summer Street” (Warner Jr., 7)The rail lines allowed for rapid and cheap transit of wool to the textile mills located farther inland, playing a key role in the development of the region. This building is a monument to the formative power of the railroad.

Location of the omgeo building is marked with red rectangle (Boston. Map. 1899. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1895-1900 vol. 4, 1899, Sheet 2". Digital Sanborn Maps. http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000008.htm?CCSI=254n.)

Location of the omgeo building is marked with red rectangle (Boston. Map. 1899. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1895-1900 vol. 4, 1899, Sheet 2". Digital Sanborn Maps. http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000008.htm?CCSI=254n.)

Location of the omgeo building is marked with red rectangle (Boston. Map. 1950. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1929-Feb. 1951 vol. 4, 1923-Apr. 1950, Sheet 402a". Digital Sanborn Maps. http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000035.htm?CCSI=254n.)

Location of the omgeo building is marked with red rectangle (Boston. Map. 1950. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1929-Feb. 1951 vol. 4, 1923-Apr. 1950, Sheet 402a". Digital Sanborn Maps. http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000035.htm?CCSI=254n.)

While the railroad might have significantly aided in the development of the region, it was unable to buoy the wool industry forever. Between 1950 and today, the wool industry disappeared from Fort Point. Without the economic activity associated with wool, Fort Point went experienced a drastic change in inhabitance and economic climate.

Graffiti on the backside of an old Boston Wharf Company building. Note the lack of fire escapes.

Graffiti on the backside of an old Boston Wharf Company building. Note the lack of fire escapes.

In the picture above, is the backside of a building on Congress Street, with the most apparent trace being the graffiti. In order to paint the graffiti, the artists must have stood on fire escapes. However, the fire escapes are no longer there. This brings up the question: what does the lack of fire escapes and presence of graffiti mean? The graffiti can help explain the fire escapes. It is difficult to spray paint the side of a building that is inhabited and in a high traffic area without being noticed and caught. Therefore, when these buildings were being used as wool warehouses, they would have been hard to paint successfully. Once the wool industry moved out, though, painting these buildings would have been relatively easy. In this way, the graffiti is a trace of the economic hardship of the area. This points to why the fire escapes were removed: the buildings were no longer being used. There is no reason to have fire escapes on a building that is abandoned. The steel fire escapes must have been sold for scrap once the building was boarded up and relegated to abandonment. This period of vandalism raises another question: why didn’t the rest of Fort Point fall to this fate? Unfortunately, this question cannot be answered definitely with the evidence at hand. However, there are two possible explanations as to why Fort Point is not currently covered in graffiti. The first is that after the wool industry moved out, other tenants moved in and kept the graffiti artists at bay. The other is that the buildings did fall into a state of disrepair but were fixed up when the wave of renewal swept through the area. As was said, neither explanation is necessarily correct. In this case, it is the question that is significant, not the answer, as it prompts a more thorough examination into the period between the departure of wool and the arrival of capital. Having looked at the artifacts and traces of the site, it is now time to shift the analysis to the layers and trends. Spirn defines a layer as “something which is spread out over a surface; connecting multiple artifacts, through which, a series of strata is made visible” ("Podcast: Artifacts, Traces, Layers, and Trends"). As opposed to a site that might have many layers or different strata in different places, Fort Point is rather simple in that it consists of only three layers, one of which is the land on which the buildings rest. Each layer coincides with a major formative period in the history of Fort Point and as such, the layers appear in clear chronological succession: fill, original development, redevelopment. Fort Point, has exhibited a remarkable uniformity at any one time. This is only just changing as the third layer develops. As with the artifacts, the first layer to look at is the filled land. Unlike with the artifacts, though, it is clear as to why the filled land is a layer. It is the surface upon which the rest of the area was built. The next layer is the streets and buildings original to the site. It might be possible to break this layer up into multiple layers, but it is not a worthwhile exercise, as the ultimate goal of this investigation is to understand the history of the site in order to better predict what lies in the site’s future. Additionally, the problem with the creation of more, smaller layers is that while the layers existed at one time, they are no longer visible. Therefore, we are left with one visible historic layer. It is important to note that this layer is homogeneous in its land usage: industrial. This is a crucial layer for a number of reasons. Visually, it is through this layer that people interact with the history of the site on a daily basis. If this layer had been demolished at some point, the unique “sense of place” that Dolores Hayden spoke of would have been lost forever (Hayden, 235). From a developmental stance, this layer is important because without it, the next layer would be unrecognizable. This third layer is essentially a contemporary outcropping emerging out of the second layer. When Fort Point was redeveloped, the district was not leveled. Instead, the old buildings were used as scaffolding for a new district. As a result, the third layer does not attempt to cover the second layer. The third layer builds upon the second layer and propagates out of it. Evidence of this is everywhere. On Congress Street, a copper and glass structure rises out of two original Boston Wharf Company buildings. Also on Congress Street, the Children’s Museum is a glass and metal frame growing horizontally out of a brick building. One of the few new buildings in Fort Point is located directly on the channel. It’s entirely glass, with a face that nearly extends down to the water. Finally, on A Street, an office building features a gray sheet metal entranceway. Fort Point’s third layer does not only extend up and out. It also extends down. The silver line runs underneath Fort Point, providing access to the district via public transport. This is also part of the redevelopment of the district: bringing people to the area.

Copper and glass addition to the top of the old brick buildings

Copper and glass addition to the top of the old brick buildings

Children's Museum with its metal addition

Children's Museum with its metal addition

Sheet metal entranceway

Sheet metal entranceway

New building on the Fort Point Channel

New building on the Fort Point Channel

For the first time, with the third layer, land usage begins to become diversified. No longer is every building dedicated to industrial uses. Beginning with the third layer, residential, business, institutional, and mixed lands uses creep into the area and gain a significant footing.

Boston Redevelopment Authority

Boston Redevelopment Authority

Perhaps this layer is a new type of layer. In the past, layers competed with each other. One layer would be removed or heavily modified to make way for a new layer of development. In this third layer, though, we see a layer that seeks to work with the existing layers rather than crowd them out. The result is a more integrated redevelopment, one that embraces the history of the site instead of burying it. This new type of layer points to an overall trend in Fort Point that is no more than ten years old. This is the trend of responsible redevelopment. As mentioned before, this redevelopment has taken place in a way so that new structures compliment the existing structures and pay homage to the character of the district. A fantastic example of this can be seen at the corner of Melcher Street and A Street with the Factory 63 Apartments. Its sign has fake rust spots, in an attempt to capture the vintage industrial feel. As mentioned before, the land uses are beginning to change, because of desirable apartments like these.

Rust isn’t the only vestige of the past that is being mimicked, though. The building medallions are also being used again. This is an attempt by the developers to tie the new development to the character of the old Fort Point integrate the new building into the existing character of the neighborhood.

Two BW Co. medallions. Medallion on the left is from 2001. Medallion on the right is from 1907.

Two BW Co. medallions. Medallion on the left is from 2001. Medallion on the right is from 1907.

For the sake of Fort Point, one must hope that this trend of responsible development has displaced the previous trend of abandonment. All indications point to the fact that the former has replaced the latter. However, I did find a playground that was recently completed but fenced off and empty. Such an image stands in direct contrast to the rest of the district, but recalls the image of the graffiti and the difficult period that Fort Point went through.

The question is raised: will Fort Point succeed? The combination of responsible development and a site with a rich history must lead one to believe that the district is in the middle of an upswing and that it will become as vibrant as it once was during the heyday of wool. Construction is still ongoing; the district is still being redeveloped, but slowly, the area is being reclaimed and reimagined.

There is more at stake here than just the future of Fort Point, however. Responsible development is also undergoing a referendum on its effectiveness. One must hope that the results are favorable for this new development style, as it doesn’t only encourage, but rather forces citizens to interact with the site’s history and “sense of place.”

Currently, “planners’ maps show no buried rivers, no flowing, just streets, lines of ownerships, and proposals for future use, as if past were not present, as if the city were merely a human construct not a living, changing landscape” (Language of Landscape, 11). Going further, though, planners’ maps show no history, no understanding of the forces that acted on the given parcel, be they social, economic, or environmental. While understandable, as such qualities are difficult to map, their absence has led to a belief that they are unimportant, which further reinforces the notion of the city as a “human construct.” As this semester long investigation of Fort Point has demonstrated, the “human construct” is a fallacy. The city is in fact a “living, changing landscape.” Gradually, as evidenced by the trend of new development in Fort Point, it seems that developers and planners are coming to the same realization. As inhabitants of the city, we must make sure that they do.

Works Cited

Boston. Map. 1899. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1895-1900 vol. 4, 1899, Sheet 2". Digital Sanborn Maps. http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000008.htm?CCSI=254n.

Boston. Map. 1950. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1929-Feb. 1951 vol. 4, 1923-Apr. 1950, Sheet 402a". Digital Sanborn Maps. http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000035.htm?CCSI=254n.

Boston Redevelopment Authority. "South Boston." Map. Boston Redevelopment Authority, n.d. Web. 5 Apr. 2013.