Cities are constantly undergoing change. Social, economic, technological, and unpredictable forces shape their existence. By analyzing maps from a site in downtown Boston, the forces which shape cities start to unfold. Sam Bass Warner summarizes the foundation site of Boston in Mapping Boston; “When the Bostonians piled up the rocks and wooden piles to make their Long Wharf in the middle of this little harbor (1711) the center of the city became fixed in the form that we now know. The Old State House (1713), the town market, stood in a straight street on the high ground above the wharf (Figure 2). Later named State Street, it became the business spine of the city. Over the next three hundred years the city spread out from this central axis” (Warner). Using maps from important times in the history of State Street, I will analyze how the early wharves, how the introduction of automobiles into cities, and how historical preservation and tourism can drastically modify and yet preserve aspects of cities.

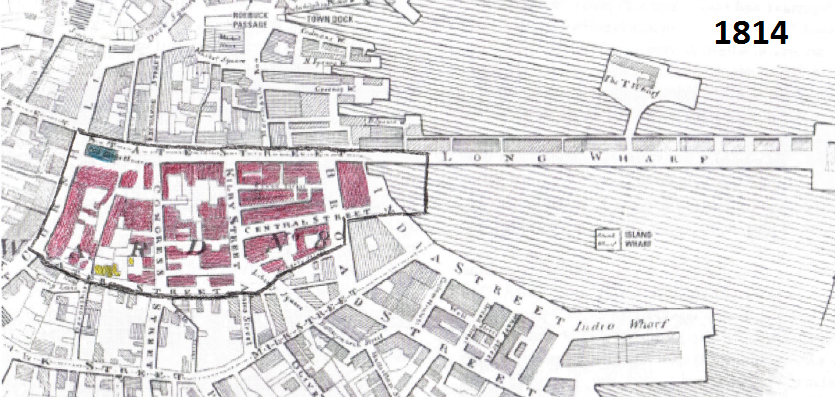

Figure 1: Image from Mapping Boston. The buildings shaded yellow are single family houses. The orange indicates multi-family houses, the red indicates commercial and business buildings, and the blue indicates institutional buildings. Full Source: Sam Bass Warner, Jr. Mapping Boston. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999. pg 25.

Figure 1: Image from Mapping Boston. The buildings shaded yellow are single family houses. The orange indicates multi-family houses, the red indicates commercial and business buildings, and the blue indicates institutional buildings. Full Source: Sam Bass Warner, Jr. Mapping Boston. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999. pg 25.

EARLY DEVELOPMENT: LONG AND INDIA WHARVES

Boston was founded on the Shawmut Peninsula near a water spring. Water Street makes up the southern leg of my site. The area around State Street mostly started out with properties divided between prominent men who first settled in 1630. State Street was mainly a residential area. Figure 1, a map of my site in 1676, depicts the primary residential land use. The streets were laid out around old Indian trials and topological features, and often connected important locations at the time. For example, a road was built from the neck of the peninsula to the meeting house and to the water spring. This road network was quickly set in stone as State Street began to prosper. One interesting pattern that emerged from this map is the location of the first buildings. Most were built lining State Street already setting the stage for prime commercial space.

The land use around State Street moved from wealthy residential houses to dense commercial stores and offices after the construction of the Long Wharf in 1711. A similar effect happened on my site as we discussed in class with different social groups transforming a site's land use. For example, the artists tend to move into warehouses, which brings museums and art institutions, and ultimately commercial entities. On State Street, wealthy residential houses attracted restaurants and stores around downtown Boston. Ultimately the Long Wharf impacted the switch from residential to commercial, but the fact that wealthy residents lived on State Street affected the location of the Long Wharf. As Warner mentioned, State Street became the early spine of commerce in Boston and New England. By the 1720's, Boston was the leading town in North America, largely due to the growth in commerce brought by the construction of the Long Wharf. Large ships now didn't depend on smaller helper boats to unload supplies (Warner). The Board of Trade Building was built shortly after the Long Wharf to help coordinate the commercial traffic and shipments. Figure 5 illustrates the same Board of Trade Building occupying the same location when it was first built during the early commercial boom.

Figure 2: Image from Mapping Boston. Full Source: Sam Bass Warner, Jr. Mapping Boston. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999. pg 47.

Figure 2: Image from Mapping Boston. Full Source: Sam Bass Warner, Jr. Mapping Boston. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999. pg 47.

Shortly after the Long Wharf, the India Wharf was the beginning of the only land filling that happened on my site (Eastern piece including the current U.S. Customs House). It also led to the widening of coastal streets (later named Broad Street) and the construction of a new street, India Street. Similar to the Long Wharf, the India Wharf helped contribute to Boston's economic growth with the China Trade around 1790 and a 41.8 percent increase in population growth (Warner).

One of the major forms of land-making within the first century of Boston's foundation was the construction of wharves. Eventually, enough wharves were made that Atlantic Avenue was built to cut across them. This shortcut eventually led to filling in the space between the wharves and the later construction of the Central Artery in 1950. Despite the fact that these changes occurred off my site, they heavily influenced the change in land use around State Street.

TECHNOLOGICAL IMPACTS: AUTOMOBILE REVOLUTION

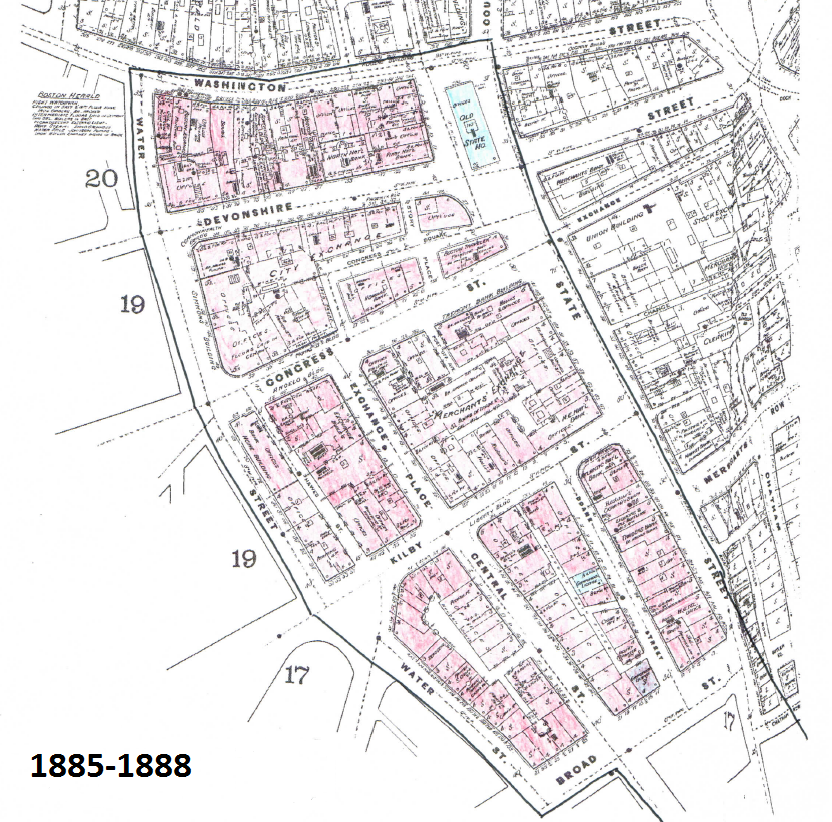

Sometime between 1927 and 1942, the buildings around Central Street were torn down to make room for a parking lot. As seen in Figure 4 depicting State Street in 1942, Central Street doesn't connect Broad and Kilby as it did in Figure 3, the map of 1885. The fact that a parking lot was taking up valuable office space in downtown Boston indicates the possibility that more and more cars were being used as transportation to and from work. Jackson explains how the development of Suburbs and the mass production of the automobile led to a wide acceptance; nearly one in every eight families owned an automobile by 1927 (Jackson). The Central Street parking lot marks the impact of technology and the automobile revolution on my site.

Figure 3: Image from Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps. Full Source: Boston. Map. 1885. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1885-1888 vol. 1, 1885, Sheet 16a". Digital Sanborn Maps.

Figure 3: Image from Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps. Full Source: Boston. Map. 1885. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1885-1888 vol. 1, 1885, Sheet 16a". Digital Sanborn Maps.

Figure 4: Image from Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps (1962). The red indicates commercial business and office spaces, the grey indicates parking space, and the blue indicates a institutional buildings. Full Source: Boston. Map. 1962. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1929-Feb. 1951 vol. 1S, 1962, Sheet 40". Rotch Library.

Figure 4: Image from Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps (1962). The red indicates commercial business and office spaces, the grey indicates parking space, and the blue indicates a institutional buildings. Full Source: Boston. Map. 1962. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1929-Feb. 1951 vol. 1S, 1962, Sheet 40". Rotch Library.

There's evidence indicating a struggle for space between office buildings and transportation. As more people adopt the automobile as the mode for getting to work, more parking is required downtown. However, downtown is prime real-estate for skyscrapers and large office buildings. The parking lot evident in 1942 displaced a significant portion of the Central Street block of office buildings. The struggle for space appears to have found a balance. Later in 1992, the parking garage was put under ground and 75 State Street, a tall new skyscraper, was built on top (Figure 5). Not only is balance of space evident from this change, but the fact that the buildings are growing in size indicates the growth in property value and economic status.

Figure 5: Image from Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps. Full Source: Boston. Map. 1992. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1929-Feb. 1951 vol. 1S, 1992, Sheet 40". Rotch Library.

Figure 5: Image from Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps. Full Source: Boston. Map. 1992. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1929-Feb. 1951 vol. 1S, 1992, Sheet 40". Rotch Library.

As companies and commercial entities grow and shrink throughout time, so do the people occupying the buildings. Some buildings are changed from restaurants and stores to office spaces, or demolished to make room for more office space, as was the case with the Merchants' Exchange. State Street incorporates some of Boston's Financial District, which contains a significant number of buildings used for offices. In figure 6, two separate buildings were combined with land bridges. The distinct change in brick color and pattern each side of both buildings draws attention to the hidden black bridges. Maybe a corporation acquired both buildings, and for the sake of efficiency, decided to renovate and connect them via bridges.

Figure 6: Taken by Jaguar Kristeller

Figure 6: Taken by Jaguar Kristeller

Warner mentions a pressure for local businesses to develop branches across the country (Warner). National companies and corporations started infiltrating Boston. Possible evidence could be that the smaller local restaurants and banks were being consolidated into larger buildings. A shift from building size is clearly evident. In Figure 5, a Sanborn map from 1992, two more skyscrapers were added. The entire Merchants' Exchange block was demolished and built into one large consolidated office building.

Despite the fact that blocks of smaller buildings were consolidated, the same road network pattern initially built on Indian trails and topological paths remained largely unchanged. Why didn't downtown Boston get torn down like the West End during Urban Renewal? Why didn't the popular grid pattern road network slowly work its way into downtown Boston as new buildings were constructed? According to Nancy S. Seasholes in Gaining Ground, Boston was the only large American city without a grid street plan system at its center (Seasholes 2003, 22). Comparing the two most recent maps of State Street, the building foot print hasn't changed significantly. Could it be that there had already been skyscrapers present around State Street, preventing a project to implement grid streets? Or rather than skyscrapers, could there have been important historical buildings that the city of Boston sought to preserve? Does the fact that my site's land use being primarily commercial affect how unchanged its building configuration remained over three-hundred years. I think it's both a combination of economic and social forces causing State Street's road network and building foot prints to fairly constant over three hundred years.

HISTORICAL PRESERVATION AND TOURISM

As national corporations and banks infiltrate buildings around State Street the buildings become connected, renovated, consolidated, and rebuilt. Due to these economic forces, historical value from the period of small stores and businesses owned by successful individual immigrants gets lost. Sometimes it is exposed; while excavating the old Central Street parking lot to prepare for 75 State Street's foundation, wood from the old wharves used for land fill were dug up (Seasholes 2003). However, in most cases the history is buried as buildings are transformed over time. As Warner stated, Boston spread out from my site since its beginning. State Street has been developed throughout the entire life of Boston. One might expect that a cities' downtown would be composed of the most recent buildings. However, compared to most large American cities, downtown Boston is very old. State Street marks the location of the meeting before the Boston Tea Party, the Boston Massacre, and protests for a revolutionary war. The Freedom Trail winds through the center of downtown and the Northwestern corner of my site. The interconnected histories and architecture of old buildings combined with their current use provides evidence of a social pressure, such as tourism, to preserve historical artifacts.

The Old State House, for example, was built in 1713 and still remains a prominent building at the top of State Street. Similar to the Board of Trade Building, the Old State House is present on every map. The juxtaposition between the historical State House and the modern steel skyscrapers depicts some of the social and economic forces molding State Street over time. Historical preservation has impacted development on my site. Rather than tearing down old brick and stone buildings constructed in the 1800's to make room for more offices, many are instead renovated conserving their exterior appearances.

Boston has a particularly well known history, and often attracts tourists. The relationship between tourism and historical preservation and its tremendous effect on my site can be seen with close examination of the US Customs House. The US Customs House was renovated into a prestigious Marriot Hotel. This indicates that the value of land around State Street is high and that tourism has heavily influenced commercial land use. The neoclassical US Customs House was initially built in 1849 on land filled during the construction of the India Wharf. The clock tower was later added in 1915 marking the first skyscraper in Boston (Warner). That fact that the area around State Street is largely financial, but that it still attracts tourists sheds light on the relationship between Boston's present and its history.

Throughout the evolution of State Street, buildings have changed from residential, to individual commercial shops and restaurants, to large financial institutions and skyscrapers. These changes have been shaped by social, economic, technological forces. Historical preservation, tourism, the automobile revolution, and the “wharving out” of coastal properties, shaped my site over three-hundred years since its foundation.

Boston. Map. 1885. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1885-1888 vol. 1, 1885, Sheet 16a". Digital Sanborn Maps. Source

Boston. Map. 1962. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1929-Feb. 1951 vol. 1S, 1962, Sheet 40". Rotch Library.

Boston. Map. 1992. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1929-Feb. 1951 vol. 1S, 1992, Sheet 40". Rotch Library.

Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Fronteir: The Suburbanization of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Sam Bass Warner, Jr. Mapping Boston. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999.