The changes of a specific location can be difficult to notice, and even harder to trace over time. Even when ever minor alteration of a site has been noted, the changes can seem random and impossible to explain, or so subtle that they do not matter. As Jackson noted, “it is difficult to make solid statements differentiating the values and lifestyles of various groups based largely upon residence.” (Jackson 11). With much deep analysis, correlations can be spotted between changes and well-known historical trends that may have affected a specific site. However, it is impossible to explain everything without observing patterns in the change and speculating the cause for such patterns. These patterns of change on my site in the North End and Greenway have provoked hypotheses for the causes of such change.

A good way to trace change over time is to view several maps of the same site from different decades and find the differences between each of them. The most significant changes I have found on my site are the surge and waning of industry, the disappearance of the wealthy that first settled the area, and the new physical features that were necessary each time a new type of transportation became popular. All of these changes affected my site and interacted in unique ways, each pattern feeding off the other and causing a new set of changes.

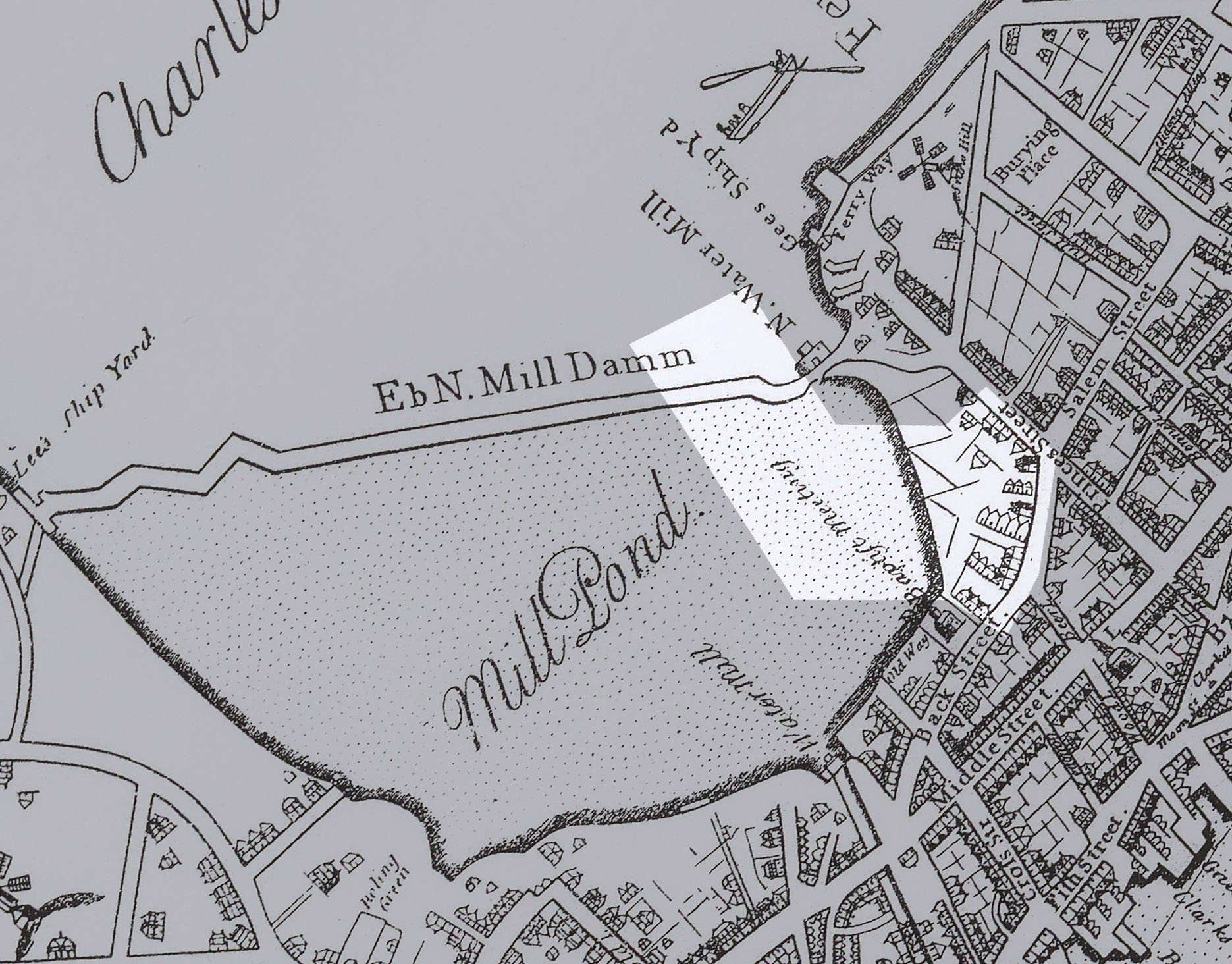

Figure 1: Bonner, John. The Town of Boston in New England. Map. 1722. Digital file. (click image to enlarge)

Figure 1: Bonner, John. The Town of Boston in New England. Map. 1722. Digital file. (click image to enlarge)

Until the early 1800s, most of my site was still water. Figure 1 shows a map of 1722 and the Mill Pond that covered a large area of northwestern Boston. Only the very easternmost blocks of my site were dry land, and they already had significant residential development while the rest of my site was still a pond.

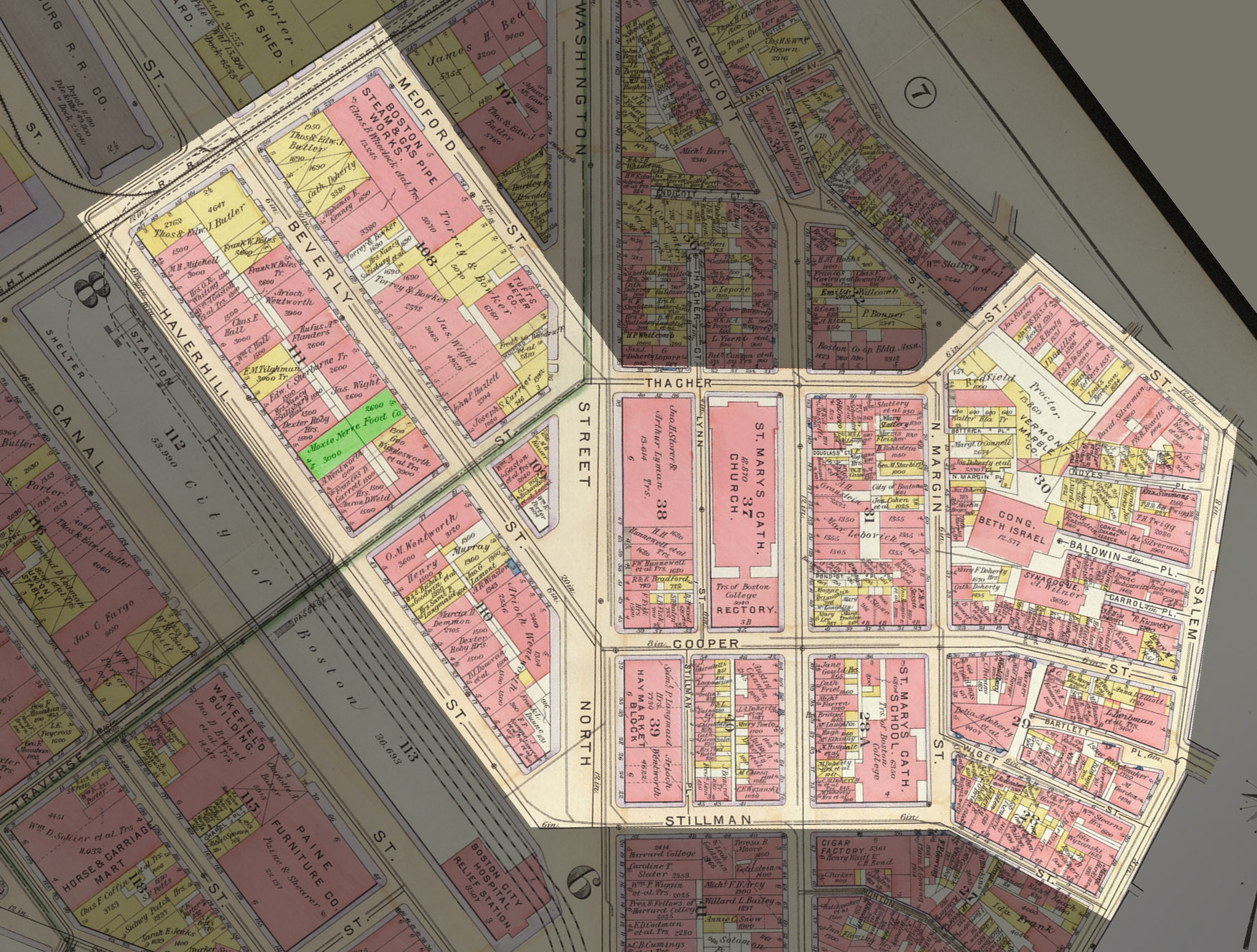

Figure 2: Sanborn, Daniel Alfred. Insurance Map of Boston. Map. 1867. Digital Sanborn Maps. Web. 15 May 2013. <http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000001.htm?CCSI=254n> (click image to enlarge)

Figure 2: Sanborn, Daniel Alfred. Insurance Map of Boston. Map. 1867. Digital Sanborn Maps. Web. 15 May 2013. <http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000001.htm?CCSI=254n> (click image to enlarge)

By 1867, my site had changed drastically. As can be seen in Figure 2, Mill Pond had been filled in and a lot of industrial development had taken root. The map shows many blacksmith, coppersmith, and other metalworking buildings, as well as a few marble working companies west of Charlestowne Street. East of Charlestowne Street, there are mainly single-family dwellings, except for St. Mary’s Catholic Church on Endicott Street and a school on Cooper Street. In general, Charlestowne Street seems to divide the site between industrial and residential neighborhoods, because it marks the edge of the Bulfinch Triangle, the part of Mill Pond that was gridded evenly together.

Figure 3: Bromley, G. W. Atlas of the City of Boston, Boston Proper, and Back Bay from Actual Surveys and Official Plans. Map. 1883. MIT Lib., Cambridge. Dome. Web. 15 May 2013. <http://dome.mit.edu/handle/1721.3/47999>. (click image to enlarge)

Figure 3: Bromley, G. W. Atlas of the City of Boston, Boston Proper, and Back Bay from Actual Surveys and Official Plans. Map. 1883. MIT Lib., Cambridge. Dome. Web. 15 May 2013. <http://dome.mit.edu/handle/1721.3/47999>. (click image to enlarge)

Figure 4: Sanborn, Daniel Alfred. Insurance Map of Boston. Map. 1885. Digital Sanborn Maps. Web. 15 May 2013. <http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000002.htm?CCSI=254n>. (click image to enlarge)

Figure 4: Sanborn, Daniel Alfred. Insurance Map of Boston. Map. 1885. Digital Sanborn Maps. Web. 15 May 2013. <http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000002.htm?CCSI=254n>. (click image to enlarge)

As the next two decades passed, the area continued to grow in industry. Figures 3 and 4, maps from 1883 and 1885, show a few names that own several large plots of land, including residential homes and industrial companies. It seems that the wealthiest families on my site were Wentworth, Cowdin, Torreys, and Bartlett, because they all owned multiple plots of land, both industrial and residential. The names of these families have been highlighted on the map in Figure 3. Another change that is evident in Figure 4 is the spread of industry across Charlestowne Street. There are two large factory buildings on the eastern side of Charlestowne Street that were not present before. There are also more marble companies than before, and a big rubber company taking up a whole block along Charlestowne. A few lumber and woodworking companies have also appeared. This seems a bit strange, but might be explained by the changing technologies and needs for certain types of industry.

Something else has appeared that might be relevant; just across Haverhill Road from my site, the Boston & Maine Passenger Railroad can be seen in Figure 4. In Figure 2, there was a freight rail station in the same location, so it can be assumed that this switch from freight to passenger train at this station would have some effect on the surrounding area. This passenger train may explain why the types of industry changed. Perhaps companies that needed a lot of heavy materials could no longer be successful there, and instead companies that needed lots of lower class workers showed up because it was convenient for workers to ride the train there for work. According to Jackson, “the result [of better transportation] was hailed as the inevitable outcome of the desirable segregation of commercial from residential areas and of the disadvantaged from the more comfortable.” (Jackson 20).

Another anomalous change can be seen on the eastern side of my site. St. Mary’s Church that was first seen in Figure 2 is again seen in Figures 3 and 4, but it is now much bigger, taking up an entire block. In addition, the Cooper Street School from Figure 2 is now renamed to St. Mary’s Catholic School. These changes indicate an increased following of the Catholic Church in the area. This can possibly be explained by an increase in Italian population during this time period (Nichols).

Figure 5: Sanborn, Daniel Alfred. Insurance Map of Boston. Map. 1885. Digital Sanborn Maps. Web. 15 May 2013. <http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000008.htm?CCSI=254n>. (click image to enlarge)

Figure 5: Sanborn, Daniel Alfred. Insurance Map of Boston. Map. 1885. Digital Sanborn Maps. Web. 15 May 2013. <http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000008.htm?CCSI=254n>. (click image to enlarge)

Towards the end of the century, the types of industry seemed to change even more. In the map of 1895 (Figure 5), there is no metalworking to be seen, and marble working and wood working industries dominate the area west of Charlestowne. A very large building labeled “Vermont Marble Co.” has also appeared on Thacher Street on the eastern side of my site. The changes that may have been started by the replacement of the freight line with the elevated passenger train appear to have continued.

There is also evidence that the resident population has changed. In all the prior maps, the Home for Little Wanderers can be seen just off of Margin Street at a strange angle. The Home for Little Wanderers was an orphanage that started a chain of orphanages and related organizations that still operates today in other locations (Home for Little Wanderers). In place of the orphanage, Figure 5 shows that the building has been turned into an Israel Synagogue. This would indicate an influx of a different culture, perhaps brought in by workers from the passenger rail line.

Figure 6: Bromley, G. W. Atlas of the City of Boston, Boston Proper, and Back Bay from Actual Surveys and Official Plans. Map. 1902. MIT Lib., Cambridge. Dome. Web. 15 May 2013. <http://dome.mit.edu/handle/1721.3/47999>. (click image to enlarge)

Figure 6: Bromley, G. W. Atlas of the City of Boston, Boston Proper, and Back Bay from Actual Surveys and Official Plans. Map. 1902. MIT Lib., Cambridge. Dome. Web. 15 May 2013. <http://dome.mit.edu/handle/1721.3/47999>. (click image to enlarge)

The 1902 Bromley map in Figure 6 shows different types of changes that were going on during that time. Many of the big names that were seen on the 1883 Bromley map are now gone, and their large industry companies have been replaced by much smaller companies. There are more, even smaller residential properties east of Washington Street. Presumably, as the wealthy left, they gradually sold their rental properties to their tenants. One new company that can be seen in Figure 5 is the Moxie Nerve Food Company, which we recognize today as the company that later produced the popular Moxie soda drink. While there are still many small industry buildings, including woodworking shops and factories, it seems like the amount of heavy industry has generally declined on my site.

Figure 7: Sanborn, Daniel Alfred. Insurance Map of Boston. Map. 1908. Digital Sanborn Maps. Web. 15 May 2013. <http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000019.htm?CCSI=254n>. (click image to enlarge)

Figure 7: Sanborn, Daniel Alfred. Insurance Map of Boston. Map. 1908. Digital Sanborn Maps. Web. 15 May 2013. <http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000019.htm?CCSI=254n>. (click image to enlarge)

Between the maps for 1895 (Figure 5) and 1908 (Figure 7), there are several new features on my site. In addition to the new synagogue where the Home for Little Wanderers orphanage had once been, there are a couple other new synagogues and several other traces of Jewish culture, as can be seen highlighted in yellow. The alleyway in between these buildings has also been renamed from Bartlett Pl. to Jerusalem Pl., indicating the growth of the Jewish population in this small area. It is interesting that this influx of culture has sprung up so quickly, but it could possibly be attributed to the new kinds of manufacturing that offer new jobs for lower-class workers.

A very subtle change on the maps (but perhaps the most important one) from the 1800s to the 1900s is that many of the buildings that are marked as dwellings in 1895 and before are now marked as flats in the 1908 map. This indicates that they are apartments rather than single-family homes, which points to an interesting change of residents. All of the important wealthy names from the 1800s are also gone or mostly gone now, and it seems that there has been an influx of lower-class residents. According to Jackson, the “privileged urban group had essentially three residential options in the latter three decades of the nineteenth century – to remain in a private dwelling within the city, to move to an elegant apartment house, or to relocate on the growing edges.” (Jackson 91). Since the apartments on my site were hardly elegant, the wealthy began to move away as it became difficult or unreasonable to keep their private dwellings. There are also a large number of tiny stores interspersed with the residences, which is how the North End has remained to this day.

The Vermont Marble Co. building, which first appeared in the 1895 map and is still present in the 1902 map, has now been split into various manufacturing buildings. This indicates a general decline in the large metal and marble industries of the area, which can also been seen in many of the other manufacturing buildings. Many buildings that were previously occupied by heavy industry companies have been converted into flats or smaller manufacturing companies and stores. Some buildings even have manufacturing on lower floors with flats in the upper levels. This may again be explained by the conversion of the train station into a subway station and passenger rail station, which would have prevented shipments of goods by freight train and increased residential capacity for the area by providing more transportation to other areas.

Figure 8: Sanborn, Daniel Alfred. Insurance Map of Boston. Map. 1929. Digital Sanborn Maps. Web. 15 May 2013. <http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000035.htm?CCSI=254n>. (click image to enlarge)

Figure 8: Sanborn, Daniel Alfred. Insurance Map of Boston. Map. 1929. Digital Sanborn Maps. Web. 15 May 2013. <http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000035.htm?CCSI=254n>. (click image to enlarge)

By 1929, my site looked much different than it had in the 1800s. My map of 1929, in Figure 8, shows that Charlestowne Street has been renamed to Washington Street. There is much less industry and many new loft apartments that have sprung up around Washington Street. There are almost no metalworking or marble companies to be seen; most of these buildings have been converted into shops or lighter industry such as furniture manufacturing. The large building which at the turn of the century housed the Vermont Marble Co. and later other manufacturing industries has been converted to a large loft apartment building. It appears to be housed in the same structure, but modified into a residential building. Other buildings that previously housed manufacturing companies have also been converted into lofts. These new loft apartments are highlighted in light blue on the map.

Another change related to the early 1900s can be seen in the addition of facilities for automobiles. In place of the synagogues and Jewish buildings that were seen in Figure 7, there are several private garages and parking lots along Margin Street. There are also two gas filling stations for automobiles on the corners of Traverse and Washington, and Beverly and Causeway. These changes, highlighted in purple in Figure 8, indicate the area’s continuing shift from industry to a more residential and commercial purpose, and highlight the newfound popularity of the personal automobile in the early 1900s.

Figure 9: Historic Boston - Aerial Photo. 15 Dec. 1949. Photograph. Massachusetts Dept. of Transportation. (click image to enlarge)

Figure 9: Historic Boston - Aerial Photo. 15 Dec. 1949. Photograph. Massachusetts Dept. of Transportation. (click image to enlarge)

Figure 10: "2003 Boston Aerial [BWSC]." Map. The Boston Atlas. 2003. Web. 15 May 2013. <http://www.mapjunction.com/bra/>. (click image to enlarge)

Figure 10: "2003 Boston Aerial [BWSC]." Map. The Boston Atlas. 2003. Web. 15 May 2013. <http://www.mapjunction.com/bra/>. (click image to enlarge)

In the 1950s, the elevated John F. Kennedy Expressway, also known as the Central Artery, was built through a large portion of my site. The construction of the artery destroyed many of the old industrial buildings. From Figure 10, an aerial view of the area from 2003, one can see how the construction of the artery has separated the neighborhoods to the east and west of my site. Many of the buildings near the artery are older and more run-down, and some have apparently been abandoned due to the artery’s negative effects on desirability and land value in the area (Mirabella). The eastern side of the area, however, remains as stores and flats in roughly the same form as they were in the early 1900s. Notably, St. Mary’s Catholic Church still exists in its original location, but in a new building that it shares with apartments.

Figure 11: "2005 Mass Color Ortho." Map. The Boston Atlas. 2005. Web. 15 May 2013. <http://www.mapjunction.com/bra/>. (click image to enlarge)

Figure 11: "2005 Mass Color Ortho." Map. The Boston Atlas. 2005. Web. 15 May 2013. <http://www.mapjunction.com/bra/>. (click image to enlarge)

The Artery was moved underground sometime in the early 2000s. Figure 11 shows an aerial view of my site in 2005, which appears to be immediately after the last of the aboveground artery was demolished. New construction can already be seen immediately surrounding the area where the artery was, and it appears that the area will be kept clear instead of being redeveloped.

Figure 12: "Boston, MA." Map. Google Maps. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 May 2013. <https://maps.google.com/?ll=42.364838,-71.057832&spn=0.005065,0.008658&t=h&z=17>. (click image to enlarge)

Figure 12: "Boston, MA." Map. Google Maps. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 May 2013. <https://maps.google.com/?ll=42.364838,-71.057832&spn=0.005065,0.008658&t=h&z=17>. (click image to enlarge)

In Figure 12, a current aerial view of the area, one can see the finished Rose Kennedy Greenway. It looks very open and welcoming with its many accommodations for pedestrians, including the nearby MBTA stops, Haymarket and North Station. Upon visiting the site, once can see that there is still new construction immediately adjacent to the Greenway on both sides, and several newly finished buildings with space for rent. It appears that the area is becoming a primarily new and higher-class commercial area today. The future of the site is very uncertain; the trend may spread through the North End to further commercialize it for upscale visitors, or it is possible that the small neighborhood culture will be preserved.

All of these maps together paint an interesting picture of a site that has changed greatly over the last two centuries: from a mill pond, to an industrial region with wealthy residents, then to a lower-class residential area with strong cultural populations and shops and services intermingled with apartments in old, 18th century buildings. Although the changes from one map to the next seem quite subtle, they form important patterns that, when viewed together, reveal major trends in the site’s uses and its residents. The new construction near the Greenway today, the decrease in property value around the artery in the late 1900s, the decrease in industry and departure of wealthy owners in the early 1900s, the industry surge and influx of the lower class in the late 1800s, and the original wealthy landowners are all trends that are related in complex ways. These trends have shaped the history of the site over the last two hundred years. The depth of correlation between these seemingly subtle or random changes in such a small site is truly amazing, and one can only imagine how the site might grow in the future.

Works Cited

Home for Little Wanderers. History. 14 May 2013 <http://www.thehome.org/site/PageServer?pagename=about_history>.

Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Mirabella, John. The North End: From Isolation to Transformation, the Construction and Deconstruction of the Central Artery. 23 April 2013 <http://johnmirabella.wordpress.com/the-north-end-from-isolation-to-transformation-the-construction-and-deconstruction-of-the-central-artery/>.

Nichols, Guild. Part 5: Boston's Little Italy. 14 May 2013. <http://www.northendboston.com/2010/09/north-end-history-volume-5/>.