I. Then and Now

Andrew Square had an abundance of natural features before manmade features transformed the site. Before the 20th century, Andrew Square was sandwiched between the South Bay and Dorchester. You can imagine the boisterous choirs of seabirds and steady currents of wind off the bays that softened the rest of the environment. Boston city government and Andrew Square residents were the major driving forces for natural processes that began post-19th century. Issues created by poor water drainage, litter, and more plague the site. The natural processes present at Andrew Square tell a tale of city and personal expansion.

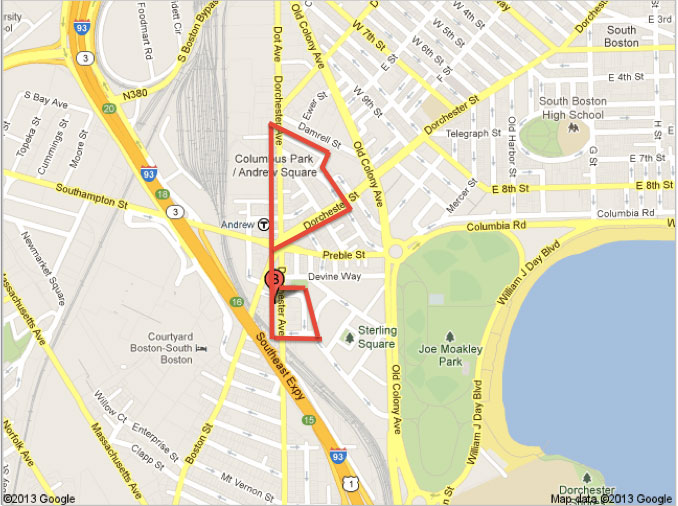

Figure 1. Andrew Square in 1890 (left), 1930 (right). Adapted from the Boston Redevelopment Authority.

II. Shores No More

Figure 2. Dexter Street.

There is still evidence of Andrew Square’s shoreline past: a faint breeze, a small group of seabirds, and old homes. When you arrive on site the temperature is noticeably colder than it is Downtown. During my most recent visit, the winds had picked up to 10 mph and the air was cold and wet. The calls of two seagulls swooping above the border of the natural and filled land were eerily symbolic (Figure 3). The land beneath Dexter Street is present on maps dating back to the 1700s. Much of the surrounding land was created at the turn of the 19th century.

A row of two story houses lines one side of Dexter Street. All the homes in Andrew Square are made of brick. On Dexter, most now have vinyl siding, and a smaller few, wood siding, for additional insulation. While the sea breezes today are not nearly as strong, there is still enough moisture that vinyl is necessary to prevent rapid deterioration. During my visit, a pair of seabirds was resting on one of the brick houses. That was the only bird sighting anywhere on my site I had \ during my three visits. In The Granite Garden, Spirn describes seagulls as more adaptable scavengers, which would explain why birds common to the suburbs, such as robins, are not present (Spirn).

When you turn north towards the Financial District, there is a vast no-man’s-lands. Litter lays next to tan weeds that are formidable enough to grow in the rocky soil. The filled land that was not purposed for transportation lines or residences became ugly stretches of wasteland that detract from the neighborhood. Poor city planning transformed part of one of the last bays in Boston into an eyesore.

Figure 3. Seabirds resting by Dexter Street.

III. Wasted Space

The unused land that borders the small residential neighborhood on Dexter Street and the industrial park at Alger Street is an enigma. Besides being criminally unattractive, the mysterious empty plot is a hazardous dumping ground. The area is 450 sq. ft. and classified as surface parking by the Boston Redevelopment Authority; surface parking is the default classification for non-residential, commercial, or industrial land use (Boston Redevelopment Authority). Figure 4 shows a collection of trash next to the gate: an old tire, empty bottles, and children’s bedding. Whatever toxins that are released when the garbage decomposes will eventually reach the streets, the city sewer system, and finally, pollute the Harbor, where most waste is dumped. I researched explanations for why this particular plot was abandoned.

Figure 4. Unused filled land to the right of Dorchester Avenue.

Hazardous waste found during the construction of the adjacent Andrew Square Station may be an indicator of soil problems on the filled land. Prior to breaking ground, the ABB Environmental Services, Inc. tested the soil in the land bordered by the railroad, Ellery Street, and Southampton Street. The station site was formerly occupied by small manufacturing companies, auto body and heating businesses (ABB-ES). They found widespread lead and total petroleum hydrocarbon contamination. Much of the contaminated soil was removed offsite because it was a health hazard to the construction workers. The Granite Garden quotes a 1977 study that found traces of lead in two-thirds of gardens tested (Spirn). My research of historical maps did not show that the land was ever used, but its proximity to former or current industrial sites to the north and south hint that there may be soil contamination issues. The area is contained by a large fence, but peeking through, I saw no evidence of activity on the site or any other reason to fence it in. If soil is poisoned, the area may be fenced to prevent exposure to toxic substances.

The signs of life on the otherwise naked and possibly poisoned land are an achievement. There are a number of opportunistic plants and some trees. Most common are an unknown species of two feet tall weeds that proved formidable in the rocky soil. I saw the same plant growing in small cracks in the concrete in neighboring residential neighborhoods and on the sidewalks along major roads. The left image in Figure 5 shows some of the other vegetation in the empty lot: bright green and orange mosses and a red barked plant. Although the land has scattered concrete stretches, it could be a beautiful large green space for the residents. A large natural environment would enhance the aesthetics of the neighborhood and relieve the environmental threat posed by an unmonitored dumping ground.

Figure 5. Vegetation in the empty lot along Dorchester Avenue.

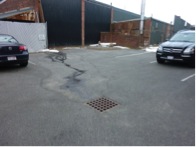

IV. Down the Drain

Water drainage is a rampant issue on the residential and public land in Andrew Square. The site’s “characteristic urban water regime,” as termed in The Granite Garden, is influenced by its flat topography and inadequate street and residential drainage systems for excess water and runoff (Spirn). A map from 1903 shows how flat the land is in the immediate area (Figure 6). Throughout the site, there are signs of water damage to the asphalt on driveways and roads from resting surface water.

The need for parking has an unexpected link to the Square’s drainage woes. Developers construct parking lots as an added bonus to the house and to solve a street parking crisis in the neighborhoods. Middle Street neighborhood has some car lots, while the Mary Ellen McCormack Housing Project only consists of street parking. While the McCormack Housing Project was built during the 1930’s and planned to have abundant trees and green space, the Middle Street neighborhood is three decades older. Homeowners and developers in the Middle Street neighborhood contemplate between more green space or more parking, and the individual decisions have unique environmental consequences.

Figure 6. Flat topography indicated on 1903 map. Adapted from MyTypo.

Natural processes provide clues of how the Middle Street neighborhood developed. Most of the houses in the neighborhood were constructed between 1895 and 1905 (Zillow). All are brick, as noted in Section II, to account for their proximity to water. The lots are narrow and have limited outdoor space. The need for parking is a modern problem. When the neighborhood was developed at the turn of the 19th century, cars were not invented. During the mid-century, families almost exclusively had one car that could be accommodated by street parking. Today, the median price to buy a home in the Middle Street neighborhood is $450,000 so I would hypothesize that many of these families have two cars for two working professionals (Zillow). A desire for green space must compete with this strong need for parking. The two residences pictured in Figures 7 and 8 demonstrate two ways property owners address the tradeoff, and how their decision affects the surrounding environment.

Figure 7. Carport without drainage system (left). Corner of mud where the runoff accumulates (right).

Figure 8. Small garden collects runoff from the roof (left). Water drain in the center of the carport (right).

In the development in Figure 7, the space between homes is filled with asphalt. In Figure 8, the homes are surrounded with gardens. On the left, there is no central drain. Towards the back of the property the ground slopes into one corner. The corner is bordered by a small garden with trees but the ground directly next the asphalt is completely muddy from the excess water that collects. The tree looks like an import by a recently property owner, but has enough soil and certainly enough water to steadily grow. The discolored asphalt is a sign of water damage. The choice to provide a wider space for cars to pass has resulted in improper drainage and shortened the life span of the asphalt. The gardens in the development in Figure 8 absorb runoff from the roof. Walking further into the property, the car park is purposefully sloped to direct excess water into a grated drain. While the shininess of the asphalt indicates that it was recently laid, I predict it will deteriorate less quickly than the asphalt in the neighboring development. The multiple drainage mechanisms add green space and better preserve the asphalt. Drainage in public areas requires a separate analysis because different factors are at play.

Figure 9. Puddle of water in parking lane on Dorchester Avenue.

The combination of natural land slope and frequent traffic affect how water drains on the street. On Dorchester Street, a majority of the water collects on the right side of the street. Most cars park on this side; it is the traffic coming into Andrew Square from the Financial District. There are indents in the areas closest to the curb from the repeated stress of the weight of cars. The road declines from the left side to the right side, increasing the amount of water that collects there. The puddles and holes interrupt the flow of water to the large drains located at street corners and allow trash and other inorganic materials to collect in them. Surface water has a similarly negative affect on this asphalt as it did on the improperly set up parking lot.

V. Found on the Ground

Each land use zone: residential, commercial, and industrial, contributes unique ground pollutants. Ground pollutants negatively affect the site’s immediate area because many sewage pipes drain into Old Harbor. The examination of an empty lot in Section III noted how the trash dumped there would release toxins into the ground as it decomposed. Andrew Square has an acute pollution problem. It was even noted in 2006 redevelopment plans created by the Boston Redevelopment Authority. The committee executing the Dorchester Avenue Improvement Study noted that there was an immediate need for more garbage receptacles in the area (CITE). The accumulation of garbage from the residents, public transportation riders who exit in the area, and industrial businesses is a giant mess.

Figure 10. Litter and plant life in the industrial park on Alger Street.

The Mary Ellen McCormack Project has rampant littering violators who are jeopardizing the cleanliness of the harbor and the nearby soil. I did not notice the trash problem during my first two visits because snow was still piled high on all the streets. During my most recent visit, I was shocked by the amount of trash. The most egregious violation of litter laws was a broken lawn chair left carelessly on the sidewalk (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Trash on the sidewalk on O’Connor Way.

The examination of water drainage in Section IV introduced how litter collects on the sides of Dorchester Street and Dorchester Avenue. The site has decent foot traffic from the total of five bus routes that run along both streets. I most frequently observed bottles, wrappers, and pieces of Styrofoam. The area has multiple convenience stores and small eateries. Their patrons may be contributing to much of the litter. After reading “The Costs of Waste” in The Granite Garden, I made sure to record any presence of waste management and recycling solutions on my site (Spirn). I did not see any recycling receptacle, except in the T station. The waste near the commercial sites damages the environment but is also a lost opportunity to recycle. The Dorchester Avenue Improvement Study does not mention a need for recycling bins, but I think that should also be included in the redevelopment plans.

VI. Conclusion

The natural processes present at Andrew Square strongly influence one’s perception of the site. While the site is zoned for some industrial land use, the residential and commercial land is still largely devoid of trees. Those that do grow have to screech through concrete. Roads are being rapidly worn by sitting water because the main roads and neighborhoods all existed before the car and were not constructed accordingly. The filled land is not only an eyesore but also a hazard to the Harbor as pollutants flow from the piles of trash. As the city expanded and residents were permitted increased mobility, the natural features on site suffered.

Works cited:

Boston Edison Company. “Final Construction Report: Andrew Square Substation (Station 106).” April 2005.

Boston Redevelopment Authority. “South Boston Dorchester Improvement Study Community Meeting.” Power Point. 27 Feb 2007.

Spirn, Anne. “The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design.” Basic Books. 1985.

Zillow. “7 Dexter St, Boston, MA 02127”. Web. 12 May 2013.

Zillow. “50 Middle St, Boston, MA 02127”. Web. 15 May 2013.

Appendix: