Figure 1. The vendors at Haymarket push their booths forward to avoid the water pooling along the curb. Photograph by author.

Figure 1. The vendors at Haymarket push their booths forward to avoid the water pooling along the curb. Photograph by author. It is a warm day in February when I next visit my site. The recent snowfall piled on the streets and roofs is beginning to melt, and I watch as water flows over the pavement and cobblestones, marking the landscape with small puddles and pools. I see the streaks of salt left on the roads, connecting the many potholes that seem to continually multiply due to the abundant water and constantly changing temperatures of the Boston area. The snow collected on the usually grassy area of the Greenway is covered in footprints, evidence to its continuing use as a public leisure space even throughout the winter months. I walk past a bustling line of Haymarket stalls, each vendor shouting to get the attention of potential customers, and notice how the stalls have been moved forward to avoid the water pooling by the curb. The trees surrounding the Greenway are small and bare, but the warm air surrounding me brings the promise of spring and new life.

Despite being in the center of a large city, surrounded by brick and stone buildings, I realize that I am still experiencing the natural environment. In fact, it seems impossible not to experience it, as I look around me and take in the sights. Nature can be found in the way the wind blows through skyscrapers and across fields, the way that drainpipes and sewers play a role in the hydrological process, the way the pavement settles, breaks, and cracks due to the type of land it has been built on and the weathering processes it undergoes, and in the way that small city trees will bend towards the light in an attempt to acquire the resources they need to prosper. As Spirn writes in her book The Granite Garden, “The city is neither wholly natural nor wholly contrived. It is not “unnatural” but, rather, a transformation of “wild” nature by humankind to serve its own needs.” (Spirn, 4) This interplay between the built environment and natural environment causes cities to continually adapt and grow, and as we learn more about how our actions affect the world we live in, we can eventually hope to reach a sustainable balance between our needs and the rules of the natural world.

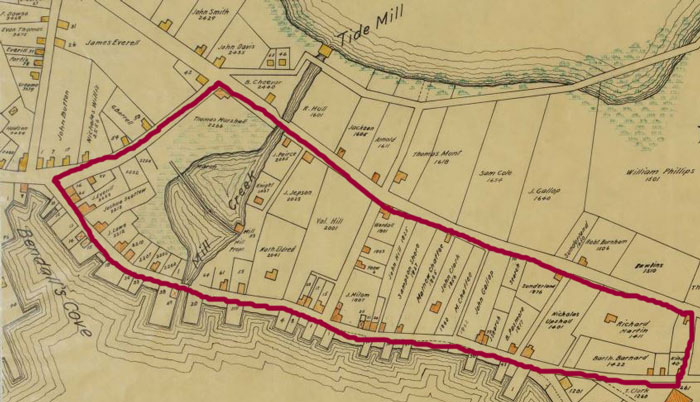

Over the past three and a half centuries, Boston has evolved from wilderness into a thriving metropolis. (Spirn, 13) In order to truly evaluate how the urban landscape has affected and interacted with the natural environment, it is important to consider the historical context of the area. My site has existed almost as it is today since the early days of Boston, yet, as can be seen in the maps below, the area around it has changed drastically. In 1648, water played a huge role in the development of my site, which was enveloped by Mill Pond and Bendall’s Cove and bisected by Mill Creek, which connected the two larger bodies of water. Although none of these bodies of water exist in my landlocked site today, they have left a permanent impact on the city. This can mostly be seen in the place names. For example, the area that was once covered by the Mill Creek is now named Creek Square. Other changes took place over time as well. Wilderness was transformed into houses and businesses, which were then taken down to make room for a highway, which was recently put underground during the Big Dig project. Now that area, called the Greenway, is once again covered in plant life, although the manicured grass and small trees are a far cry from the wilderness that used to inhabit the area.

Figure 2.Map of the Town of Boston in 1648, showing how the North End was separated from mainland Boston by Mill Creek, a tidal creek connecting the Mill Pond to Bendall's Cove. Map from the Samuel Chester Clough research materials toward a topographical history of Boston.(April 1919) Massachusetts Historical Society, http://www.masshist.org/online/massmaps/. Modified by the author.

Figure 2.Map of the Town of Boston in 1648, showing how the North End was separated from mainland Boston by Mill Creek, a tidal creek connecting the Mill Pond to Bendall's Cove. Map from the Samuel Chester Clough research materials toward a topographical history of Boston.(April 1919) Massachusetts Historical Society, http://www.masshist.org/online/massmaps/. Modified by the author.

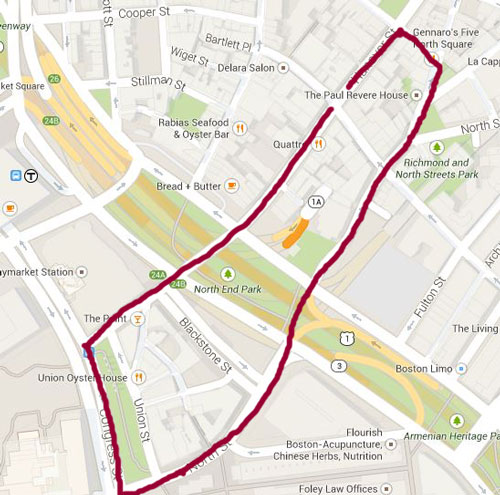

Figure 3. The area that was once bounded on both sides by water is now completely landlocked. Imagery ©2014 Google, Sanborn. Modified by the author.

Figure 3. The area that was once bounded on both sides by water is now completely landlocked. Imagery ©2014 Google, Sanborn. Modified by the author.

Figure 4. Water flows down a pipe and streams down the middle of Marsh Lane to head towards Creek Square. Photograph by author.

Figure 4. Water flows down a pipe and streams down the middle of Marsh Lane to head towards Creek Square. Photograph by author. From my observations, it seems that not only were places named after the hydrological features that used to be part of my site, but also that the flow of water may still have some resemblance to how it was in 1648, when the map in Figure 2 was drawn. The picture below shows some of the water runoff that I noticed during my explorations of my site. The alleyway, Marsh Lane, is leading into Creek Square, and as can be seen in Figure 4, the water is flowing to where Mill Creek used to be. As I continued walking around the area, I observed multiple streams of water leading down to Creek Square and a significant amount of ice covering the ground there. It seems to me that the ground is still slanted as though it were leading to a creek bed, despite the fact that the creek itself no longer exists. This observation is also supported by the lack of development in the area. The winding streets within the block formed by Union Street, North Street, Hanover Street, and Blackstone Street are all made of cobblestone and still arranged in the way they were in the 1800s, leading me to believe that the area hasn’t undergone significant changes since the time when the creek was first filled in.

After analyzing the flow of water down into Creek Square, I realize that the way that water pools in streets can tell you a lot about how that street is used and when it was built. Older, smaller streets, such as Marsh Lane (pictured above in Figure 4) tend to channel water down the middle in order to reduce any damage that the flow of constant runoff could cause to the foundations of the buildings surrounding the street. This of course makes the location of the drainpipe questionable, as it is causing water to purposefully flow down the side of the building to reach the ground. Perhaps a section of pipe that once guided the water all the way to the road without contacting the building itself fell off at some point. In contrast, most modern roadways use a system of raised sidewalks and rounded streets that are elevated in the middle in order to channel water to the drainpipes on the sides of the roads. While this is effective at keeping the water away from the foundations of buildings and off of the main area that cars drive on, it can cause problems for pedestrians as huge puddles form next to crosswalks, as can be seen in the images below. In the picture on the left (taken at the corner of North Street and Union Street), the water becomes an obstacle to pedestrians, forcing them to jump over the puddle, walk around it, or get their feet wet. Although water collection in places like these is an annoyance, this problem is not unusual. The picture on the right, however, is something I don’t see that often. Taken in the North End at the intersection of Richmond Street and Hanover Street, this picture shows a small ramp from the pavement down to street level, eliminating the common puddle problem. Why is it there though? My guess is that it is primarily a convenience for people pushing carts, delivering supplies to the many restaurants and cafes that line the street, and the reduction of puddles is merely a useful side effect. This small ramp also illustrates the interplay between the built environment and the natural environment, and the way they constantly adapt to each other. Water that could originally flow straight into the ground was blocked by the pavement of the street, causing puddles to form, and in response, the city built a ramp to ease the travel of pedestrians.

Figure 5. A puddle of water forms where the sidewalk meets the crosswalk. Photograph by author.

Figure 5. A puddle of water forms where the sidewalk meets the crosswalk. Photograph by author.  Figure 6. A ramp makes it easy for pedestrians to avoid the water. Photograph by author.

Figure 6. A ramp makes it easy for pedestrians to avoid the water. Photograph by author. The effect of water on roads is not limited to how runoff is handled. Considering Boston’s northern geographical location and continental climate, it makes sense that the roads also have to deal with the build-up of snow and ice each winter. The constant freezing and unfreezing of water causes small cracks in the road to open up into large potholes, often leading to patchwork streets as new asphalt is used to cover the gaps. Another noticeable effect of the snowy winters can be seen in the granite curbs lining all the sidewalks. As Spirn mentions in The Granite Garden, “granite curbs became mandatory and now line all of Boston’s streets, a clue to the abundant snowfall -- granite will stand up to the snowplow better than concrete or asphalt.” (Spirn, 16)

Figure 7. A line of bricks that has been forced up by underground structures. Photograph by author.

Figure 7. A line of bricks that has been forced up by underground structures. Photograph by author. Roads and pathways can be affected by means other than water, however. When I first noticed the ridge of bricks sticking up on the sidewalk along North Street, as can be seen in Figure 7, I thought it may have to do with the road settling and causing the whole sidewalk to slant downwards. I knew the area had recently undergone a large amount of construction due to the Big Dig, and reasoned that the soil was still in the process of compacting and settling. After discussions in class though, I realized that the bump in the sidewalk was not due to the settling of land, but due to one of the supports for the highway tunnels constructed during the Big Dig. The interstate highway runs right underneath the Greenway, and since the ridge of bricks is so precisely linear it is reasonable to assume that it was formed due to one of the tunnel’s support beams. In contrast, sometimes the rationale for why bricks or sidewalks are moved the way they are is immediately apparent. This tree in the North End, for example, is obviously pushing the bricks up and apart as it grows too large for the small container it has been placed in.

Figure 8. A tree in the North End pushes brick up with its roots. Photograph by author.

Figure 8. A tree in the North End pushes brick up with its roots. Photograph by author. Street plants like the tree in Figure 8 have to struggle to survive in the harsh living conditions provided for them in cities like Boston. Spirn notes on page 175 of The Granite Garden that, “a city street does not provide the space, nutrients, or water that a tree needs in order to grow. It is an environment hostile to life.” This can be seen in the size of the trees. Despite being planted a long time ago, most street trees stay as small as saplings due to the lack of proper living conditions. Some areas, like the block bounded by Union Street, Hanover Street, North Street, and Blackstone Street have essentially zero plant life, save for occasional patches of moss on the sides of buildings. The North End tries to introduce plant life where it can, like the tree in Figure 8 or by having window boxes with flowers in them, but for the most part the vegetation does not seem to be the healthiest. Although the trees have tried to adapt to their location by angling themselves towards sunlight, sufficient light is still difficult for them to get, due to the narrow streets surrounded by tall buildings. They may also have very little room for their roots to expand, since street trees are often planted in small pits. This can lead to another problem which Spirn describes as “teacup syndrome”: once water gets into a tree pit it cannot drain out due to the compacted soil, which can cause the tree roots to become waterlogged. (Spirn, 178)

Figure 9. Trees can be seen over the top of the brick wall encapsulating Paul Revere's yard. Photograph by author.

Figure 9. Trees can be seen over the top of the brick wall encapsulating Paul Revere's yard. Photograph by author. Given the proper conditions however, trees and plant life can be successful in the city. One example of this is the yard of the Paul Revere House. Although it was closed when I went, I was able to see the tips of many trees peeking out over the top of the brick wall surrounding the yard, as shown in Figure 9. My assumption is that the yard has been preserved along with the house, and can provide enough space and sunlight to the trees for them to be able to survive and prosper. I am concerned for their future though, since part of the Big Dig involved tunneling under that area, which may force a constraint on the growth of the tree roots. Another place where plant life has the opportunity to thrive is on the Greenway. This relatively new area was designed specifically to foster plant life, and while it still has the constraint of being built over a network of interstate highway tunnels, it also has abundant sunlight and a large horizontal area, which should provide the roots with some room to expand. While the Greenway may not be returning the area to the true wilderness of centuries past, the addition of a green space and plant life should have positive effects on the many natural processes of the area surrounding it, such as water drainage and air pollution.

At first glance, cities seem to be isolated from the environment. The world of pavement, parking lots, skyscrapers, and stores can seem completely separate from the land of rivers, streams, forests, and wildlife, but upon further examination it becomes clear that that simply isn’t true. Rain still falls, the wind still blows, and plants still grow, whether you are in an urban metropolis or the middle of a mountain forest. The built environment and natural environment are constantly evolving and changing, reacting to each other as necessary to ensure the survival of both. Nature has proven its tenacity time and time again, persevering in conditions that seem nearly uninhabitable such as on the sides of buildings or in suffocatingly small boxes on the sides of streets. Humans have created a built environment that actively pushes back against nature, and we are beginning to see the effects that will have. As we continue to learn and grow, we should strive to create cities “designed in concert with natural processes, rather than in ignorance of them or in outright opposition” as Spirn writes in her introduction to The Granite Garden. Only then, when we find the balance of our own needs with the rules of the natural world can we ensure ourselves a sustainable future.

Spirn, Anne Whiston. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design. Basic: New York. 1984.