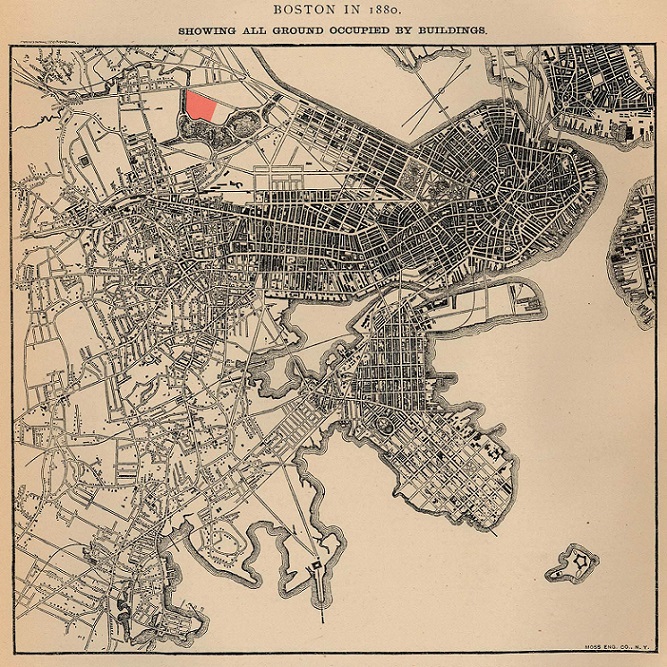

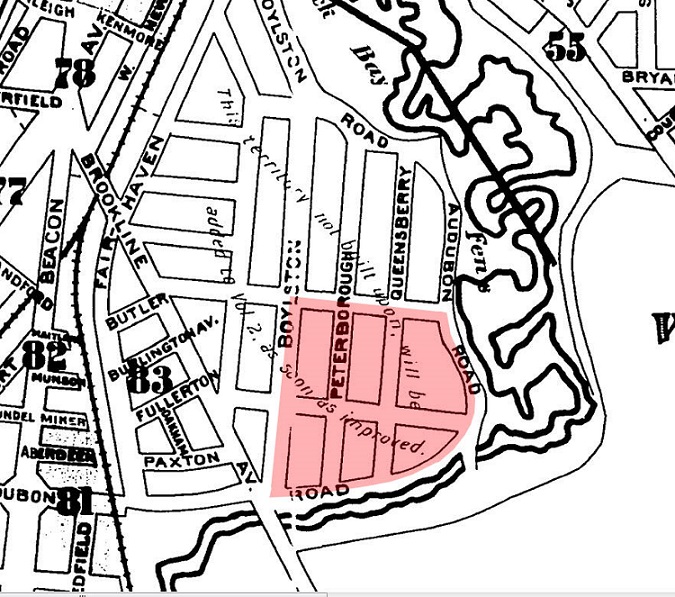

While many of the sites in Boston were already thriving communities by the middle of the 19th century, the West Fens remained unused land during this time period as seen in figure 1, a map from 1880. It was not until nearly the turn of the century that roads were put in to the West Fens (as seen in figures 2 and 3, maps of 1895 and 1897), after which building construction began in the early 20th century. Although the site is now in the heart of a dense city area, there was no city or building development to its north just before the West Fens was first developed, as seen in figure 1, a view of 1880. Based on the progression of the city moving up towards the northwest direction, passing through the West Fens, it seems that its development was part of the natural expansion of the borders of downtown Boston. Given the excellent quality of available land on Park Drive for housing due to the presence of the park, along with the quality of the apartments built throughout the entire site, the initial development was most likely fueled by the new concept of upper middle class apartments in US cities. As mentioned in Crabgrass Frontiers, the “apartment dwelling [for upper middle class residents] only became viable in the 1870s”, before which almost all apartment living was for the lower class (90). Since there are almost no lower class apartments in the West Fens and development began just two decades after the concept of high quality apartments was conceived of, this offers an excellent explanation for the growth of Boston into the West Fens. Jackson also points out that the quantity of upper middle class families vastly expanded in the decades after the civil war (89). This expansion of that sub population would create new demand for the style of apartments found in the West Fens, and may have also helped fuel the expansion of the city through the West Fens area.

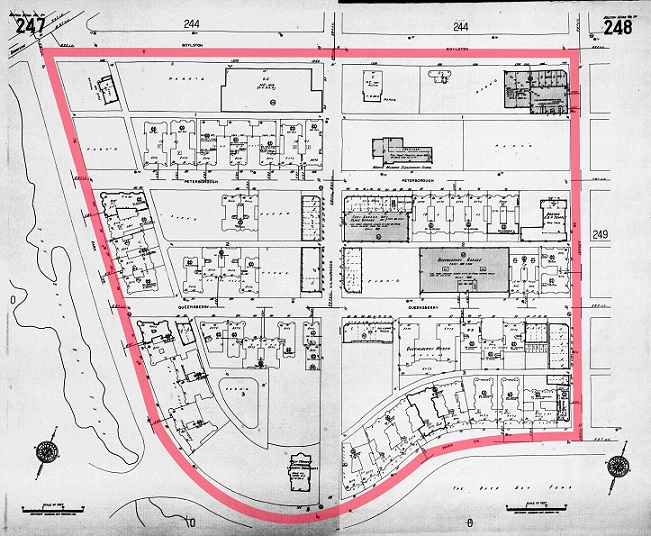

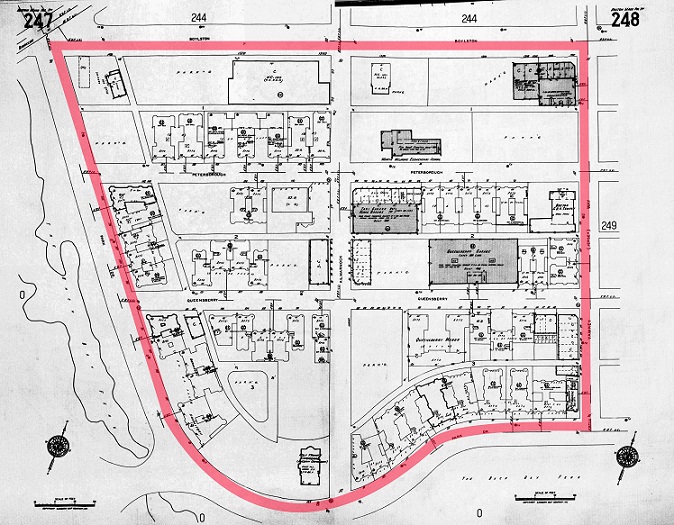

The initial rapid development of the site can best be seen between figure 2, the 1895 Bromley map, and figure 4, the 1937 Sanborn map. This growth, however, is not the most interesting changes in the site to analyze. Nearly any city site will experience an initial rapid growth at some point in history, and some of the reasons for the West Fens’ initial growth were discussed above. What says more about the site as well as the influence of technology and society on that site, however, are the more minute changes that occur after the initial building growth is complete. These types of changes in the West Fens can best be accounted for by addressing the impact that changing transportation technology had on the city. From changes in parking locations to changes in the retail sales industry and the uses of buildings, the transportation revolution can be used to explain a variety of these observations.

Jackson mentions that by 1984, small grocery corner stores had almost exclusively been eliminated in favor of larger supermarkets as a result of the prevalence of owning gasoline powered automobiles (263). This type of change can be seen in a number of locations and times within my site of study. Between the Sanborn maps of 1974 and 1992 (Figures 5 and 6, respectively), it can be noticed that the small subdivided store buildings on the west side of Kilmarnock Street were eliminated leaving the buildings in place but removing the multiple small stores. Comparing 1992 (figure 6) to the present day, there was further removal of small convenience stores on Peterborough and Kilmarnock Street. Although the Sanborn maps unfortunately do not point out the types of retail establishments in buildings, they almost certainly included food, laundry, drug stores, etc. as that was the demand present in small communities like the West Fens in the early 20th century. Some small stores do still exist, however. For instance, on Jersey Street, there is a cluster of small establishments including a 7 Eleven and a laundry facility. Although the majority of shopping is now done in bulk at supermarkets and malls, there is certainly still a convenience factor to having small stores scattered about neighborhoods, so their presence has definitely not been fully eliminated and will likely remain well into the future. Many of the buildings that were previously subdivided storefronts have since been combined to give a larger area and been converted into small restaurants or fast food services. On my site, many of the former community stores on Kilmarnock Street are now cafes or fast food companies. Jackson also explains this as being related to transportation, pointing out that “with the automobile came the notion of ‘grabbing’ something to eat” (263).

As one might expect given the disappearance of small convenience stores, the installation of large supermarket stores can be observed in the West Fens and especially in the immediate surroundings. Between 1937 and 1974 (Figures 4 and 5, respectively), the building at the corner of Boylston Street and Kilmarnock Street can be seen to have grown from a small tire and battery service center to a larger building, which in the present day is a Shaw’s market. Just across the street from my site is an outdoor mall containing a number of large department stores such as Best Buy, Staples, and Bed Bath and Beyond. Before the mid-20th century, large shopping centers were almost exclusively positioned in the urban center of a city but began to spread out into residential areas during the era between the world wars (Jackson, 257). Larger malls in areas immediately surrounding my site, so called “super regional malls” by Jackson, were developed later during the 1970s (260).

Stores were not the only growth to take place on Boylston Street. According to Crabgrass Frontier, before the 1970’s large office and factory buildings were located only in the heart of a city or in highly industrialized areas. This quickly began to change in the 1970’s, after which offices and factories became decentralized from the downtown city and moved outward from the center of the city towards suburban areas. This is largely because of the increased availability of communication and transportation infrastructures during this time. Formerly, companies preferred to be entirely in a single location; however, this became unnecessary given these new technological developments, and it was then more beneficial to have branches closer to where employees lived (Jackson, 266). On the West Fens site, a small building on the corner of Boylston Street and Jersey Street which previously contained a number of small partitioned stores was eliminated in favor of a high rise building which now stands in its place. This building contains a medical center, offices, and several food establishments on the ground level. As suggested by Crabgrass Frontier, it is likely many of these offices are satellite locations built to be near residences in the West Fens and surrounding communities.

Of course, as people get cars, there is a need to park the cars. Although subtle, there are some changes in parking availability within my site. The southeastern corner of Queensberry Street and Kilmarnock Street was once a set of small stores; however, the building was eliminated between the time period of 1974 and 1992 (Figures 5 and 6, respectively). This area is near the apartments on both Queensberry Street and Park Drive, and likely served those buildings. Since the middle of the 20th century was a time period when the average person started to purchase and own a car, there would be a rapid demand for parking near apartments and homes. In the present day, the area has been filled with a large apartment building; however, it appears there is indoor parking available in the lower floor of the building which could offset the loss of parking space. This would not have been done earlier since garages did not exist until the 1930’s, with large garages generally not appearing until after the 1960’s (Jackson, 252).

Beyond the parking changes and different business related uses of buildings, there are two remaining changes of interest to structures, both of which are observable between the 1937 and 1974 Sanborn maps (figures 4 and 5 , respectively). One of these is the removal of a voting booth at the corner of Peterborough Street and Kilmarnock Street in the yard of the elementary school building. There are a variety of possible reasons this could have disappeared, but one obvious and likely reason is simply that it became easiest to have people vote in a single more centralized location instead of spreading out small voting booths. This wouldn’t be a problem when people started to get cars during this time span since driving to a more distant location to vote would be easy. The other building change in this category is the installation of the Holy Trinity Cathedral at the intersection of Kilmarnock Street and Park Drive. This church happens to be located near a large clearing with a big parking lot available to the users of the building. Although the actual reason for installation can’t be identified without specific research into the building’s history, it is likely that it was put in during the mid-20th century as a church accessible by commute given the time range of installation and the parking availability. The church at the intersection of Jersey Street and Peterborough Street, on the other hand, has been in place much longer and has very limited parking. It is likely it is more of a community church attended by those who live in the immediate neighborhood.

Almost every change observable in the Sanborn maps of 1937, 1974, and 1992 has been addressed, and nearly all of these can be accredited to potentially being related to the transportation revolution created by the popularity of owning motor vehicles. The ability to easily move about a city opens the door for massive change in the culture of the city, and changes can be seen even on the tiny scale of observations in only a couple city blocks.

Figures (Some of these are available in higher resolution. Click an image to load a full resolution version. Please note that some of these maps were digitally modified to remove page boundaries):

Figure 3 - 1897 Sanborn Map (Boston Insurance Maps, 1897 ed.)

Figure 3 - 1897 Sanborn Map (Boston Insurance Maps, 1897 ed.)

Figure 4 - 1937 Sanborn Map (Boston Insurance Maps, 1937 ed.)

Figure 4 - 1937 Sanborn Map (Boston Insurance Maps, 1937 ed.)

Figure 5 - 1974 Sanborn Map (Boston Insurance Maps, 1974 ed.)

Figure 5 - 1974 Sanborn Map (Boston Insurance Maps, 1974 ed.)

Figure 6 - 1992 Sanborn Map (Boston Insurance Maps, 1992 ed.)

Figure 6 - 1992 Sanborn Map (Boston Insurance Maps, 1992 ed.)

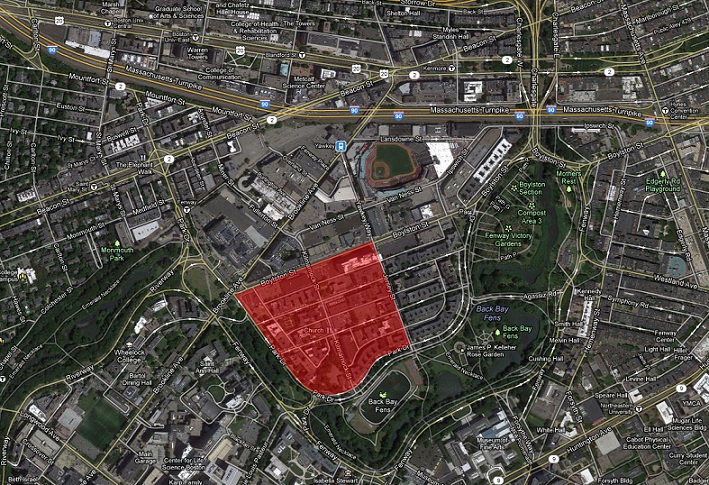

Figure 7 - Present day map and boundaries ("Boston, MA")

Figure 7 - Present day map and boundaries ("Boston, MA")

Works Cited:

"Boston, MA." Map. Google Maps. Google, 14 Feb. 2013. Web.

Boston Insurance Maps. Map. 1897 ed. Vol. 2. Sanborn Perris Map, 1897. 0b. Print.

Boston Insurance Maps. Map. 1937 ed. Vol. 2 North. Sanborn Perris Map, 1937. 247-48. Print.

Boston Insurance Maps. Map. 1974 ed. Vol. 2 North. Sanborn Perris Map, 1974. 247-48. Print.

Boston Insurance Maps. Map. 1992 ed. Vol. 2 North. Sanborn Perris Map, 1992. 247-48. Print.

Bromley, George Washington, and Walter Scott Bromley. David Rumsey Historical Map Collection. Map. Philadelphia: G.W. Bromley and, 1895. 27-28. Print.

Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. New York: Oxford UP, 1985. Print.

Waring, George E., Jr. Boston in 1880. Showing All Ground Occupied by Buildings. Digital image. Wikipedia. 1986. Web. 2 Apr. 2013.