Over the course of its existence, the Bulfinch Triangle has been shaped by numerous natural forces. Today it is possible to see evidence of these processes through inspection of signs such as the local vegetation and temperature. While the transformation of the Bulfinch Triangle was driven largely by the efforts of engineers and architects (such as Charles Bulfinch), the natural forces at play during the building of the site took a subtle yet significant toll.

The Triangle represents an area of Boston that has undergone a drastic amount of change. It has transformed from what was once the Mill Pond, a body of water used for hydraulic power in colonial Boston, to the bustling urban landscape that it currently is, full of small shops, businesses and restaurants. The drastic change in the site’s landscape has not only been shaped by natural forces, but it has also greatly affected these natural processes in return. The most significant of these processes include the flow of air and water, as well as the sunlight that permeates throughout the site.

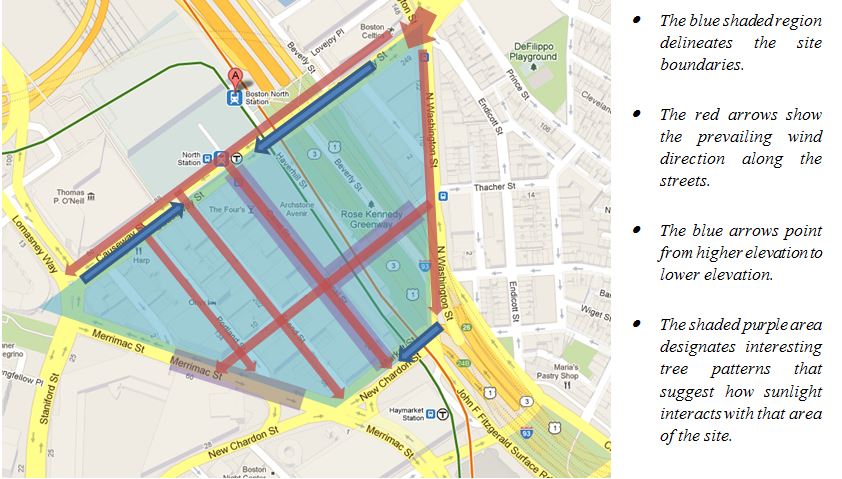

Figure 1 shows a map of the Bulfinch Triangle overlaid with important observations made during site visits. These observations show significant patterns in the site such as wind flow and elevation that are focused at answering how the natural processes of water, air and sunlight have affected the Triangle’s evolution.

Figure 1: Site map displaying site boundaries and observations made during site visits. (Image from Google Maps)

Figure 1: Site map displaying site boundaries and observations made during site visits. (Image from Google Maps)

I. Water

Out of all the natural processes, water has arguably played the most significant and consistent role throughout the site’s history. The Mill Pond was a part of the Charles River, forming a cove along the northern coast of colonial Boston, before it was dammed in 1643. Even after the pond was separated from the Charles, the tides continued to contribute to the site’s growth. The water level in the pond was synchronized with the tides using gates at the mouth of Mill Creek and at the northern end of the pond. The tides would carry water to and from the pond, and the citizens of this area of the city relied on this tidal flow to provide them with many basic necessities, the most important of which were power and waste disposal.

In the eighteenth century, however, the streets of Boston began undergoing a major transformation. All newly paved streets were elevated in the center and sloped towards the sides, where the gutters would be located. This dramatically increased the amount of waste that flowed out of the sewers. The increased waste flow would require the tidal flow to the Mill Pond to be uninhibited in order for the waste to be washed out into the Charles River. On the other hand, the tidal flow needed to be restricted and regulated to be used as a power source. This gave rise to a conflict between the tides being used for hydraulic power and as a source of waste disposal. [1]

It was later in the nineteenth century that the Mill Pond was completely filled using land from the Beacon Hill. This forever changed the role that water plays on the site. The land formerly known as the Mill Pond became disconnected from the tidal forces that had previously given the site purpose. The filled land eliminated much of the natural topography of the wetlands, replacing it with a prominently flat region of soil and concrete.

However, upon visiting the site, I noticed that the topography is not as flat as one would suspect. As shown in Figure 2, there is a moderate sloping of the streets bordering and within the Bulfinch Triangle. These tend to converge on Canal Street, which runs along the center of the site. This gradual sloping suggests that the topography of the site has changed slowly over time, most likely due to the filled land settling. This has caused the center of the site to sink slightly with respect to the outer perimeter.

Figure 2: Image of New Chardon St. showing the tendency to slope towards Canal St.

Figure 2: Image of New Chardon St. showing the tendency to slope towards Canal St.

The tendency of the streets to slope towards the center of the triangle is further confirmed by the pattern of water flow observed during various site visits. Water from the recently melted snow showed traces of flowing from the elevated site boundaries such as New Chardon Street and Causeway Street towards the centrally located streets such as Canal and Friend Streets. There were visible trails of water leading down these streets, collecting in still pools where drainage was not available. One of these trails is visible in the lower left corner of Figure 1.

The Greenway is a recent transformation that has occurred within the Bulfinch Triangle that could have major implications for the role that water (as well as other natural processes) plays in the site. The removal of the Central Artery which used to pass over that particular area of the site has exposed this area to a massive quantity of water via rain and snowfall. The large plots of soil along the Greenway are continuously enriched with this abundant water supply. This suggests that the young and newly planted trees along the perimeter of the Greenway not only have access to larger plots of soil, but that they in fact also have access to a much higher quality of soil. In the future, these trees can be expected to be much healthier and grow larger than their counterparts along the streets of Boston.

Additionally, several streets within the Bulfinch Triangle show intricate networks of cracks that are not only a result of climate, but possibly water as well. During the winter, the low temperatures can cause the asphalt on the roads to contract [2]. Occasionally, this leads to fracturing of the asphalt, with the resulting crack propagating along the road. If a still pool of water were to collect over these cracks, it could later freeze and aid in propagating the cracks even further.

Water has played an extremely diverse and important role throughout the history of the Bulfinch Triangle. Even though the site is no longer a major source of water and hydraulic power, water continues to shape the site in subtle, yet impactful ways.

II. Air

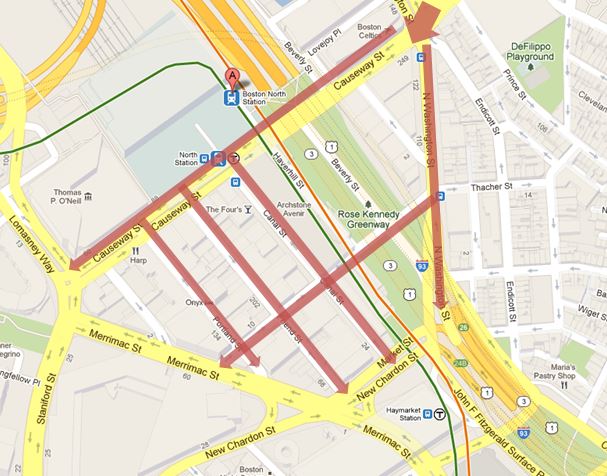

The map portrayed in Figure 3 shows significant wind patterns observed within the sight. The most prominent wind can be felt on the northeastern corner of the site, on the corner of Causeway Street and North Washington Street. It is at this point where the incoming offshore wind first comes into contact with the Bulfinch Triangle.

Figure 3: Site map showing prominent wind flow (Image from Google Maps)

Figure 3: Site map showing prominent wind flow (Image from Google Maps)

The wind patterns within the Bulfinch Triangle are a product of the site’s unique shape. Due to the break in the city structure present at the corner of Causeway and North Washington Streets, the offshore wind is split into two diverging paths. The wind moving along Causeway Street is diverted into the north-south oriented streets, while the wind along North Washington Street is diverted onto the Greenway. The wind flowing through the Greenway is later redirected along Valenti Way. This eventually crosses paths with the wind flowing south along Canal Street, forming a much more noticeable wind current at the corner of these two streets.

The installation of the Greenway and the deconstruction of the MBTA Green Line overpass have greatly changed the wind patterns within the Bulfinch Triangle. The MBTA overpass ran above Causeway Street and was replaced with an underground tunnel in June 2004. When the MBTA overhead pass was still in place, it created a major wind tunnel along Causeway Street [3]. This means that a significant portion of the offshore wind ended up flowing along Causeway Street. This wind would then be redirected to the north-south oriented streets, such as Canal Street. Additionally, any wind along North Washington Street that would have been redirected onto the east-west oriented streets would have been impeded by the Central Artery overpass. These two factors combined resulted in the wind flow being much more prominent from north to south when walking along Canal Street (and other similarly oriented streets).

Nowadays, these two effects are negated. The lack of an overpass along Causeway Street prevents wind from tunneling in that area, since the street is very wide. Additionally, the Greenway provides an enormous open space for wind to flow unimpeded. Therefore the wind patterns in the Bulfinch Triangle are significantly less skewed in the north-south direction than they were in recent years. Additionally, since the vehicles that used both the MBTA overpass and the Central Artery are now using underground tunnels, the quality of the air in the site as a whole has improved due to reduction of car and train emissions. This shows us that large scale construction projects can result in extremely subtle repercussions on the natural processes occurring within the city.

III. Sunlight

When determining how sunlight interacts with a particular area of the city, perhaps the most important source of information lies in the vegetation around that particular site. The relative health and size of trees in different areas of the city can provide great insight towards observing how the sunlight penetrates different regions of a particular site. It is for this reason that I took special note of the trees that were present within the Bulfinch Triangle.

Most of the north-south oriented streets within the Bulfinch Triangle are fairly narrow, therefore not providing enough space to plant trees along the sidewalk. The exception to this trend is Canal Street. Canal Street is perhaps the most popular and heavily trafficked street within the Triangle, holding a diverse collection of small shops and restaurants. It is no coincidence then that Canal Street is also the widest street. Because of this, the sidewalks on Canal Street have room for a total of three rows of trees, two on the north-facing side and one on the south-facing side.

When I first walked onto Canal Street, the first observation that came to mind was that the trees on the south-facing side were much smaller than the trees on the north-facing side. Since the south-facing side tends to get more sunlight, this pattern (shown in Figure 4) runs contrary to common intuition.

Figure 4: South-facing tree line along the northern half of Canal Street.

Figure 4: South-facing tree line along the northern half of Canal Street.

The answer to this anomaly lies in observing how the tree pattern on the south-facing side of Canal Street changes as you move from the northern end of the street to the southern end. The south-facing trees on the southern end of this street are the exact opposite of the trees described above. These are shown below in Figure 5.

Figure 5: South-facing tree line along the southern half of Canal Street.

Figure 5: South-facing tree line along the southern half of Canal Street.

It is evident from the image above that the south-facing trees along the southern end of Canal Street are receiving a healthy amount of sunlight. Furthermore, the north-facing trees on both the northern and southern ends of the street show a tendency to lean towards the north, which is in agreement with the fact that the southern-facing trees are receiving more sunlight. This drives us to the conclusion that the south-facing trees on the northern end of the street are healthy, and were simply planted at a different time than the rest of the trees on Canal Street.

Both sides of Canal Street receive a healthy amount of sunlight due to the extended width of the street and sidewalks. The buildings along the other north-south facing streets are more clustered together (shown in Figure 6 below), and the lack of trees along any of those streets suggests there is both insufficient space and sunlight to allow for healthy vegetation growth.

Figure 6: Medford Street: an example of a street that is too narrow for successful tree growth

Figure 6: Medford Street: an example of a street that is too narrow for successful tree growth

Another structure that has greatly affected how sunlight reaches the Triangle is the Suffolk Probate and Family Court. This enormous courthouse looms over Merrimac Street and casts an imposing shadow. There is a line of planted trees running along the north-facing wall of this courthouse. These trees are small and appear relatively unhealthy. The trees on the south-facing side of Merrimac Street, opposite to the courthouse, are slightly larger but do not appear to be faring much better. Normally, a row of buildings would allow sunlight to penetrate through the spaces between the buildings. However, since the courthouse is just one continuous building and Merrimac Street is not nearly as wide as Canal Street, it is likely that Merrimac Street is not exposed to enough sunlight over the course of the day to sustain the trees that are attempting to grow there.

The deconstruction and closing of the Central Artery and the MBTA Green Line viaduct may also have significant impacts on how sunlight affects those areas of the Bulfinch Triangle. Naturally, both Causeway Street and the Greenway receive much more sunlight since there is no longer a direct obstruction to the sun’s rays. However, other than the growth of plant life in the Greenway, it is difficult to find traces of the effect the difference in sunlight has had since these changes are relatively recent.

IV. Conclusions

Over the course of time, the Bulfinch Triangle (formerly known as Mill Pond) has changed from being a major source of water used for hydraulic power and waste disposal to being a highly urban center of retail and restaurants. Even before its existence, the Triangle has been defined and shaped by natural processes. In return, the artificial forces driving the growth of the site respond to the natural processes of water, air and sunlight, resulting in the constant evolution of the site, the natural processes that shape it, and the relationship between the two.

V. References:

[1] A. Spirn. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design. (Basic Books, 1984).

[2] J. Elkins. How to Use Your Eyes. (Routledge, 2000).

[3] Z. Kostura. Natural Processes in the Bulfinch Triangle. (2003).