Introduction

It’s not hard to walk through Beacon Hill and picture myself walking in 1867, while I feel the cobblestones in my feet and glance at the small row houses and the historic lampposts. The south slope of Beacon Hill encompasses several artifacts, layers, and traces that enable this site to contrast its modern surroundings like the financial district or the West End. From the cobblestones in Louisburg Square or Acorn Street, to the vintage lampposts, these artifacts recreate the past and enhance the significance of this particular epitome district. On the other hand, the surroundings display traces of the different forces they have faced: the settling of immigrant population, the appearance of the car, urban renewal and modernization, or even the construction of apartment and office buildings. Meanwhile, Beacon Hill resists significant changes and attempts to maintain its historical landscape. As a result, these artifacts and traces present in Beacon Hill and its surroundings help us understand how different forces have impacted the area. Walking through the site today, it’s easy to notice its immunity to these forces and how it illustrates the trend of historical preservation nowadays.

Layers of The Hill and Its Surroundings

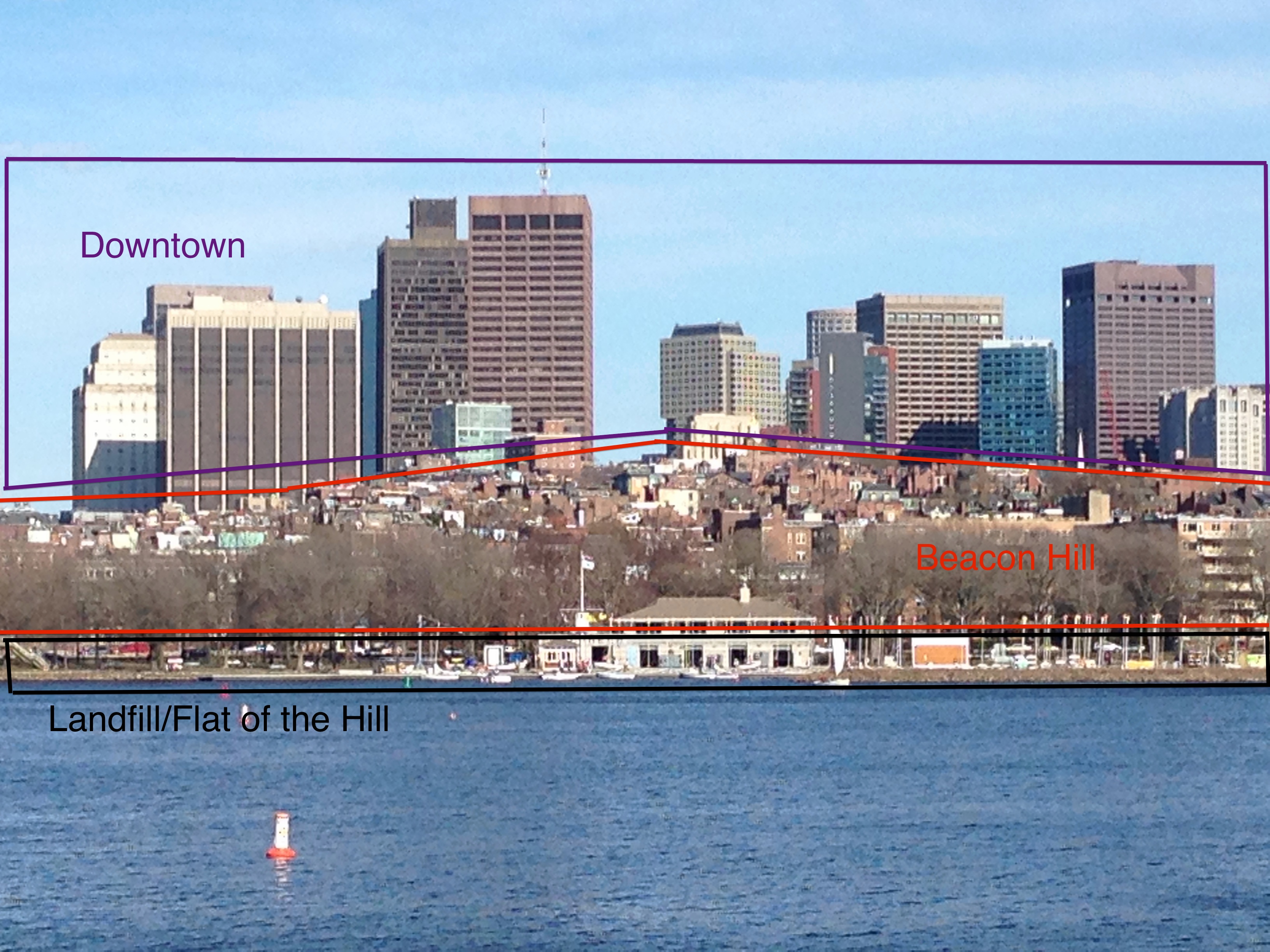

Figure 1: Seen from the other side of the Charles River, there are clear layers portrayed:

Figure 1: Seen from the other side of the Charles River, there are clear layers portrayed:the Charles River shore, Beacon Hill, and the Financial District’s sky scrapers in the back.

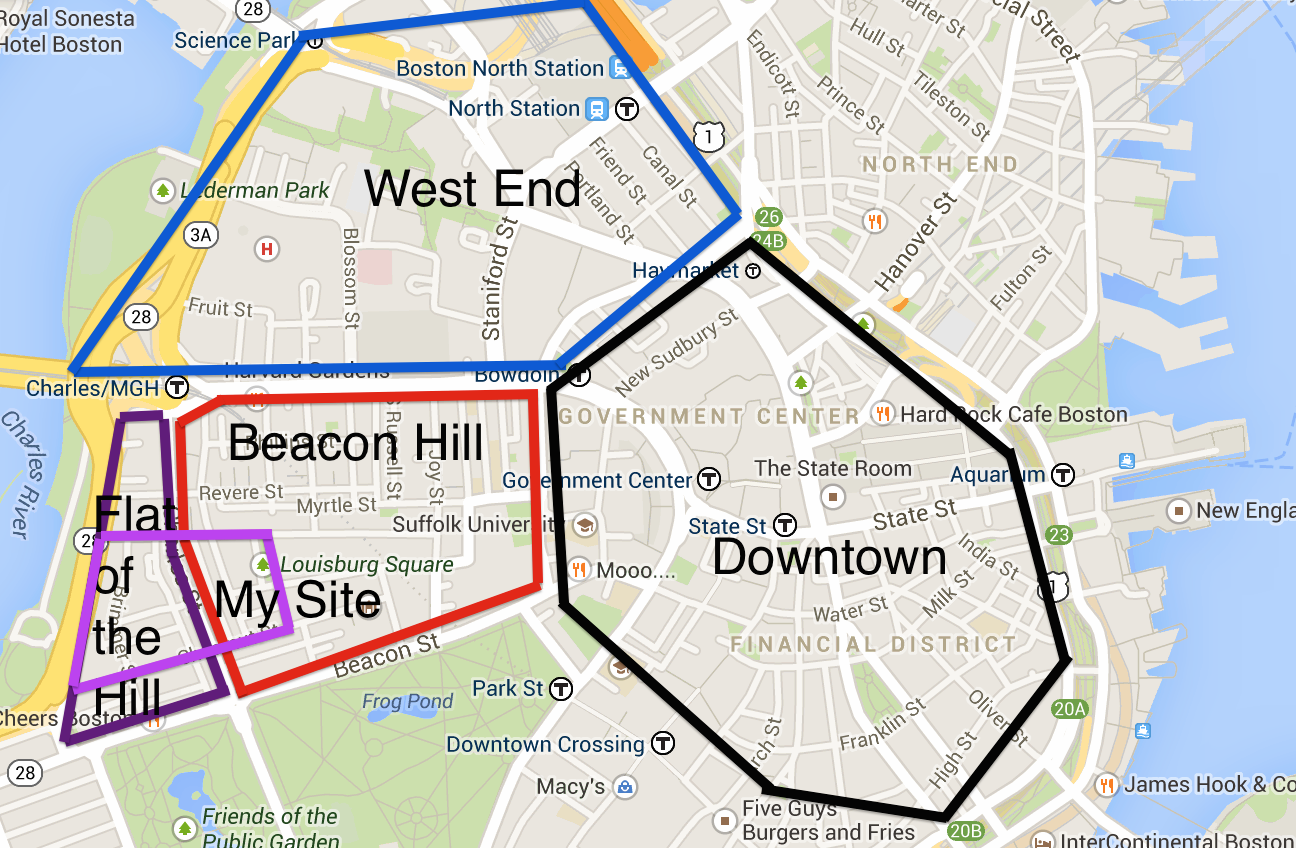

The first time I walked from the Charles/MGH Subway Station to Louisburg Square, I had the sensation of walking through several layers of history. The subway station of the Red Line, a result of massive transportation, modernization, and suburbanization movements, clearly contrasts with the peaceful and noise-less environment of Louisburg Square. Even though Beacon Hill is defined as a hill, by taking a step back and comparing it to its surroundings, it’s easier to define it as a valley in the middle of the modern skyscrapers of the downtown. As seen in Figure 1, Beacon Hill can be seen as a valley of small buildings compared to the downtown in the back. Furthermore, the area can be divided into a series of layers, representative of different periods of history. These layers develop as the effect of different historical processes like the landfill of the Charles River, the reduction of the Tri Mountain, and even the suburbanization movement present in the first half of the twentieth century. As described by Dolores Hayden in The Power of Place, “as the productive landscape is more densely inhabited, the economic and social forces are more complex, change is rapid, layers proliferate, and often abrupt spatial discontinuities result that cultural landscape studies seem unable to address adequately”[1]. These densely populated areas surrounding Beacon Hill enhance the development of said layer, and as a result, we see aggressive change in these areas, be it the West End, the Flat of the Hill, or the financial district. As seen in Figure 3, Charles Street exemplifies a boundary between two contrasting areas within my site: the Flat of the Hill and the south slope of Beacon Hill. At the Flat of the Hill, different populations migrated into this area, enhancing the development of apartment buildings, offices, commercial stores, and churches. However, in the south slope, everything remains the somewhat static: we don’t see changing architecture or churches and we still see the same population profile and the same row houses as in the late nineteenth century.

Figure 2: Walking through the south slope of Beacon Hill, particularly on the Pinckney

Figure 2: Walking through the south slope of Beacon Hill, particularly on the Pinckney and Mt. Vernon Streets, its easy to observe the contrast between the row houses of the

hill and the modern buildings in the downtown.

These contrasts become clear when I walk within the south slope of Beacon Hill. For example, as seen in Figure 2, by looking north through Pinckney Street, one can notice the boundary between the hill and the downtown skyscrapers. This boundary not only explains the juxtaposition present within Beacon Hill and its surroundings, but also serves as an example of a recurrent phenomenon across the east coast of United States. Particularly in the northeast, where most of the cities were established as colonial towns, the historical districts see themselves surrounded by modern skyscrapers. In the case of Boston, the downtown, the landfilled area, and the Charles River happen to abut on Beacon Hill. As seen in Figure 3, there are several areas bordering Beacon Hill that are subject to critical changing forces. The contrast with these areas leads to the development of these layers, and further hint the interplay between historical preservation and urban renewal throughout the twentieth century.

Traces of What Changes and What Stays the Same

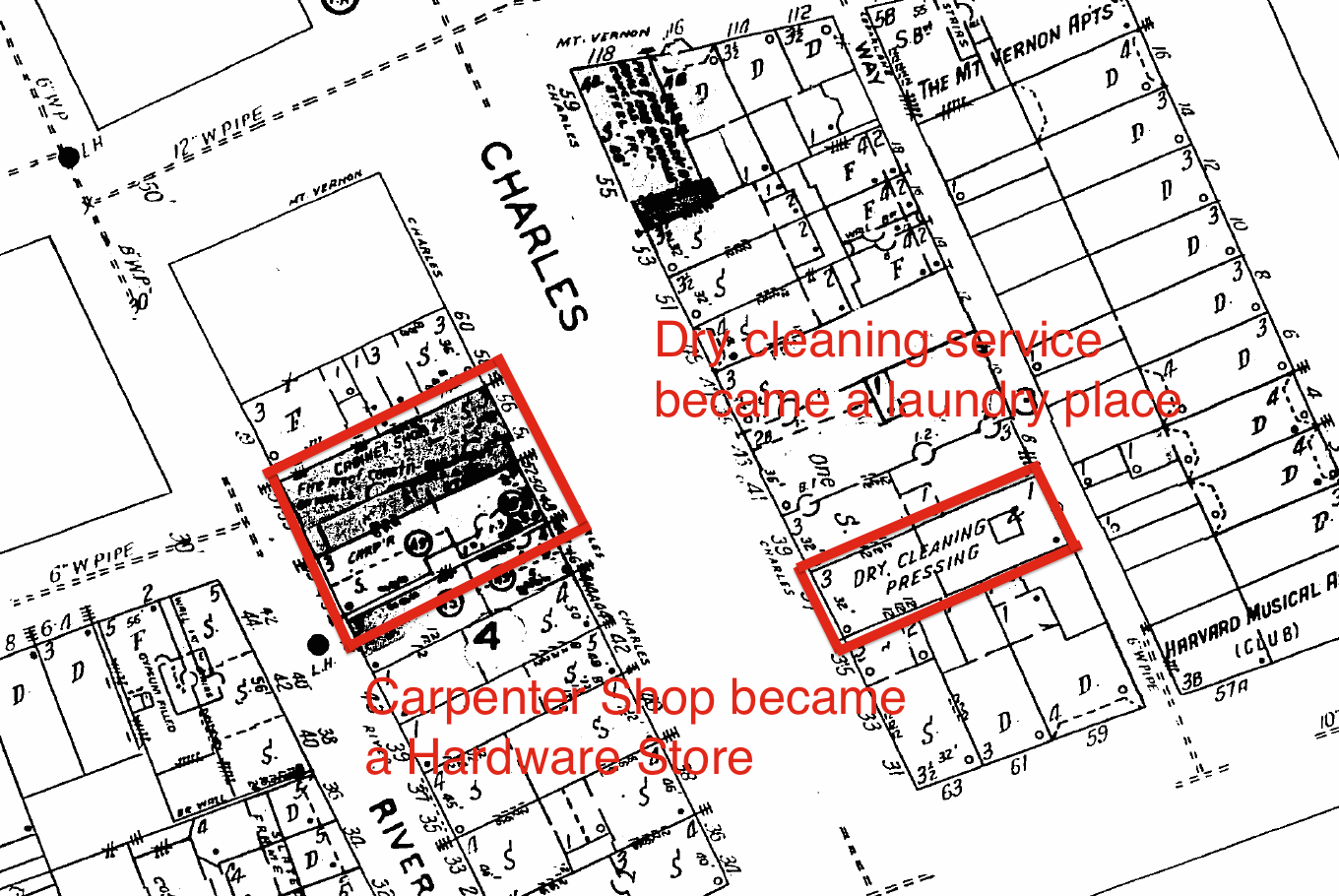

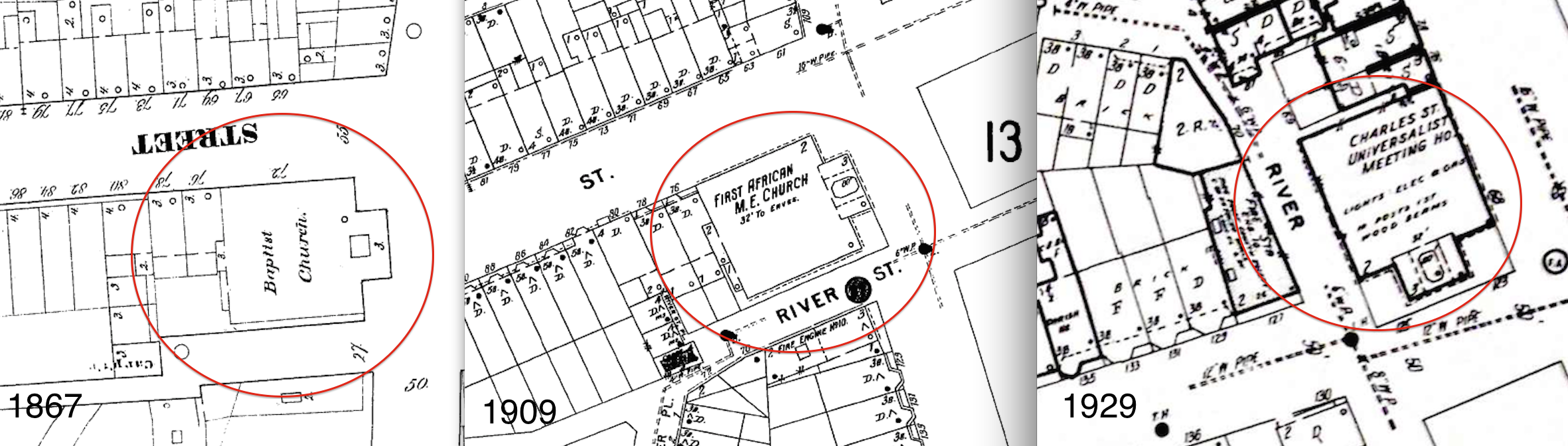

Figure 4: Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from 1909. Even though Charles Street developed

Figure 4: Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from 1909. Even though Charles Street developedas an important commercial street throughout the twentieth century, most of its

businesses remained the same. The carpenter shop and dry cleaning service are two

examples of such phenomenon.

Figure 5: As mentioned in the previous Figure, laundry services and hardware shops

Figure 5: As mentioned in the previous Figure, laundry services and hardware shopsnowadays occupy places that previously had dry cleaning services and carpenter shops,

respectively.

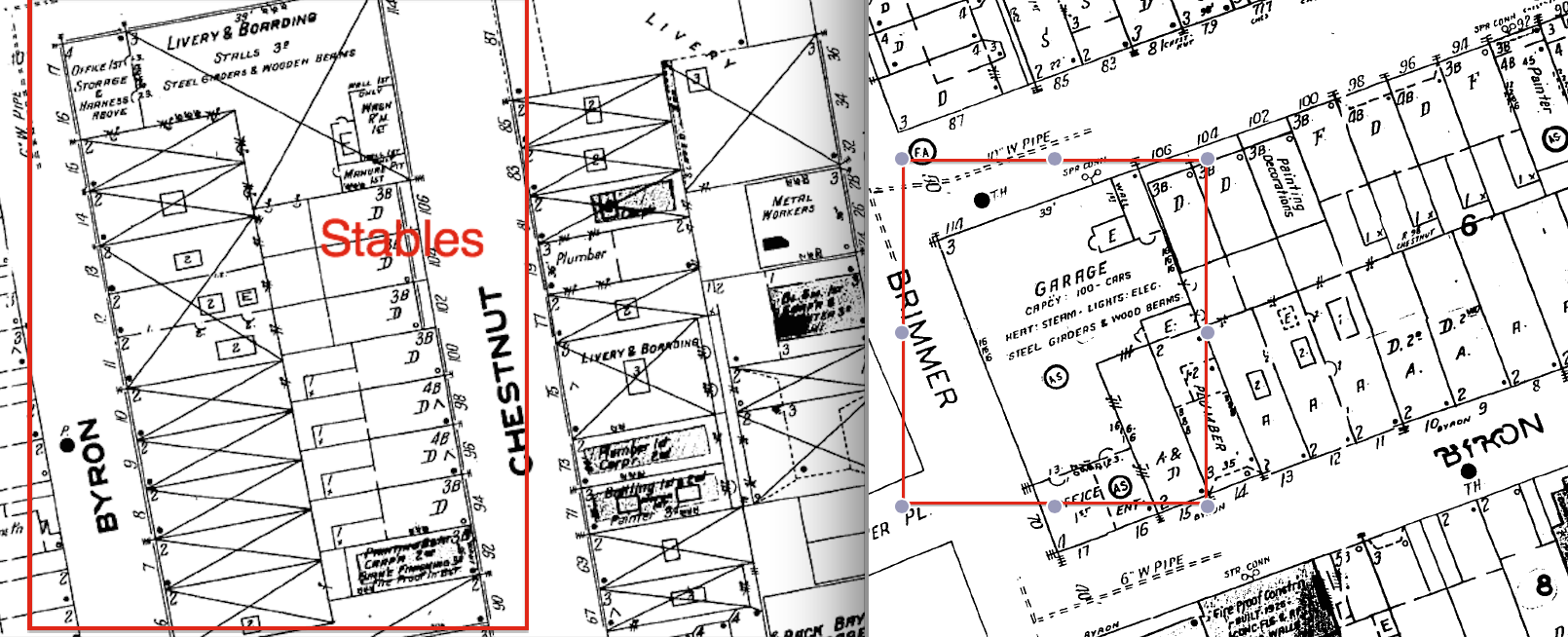

Charles Street serves as one of the boundaries between some of different layers within my site, as described in the previous paragraphs. As a boundary, Charles Street separates the historic south slope from the renewed Flat of the Hill. However, the street itself also develops several patterns due to its contact with these contrasting environments, as well as its development as the commercial street of the area. Even though several of the properties in Charles Street changed significantly in the first half of twentieth century with the construction of apartment buildings, garages, and offices, most of the businesses and uses of the commercial stores still resemble those from the beginning of the twentieth century. For example, as seen in Figures 4 and 5 places which previously had a carpenter’s shop or a dry cleaning service currently have a hardware store or a laundry place, respectively. Therefore, we can see how these stores act as traces of previous businesses, and suggest the continuing predominance of residential services in these stores. Also, taking into account most of the buildings around Charles Street (both in the south slope of Beacon Hill and the Flat of the Hill) continue to serve mostly as residential units, we can expect the purpose of these commercial units to be mostly residential. Furthermore, blocks that had stables in the late nineteenth century and garages throughout the twentieth century continue to have these in the present day. As seen in Figures 6 and 7, the corner of Chestnut and Brimmer Streets continues to serve as a parking lot. This general preservation trend suggests that the denomination of Beacon Hill as a historical district has hindered the changing patterns occurring in the area. As a result, most of the land uses stay the same, and the changes occurring are direct traces of former businesses with similar purposes.

Figure 6: Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps from 1909 (left) and 1929 (right).Even though

Figure 6: Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps from 1909 (left) and 1929 (right).Even thoughthe appearance of the car led to the replacement of stables with garages, these places

stayed in the same place, rather than invading the historical south slope.

Figure 7: The garage that appears in the Sanborn 1929 map is still in place nowadays.

Figure 7: The garage that appears in the Sanborn 1929 map is still in place nowadays. Even though most of the structural changes are subtle in most areas in Beacon Hill, there are significant changes regarding demographics and culture. In particular, the church in the corner of Mount Vernon and Charles Street is a trace of the changing demographics of the area (Figure 8). Since the nineteenth century, this church has been affiliated as a Baptist Church, an African Methodist Episcopal Church, and currently a Quaker Meeting House. Its change of denomination not only reflects the changing demographics of the region, but also changes the cultural landscape of the region. In Hayden’s The Power of Place geographer Carl Sauer defines cultural landscape as the “combination of natural and man made elements that comprises, at any given time, the essential character of a place”[1]. In this case, due to the lack of architectural and land use changes in Beacon Hill throughout the twentieth century, the change of denomination of this church becomes an important hint of predominant patterns. In this case, the church acts as a trace to illustrate the exodus of African American culture from the north slope of Beacon Hill to Boston’s South End [2]. Therefore, the traces present in Beacon Hill suggest the current steady state of the area and the possible absence of change in present and future times. Even though in the past the area experienced several topographic, demographic, and technological changes, the essence of the area remains the same, and as a result, it’s likely that it will remain the same for another one hundred years.

Artifacts That Maintain the Essence of the Past

Figure 9b: Picture of Louisburg Square, Beacon Hill

Figure 9b: Picture of Louisburg Square, Beacon Hillin 1930 taken by Abdalian, Leon H. (photographer).

From: The Boston Public Library, Print

Department.

Figure 9a: Picture of Louisburg Square, Beacon Hill

Figure 9a: Picture of Louisburg Square, Beacon Hillin 2014. Regardless of the 84 year difference

(1930 and 2014), the essence of

Louisburg Square remains practically unchanged.

Another fact I pondered while I walked through Louisburg Square and the south slope in general was why people nowadays value historic architecture the way they do. Nowadays, a person is willing to pay over ten million dollars to have a house in Louisburg Square. Only the richest people in the country can afford this. However, going back one hundred years to the beginning of the twentieth century, I am sure more than one person would have paid that amount of money to demolish these houses and build a modern sky scraper. The value that we give today to places like Louisburg Square or Acorn Street is due to the presence of several artifacts that enhance the historical aspect of the place. Some of these artifacts like the cobblestones in the street, the row houses, or the lampposts make the place look as though it were built in the early nineteenth century. Indeed, in Figure 9 we can observe how there is barely any change between Louisburg Square in 1930 and in 2014.

Cobblestones and Lampposts in Acorn Street

Figure 10: With its cobblestone-paved street and

Figure 10: With its cobblestone-paved street andantique lampposts, Acorn Street becomes one of the

few streets in Boston that strongly characterize the

cultural landscape of early nineteenth century Beacon Hill.

One of the unique features of Louisburg Square and Acorn Street were the cobblestone-paved streets. Regardless of whether these were paved during the settling of the area or during the twentieth century, they serve to enhance the historical essence of these places. Why cobblestones? In fact, cobblestones frequently found in Boston’s soil, and as a result often used to pave early roads or to build walls [3]. (Figure 10) This phenomenon is only present in these two places, further adding historical value to them. However, it’s common to see the use of unique paving materials in historic roads or neighborhoods to add said value to them.

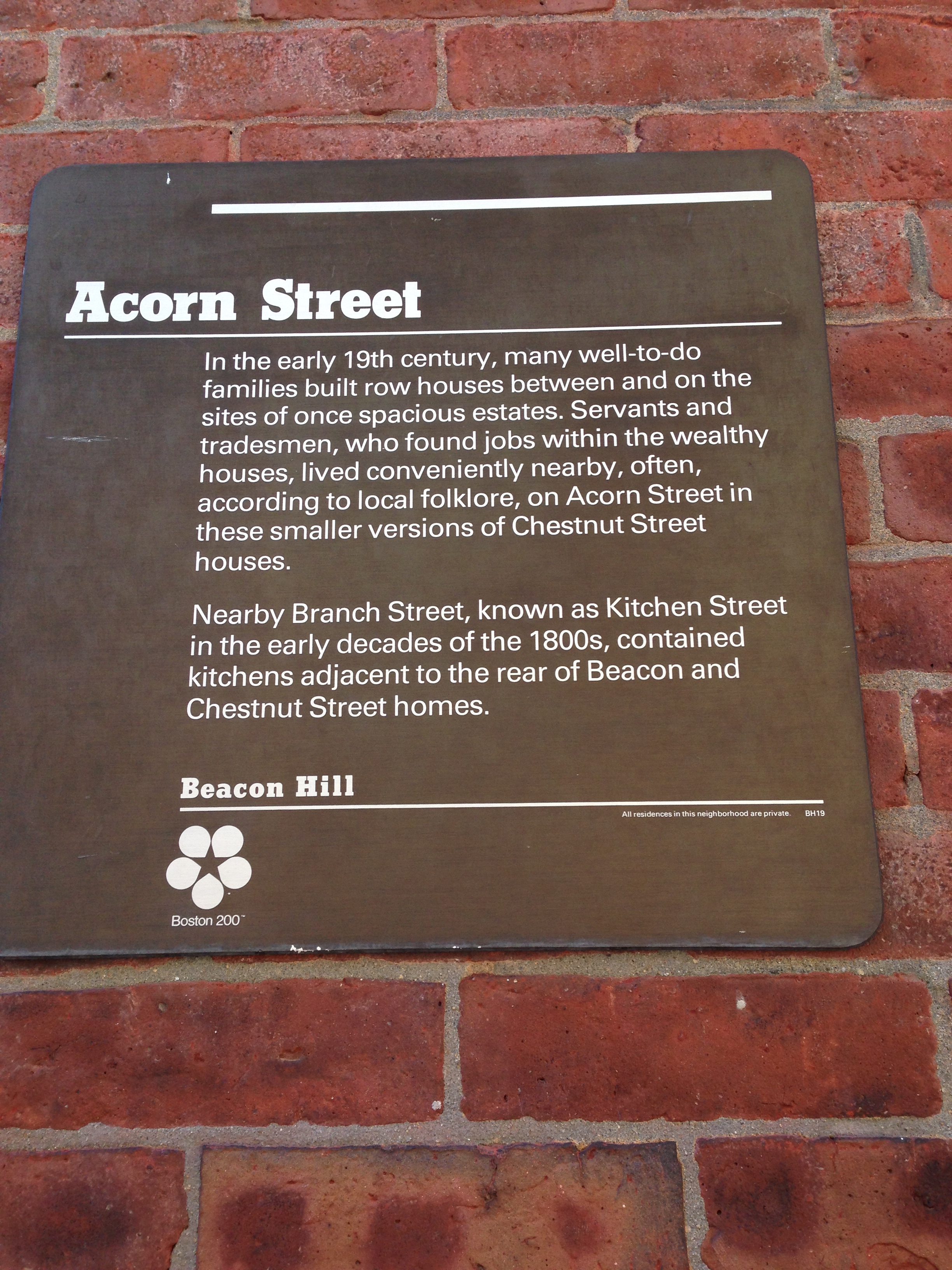

Figure 12: Servants and tradesmen, compared to

Figure 12: Servants and tradesmen, compared to today being populatedby Boston’s wealthiest families,

originally settled Acorn Street.

Another artifact that enhances the historical landscape of Acorn Street and most of the streets in the south slope are the nineteenth century-looking lampposts. As seen in Figure 11, these lampposts are quite different than those usually seen nowadays, but it’s unlikely these were actually built in the nineteenth century. The presence of these artifacts suggests the value wealthy Americans give to historical landscapes, and their preference of living in one. Acorn Street serves as a perfect example of this. This street, which previously was inhabited by servants and tradesmen (Figure 12), is currently inhabited by perhaps the wealthiest families in Boston. This contrast hints that in the past this street must have been undesirable to live due to its narrow nature and the small size of its houses, while today its resemblance of the past attracts the wealthy. As a result, the cobblestones and lampposts present in Acorn Street serve as artifacts to recreate a nineteenth century landscape.

nowadays in most of Boston’s street, while the one on the right is an

example of the antique lampposts seen in Beacon Hill.

The Row Houses

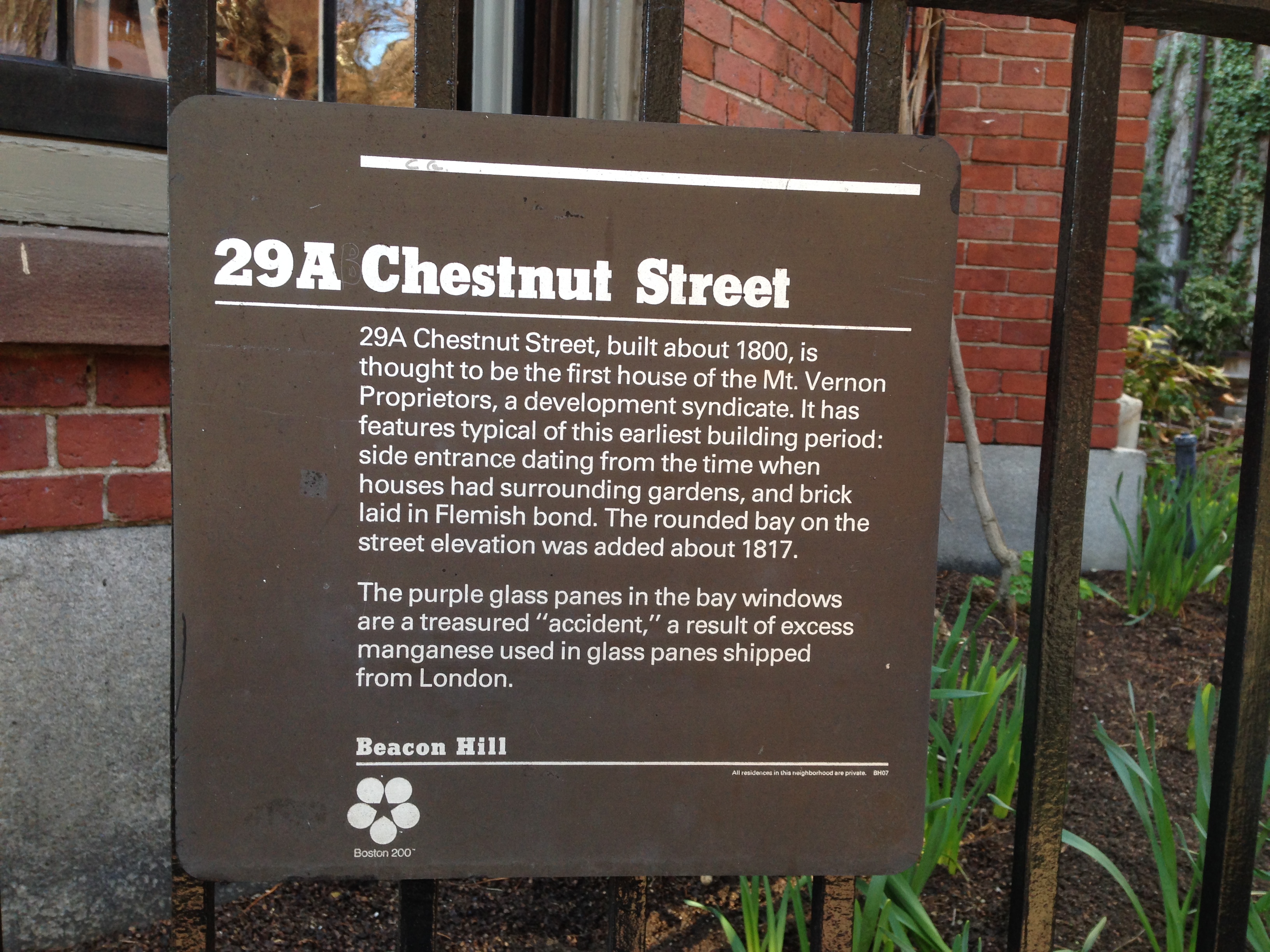

Figure 12: This plate serves as a trace of the previous presence of

Figure 12: This plate serves as a trace of the previous presence of gardens and front yards in Beacon Hill. However, the Puritan culture,

which settled the area in the nineteenth century instilled in it its

tight-knit row house, oriented landscape.

The predominance of row houses in Beacon Hill is not only an artifact of early nineteenth century architecture, but also suggests the presence of a particular demographic composition in the area. Unlike other sites in Boston, subject to diverging demographics in the last two hundred years, the south slope of Beacon Hill has hosted a pretty uniform population profile. As mentioned by Hayden, “there are distinctive design traditions for outdoor spaces associated with different ethnic groups – yards or gardens planted in certain ways identify African American or Portuguese or Chinese or Latino or Italian residents”[1]. Thus, these row houses (Figure 9) characterize the Puritan population present in the area in its settlement in the mid nineteenth century , described by Kenneth Jackson in Crabgrass Frontier as tight knit community with a “hostile view of nature”[4]. Furthermore, we find traces of the previous presence of gardens and front yards in these lots, as seen in Figure 13. This effectively confirms the suppression of open spaces due to the Puritan preference of row houses rather than spacious lots. Hence, compared to other areas in Boston where gardens and front yards are common, in Beacon Hill we see a particular cultural landscape of the Puritan and wealthy Bostonians of this exclusive neighborhood.

The Past as the Trend of the Future

All around Beacon Hill we see places changing: different ethnic groups come along and establish their cultural landscape, single family homes are torn down for apartment buildings, and street patterns change to make way for the railroad, subway, or highways. Here in Beacon Hill, the essence stays the same. Artifacts, traces, and trends are not symbols of change, but rather embody the persistence of history in Boston. Looking at Boston as a whole, there are only a few sites that remain unchanged due to the landfill, urban renewal, suburbanization movements that have shaped the city. Beacon Hill is one of these few sites, and as a result of this, it epitomizes Boston’s historical essence. And nowadays, in the twenty first century, people value this. People value what they can’t have, and since Greek revival row houses with cobblestone-paved streets are scarce, Louisburg Square becomes perhaps the most desirable place to live. This trend is rather ironic. Why, after so many years of urban renewal and modernization movements would people rather live in a place that has been there for the last two hundred years? Unfortunately, epitome districts like this one are not something that can be recreated with an urban planning movement. Instead, we should preserve them and see how, fifty or one hundred years later from now, these become valuable. Since everything else is changing at similar rates, what doesn’t change becomes the outlier. Louisburg Square is one of these outliers: a bubble of history distinct from its renewed and modernized surroundings.

References

[1] Hayden, Dolores The Power of Place Cambridge, MA, 1995.

[2] Warner, Sam B. Mapping Boston, edited by Alex Krieger. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

[3] “Boston's Famous Cobblestones,” Boston City Walks, accessed April 21, 2014, http://www.bostoncitywalks.com/blogs/Boston%20-%20Boston%20Cobblestones.pdf

[4] Jackson, Kenneth. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. Oxford, 1985.