From the outside, Boston seems like an antiquated city with landscapes ranging from narrow, cobbled streets lined with pedestrians and tiny wooden and brick shops, to multi-lane highways and clumps of shiny skyscrapers swirling with cars and trains. But what may not be so obvious is the complex relationship Boston has with the natural environment. Boston was created and shaped by the sea and waterways. It evolved as a harbor city that thrived so well that it needed to fill in the ocean to have room to grow. It is now a very busy place that seems as if it were created to meet the needs of the thousands of people that swarm around it every day, but in fact, it was not. People chose how to change Boston to suit their needs and desires, but their decisions were affected by the geography and environment and in turn had a profound effect on both of these things.

The central North End region of Boston was on the original higher central ground. Although it was not one of the very earliest areas to be civilized, it had already come to life by the late 1700s. Because that area was on the original unfilled land, it became densely developed by the time more filled land was available. My site was on the edge of the Mill Pond and the sheltered side of the harbor, so it had easy access to energy from the dam as well as sea traffic, which made it a very useful place to put more industrial properties, as opposed to the central part of the North End, which was (and still is) primarily small shops and residences.

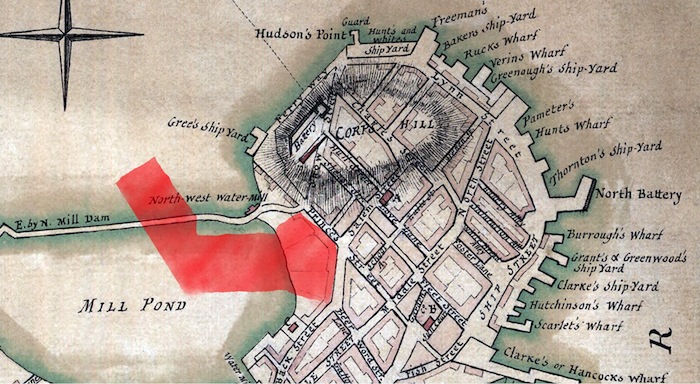

Photo from Library of

Congress; created by Sir Thomas Hyde Page in 1777. The location of my site is

indicated in red.

Photo from Library of

Congress; created by Sir Thomas Hyde Page in 1777. The location of my site is

indicated in red.

However, my site was not all on the high ground. A large portion of it, including what is now the Greenway and I-93, is filled land. In the 1700s, there was a Mill Pond that covers the area now known as Bulfinch Triangle that provided resources for residents. The location of the dam now forms Causeway Street, which crosses the Greenway in the northern tail of my site. Mill Pond was filled in when residents wanted more room to expand the city. Many of these early expansions were largely owned by one person or a small group of people, but the land division that resulted from Mill Pond seemed to be more generally communal. There are a lot of smaller properties with old buildings that seem to have been there almost since the land was filled in, which would imply that many people got to claim a share rather than just the wealthy company that filled the land in the first place.

There is a noticeable change about two thirds of the way across my site that is probably due to the former shoreline. There is a break in the grid accompanied with a change in building type. To the east of the break, there are smaller, older looking buildings. To the west, there are more large apartment buildings. While the materials, style, and height of the buildings are very similar, the land usage is different in that on the east side, the properties are very small whereas on the west side they tend to be larger, and become very large and new close to the Greenway. This is probably partially due to the prior presence of the Central Artery, but also to the fact that the western portion is filled land.

Two breaks are evident in

this photograph. The foremost one is probably due to the presence of the

highway, while the second one seems to follow the old shoreline and may be due

to the fact that the area west of it is filled land.

Two breaks are evident in

this photograph. The foremost one is probably due to the presence of the

highway, while the second one seems to follow the old shoreline and may be due

to the fact that the area west of it is filled land.

After Mill Pond and most of my site was filled in around 1807, the area in the west of my site had plenty of new growth. A bridge had opened from Boston to Charlestown (somewhat near to the location of the current I-93 bridge) in 1786 to replace the prior ferry service. Because this point initially marked the shortest distance between the island of Boston and the mainland, it was the precedent for the general location of a traffic route. This route had many bridges built on it throughout the history of Boston, including footbridges, train bridges, and automobile bridges, and is still very important today in crossing the Charles and directing traffic into northern Boston.

Because the North End region is so crowded and was heavily developed so early, there is not a lot of open space or room for plants to grow. Other than on the Greenway, there are only a few sad looking trees planted in tiny square plots along the narrow streets. Instead, people put flowerpots on porches and windowsills and keep plants inside windows where they can thrive without being buried by plowed snow and trampled by foot traffic.

A

tree and two flowerpots share a tiny square in the sidewalk on Thacher Street.

A

tree and two flowerpots share a tiny square in the sidewalk on Thacher Street.

In the center of the easternmost block of my site, there are a few alleys that lead into a little deserted space behind the backs of buildings due to a break in the street grid. This little deserted space has a few scraggly plants growing at the edge of parking lots and some ivy climbing up fences and walls. It is secluded enough to offer some protection for the plants where they will not be destroyed by traffic or removed due to being an eyesore. But even there, they struggle to survive amongst the difficult conditions. As Spirn noted, “Unfortunately, the city’s most valued public spaces are among the most stressful [for plants]; streets, plazas, and parks can aggravate the worst problems of the urban environment.” (p. 175). People obviously like having plants around given that they hang pots and plant flowers in windows, but the crowded city environment just is not conducive to plant growth.

This poor plant survived

for a season in a patch of soil where some bricks had been removed.

This poor plant survived

for a season in a patch of soil where some bricks had been removed.

The Rose Kennedy Greenway is an example of Boston’s attempt to stop the inevitable urban war against greenery that accelerated in the 1900s. It can be easy to say that cutting down one tree makes a negligible difference, but when everyone in the city cuts down the tree on their property to make room for more buildings, it makes a significant difference. In my entire site, I only saw one tree that looked as if it were much more than ten years old. It was at the side of a private driveway, leaning away from the building, stretching upwards from the tiny patch of soil that was its sole connection to all the nutrients it received.

The

last old tree standing in my site stands from a humble patch of dirt.

The

last old tree standing in my site stands from a humble patch of dirt.

The Greenway may not look like much, but it was a huge step for Boston when it opened in 2008 in terms of becoming healthier and more natural. When the Big Dig took place and I-93 moved underground in 1991, the people of Boston chose to replace it with something nice instead of another stuffy highway. The Greenway is not only an aesthetic bonus and a social gathering place; it is a valuable resource of plant life that helps clean the air and restore more natural wind and rain patterns to the surrounding area. If the Greenway is maintained in the spirit with which it was created, it will continue to be a valuable resource to Boston where tall, leafy trees can thrive without having to break through sidewalks and fences and grass can grow without being trampled or covered with pavement.

As it is, however, the Greenway might seem like a waste of valuable space. It is just a strip of green in between other streets and concrete spaces, and serves as a good place for plow trucks to dump their snow piles in the winter. It looks like a giant wound running through the heart of north Boston, like it had literally lost its Central Artery. The giant open space between the river and the tall, expansive buildings on each side makes a visitor feel quite diminutive. The elevated highway that was erected in 1959 was a symbol of modernism and societal growth, so the Greenway needed to feel at least as grand as the concrete monstrosity that it replaced. The reason the public was open to this new type of change, a development for environmental and aesthetic purposes rather than convenience and necessity, was because with new developments in transportation, they could commute from downtown Boston to the surrounding area easily and quickly without feeling the need to cram everything within walking distance of the city center.

The Greenway also helped the environment of northern Boston because of the water patterns there. Much of the groundwater runs through drainage systems straight into the Charles River. With the Greenway, a large amount of the dirty water from the heavily traveled grounds of northern Boston that would normally run across pavement and into the river is instead absorbed into the ground through the large unpaved areas and can seep into the water table and surrounding bodies of water more naturally. The Charles, often used for recreation and as an aesthetic piece of Boston history, is very polluted because of the previous drainage systems that were implemented by Boston before better technologies were available.

The seemingly useless open

air where the Greenway is helps the city to feel more natural and healthy

instead of dirty and overcrowded.

The seemingly useless open

air where the Greenway is helps the city to feel more natural and healthy

instead of dirty and overcrowded.

Microclimate is an important part of what allows plants to grow or what causes them to suffer. The urban environment is inherently full of terrible growing conditions. Tall buildings shadow plant’s hungry leaves, rainwater drainage systems steal the water from their roots, and all the human traffic and movement hurts the plants. Plants cannot just find a new place to live or move out of the way like humans can. Instead, they must try to adapt by growing taller, leaning away from the buildings, sinking their roots deeper, or even bursting fences and sidewalks so that they have room to grow. Humans do not always take kindly to plants trying to survive by destroying their property, and often would rather cut down a tree than have to build a wall around it.

The north-facing tree on

the right has had to adapt by leaning into the street to gather the light that

comes over the tall building beside it.

The north-facing tree on

the right has had to adapt by leaning into the street to gather the light that

comes over the tall building beside it.

Many people in Boston have tried to grow plants for aesthetic purposes by hanging pots or planting a few flowers or bushes. Flowerpots are used as decorations in many shop windows just as Christmas lights or toy figures might be. Residents create their own microclimates that are suitable for plants since the plants could almost certainly not survive on their own. As I walked through my site, I saw everything from a spiral bonsai in a pot to some tropical plants hanging under heat lamps in front of a restaurant. The trees planted by the city appeared very unhappy in comparison to these pampered “pet” plants, albeit much more natural. The general mindset of the city seems to be that humans should change the landscape to satisfy their whims.

These plants appear so

unnatural that they cannot rightfully be called part of the natural

environment, but rather someone’s decorative objects.

These plants appear so

unnatural that they cannot rightfully be called part of the natural

environment, but rather someone’s decorative objects.

Trees and bushes are so sparse that they look somewhat out of place, as if they would fit in better as metal light poles instead. It seems strange to me (since I grew up in a small town) how a city can exist so long that it lacks plants that grow naturally and people feel the need to reintroduce them like animals into a zoo. Perhaps it will not feel quite so strange in summer when the few trees and flowers are in bloom and the grass is green, or perhaps the plants have adapted well and are as satisfied with their odd concrete-bound lives as seals doing tricks in a swimming pool.

These bushes have had a

special microclimate created specifically for their growth, with special

fertilized soil, heat coming out the vents behind them, and even caution tape

to discourage passerby from trampling them.

These bushes have had a

special microclimate created specifically for their growth, with special

fertilized soil, heat coming out the vents behind them, and even caution tape

to discourage passerby from trampling them.

Overall, the relationship my site has with natural processes is very unique. It was initially shaped by the sea, but then the people chose to fight back and shape the sea. It was once lush with green hills and trees like much of New England, but then the people chose to cut down the trees and erect buildings instead. It was originally developed around a bridge, and since then, the uses of that bridge have changed the area drastically. Boston decided to smash buildings and trees to create a giant thoroughfare, but then removed it in favor of trees and open space. The ebb and flow of environment and land usage is what keeps Boston a living, breathing city that is fed by its inhabitants and in turn feeds their needs.

Bibliography

Spirn, Anne Whiston. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design. New York: Basic, 1984. Print.

Page, Thomas Hyde, Sir. A Plan of the Town of Boston with the Intrenchments... 1777. Library of Congress. Web. 1 Mar. 2013. <http://www.loc.gov/resource/g3764b.ct000250/>.

All other photos taken by Michelle D. Barchak on Feb. 28, 2013.