Boston began in approximately 1630 as colonists arrived to the Boston Harbor by boat. They realized it was prime land to build a city since it was readily accessible by boat and was also geographically close to the initial settlements of the present-day United States, and so began a vast project to create and change the land in order to build a city, which is still evolving today. Natural processes are a key aspect to how land is used and how it evolves because the environment is unavoidable and over long periods of time, its impact will be vast and powerful. As a result, the land use will be changed both positively and negatively by natural processes, whether it is desired or not. Additionally, instances can be seen where the planning was not sufficient and nature has had a destructive effect on land use.

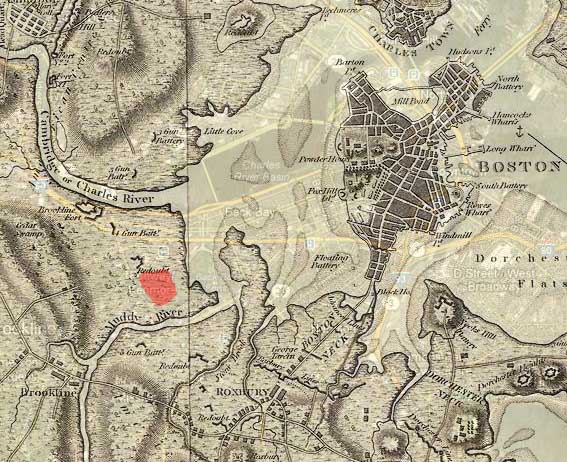

To get the full picture of how the natural environment has impacted the area, it is necessary to analyze the land from the beginning of the settlement of the Boston area. As can be seen in figure 1, which is a map from circa 1800, the land I selected in the West Fens was not filled land like much of Boston; however, it is near land that was partially filled to the East. This land was filled to create the Back Bay Fens, a parkland which snakes through the city of Boston carrying the Muddy River. As will be shown later in this environmental analysis, the Back Bay Fens had a very significant impact on the development of part of my selection of land. Additionally, the area was not nearly as directly connected to downtown Boston until the mid-19th century when the Back Bay was created. This isolation likely caused the late development of the West Fens as compared to the time the downtown area was established. The city had to grow its boundaries outwards, which largely did not occur until the late 19th and early 20th century as transportation became easier and more accessible to the average person.

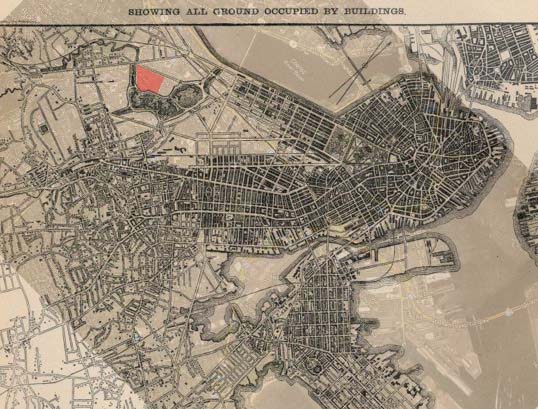

Figure 2 shows that by 1880, the land that makes up present day downtown Boston was all filled and the West Fens was connected directly to Boston. Although the land was formed and at least main roads were in place, it was not highly developed as can be seen from the buildings shown on the 1880 map. The Back Bay Fens was just starting to be developed in this map. The portion of the Back Bay that had the most impact on my selected region was in fact the portion that was already being developed at that point (the section along Park Drive), so that was affecting the land use since the beginning of building development in the West Fens.

Figure 1 - Circa 1800 over present day map ("Map of Boston and Environs, Circa 1800."; “Boston, MA.”)

Figure 1 - Circa 1800 over present day map ("Map of Boston and Environs, Circa 1800."; “Boston, MA.”)

Figure 2 - Circa 1880 over present day map ("World Architecture Images.", “Boston, MA.”)

Figure 2 - Circa 1880 over present day map ("World Architecture Images.", “Boston, MA.”)

Unfortunately, field observations can only be made in the present day so it becomes necessary to look at the clues encoded in the land to figure out how the area has been impacted by nature, and how human development has been targeted to be appropriate for the environment. An excellent candidate for these observations is trees, which are quite prevalent on my selection of land. Trees are unable to adjust on human timescales, and instead change over decades of time very gradually, and are thus a visual representation of the past environment, both natural and artificial. For these reasons, they are invaluable tools in analyzing the environment of any piece of land, and especially how humans have affected that land.

The trees on Queensberry Street are particularly large for street trees, as seen in figure 3, especially given their small plots of land. Although precise dating would require knowledge of tree types, it is clear from their size that the trees on this street are at least many decades old. There is very little land available between the sidewalk and the road for these trees to grow. There is one particularly large tree which shows how this space restriction has affected its growth, as seen in figure 4. The free land not occupied by sidewalk for the tree is very rectangular, and it is obvious even from the surface that the roots have primarily taken only the long axis for growth. This tree is not likely growing into this tilt for sun; despite being a north facing street, other trees on the street were not tilting in this manner. Instead, based on the root structure it looks as though the tree is merely falling over very slowly as a result of its environment to grow on. The large size and well-being of all the trees on both sides of this street may indicate that there is particularly good sunlight on this road, which is running primarily east-west. Since it is often desirable to have quality natural lighting in domestic buildings, this could explain one of the motivations for why the road is almost all apartments.

Figure 3 - Trees on Queensberry Street

Figure 3 - Trees on Queensberry Street

Figure 4 - Leaning Tree on Queensberry Street

Figure 4 - Leaning Tree on Queensberry Street

On Queensberry Street, people have learned to live with the trees. Since there are apartments on both sides of the street, a possible explanation for their persistence against being cut down could be that they provide a buffer from the pollution and road noise produced by cars on the street. The Granite Garden points out that “streets and highways should be located and designed to buffer adjacent homes… from the noise and air pollution they generate” (Spirn, 248). In other locations, however, trees are less desirable and there is evidence of them being reduced in size or even eliminated entirely. There is, of course, a variety of reasons people might remove or cut back trees. Looking at two different cases in my land selection, it is possible to make informed guesses as to why people interacted with the environment in this manner.

Figure 5 - Cut Tree

Figure 5 - Cut Tree

One example of the removal of trees is in an alley on Jersey Street between Park Drive and Queensberry Street as seen in figure 6. This is a tree that is in an alley way and is surrounded on all sides by buildings. Since the tree is not visible from commonly accessed public areas or sidewalks, the aesthetic values of having the tree in full growth are greatly reduced. There is still the view looking out the windows of the apartment buildings to consider; however, it is likely the residents of the buildings prefer to have increased sunlight to improve lighting and energy efficiency rather than having the trees present for aesthetic reasons. Additionally, the alley would not provide nearly as much pollution as a street, so there is not as much shielding required between the roadway and the apartments. There are also several problems with having trees in an area like this. For one, the land around the trees is very valuable as parking space, and the roots of large trees would destroy the parking surface if growth were not limited. Additionally, since the trees are surrounded by buildings, limbs and branches could grow into the buildings causing problems. This is a situation of the destructive nature of the natural process being predicted by people and reduced by proactive measures. Since there isn’t a lot of gain by leaving the trees in their natural condition, it makes the most sense to reduce their growth.

Figure 6 - Removed Trees on Park Street

Figure 6 - Removed Trees on Park Street

Figure 7 - Park Drive lacking trees on south facing side

Figure 7 - Park Drive lacking trees on south facing side

A different example of tree removal can be seen on Park Drive where it makes the most sense that the trees were removed to increase the available sunlight for the buildings. The majority of locations for street trees on this road are all stumps on the side closest to the buildings. Based on building appearance and density, this particular strip on Park Drive is clearly the most profitable land for apartments within my area of study, and the reason is almost certainly because it faces the parkland, and is also south facing. People often desire apartments or houses that have long periods of sunlight because it improves mood, especially for people with seasonal disorders. Additionally, city designers put considerable thought into energy efficiency, and solar energy can improve efficiency both through light as well as heat. As pointed out in The Granite Garden, “[a] building’s size, shape and orientation influence not only the amount of energy required to heat and cool its interior, but also the comfort and air quality of the spaces around it” (Spirn, 246). This makes the strip along Park Drive some of the best land in the downtown area if a high priority is having significant sunlight. Since increased sunlight improves quality of life as well as energy efficiency of the buildings, the land would be more valuable in this location which explains why the apartments on Park Drive are of the highest quality seen in the West Fens site. As can be seen in figure 7, by removing the majority of trees on the south facing side of the street (left side of the photograph), the solar transparency to the buildings is vastly superior than it otherwise would be. To the south, on the right of the photograph, is the parkland. Additionally, there is a reasonably wide buffer between the road and the apartments as compared to Queensberry Street so there likely is not a great need for a shield of trees between the street and apartments.

Figure 8 - Trace snow on south-facing side

Figure 8 - Trace snow on south-facing side

Figure 9 - Nearly a foot of snow on north-facing side

Figure 9 - Nearly a foot of snow on north-facing side

In addition to trees, snow provides an excellent tool to analyze solar patterns since more snow remains where there is less solar energy deposited on the ground. This was especially obvious on Queensberry Street where many of the apartments have boxed in courtyards on the sidewalk. Figures 8 and 9 show the snow depth in the courtyard on the same day and at the same time (late afternoon) on the south and north facing sides of the street, respectively. The depth on the north facing side looks to be almost a foot deep, while there is only trace snow on the other side. These apartments are almost directly across from each other on the street. There are a number of additional observations that can be made from these photos beyond the snow. They were taken at the same time in the afternoon, but the light is clearly substantially brighter on the south facing side of the street, as would be expected based on the sun’s position in the sky. Additional evidence of the solar difference, although not conclusively obvious without observation beyond these photos, is that there are substantially more bushes and shrubs on the south facing side of the street. As mentioned previously, solar aspect is of great importance to the perceived value of land due to the natural lighting and heating effect of sunlight, and this observation shows how vast the differences can be on opposite sides of even the same street.

Figure 10 - Water runoff on building

Figure 10 - Water runoff on building

Sunlight certainly isn’t the only aspect of the natural environment that affects land use. In other examples of natural processes in the West Fens, water can be seen to be impacting the use of the land. Although there are no natural waterways within the boundaries of my area of study, runoff water is an issue for any part of the city since rain fall unavoidably must go somewhere. The presence of water, even if not physically visible at the time of observation, can be seen in a number of locations. A location that stood out as an excellent illustration of the destructive power of runoff water was a building on Kilmarnock Street which has streams of rust coming off of the balconies. The steps below these balconies are also all orange with rust. The need for city designers to address the issues of water is of critical importance; otherwise, significant building and property damage can result.

Some observations of the ground conditions and buildings make me wonder if perhaps there have historically been flooding issues in this land. The alley on Jersey Street between Peterborough Street and Queensberry Street, among several other alleys, shows significant damage to the roadway surface. This could be merely due to poor maintenance; however, there were also unexpectedly large puddles in low spots of the alley, and it hadn’t even rained in the last day at the time of observation. This may indicate that there is poor drainage in the land, which could lead to flooding issues in times of heavy rains or increased river water levels. As additional evidence of possible flooding issues, many of the retail stores seem to be raised above the road level much more than would typically be expected (entrances are above very tilted sidewalks, which appeared to be designed that way rather than settlement of the streets). This was especially noticeable on Kilmarnock Street, although can be observed in other areas. If there have been issues with flooding in the past, it would make sense for buildings to be lifted higher during renovations than they were previously built.

Figure 11 - Church on Park Drive

Figure 11 - Church on Park Drive

Although many times a city’s design requires adaptations to the natural conditions in order to make it fit in with the city plans, there are also many instances where the city is formed around the environment. As discussed in The Granite Garden, parks and natural areas in cities should, and typically are, “designed to fulfill not just one function, but many functions”, with surrounding buildings contributing or benefitting from the open area (246). A great example of this can be seen at the southwest corner of Park Drive, where there is a large open land area which includes some play equipment for children, as well as a church. Since churches are areas where families tend to come together, it could be desirable for people to have it somewhat set away from the urban city environment, making this an excellent exploitation of the natural environment in that part of my site of study. A photograph of the church in its isolated land can be seen in figure 11.

Through these examples, it has become clear even from evidence in my small selection of land how the city has been shaped by natural processes, as well as how the influence of people has shaped the natural processes themselves, especially in the placement and treatment of trees. Cities are built on top of nature, and nature itself is the driving force in gradual changes to the city. Within the West Fens, it seems that the most powerful driving natural force is that of sunlight and the desire to seek the best access to it. These issues end up having dramatic impacts on almost every aspect of the use of land. Land is financially affected both in property value as well as utility costs based on the quality of sunlight, as well as the ability of the property to drain storm water away.

Works Cited:

"Boston, MA." Map. Google Maps. Google, 14 Feb. 2013. Web.

"Map of Boston and Environs, Circa 1800." Large View: Map of Boston and Surrounding Areas, circa 1806. Archiving Early America, n.d. Web. 14 Feb. 2013.

Spirn, Anne Whiston. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design. New York: Basic, 1984. Print.

"World Architecture Images." World Architecture Images. American Architecture, n.d. Web. 14 Feb. 2013.