Andrew Square’s evolution through time was most influenced by its position on the border of Boston and Dorchester, proximity to Fort Point, and near adjunction to the Atlantic. The sites key features include railway and road transportation, a federal housing project, and until recently, a plethora of cheap flats and tenements. The sites changes were largely tracked using Sanborn Maps from 1889, 1899, 1923, 1950, and 1981 (see Appendix). In my initial site evaluation, I described Andrew Square as an area in flux, moving from its industrial roots to a middle class enclave. The maps have provided a different narrative: a working class neighborhood frequently subject to the will of the central government that will likely remain unchanged for several decades.

Transportation

Railroads and transportation lines proliferated on the site during its history in response to the growing need for transportation from Boston’s southern suburbs to the city center. Since Andrew Square is at the tip of one of two paths to Boston from southern towns, it was primed to host transportation lines. The longest existing road on site is Dorchester Avenue whose origins predate the 19th century. The parallel running Old Colony Line was created during the mid-19th century. In the early 20th century, an underground subway was constructed that came from the financial district and continued into Southern Dorchester. Then, during the 1950s the Southeast Expressway was erected. The transportation lines were erected extremely close to residential properties, and in one case, replaced properties. Andrew Square's low status as a working class neighborhood gave it little clout to shape or protest construction. The lasting implication of having numerous transportation lines within a neighborhood is deterring high-income-targeted development projects.

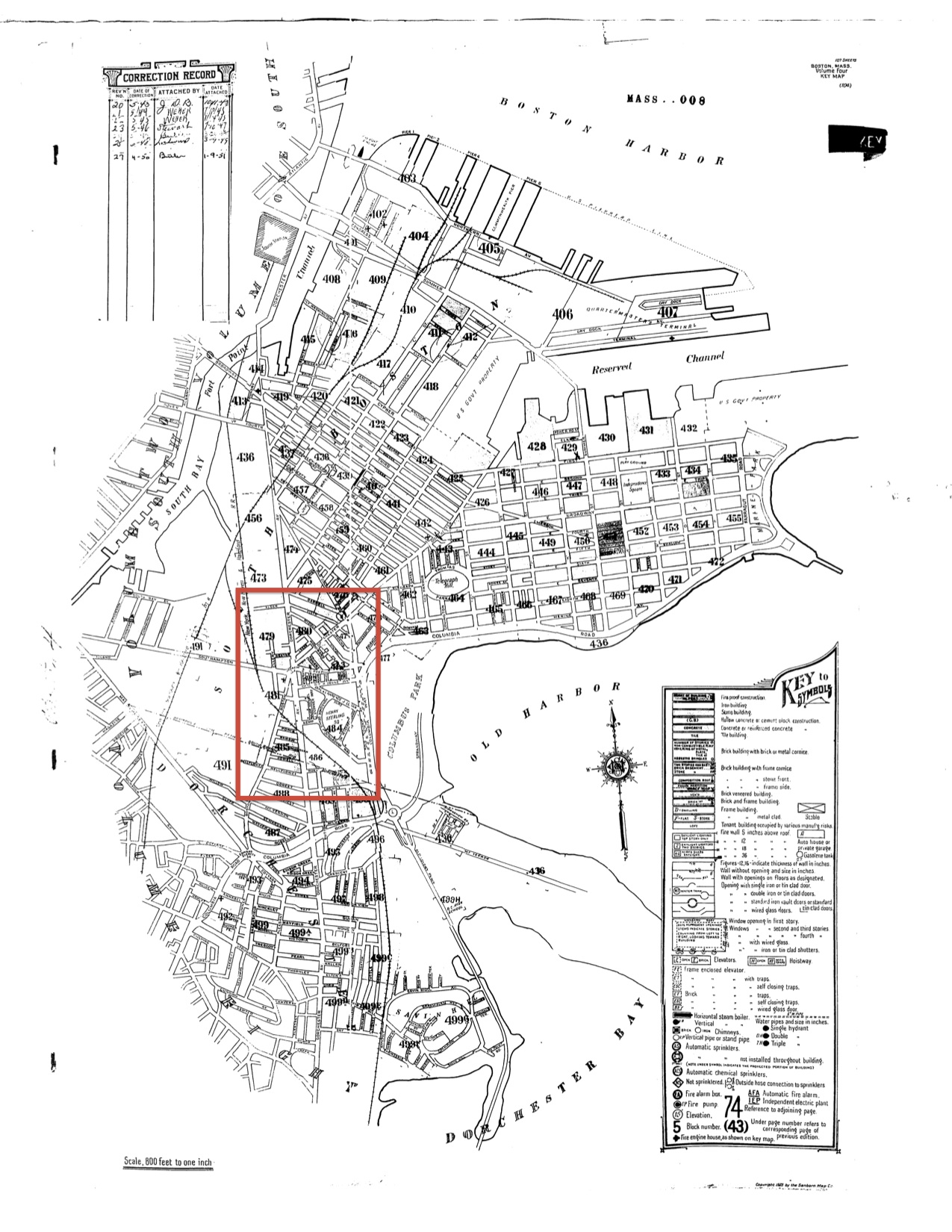

Figure 1. Map annotated with Dorchester Avenue, Old Colony Railroad, Dorchester Tunnel, and Southeast Expressway. (Google Maps)

Dorchester Avenue was a critical transportation path into Boston before the advent of railroads. The road was originally a cow path to pasturelands in Dorchester. In the early 19th century a charter converted it to a turnpike for carriages (Sammarco 7). It appears prominently on regional maps from that time period as a key route into Boston. Its use as a toll road was likely not profitable because it renamed Dorchester Avenue instead of Dorchester Turnpike on maps after the mid-19th century. The return of the road as a public entity was in tandem with the creation of railroads nearby and on Andrew Square. The parallel-running Old Colony line grew in prominence because it could more efficiently transport industrial goods and the well to-do (Jackson 91).

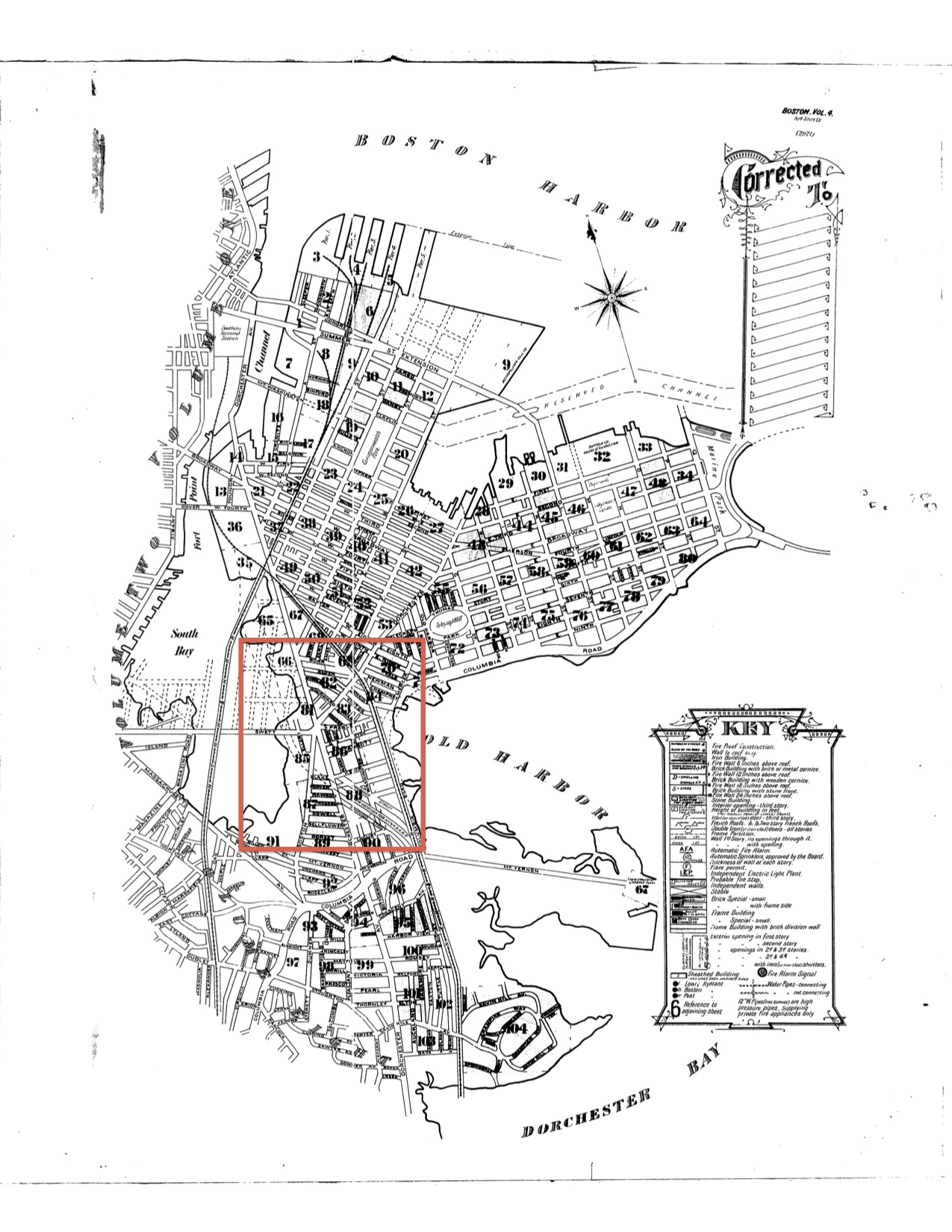

The timing of the creation of the Old Colony Line corresponded with a national explosion of railroad building during the mid-19th century. Railroads were sprouting along the North East Coast to connect major hubs and outlying towns to their city centers (Jackson 91). The Old Colony Line was created during the 1850s and ran parallel to Dorchester Avenue directly along the Atlantic Ocean. It connected Cape Cod, and towns in between, to Boston. Sometime near the turn of the century, part of the railway is redirected westward, beginning at Columbia Road. A comparison of the 1899 map to the 1923 map shows that within that time period, a portion of Old Harbor was filled (Figure 2). The filled land is thus labeled Columbus Park. Most likely, fill construction interrupted the railway and the pathway could either be redirected or cease operations until the fill was complete. While vast amounts of construction happened on site between the 1850s and early 1900s to the benefit of suburban commuters, there were fewer benefits for the residents of Andrew Square.

Figure 2. Path of Old Colony Railroad, 1889 (top). Path of Old Colony Railroad, 1923 (bottom). (Sanborn Map Company)

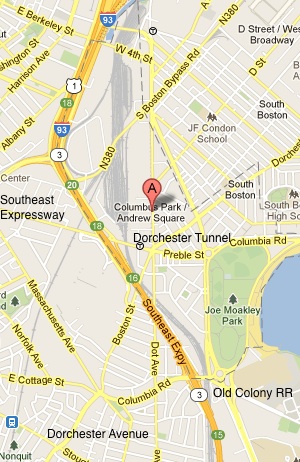

The residents of Andrew Square would have been unlikely to use the railroad because of its cost barrier. Presumably, the neighborhood supported the manufacturing businesses north of Alger Street and by Fort Point. For example, on the 1889 map a Lincoln & Dodge Foundry is adjacent to Alger Street (Figure 3). Employments were in walking distance to Andrew Square’s residents and using the railroad would have been an unnecessary expense. One potential benefit to the residents was construction jobs. That aside, the railway was noisy, polluting, and located extremely close to residences (Figure 4). The municipality was certainly able to impose the project on the neighborhood because of it was of low status. The transportation projects constructed during the 20th century, the Dorchester Tunnel and the Southeast Expressway, equally disregarded the quality of life of Andrew Square's residents.

Figure 3. Lincoln and Dodge Foundry north of Alger Street, 1889. (Sanborn Map Company)

Figure 4. Old Colony Railroad located next to flats and the Polish Catholic Church, 1923. (Sanborn Map Company)

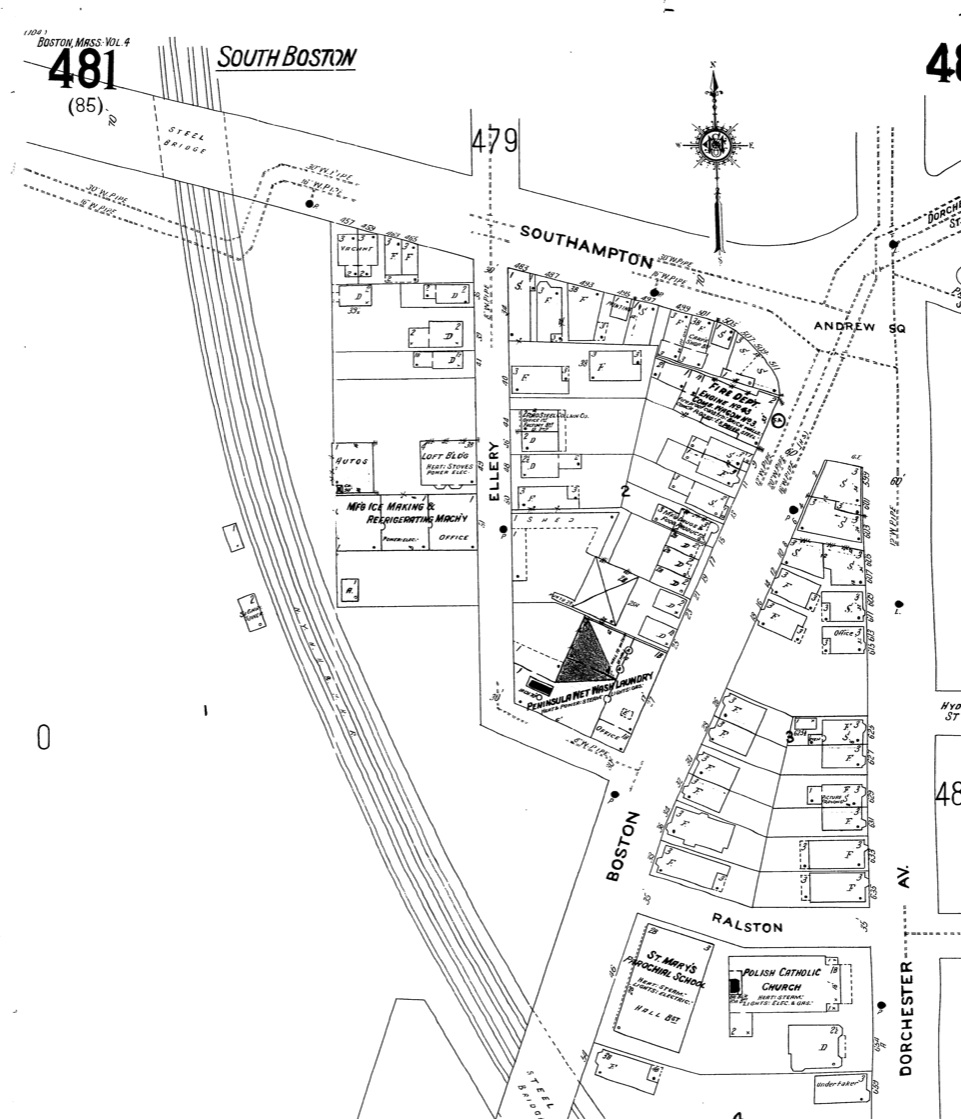

The creation of the Dorchester Tunnel and Southeast Expressway was in response to the growing populations in Boston's suburbs. The Dorchester Tunnel appears on the 1923 map along Dorchester Avenue. It is the only construction project that required the removal of residential properties, a small section of flats bordered by Dexter Street, Ellery Street, and Dorchester Avenue (Figure 5). Part of what is later termed the "Red Line," the subway provided fast transportation for commuters from Dorchester, Quincy, and Braintree. Boston had motivation and a responsibility to provide transportation to people in the newly annexed Dorchester and existing suburbs. While Andrew Square was annexed in 1855, the remainder of Dorchester was annexed decades later. Jackson describes annexation as a trend for major cities during the late 19th century. Two motivations provided are larger organizations can be run more efficiently and that there was competition to be named the nation's largest city (Jackson 144). For comparison, consider that New York City's post-1850 annexations increased the population from approximately 500,000 to 2.5 million in five decades. Dorchester was not part of Boston's tax base and could demand increases in public services. During the next century, between 1920 to 1930, the population in Boston's suburbs grew twice as fast as the population in the city proper (175). The towns of Quincy and Braintree were already along the Old Colony Line, but the subway could provide commuters faster and cheaper transportation. The next bump in transportation is the Southeast Expressway, which begins at Quincy and merges with I-93 by Andrew Square. Its construction between 1954 and 1959 corresponds to enactment of the 1956 Federal Highway Act, which provided funds for highway building. The highway provided more convenient travel into the city for suburban residents but was detrimental to the future economic prospects of Andrew Square.

Figure 5. Dorchester Tunnel Surface Station site in 1889 (top), 1923 (bottom). (Sanborn Map Company)

Land Use

Throughout time, Andrew Square has been composed of mostly low-income residences: tenements, small flats, and federal housing. During the 19th and first half of the 20th century, residents were most likely laborers at nearby iron foundries and other industrial businesses. The area was originally a commercial desert until there was a small, steady increase in businesses first seen on the 1923 map. All of the neighborhoods, excluding the housing project, have existed since at least 1889, the year of the oldest, detailed map that was found picturing Andrew Square. There have been very few changes the buildings in the neighborhood over time, but the few new appearances provide clues about the population.

There are interesting circumstances surrounding the seeming removal tenements on the site between 1889 and 1899. Crabgrass Frontier provides a definition for tenements as a dwelling housing three or more families (Jackson 90). Tenements are noted throughout the site on the 1889 map, usually interspersed with flats and dwellings. There is one section of tenements south of Alger Street that was separate from other housing. This pattern is a departure from the tenement settlement detailed in Crabgrass Frontier, which was an entire neighborhood of shoddy housing (Jackson 116, 117). On the 1899 map only one building was labeled “tenements”. In the curious case of the standalone tenement south of Alger Street, the entire lot was leveled sometime between 1899 and 1923 and not built upon again (Figure 6). That lot bordered a small hub of iron foundries so possibly there were unsafe air conditions. While there were many 20th century initiatives to demolish tenements for a variety of political and humanitarian reasons, the removal of tenements at Andrew Square was decades beforehand. Because so many of the buildings labeled tenements in 1889 are then labeled flats in 1899, it is possible that there was a change to the classification system. The Sanborn Map key did not provide confirmation. The next housing phenomenon was the conversion of residential properties to commercial properties.

Figure 6. Tenement buildings are leveled, 1889 (top), 192 (bottom). (Sanborn Map Company)

The increase in commercial properties after 1889 may have been ushered by the creation of the Dorchester Tunnel. While Andrew Square was not a popular end-destination, there was certainly increased traffic to the area because of the transit line’s presence. In the area immediately surrounding the station there was an electric company, machine company, and a mirror shop (Sanborn Map Company) (Figure 7). Some of these shops occupied previously residential spaces while others were built on the recently filled South Bay. Notably, few of the businesses provide services of benefit to the local residents although they may have provided employment. The churches in the area anchored community life.

Figure 7. Commercial properties near the Dorchester Tunnel Surface Station, 1923 (left), 1950 (middle), 1981 (right). (Sanborn Map Company)

Figure 8. Grace Episcopal Church, 1889 (top). Saint Mary’s Polish Catholic Church, 1899 (bottom). (Sanborn Map Company)

The Old Harbor Village Housing Project was located at Andrew Square because there was an abundance of undeveloped land and it was already a working class neighborhood. In 1937 the Old Harbor Village Housing Project was constructed as part of the U.S. Housing Act of 1937, a federal initiative to provide affordable housing (223). Andrew Square shared many of the characteristics of sites chosen for these projects that were detailed in Crabgrass Frontier (Jackson 227). While not a slum, the neighborhood was low income and near the city center. The portion of the project within the site boundaries is all one-story dwellings (Figure 9). A large complex of apartment buildings lie to the east. While the government agreed that single-family homes were preferable, because the land was near the city center and not in the suburbs there were higher fixed costs and less money for construction (227). The land on which the project is situated has an interesting history.

Figure 9. Old Harbor Village Federal Housing Project, 1950. (Sanborn Map Company)

The housing project lies on original, once partially developed land and part of the filled Old Harbor. On the 1889 map, the original land was the lots bordered on the north by Hyde Street and to the west by Dorchester Avenue. The only buildings erected on the site are along Dorchester Avenue and are small flats and tenements. By 1923 the streets patterns had subtly changed. Lots south of Hyde Street had been combined to form larger plots. The streets between the plots were no longer collinear with the streets north of Hyde Street so new there are a number of newly named streets. Even some existing streets were renamed; for example Abbott Street was renamed Ralston Street. It is not clear what was the intended use of the land. Its decades of vacancy probably made it a cheap steal for the city government. The presence of the housing project deters wealthier residents from entering the neighborhood.

Conclusion

Andrew Square’s evolution through time was most influenced by its position on the border of Boston and Dorchester, proximity to Fort Point, and closeness to the Atlantic. The number of transportation lines on the site increased as the population in the suburbs grew. The noise, pollution, and frequency of outsiders passing through make the neighborhood unattractive for upscale development. The addition of the Old Harbor Village Federal Housing Project in 1937 solidified Andrew Square’s status as a working class neighborhood for the foreseeable future. Decisions about land development and the inclusion of transportation lines from the 19th century have determined Andrew Square’s economic status today.

Citations:

Google Maps. Cartographer. Columbus Park/Andrew Square. Map. 2013. Web. 6 April 2013.

Jackson, Kenneth. Crabgrass Frontier. New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 1985. Print.

Sammarco, Anthony Mitchell. Images of America: South Boston. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 1996.

Sanborn Map Company. Cartographer. Boston Volume 4 Sheet 129. Map. 1889. Web. 5 April 2013.

Sanborn Map Company. Cartographer. Boston Volume 4 Sheet 130. Map. 1889. Web. 5 April 2013.

Sanborn Map Company. Cartographer. Boston Volume 4 Sheet 131. Map. 1889. Web. 5 April 2013.

Sanborn Map Company. Cartographer. Boston Volume 4 Sheet 81. Map. 1899. Web. 5 April 2013.

Sanborn Map Company. Cartographer. Boston Volume 4 Sheet 82. Map. 1899. Web. 5 April 2013.

Sanborn Map Company. Cartographer. Boston Volume 4 Sheet 85. Map. 1899. Web. 5 April 2013.

Sanborn Map Company. Cartographer. Boston Volume 4 Sheet 86. Map. 1899. Web. 5 April 2013.

Sanborn Map Company. Cartographer. Boston Volume 4 Sheet 479. Map. 1923. Web. 5 April 2013.

Sanborn Map Company. Cartographer. Boston Volume 4 Sheet 480. Map. 1923. Web. 5 April 2013.

Sanborn Map Company. Cartographer. Boston Volume 4 Sheet 481. Map. 1923. Web. 5 April 2013.

Sanborn Map Company. Cartographer. Boston Volume 4 Sheet 482. Map. 1923. Web. 5 April 2013.

Sanborn Map Company. Cartographer. Boston Volume 4 Sheet 483. Map. 1923. Web. 5 April 2013.

Sanborn Map Company. Cartographer. Boston Volume 4 Sheet 479. Map. 1950. Web. 5 April 2013.

Sanborn Map Company. Cartographer. Boston Volume 4 Sheet 480. Map. 1950. Web. 5 April 2013.

Sanborn Map Company. Cartographer. Boston Volume 4 Sheet 481. Map. 1950. Web. 5 April 2013.

Sanborn Map Company. Cartographer. Boston Volume 4 Sheet 482. Map. 1950. Web. 5 April 2013.

Sanborn Map Company. Cartographer. Boston Volume 4 Sheet 483. Map. 1950. Web. 5

Sanborn Map Company. Boston Volume 4 Sheet 479, 1981. Map. In Boston, Massachusetts. Sanborn Map Company. 1981. Print.

Sanborn Map Company. Boston Volume 4 Sheet 480, 1981. Map. In Boston, Massachusetts. Sanborn Map Company. 1981. Print.

Sanborn Map Company. Boston Volume 4 Sheet 481, 1981. Map. In Boston, Massachusetts. Sanborn Map Company. 1981. Print.

Sanborn Map Company. Boston Volume 4 Sheet 482, 1981. Map. In Boston, Massachusetts. Sanborn Map Company. 1981. Print.

Sanborn Map Company. Boston Volume 4 Sheet 483, 1981. Map. In Boston, Massachusetts. Sanborn Map Company. 1981. Print.

Appendix:

1889

1899

1950