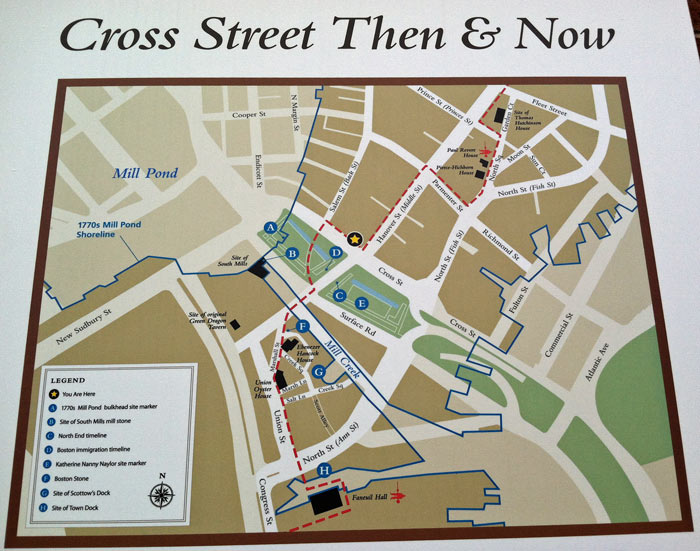

Figure 1. A map of my site that I found on the corner of Cross Street and Hanover Street, where the star is on the map. Historical buildings are silhouetted in black, and the Freedom Trail is represented by the red dashed line. My site boundaries are Union Street, Hanover Street, North Street, and Prince Street. Photograph by author.

Figure 1. A map of my site that I found on the corner of Cross Street and Hanover Street, where the star is on the map. Historical buildings are silhouetted in black, and the Freedom Trail is represented by the red dashed line. My site boundaries are Union Street, Hanover Street, North Street, and Prince Street. Photograph by author.

While walking around my site on a day in late April, I noticed a map posted on the wall of a building at the intersection of Cross Street and Hanover Street. Upon closer inspection, I realized that the map was perfectly centered on my site, and depicted not only the current street layout, but also had an overlay of the 1770s shoreline, including Mill Pond and Mill Creek. It clearly illustrated the history of my site, both through the old shoreline and through the historical buildings that it distinctly labeled. The map encompassed the fact that a city is not made in a day- it is the result of years and years of change and evolution. Traces of the past are all around us, and the history of an area shapes how it can develop, what it can become. The fact that a map like this is posted by my site at all says something very specific about the area I am studying. Although every place is defined by its history, this part of Boston actively celebrates its historical nature. The traces left behind by history are not covered up, but purposefully remembered. As I continued my walk around my site, I paid close attention to the traces of the past, how the history of my site was being remembered, and what kind of future these trends could possibly lead to.

Just as they are silhouetted and labeled in the map, historical buildings on my site are clearly defined and labeled in real life, often by small placards on the front of the building. These plaques help to explain the history of the site, usually including when the building was originally made and what its purpose was. Two examples of this are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Signs found on the Paul Revere House on North Street and the Hancock House on Marshall Street. Both depict not only the history of the building, but also the group that made the sign. The Paul Revere sign explains that it was placed by the Paul Revere Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution group in 1895, while the Ebenezer Hancock House sign explains that it was designated a Boston Landmark by the Bostonian Society and the Boston Landmark Commission. Photographs by author.

Figure 2. Signs found on the Paul Revere House on North Street and the Hancock House on Marshall Street. Both depict not only the history of the building, but also the group that made the sign. The Paul Revere sign explains that it was placed by the Paul Revere Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution group in 1895, while the Ebenezer Hancock House sign explains that it was designated a Boston Landmark by the Bostonian Society and the Boston Landmark Commission. Photographs by author.

While the historical relevance of these sites, as told by the plaques, is fairly interesting, even more information can be gleaned by considering the signs themselves. Who put up the signs and decided that those buildings in particular were worthy of becoming “historical”? What happened in between the time when the building had its original historical use and when it became a tourist attraction, simply a landmark to see?

The Paul Revere House went through each of these stages. As the sign shows, the building was lived in by Paul Revere from 1770 to 1800. After that, it was simply a tenement for many years. On an 1895 Sanborn map it is labelled as a store, presumably with apartments above it. By the 1909 Sanborn map however, the building has been retitled as a “historical site”. This is supported by the plaque in Figure 2, which notes that it was placed by the Paul Revere Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1895. (Although the plaque was placed in the same year that the Sanborn map was drawn, it is possible that the map was published before the change in use of the building was instated.) This shift to a historical site instead of a functional living space is marked by an artifact of the past, the sign pictured above.

Figure 3. Street sign for Blackstone Street that informs observers of the historical creek that used to run below where they are standing. Photograph by author.

Figure 3. Street sign for Blackstone Street that informs observers of the historical creek that used to run below where they are standing. Photograph by author. The signs I found weren’t limited to those explaining historical buildings, however. As can be seen in Figure 3, the street sign for Blackstone Street includes a reference to the hydrological past of the area. Although Mill Creek no longer flows in that location, there is a small artifact, a small sign that remembers its existence. Hayden writes in The Power of Place that, “As a field of wildflowers becomes a shopping mall at the edge of a freeway, that paved-over meadow, restructured as freeway lanes, parking lots, and mall, must still be considered a place, if only to register the importance of loss and explain it has been damaged by careless development.” [1] While the filling in of Mill Creek may not be classified as careless development, it is still important to remember the history of the area and still consider the Mill Creek a place. Spirn further underlines this idea in The Yellowwood and the Forgotten Creek, when she writes, “Once a creek flowed - long before there was anyone to give it a name - coursing down, carving, plunging, pooling, thousands of years before dams harnessed its power, before people buried it in a sewer and built houses on top… No one wonders why the land was free, why water puddles there, why the name of the place is Mill Creek.” [2] It is pure coincidence that both the creek on my site and the creek that Spirn refers to are called Mill Creek, but more important than the name is the fact that the same phenomenon occurs in many places. Water puddles in what is now known as Creek Square in the Union Street block of my site, forming a transient trace of the past whenever it rains or snows.

There is another important street sign not far from Blackstone Street. Marshall Street, known as Marshall’s Lane in 1652, is a perfect example of how the past can shape the present. Thomas Marshall was the original owner of the land at the corner of Hanover Street and Union Street in the 1630s, and today Marshall Street runs across that very same land.

Figure 4. Building bounded by Hanover Street, Marshall Street, and Blackstone Street. Notice the old signs painted onto the walls advertising Bostonian Cigars for ten cents. On the right is a close-up of the Marshall Street sign, which recalls the site’s origins as land owned by the Marshall family. Photographs by author.

Figure 4. Building bounded by Hanover Street, Marshall Street, and Blackstone Street. Notice the old signs painted onto the walls advertising Bostonian Cigars for ten cents. On the right is a close-up of the Marshall Street sign, which recalls the site’s origins as land owned by the Marshall family. Photographs by author.

On the same building as the Marshall Street sign is a huge painted advertisement, worn away by years of harsh weathering. It promoted Bostonian Cigars, available at ten cents each. This advertisement is a trace left behind by the years when that building was a cigar factory and store, as it was labeled in a 1909 Sanborn map. Factories were plentiful in the North End and Union Street area during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, right when many immigrants were living in that part of the city. These factories provided low wage jobs, many of which only immigrants would be willing to take on. The remnants of the cigar factory sign harken back to this era, and help paint a picture of what life was like at that time, both in terms of what sorts of jobs were available, the public opinion of smoking, and also the price of goods. Cigar factories and stores are very rare today, due to our increased medical knowledge of the risks smoking poses, and the prices of goods are far greater than the advertised ten cents, showing how inflation has changed the way the economy functions. The fact that this building is still standing and that the advertisement has not been washed off or painted over reinforce the idea that this section of Boston is proud of its historical roots, and will actually go out of its way to preserve historical sites.

Looking at the Union Street block from another angle, the side facing Blackstone Street, it becomes clear that the cigar factory was not the only industrial building in the area. The faded lettering on the building to the right in Figure 5 advertises W.P.B. Brooks & Co., a company established in 1836 that appeared to sell furniture and carpets. From old Sanborn maps it is clear that furniture stores and factories were very prevalent in the North End and Union Street blocks, and it is likely that immigrants formed the majority of the workforce.

Figure 5. Buildings on Blackstone Street. To the left is Durty Nelly’s Olde Irish Pub, and to the right is W.P.B. Brooks & Co. Furniture and Carpets. Both evoke history in a unique way- the furniture store sign appears to be the original, painted in 1836 when the store was established, while Durty Nelly’s is clearly a more recent addition, though it taps into the fact that Irish immigrants were extremely prevalent in the area in the 19th century. Photograph by author.

Figure 5. Buildings on Blackstone Street. To the left is Durty Nelly’s Olde Irish Pub, and to the right is W.P.B. Brooks & Co. Furniture and Carpets. Both evoke history in a unique way- the furniture store sign appears to be the original, painted in 1836 when the store was established, while Durty Nelly’s is clearly a more recent addition, though it taps into the fact that Irish immigrants were extremely prevalent in the area in the 19th century. Photograph by author.

To the left of the furniture store is Durty Nelly’s Olde Irish Pub. The sign is much newer, and it is possible that the restaurant has been rebranded from Pete’s Pub, whose sign is painted onto the side of the building. It is unclear if there are two separate restaurants or simply two iterations of the same restaurant, but either way the signs tell a story. The Pete’s Pub sign is painted directly onto the wall, something not commonly done today, and it appears to be slightly weathered, though nowhere near as weathered as the furniture sign or cigar factory sign, meaning that it may have been a precursor to Durty Nelly’s. The Durty Nelly’s sign is clearly a more recent addition, yet it uses a font that attempts to seem like old handwriting, and uses the Old English “Olde” in its title, attempting to evoke a feeling of nostalgia or history. It also references the huge amount of Irish immigrants that flocked to the area in the 19th century to escape the Potato famine in Ireland. Whether or not the restaurant was actually started by Irish immigrants, it is still a trace of the Irish history of the area, and in general shows the how historic sites are celebrated and a source of pride for the community.

Figure 6. Italian restaurants are abundant in the North End. Pellino’s Ristorante and Artu Rosticceria & Trattoria are only a few of the many choices lining the streets. Photograph by author.

Figure 6. Italian restaurants are abundant in the North End. Pellino’s Ristorante and Artu Rosticceria & Trattoria are only a few of the many choices lining the streets. Photograph by author.

Figure 7. The Holocaust Memorial, found between Union Street and Congress Street, is a trace left behind by the Jewish immigrant population that lived in the area during the 20th century. Photograph by author.

Figure 7. The Holocaust Memorial, found between Union Street and Congress Street, is a trace left behind by the Jewish immigrant population that lived in the area during the 20th century. Photograph by author.Restaurants can be a great way to tell the ethnic composition and history of a site. While Durty Nelly’s over in the Union Street block is a trace left by the Irish immigrants, the North End is mostly characterized by the traces left behind by Italian immigrants. Italian restaurants line the streets, with names such as “Pellino’s Ristorante”, “Artu: Rosticceria & Trattoria”, and “Villa Francesca”. There is still a large Italian population in the North End today, causing the area to earn the nickname “Little Italy”.

At the same time as the Italians were immigrating to the North End there was also a large influx of Jewish immigrants. Although there are not many signs left behind of their time on my site, there is one very distinctive landmark that can be explained by the Jewish presence in the area. Between Union Street and Congress Street on the southern tip of my site sits Boston’s Holocaust Memorial, a pathway that leads visitors through tall glass structures that bear the numbers of the many people who died in the Holocaust. Initially it seems like a rather strange place to have a Holocaust Memorial. There is no synagogue nearby, no other Jewish landmarks or communities. By looking into the past however, the location of the memorial makes more sense. It is a trace of a strong immigrant population that used to fill the area. Even though the Jewish population has moved to other areas of the city, they have left a mark on the site through the placement of the Holocaust Memorial.

Figure 8. Juxtaposition of the old and the new: an 18th century tavern on Union Street can be found next to a sign advertising office space for rent. Photography by author.

Figure 8. Juxtaposition of the old and the new: an 18th century tavern on Union Street can be found next to a sign advertising office space for rent. Photography by author.

My site is characterized by an abundance of historical buildings that coexist with the active, modern city around them. Boston doesn’t try to hide or cover up its origins. Instead, it chooses to celebrate them and emphasize just how much history is contained in such a small area. As can be seen in the picture above, taverns dating back to the 18th century can be found directly next to signs advertising office space for rent. While my site is historical, that does not mean that it is stagnant. The trend is for old buildings to be preserved, but in a way that allows new life to flourish and grow around them.

This can also be seen on my site in the trend towards tourism that arose in the past century, as the area moved away from its industrial manufacturing roots. The Freedom Trail, a path that leads tourists past many famous historical sites in Boston, traces an outline of my site, as can be seen in Figure 1. It stops by sites such as the Paul Revere House and the Hancock House, and is an example of how the city chooses to highlight its history. The old buildings are still able to be useful to the community and provide a net benefit, since they draw tourists to the area who can then patronize the stores and restaurants. What used to be a more residential and commercial area has slowly been shifting to become even more commercialized and tourist friendly.

The area’s history as a residential area and its current role as a tourist hot spot can be seen below in Figure 9. There are many layers to my site, and they are embodied in the picture below. At the front right is the Paul Revere House, a short building with side panels and stained glass windows. This older house contrasts sharply with the tall buildings around it. Immediately adjacent to the Paul Revere House is what used to be a tenement house with stores on the ground floor. Behind the House can be seen those tenement buildings that have no direct street access, which used to provide cheap housing for the many immigrant families that had come to the area. Presumably many of these buildings are still used as apartments today. This mix of functionality next to tourist attractions embodies the character of my site.

Figure 9. The layers of my site are made obvious when looking at the area surrounding the Paul Revere House. Photograph by author.

Figure 9. The layers of my site are made obvious when looking at the area surrounding the Paul Revere House. Photograph by author.

My site is heavily defined by its historical origins. The trend of preserving historical buildings and locations suggests the amount of respect people have for the artifacts and traces left behind by history. My area of Boston chooses to celebrate its past, and creates a space where historical buildings and modern people can coexist easily. This juxtaposition of the old and new was what drew me to my site in the first place, and understanding how it all works together leads me to believe that the area will continue to be a mix of history and modernity for years to come. The recent trend towards tourism promotes both sides of the equation: it requires historical sites to be preserved while it also provides business for local stores and restaurants. Boston is a very historical city, and in my site this history is truly the driving force behind the way in which the area exists today.

Notes

1. Dolores Hayden, The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History (Cambridge Massachusetts: MIT Press), 18.

2. Anne Spirn, “The Yellowwood and the Forgotten Creek,” in The Language of Landscape (Yale University Press).

Bibliography

Hayden, Dolores. The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History. Cambridge Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Spirn, Anne. “The Yellowwood and the Forgotten Creek,” in The Language of Landscape. Yale University Press.