A picture taken of Trinity Church from St James Avenue.

A picture taken of Trinity Church from St James Avenue.

Boston is one of the most illustrious cities of the east coast. Saturated with college students and rich with historical culture, it is a very diverse place to visit or live in. With a location just outside of this major city, it’s fairly easy to dip our toes into all that the metropolitan life it has to offer, but it is nearly impossible to be completely accustomed to the large city after living in it for less than a year. One way to increase understanding of the way Boston works is to focus in on a particular area of Boston in order to recognize and study patterns that are likely seen elsewhere and are affecting other areas of the city every day. Copley Square is an appealing tourist destination and local hub of the city of Boston. Highlighted by the famous architecturally captivating Trinity Church, it functions as both a green space and urban center on the inner edge of Boston’s famous Back Bay region. The Back Bay is an area of the city which was originally completely underwater when the colonists settled here in Massachusetts, thus making it a fascinating piece of land for our site. From the time that the area was settled, the Massachusetts Bay Colony has changed dramatically as a result of the combination of human settlement, development and natural changes over time. The landscape has given its developers enough challenges and so too have the people who have settled in such large populations learned to manipulate and work with the natural environment. The use of Copley Square in particular has been shaped by the natural elements of soil and wind and the hydrosphere, which will be evidenced by a few ongoing issues as well as some minor, noticeable details.

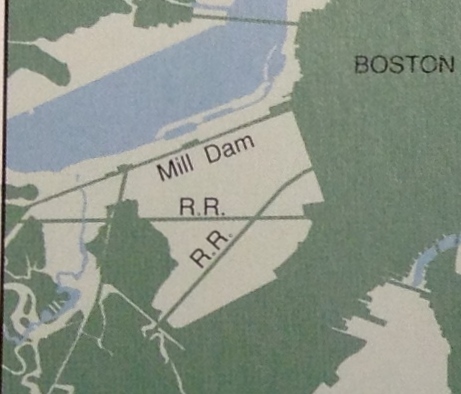

Above is a diagram depicting the fill-in that took place in Boston's Back Bay between 1852 and 1880.

Above is a diagram depicting the fill-in that took place in Boston's Back Bay between 1852 and 1880.

In his book, Mapping Boston, Alex Krieger recounts the story of how Boston came to be the city it is today over a number of years and various developments. In 1630, the city was settled on a sliver of a peninsula, compared to what it is today. This may have seemed like poor planning, but the settlers centered their city on the major port and initially did not foresee the overwhelming amount of growth that would come about through urbanization of their colony. During a booming period of industrialization and immigration of the 17th and 18th centuries, the east coast port saw so much rapid growth that the original piece of land had to be expanded in order to accommodate it. Since the settled area was already surrounded by tidal flats of the Charles River and marshes, the best option was to fill in this land and expand the peninsula[1]. According to Spirn’s analysis on the Back Bay, “original settlers would scarcely recognize the city’s topography and shoreline today”. The Back Bay was one of the first of many major fill operations and it ended up taking several decades of railroad cars travelling back and forth with materials from a village 9 miles away. The filled land would be made up of a combination of gravel, sand and garbage from the city’s residents[2]. The artificial ground that this part of the city was laid upon during the nineteenth century still affects its position today. The soil is less stable, and covering it up with too much pavement is even more perilous.

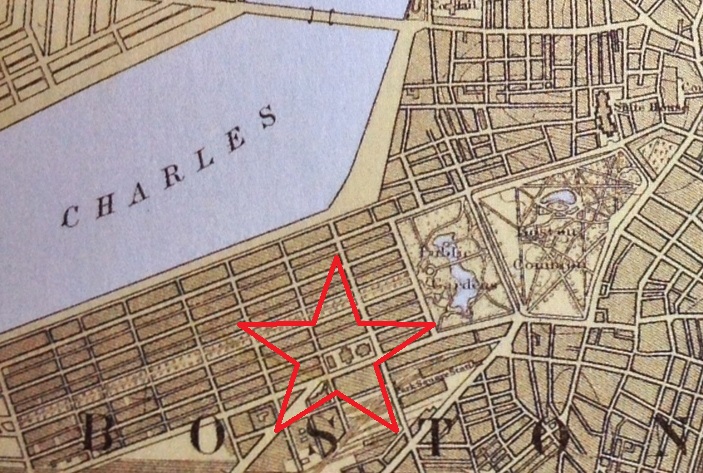

. A map of Boston, showing Copley Square in 1914[3].

. A map of Boston, showing Copley Square in 1914[3].

The various trees which were planted throughout the square.

The various trees which were planted throughout the square.

Copley is a strikingly open square, surrounded by highly developed blocks and densely trafficked roadways. The plant growth is an indication of both human intention and nature’s own willpower. Pictured below are a few of the trees that are planted around the square. These trees are surrounded by concrete walkway, except for the patch of soil they are given to grow. The ones planted in the square seemed much healthier than the ones planted on the sidewalks by the buildings. This is likely because they are given more space and more soil to grow. It is evident that these trees were so healthy that they outgrew the planters’ expectations, because the grates that are placed over the roots to protect and control them are being moved out of place by the growing trees. The trees’ root growth is indicative of the strong powers of nature as well as the adaptability of this particular species. Given only a small space, although it can be concluded that the soil they are planted in is nutritious enough, the trees are growing in the midst of a highly urban environment. There are a few trees which have trunks spilling over their man-made constraints, while there are other trees which are not quite growing to their full potential, presumably because of some lack of soil, sunlight or some other limiting factor. The ones in front of the John Hancock Tower are given plenty of soil, but are constricted by their placement in the shade and lack of stability.

Although Copley Square is not technically a part of the emerald necklace of parkland, which is draped across the city of Boston from the Boston Common to Franklin Park, its development does resemble the mindset that Olmstead had when he envisioned the city. The square was originally proposed by the landscape architect Arthur Shurtleff and was part of a plan to create “rings around Boston” which would connect the city’s outlying neighborhoods to the metropolitan area and thread the open spaces into various city blocks. This incorporation is important for a number of reasons. It is a culturally and socially significant part of the city, but it is also notably beneficial to the air quality and environment of the urban landscape.

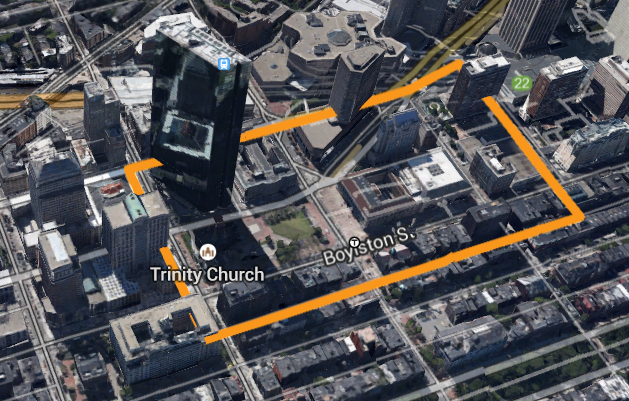

A 3D image of the buildings around Copley Square. Photo courtesy of Google Maps 2014.

A 3D image of the buildings around Copley Square. Photo courtesy of Google Maps 2014.

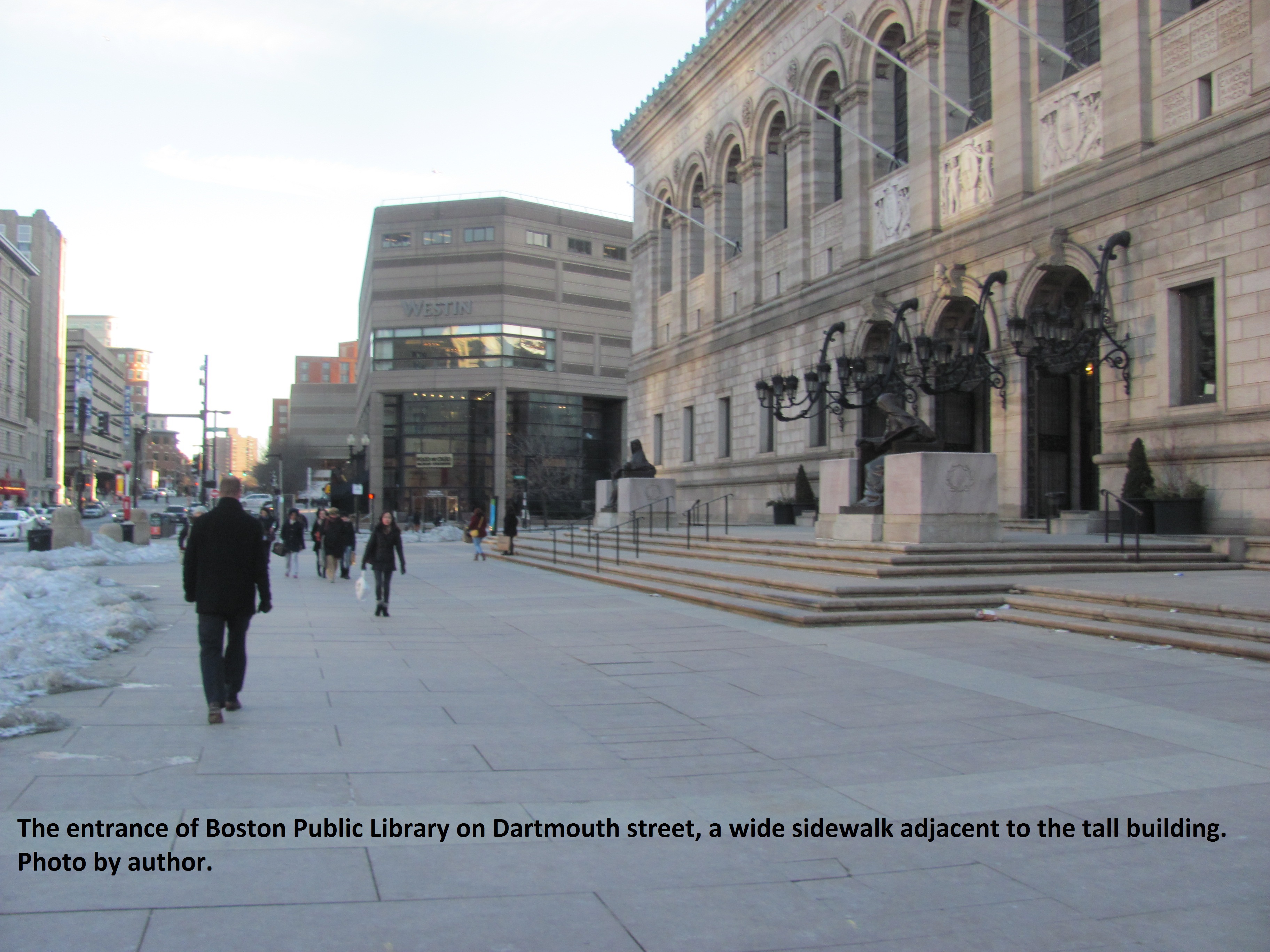

As mentioned earlier, the green spaces in Boston were actually strategically planned out by landscape architects and city planners. These areas may have even become more crucial than Olmstead had even foreseen, particularly with the introduction of the automobile and widespread systems of public transportation. The streets around Copley Square are of particular high vehicle traffic. Pedestrians end up waiting a bit for their traffic signal and the intersection of Stuart Street and Dartmouth Street is a particularly busy and dangerous intersection. The park land breaks up the high concentration of cars and buildings in this part of the city. Walking along the sidewalk of the Boston Public Library on Dartmouth Street, you can pretty much see cars stopping and turning in every which way. Traffic is something that comes with a high density city, and it is also a pattern that can bring many negative effects.

Delving into the problem of air pollution, Spirn notes that there are various approaches that traffic and environmental engineers will take into consideration. Trees are often planted to line the sidewalks of so called stop-and-go roadways. A major roadway is considered a line source of pollution and it is not easy to predict how the pollution will generally disperse, however it is commonly observed that the pollutants will accumulate when enclosed on all sides by buildings. Open spaces and trees in particular are very useful because they remove some of the carbon monoxide and other harmful emissions which would otherwise become a harmful aggregate at the street level[5]. This principle is especially applicable for the case of this site because it includes the beginning of a major piece of infrastructure, Huntington Avenue, which can be fairly complicated to integrate in a city of small streets.

The entrance to Huntington Avenue becomes a high concentration of pavement and automobile traffic. This is in strange juxtaposition to the green square, and it also ends up causing a formidable pattern of winds. I observed that the opening to this roadway, pictured below in my diagram, was exceptionally windy to have to cross. The street is very wide and surrounded by perpendicular buildings which end up funneling the wind down the street. Spirn discussed the vices and virtues of airflow and how it can be controlled. Comfort and accessibility of city streets is something that is both important and takes a lot of consideration. This air flow is helpful to the prevention of pollutant buildup, but it is also a nuisance for pedestrians, especially in the bitter months of winter. An alarming phenomenon occurs when a plaza is placed just below a tall building. The gradient to the concrete causes a steep increase in wind speed and power, which becomes uncomfortable and even dangerous for pedestrians. The area in front of Boston Public Library could almost be such a plaza, similar to the City Hall Plaza Spirn mentions in her book[6]. The large flat area causes extra winds which are immediately perceptible when walking around and which could become a serious problem if nothing is done to ameliorate the situation.

A major consideration to make when considering the growth of vegetation and the elements of a particular environment is how much sunlight gets to an area. The above illustration depicts some of the major buildings around Copley square. These buildings are of varied size and function, though they are all intertwined and affect each other as well as the city. For instance, the different ways the buildings are placed will affect how they impede or allow sunlight and the weather. The largest of the skyscrapers we have surrounding the square is the John Hancock tower, which is a recognizable glistening, soaring building on Boston’s skyline. This one undeniably casts a lot of shade on the sidewalks and the square in front of it. The trees lined in front of this building are significantly weaker than the ones in full sun across the square.

A photo of the trees lined outside the John Hancock Tower.

A photo of the trees lined outside the John Hancock Tower.

A picture of the snow buildup outside the Fairmont-Copley Hotel

A picture of the snow buildup outside the Fairmont-Copley Hotel

.

.

The Copley Square Fountain’s contribution to the public area could be similar to that of Paley Park, as discussed by Spirn in her writings about air quality. Urban heat islands can be uncomfortable places to be outside in and make it difficult to enjoy the great outdoors, however certain strategically planned areas can serve as refuges from the harsh weather that city-dwellers are forced to deal with. Paley Park is a well-designed plaza in the middle of New York City’s lively Manhattan and its tranquil micro-climate attracts visitors during their lunch breaks on sweltering summer days. The appeal of this square has a lot to do with shade and greenery, but its atmosphere is also aided by the misting waterfall. Copley Square, too, is a haven of grass and open land surrounded by tall city blocks and bustling sidewalks. Right next to the square is the beginning of a major crossway, Huntington Avenue, which makes the streets over by the intersection of Stuart Street and Exeter Street very busy and fairly unfriendly to pedestrians and tourists. Luckily for its residents, Boston’s city streets are periodically interrupted with green spaces and recreational areas which break up the monotony of a typical city grid.

From its original arrangement, Boston was intended to have green spaces and open air intertwined with the city blocks and buildings. This has become an important standard as the density of people increased, and as development moved forward so that contractors built structures higher and more rapidly than ever before. Copley Square is not the only urban landscape that is deeply affected by the natural processes that go on around it. On the contrary, every building that is put up and every green space or even sidewalk is interconnected with the land that it is raised up on. Different parts of Boston may not be as affected by the specific characteristics of infill or of a wind tunnel such as the one created on Dartmouth Street, but there are certainly site specific responses that can be observed as well as commonalities between the processes that go on here and elsewhere in the city.

1. Krieger, Alex, David A. Cobb, Amy Turner, and David C. Bosse. Mapping Boston. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999. 2. Spirn, Anne Whiston. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design (New York: Basic Books, 1984), 18. 3. Krieger, Alex, David A. Cobb, Amy Turner, and David C. Bosse. Mapping Boston. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999. 254 4. Krieger, Alex, David A. Cobb, Amy Turner, and David C. Bosse. Mapping Boston. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999. 216. 5. Spirn, Anne Whiston. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design (New York: Basic Books, 1984), 57. 6. Spirn, Anne Whiston. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design (New York: Basic Books, 1984), 59.