The first time I walked through my site, I saw an amalgamation of old and new buildings with mostly residential and commercial uses. I noted that most of the modern and commercial buildings were clustered on one side of Cambridge Street, while the majority of the old and residential buildings were grouped on the other. I wondered about the source of this divide and I was curious about the few buildings, which broke this trend, like a solitary apartment building standing in a parking lot. I saw the red line disappear into an old residential block, and I wondered how it came to be there and what other changes transportation created on the site. Walking around my site another time, having examined maps of the area from periods in the 19th and 20th centuries, I could see the story, which these remnants of bygone eras tell. Traces and artifacts point to the African American and immigrant populations that occupied the area in the 1800s and early 1900s and the close-knit, working class community that the people created. They point to the destruction caused by Urban Renewal, which tore down the West End in the 1950s. They point to the changes caused by advances in transportation and to the effects of institutional expansion. Today, walking around the site, one can see all of these layers in the current fabric of the neighborhood, and one can speculate about changes that are yet to come.

Map showing current land use and site boundaries (purple)1

Map showing current land use and site boundaries (purple)1 In The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History, Dolores Hayden explains what is known as a “cultural landscape”. The cultural landscape is described by geographer Carl Sauer as “the essential character of a place”, which is shaped by the people who live there and is visible in the traces they leave behind. i Through the 1800s and 1900s, the West End and Beacon Hill were home to a diverse group of people. These groups tended to come in waves: the first was a large African American populationii, the next Irish immigrants followed by Eastern European Jews.iii The cultural landscape of my site took the form of a tight-knit, working class community. Since the 1800s, the area has become wealthier, but Beacon Hill still retains a focus on community that was instilled by the site’s original habitants.

Perhaps the most interesting trace I noticed of the 19th century population was a plaque on the side of a building, which read “ The Museum of Afro-American History; The Abiel Smith School and Museum Store; The African Meeting House; The Black Heritage Trail” (figure 1). The African Meeting House presents an interesting case because it is a trace of multiple populations across the centuries. On the 1885 map, it is labeled as a “negro church”.iv Sometime before 1929, as the African American population moved away from Beacon Hill and the Jewish population grew, the building was converted to a synagoguev, retaining its function as a place of worship, but changing religions. Finally, between 1962 and the present, it became the site of the Museum of Afro-American History. The choice of this building as the location for the museum indicates that Beacon Hill was once home to a large Afro-American community and that this building was of special significance to them.

Figure 1

Figure 1

The creation of the museum in general also points to an important trend from the late 20th century: the effort to preserve historically and culturally significant sites. Hayden describes two proponents of this movement: urban historians, who since the late 20th century have been putting more emphasis on the combination of spatial and ethnic issues, and social movements that have “mobilized against [a] loss of meaning in places”.vi Both of these groups recognize the importance in maintaining buildings and spaces important to the history of an area as a way of keeping its cultural landscape alive.

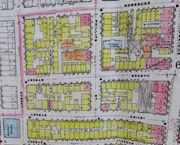

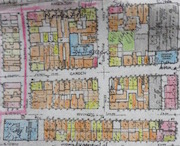

Overall, artifacts in the area point to the idea that Beacon Hill’s cultural landscape is still one of a highly residential community. Most of the buildings from the 1800s are still present, and the majority of those are still residential. Figure 2, which compares maps from 1885 and 1962, displays this continuity.vii Some of the trademarks of residential communities are schools, religious buildings, and community centers, and all of these can be found in the few blocks of Beacon Hill encompassed by my site. Hill House is a community center along Joy Street, which organizes outreach and neighborhood events designed to foster an urban community.viii Around the corner lies Beacon Hill Nursery School. On Philips Street, between Garden and Anderson, lies a synagogue (shown in figure 3), which was built prior to 1929ix to serve the large Eastern European Jewish Community in the area and is still in use today. All of these factors combined suggest that Beacon Hill residents continue to foster a close community and will strive to preserve the area’s history and character.

Figure 2a - 1885 map with residential buildings shaded yellow

Figure 2a - 1885 map with residential buildings shaded yellow  Figure 2b - 1962 map with residential buildings shaded yellow and orange

Figure 2b - 1962 map with residential buildings shaded yellow and orange Figure 3

Figure 3The sense one gets walking though the streets of Beacon Hill, to south of Cambridge Street, is very much that of an urban, residential community, packed with charming brick buildings. However, crossing over to the north side of the street one gets a very different impression. The small city blocks and brick buildings of Beacon Hill give way to superblocks, filled with large, modern buildings for mainly commercial use (see figure 4 for some of the stores located in Charles Plaza, a shopping center constructed between Blossom and Staniford Streets). The difference in appearances is a result of the Urban Renewal project of the 1950s, which razed the West End, which much of the city perceived as a slum, and replaced it with uses meant to stimulate the economy and improve Boston’s image.x Looking down Cambridge Street the contrast is clear, as shown in figure 5.

Figure 4 - shows some of the shops which occupy Charles Plaza, as well as the modern metal and glass buildings which compose it

Figure 4 - shows some of the shops which occupy Charles Plaza, as well as the modern metal and glass buildings which compose it Figure 5 - view down Cambridge Street. To the left (South) are the old brick buildings of Beacon Hill. To the right (North) are the modern buildings and shops in the area that was once Boston's old West End.

Figure 5 - view down Cambridge Street. To the left (South) are the old brick buildings of Beacon Hill. To the right (North) are the modern buildings and shops in the area that was once Boston's old West End.The only trace of the old West End’s residential area I could find north of Cambridge Street are a few solitary buildings standing in the midst of a parking lot. One of these, an apartment building, is shown in figure 6. On the 1885 map, this block, bounded by Blossom, Parkman, N. Anderson, and Cambridge Streets, was densely packed with residential buildings and had a site where a new school was being built.xi Now only 3 remain. The apartment building itself, an artifact from that bygone era, serves as a trace of the rest of the West End. Looking closely at the flat, brick side of the building, one can see the outline of a neighboring building, showing that it was once a part of a row of buildings, rather than an independent structure. There are also traces of windows that have been filled in with bricks. Perhaps this is an indication that the building used to be at the end of a block, then another apartment building was erected next to it as the area developed, and then the other building was torn down again.

Figure 6a - remnant from Boston's old West End standing alone in a parking lot

Figure 6a - remnant from Boston's old West End standing alone in a parking lot Figure 6b - side wall of apartment building

Figure 6b - side wall of apartment buildingThe disparity between these layers of my site (to the south and north of Cambridge Street) indicates a very different development policy instituted on either side of the street. Both areas developed to match the needs of new people and new eras, but in different ways. Beacon Hill preserved its historic buildings, but the use of the structures changed as their old function became unnecessary. For instance, Peter Faneuil School (pictured in figure 7) was constructed as a school in 1909. At some point, the school was deemed unnecessary, but the building (rather than being demolished) was renovated and converted into apartments. New apartment buildings were constructed around it.

Figure 7a - Faneuil School building from 1909

Figure 7a - Faneuil School building from 1909  Figure 7b - view of new residences built around the school from the stoop of the school building

Figure 7b - view of new residences built around the school from the stoop of the school buildingOn the contrary, the city of Boston tore down entire blocks of residences during Urban Renewal to make way for commercial spaces and research centers. In doing so, they displaced all the residents living there and essentially lost the character of Boston’s old West End. Now the area is filled with chain stores. The lesson to take from this is that there are ways to modernize an area without robbing it of its character. It seems, from actions like the creation of the Museum of Afro-American History mentioned above, that people have internalized this idea and hopefully in the future we will avoid large-scale destruction of neighborhoods.

One of the other major trends I noticed on my site was the integration of transportation advances into the fabric of my site. The feature that most stood out is the construction of the red line in 1912, which caused significant changes to the block bordered by West Cedar, Grove, Cambridge, and Philips Streets. On the 1885 map, the block was filled with closely packed residential buildings.xii On the 1929 map, about half of these had been cleared to make way for the T, which enters the ground at this location.xiii Exploring the area by foot, I could see how the line was tightly woven between the existing buildings, as shown in figure 8. Small alleys and communal spaces still exist between the remaining buildings, which provides an interesting contrast to the open space left for the T in one corner of the block. While these buildings and spaces still remain, I imagine that the T must be disruptive to their residents, as it would create large amounts of noise each time it passes by.

Figure 8 – the red line disappears into a group of residences

Figure 8 – the red line disappears into a group of residencesAnother major infrastructure change on my site was the widening of Cambridge Street to accommodate increased traffic flow after the growth in popularity of Ford’s Model T. In this case, I could not find traces of the original road or many of the building’s facades that would have lined it. However, looking back at figure 5, it is easy to imagine that it once would have been much narrower. Finally, the adoption of the automobile as a major method of transportation led to the development of a number of parking garages, parking lots, and gas stations. For instance, residences at the corner of N Anderson and Cambridge Street and at the corner of Grove and Cambridge Street were cleared to make way for a parking lot and gas station, respectively.xiv The gas station, now decrepit, is pictured in figure 9. I wonder what will happen to the space now that it has been abandoned. Perhaps it will be filled with restaurants like those lining other parts of Cambridge Street, or maybe it will be home to a small MGH building. Areas will always need to accommodate advances in transportation and other technologies, and it is interesting to observe the ways this can be achieved. Unfortunately, in these cases, it often involved tearing down buildings to make way for new infrastructure.

Figure 9 – Closed gas station at the corner of Cambridge and Grove

Figure 9 – Closed gas station at the corner of Cambridge and GroveAnother trend that my site has had to accommodate is institutional expansion, specifically the expansion of MGH. This growth can be seen in a few different ways. One is the most obvious – the creation of new, modern research or treatment buildings. For example, figure 10 shows the Richard Simches Research Center, a new research center opened by MGH on the site of some of the old West End residences. This building, from its size and sleek glass and metal design, is clearly modern and does not incorporate any elements of pre-existing structures. On the other hand, two of the three remaining buildings in the parking lot mentioned earlier are now being used by MGH. The West End Club and Winchell School were both present on the site prior to 1929xv, and both are now property of MGH, as shown by the plaques in figure 11. The last change I noticed which was associated with MGH was the additional of parking lots to service the hospital.

Figure 10 – Richard Simches Research Center, situated in the Charles Plaza

Figure 10 – Richard Simches Research Center, situated in the Charles PlazaWhat is interesting about the expansion of the hospital is that it both cleared land to erect new buildings and made use of old historic buildings. This seems to be a reasonable midway point between policies of historic preservation and urban renewal programs. I am interested to see where MGH will expand to the next time it needs a new building. Maybe it will look to the empty lot left by Grampy’s Gas Station. Maybe it will need a larger space and look elsewhere, to another part of the city or to a nearby block with a different current use.

Figure 11a - plaque on old West End House

Figure 11a - plaque on old West End House Figure 11b - plaque on old Winchell School

Figure 11b - plaque on old Winchell SchoolOn my site, one can see distinct layers from various periods in the site’s history: the waves of immigrants entering the area during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the new superblocks created by urban renewal in the 50s, the construction of the red line in 1912 and the addition of parking lots with the rise of the automobile. Despite the marked differences, one can find patterns among the artifacts from each era. The main theme which arose on my site is how to deal with changing demands for land use, whether it be a need to add more residences to an area or a loss in necessity of a certain use, a need to revitalize an area by adding commercial spaces, a need to accommodate changing technologies, or a need for institutional expansion. My site demonstrates three ways of approaching this problem. The first is maintaining the original structures and facades, but changing the use of the space, like some buildings in Beacon Hill. The next is to tear down older areas and replace them with modern buildings and new uses, like what happened during Urban Renewal. The third is a combination of these approaches: to tear down buildings only when absolutely necessary and otherwise try to provide older buildings with new functions. It seems like as my site moves into the future, people will tend to choose the third option. It seems as if there is a growing respect for the historical nature of the neighborhood, which people will keep in mind as they update the area to keep up with changing needs.

iHayden, Dolores. The power of place: urban landscapes as public history. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1995. Print.,17.

iiKrieger, Alex, David A. Cobb, Amy Turner, and David C. Bosse. Mapping Boston. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press], 1999. Print., 8.

iii"Immigrant Era." The West End Museum. N.p., n.d. Web. 4 Apr. 2014.

ivBoston, Massachusetts. New York: Sanborn, 1885, plates 7b, 9a, 9b, and 11a.

vBoston, Mass. Volume 1N. New York: Sanborn, 1929, plates 21, 27, 28, 29.

viHayden, The Power of Place, 40,42.

viiBoston, Mass, 1885.; Boston, Mass, 1929

viii"Hill House." About Hill House. N.p., n.d. Web. 21 Apr. 2014.

ixBoston, Mass, 1929.

xJackson, Kenneth T.. Crabgrass frontier: the suburbanization of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985. Print., 225.

xiBoston, Mass, 1885.

xiiIbid.

xiiiBoston, Mass,1929

xivBoston, Mass, 1885.; Boston, Mass. Volume 1-N. New York: Sanborn, 1962, plates 21, 25, 26, 28, and 29.

xvBoston, Mass, 1929.

Boston, Mass. Volume 1-N. New York: Sanborn, 1929, plates 21, 27, 28, 29.

Boston, Mass. Volume 1-N. New York: Sanborn, 1962, plates 21, 25, 26, 28, and 29.

Boston, Massachusetts. New York: Sanborn, 1885, plates 7b, 9a, 9b, and 11a.

Hayden, Dolores. The power of place: urban landscapes as public history. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1995. Print.

"Hill House." About Hill House. N.p., n.d. Web. 21 Apr. 2014.

"Immigrant Era." The West End Museum. N.p., n.d. Web. 4 Apr. 2014.

Jackson, Kenneth T.. Crabgrass frontier: the suburbanization of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985. Print.

Krieger, Alex, David A. Cobb, Amy Turner, and David C. Bosse. Mapping Boston. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press], 1999. Print.