Figure 1. The boundary between Union Street and Marshall Street. Photograph by author.

Figure 1. The boundary between Union Street and Marshall Street. Photograph by author. While standing at the corner of Hanover Street and Congress Street, the first thing I notice is the huge lettering on the brick building across from me. Bell in Hand, A.D. 1795. As I walk past a placard explaining the “Bell’s” journey and naming it the oldest tavern in the US, I notice more taverns proclaiming their history on large signs. Ye olde Union Oyster House, est. 1826. Green Dragon Tavern, “Headquarters of the Revolution”, 1773/1776. These places may be historical artifacts, yet they are still very much alive and a part of the city’s culture. Even as I watch, a large group of uniformed men and their well-dressed spouses and families flows out of the Union Oyster House, presumably coming from a function of some sort that had just ended. I look down a small alleyway next to the restaurant, and note how the street changes from pavement to cobblestone, creating a physical line between the old and the new.

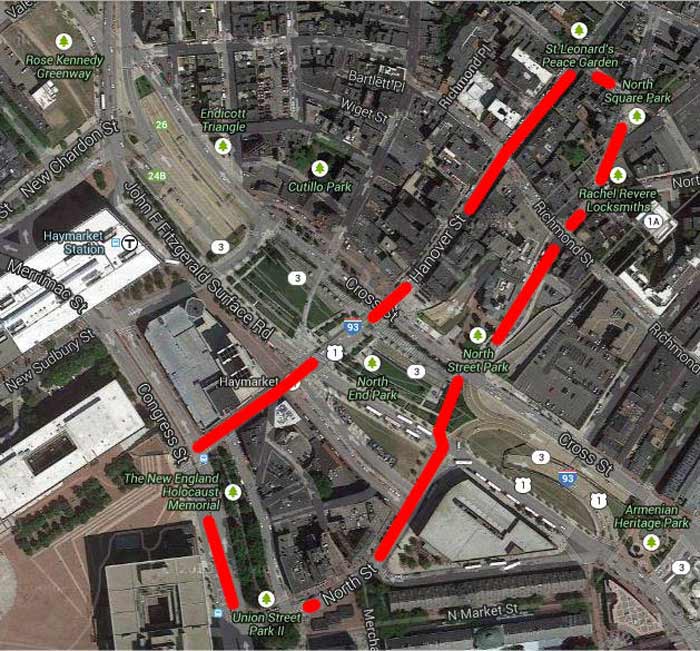

My site was chosen specifically to examine this juxtaposition of the historic and the modern, and see the different ways in which historical sites in Boston have managed to adapt to the 21st century. The area I am studying extends from the New England Holocaust Memorial to the Paul Revere House, and includes Haymarket, the Greenway, the Sumner Tunnel, parts of the North End, and all the Union Street historical taverns, as mentioned previously. A map of the area can be seen below.

Figure 2. Imagery ©2014 Google, Sanborn. Modified by the author.

Figure 2. Imagery ©2014 Google, Sanborn. Modified by the author.

By choosing land on both sides of the Greenway, I am hoping to get a more complete picture of how the Big Dig affected the area and its land use. I am also using the Paul Revere House and the Taverns on Union Street as nodes to give me a frame of reference when looking at historic maps of the area. The buildings’ continued existence brings up many questions, especially considering how much change the area has gone through since their construction. Are they still in their original locations, or have they been moved? If they have been moved, where were they previously located and why were they put this new spot? If they have remained in the same location, how have they persevered through the years, despite the developments surrounding them?

Haymarket is another point of interest for me in this area. Currently, it is a street market open on Fridays and Saturdays that sells produce, fish, and meat at bargain prices. How did it begin though? Was there ever a permanent installation of booths for vendors to use, or has it historically been a true “street market” that could be packed up and hauled away for most of the week? How did it become a significant enough part of Boston to merit its own T station? What happened to it during the years of the Big Dig?

Figure 3. Image of Sumner Tunnel, taken near the Traffic Tunnel Administration Building. Photograph by author.

Figure 3. Image of Sumner Tunnel, taken near the Traffic Tunnel Administration Building. Photograph by author. Although that question remains unanswered for now, I can see clearly how the Big Dig impacted the North End side of my site as I walk northeast across the Greenway. The Sumner Tunnel is a gaping hole underneath a solid wall of brick buildings, making me wonder how exactly its construction was possible. Were new buildings built on top of the tunnel, or was the tunnel dug underneath existing architecture? The location of the Greenway itself is also interesting to me. Why were the highways originally in that location? As Grady Clay mentions in Close-Up, breaks in the grid pattern are often hidden by highways, as shown in his Kansas City example [1]. In the Boston case, were the highways used to cover up a break, or were they simply expanding the flow of traffic to necessary areas? Does the Greenway mark the border of something, like the old city of Boston or the old waterfront? By examining what came before the highways, both the answer to this question and more general questions about why my site is structured and broken up the way it is may become apparent.

Every city is a mixture of old and new, but it seems to me that due to its small size Boston has had to evolve rather than expand. Many old buildings still stand; though some have been repurposed or converted into tourist attractions, others retain their original purpose to this day. The Greenway has undergone its own evolution, though I do not yet know its origins. After investigating the history of my site, the reasons why it evolved the way it did should become more apparent.

[1] Clay, Grady. Close-Up: How to Read the American City. (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1980), 50-52