I. Introduction

Since the area was developed, the Bulfinch Triangle has undergone various stages of growth. These periods of development of the Triangle are closely related to the dominant trends in transportation at different points in time. These changes in transportation have in turn shaped the predominant land use within the site. Some artifacts and traces of the past have persisted through time and continue to exist on the site today. These artifacts and traces serve as constant reminders of the rich history of the site, and link together the different stages of the Triangle’s growth. This has resulted in the Triangle becoming a distinctive and intricately layered urban landscape.

An artifact is defined as anything made by human workmanship. This includes both physical objects such as buildings, as well as abstract concepts such as street names. Artifacts change or disappear over the course of time. Oftentimes, we do not find artifacts themselves, but rather the traces they leave behind. A trace is a visible mark that serves as evidence of the former existence of a particular artifact. A series of artifacts and traces from the same time period is known as a layer. Layers can tell us a great deal about the age of a site and how much that site has changed over the course of history.

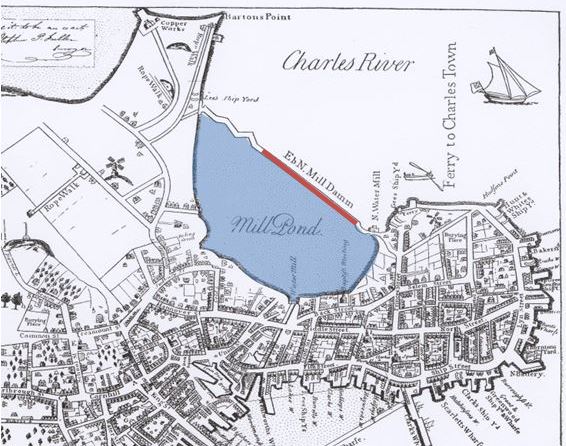

Throughout the Triangle, there exist artifacts and traces of several distinct periods in the site’s history. These periods can be defined by the dominant form of transportation during that time: freight train, automobile, and subway. However there are some older artifacts that exist from when the Triangle was first being developed. These artifacts are names. The name of the Bulfinch Triangle, for instance, is derived from both the architect that designed the layout of the site, Charles Bulfinch, as well as the shape of the site. The Triangle was built on an area of landfill where the Mill Pond used to exist. As such, the site had to conform to the shape of the pond, resulting in the triangular road pattern we see in Figure 1. As we can see, it is possible to derive the history of the Bulfinch Triangle’s development from this single artifact using the plans shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Mill Pond Plan of 1808 (a.k.a. Bulfinch Triangle Plan), by Charles Bulfinch [1]

Figure 1: Mill Pond Plan of 1808 (a.k.a. Bulfinch Triangle Plan), by Charles Bulfinch [1]

We can also use the plans shown in Figure 1 to determine the origin of several notable artifacts: the names of Canal Street and Causeway Street. Prior to the Triangle’s development, the land used to be occupied by a body of water known as the Mill Pond. Causeway Street was built along the dam that separated the Mill Pond from the Charles River. A causeway is the name for a road or railway that runs across a large body of water along the top of an embankment. Looking at the map of the Mill Pond in Figure 2, it is likely that the road that later became known as Causeway Street already existed prior to the development plans made in 1808.

Figure 2: 1722 Map of Boston with the Mill Pond highlighted in blue and the causeway highlighted in red. [2]

Figure 2: 1722 Map of Boston with the Mill Pond highlighted in blue and the causeway highlighted in red. [2]

Looking again at Figure 1, we see the origins of Canal Street’s name. The plans included a canal (blue line) running along the center street of the Triangle. We see in Figure 2 that the Mill Pond was connected to the Massachusetts Bay via canals. It is likely that the canal along Canal Street was intended to maintain the connection between the Charles River and Massachusetts Bay. However, it is unlikely that this canal was ever built (and if it did, it existed only briefly) since later maps show that there is a railway running along Canal Street instead. Regardless of whether or not the canal was built, the street name remains as an artifact that signifies the original purpose for which the street was intended.

II. Transportation Infrastructure

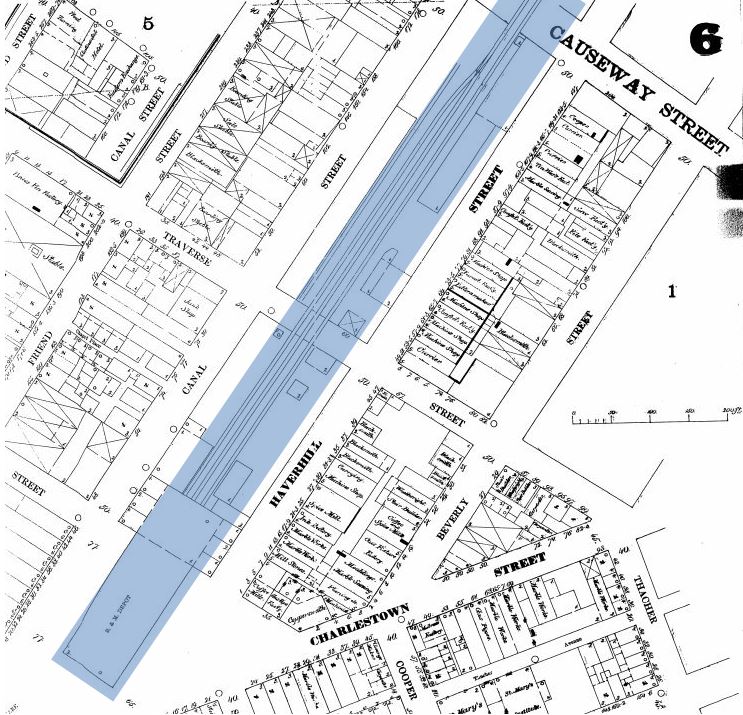

One of the most notable artifacts in the Bulfinch Triangle is the North Station. In the present day, this T stop is a major source of incoming pedestrian traffic to the Triangle. However, the location of the North Station was decided long before it was used as a public transportation station. In Figure 3, we see that rail lines already existed along Canal Street in 1867 before the North Station was built. These had previously been used as freight lines for nearby industry. These freight lines would eventually evolve to become a part of the public transportation system present throughout Boston today. Similarly, the station that these freight lines stemmed from became what is nowadays known as North Station.

Figure 3: 1867 Sanborn map of the Bulfinch Triangle. Rail lines are highlighted in blue. [3]

Figure 3: 1867 Sanborn map of the Bulfinch Triangle. Rail lines are highlighted in blue. [3]

One of the most notable traces that can be seen in the Bulfinch Triangle is the Greenway that cuts across the site. The Greenway was constructed in the early 2000s after the Central Artery Expressway was torn down. The Central Artery was an artifact of the rise of automobiles during the mid-1900s. Because the Central Artery was elevated, large billboards and advertisements would typically be placed on buildings adjacent to the artery so that they would be clearly visible during times of high traffic. Figure 4 shows some examples of billboards found throughout the Bulfinch Triangle today along the streets adjacent to where the Central Artery used to run. It is obvious from the image that these billboards have not been tended to for some time. This is likely due to the fact that it is no longer a suitable location for advertisement since the Central Artery has been demolished. These billboards are both artifacts of the same time period as well as traces of the expressway’s existence.

Figure 4: Artifacts showing the effects of the Central Artery on advertisement location.

Figure 4: Artifacts showing the effects of the Central Artery on advertisement location.

The artifacts and traces relating to infrastructure tend to be of a very grand scale. This is appropriate since they reflect the major changes in transportation that occur within the site over time. These artifacts also tend to be much more difficult and time consuming to change or remove. This makes it much more apparent and significant when such a change happens. The construction of the North Station, for example, transformed the Triangle into a hub for public transportation. The removal of the Central Artery, on the other hand, is a clear sign that the Bulfinch Triangle is currently changing to be more accessible to pedestrians.

III. Artifacts and Traces of Land Use

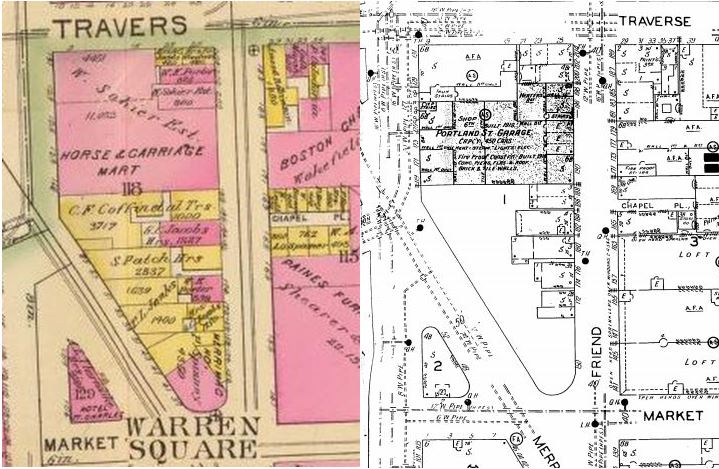

The varying trends in transportation have caused major shifts in land use throughout the Triangle. This has led to the addition, transformation or removal of buildings to accommodate the ever-changing needs of the site. In Figure 5, we see that a large section of buildings (in yellow) have been torn down in order to provide more parking space. This is a response to the increasing popularity and accessibility of the automobile during the 1930s. We can therefore expect to find traces of structures that have been demolished on and around buildings that are still standing today.

Figure 5: Section of the Bulfinch Triangle in 1895 (left) and 1929 (right) showing changes in land use as a response to changes in transportation.

Figure 5: Section of the Bulfinch Triangle in 1895 (left) and 1929 (right) showing changes in land use as a response to changes in transportation.

The pattern presented in Figure 5 is repeated throughout the rest of the site, and traces of buildings that no longer exist are commonly found adjacent to almost every parking lot in the Triangle. One of the most telling traces is the absence of windows along the face of a building. This is clearly shown in Figure 6. We see the parking lot is nestled between two buildings. Both of the building faces adjacent to the parking lot are windowless and in poor condition, suggesting that a building had previously stood there but was torn down.

Figure 6: Parking lot in Lancaster Street in between two windowless building faces.

Another trace of a demolished building is an outline of that building’s roofline along the face of the adjacent building. While this can be seen on both building faces in Figure 6, it is much more obvious in Figure 7 below. In Figure 7 we see the distinct outline of a small building that was deconstructed to make room for more parking. The red outline along the building face indicates the shape of the building that once stood there. The fact that so many buildings have been torn down to make room for parking seems to not only be a result of the rise of automobiles in the 1930s, but also a result of the recent increase in popularity of the Bulfinch Triangle. The proximity of the TD Gardens, for example, greatly increases the need for parking space in surrounding areas to be able to accommodate the large crowds of people that visit it.\

Figure 7: Building face at the intersection of Friend Street and Valenti Way showing the outline of a demolished building.

Figure 7: Building face at the intersection of Friend Street and Valenti Way showing the outline of a demolished building.

Another artifact of land use can be seen when looking at commercial establishments within the Bulfinch Triangle. Over the course of its development, the Triangle’s predominant type of land use has always been commercial. The dominance of automobiles (aided by the availability of parking space) and public travel in the past century has caused the site to have high amounts of pedestrian traffic. This in turn has led the site to greatly favor smaller shops over large businesses. These small shops and businesses are oftentimes owned by single families or individuals. The individuals that own the establishments tend to live on the upper floors of their respective businesses. As a result, the building exteriors vary wildly among the lower floors, but become much more uniform when looking at upper floors. Figure 8 is evidence of Hayden’s statement in The Power of Place that “residents are all active[ly] changing the urban landscape” [4].

Figure 8: Restaurants along Canal Street show a heavily layered urban landscape in which the layers are stacked vertically, with the newest layers on the ground level.

Figure 8: Restaurants along Canal Street show a heavily layered urban landscape in which the layers are stacked vertically, with the newest layers on the ground level.

As shown in Figure 8, the first floor of each of these buildings has a very distinct style depending on the type of business being run in that establishment. However, the upper floors look much older, and are very similar in style and architecture. This suggests the structures were built around the same time. The modern style and relatively new look of the ground floors suggests that these types of establishment change ownership fairly often. This is likely the case, especially since Canal Street has become the center of commercial activity in the Bulfinch Triangle. The sidewalks on Canal Street are much wider than anywhere else on the site, which is likely a response to the increasing pedestrian traffic to the site. This is an indication that Canal Street is an ideal location for small shops and restaurants, which results in a very competitive environment. Any business that is not up to par will quickly get pushed out by a newer business. Each new owner of the establishment would have to change the exterior of the ground floor according to his or her trade. However, there is not sufficient incentive to change the exterior of the upper floors, which may be used as offices or as residences, since pedestrians are not as likely to look up while walking along Canal Street. This results in a very peculiar, vertically layered urban landscape.

This trend is shown once again in Figure 9 below. The image shows the corner of a brewery and restaurant on Canal Street. The most notable aspect of this image is that the outline of old letters labeling this establishment as a chair manufacturer can be clearly seen on the southern face of the building. This shows that industrial land use has indeed moved away from Canal Street and is further evidence of the strong presence of commercial land use on this street. Additionally, we can see that the eastern face of the building (facing Canal Street), looks much newer and well maintained than the southern face. This strongly suggests that Canal Street is indeed the heart of the Bulfinch Triangle, since establishments must maintain their appearance along Canal Street in order to keep their business but the same does not hold true for other streets.

Figure 9: Evidence of changing land use from industrial to commercial.

Figure 9: Evidence of changing land use from industrial to commercial.

The artifacts and traces present in the Bulfinch Triangle suggest an intricate interplay between the infrastructure of the site and its land use. The infrastructure tends to undergo large changes centered around a new development in transportation. The land use shifts more gradually as a response to the changes in infrastructure. Over time, the artifacts and traces left behind by these interactions have built up, resulting in the richly layered landscape that is the present day Bulfinch Triangle. Spirn notes that “landscapes are rich with complex language, spoken and written in land, air and water” in The Language of Landscape [5]. Understanding this language is critical to recognizing how these artifacts and traces give an indication of the current trends present in the site, which help to predict how the Triangle will continue to evolve over time. The construction of the Greenway as a replacement to the Central Artery and the proximity of the Green Line, for example, suggest that the Bulfinch Triangle will continue to receive increasing amounts of pedestrian traffic, further establishing the dominance of commercial land use in the site. This indicates that land use in the Bulfinch Triangle will become increasingly uniform. Regardless, artifacts and traces will remain on the site to remind us of how the Bulfinch Triangle became what it is today.

IV. References:

[1] C. Bulfinch. Mill Pond Plan of 1808. Boston Public Libraray: Norman B. Leventhal Map Center. 1808.

[2] J. Bonner. The Town of Boston in New England. (Boston, 1722).

[3] G. Bromley. David Rumsey Map Collection. “Wards 6, 8”. (Boston, 1895).

[4] D. Hayden. The Power of Place. (1995). pp. 15.

[5] A. Spirn. The Language of Landscape. “The Yellowwood and the Forgotten Creek”. (1998). pp. 11.