"Old downtown" is one way to describe the area encompassing the Blackstone Block and Fanueil Hall Marketplace; its age is visible in the wear and tear on those distinctive red bricks, in the uneven cobblestone paving, in the architecture and in the plaques bolted onto most of the buildings declaring the area a national historical park.

That look--rusted pipes, weathered walls, and the strange juxtapositions of modern additions to centuries old structures--has been molded and shaped by the ongoing natural processes that are present in every city. Visible but subtle, the effects of earth, water, wind, and life have left their marks on this bustling area of downtown Boston.

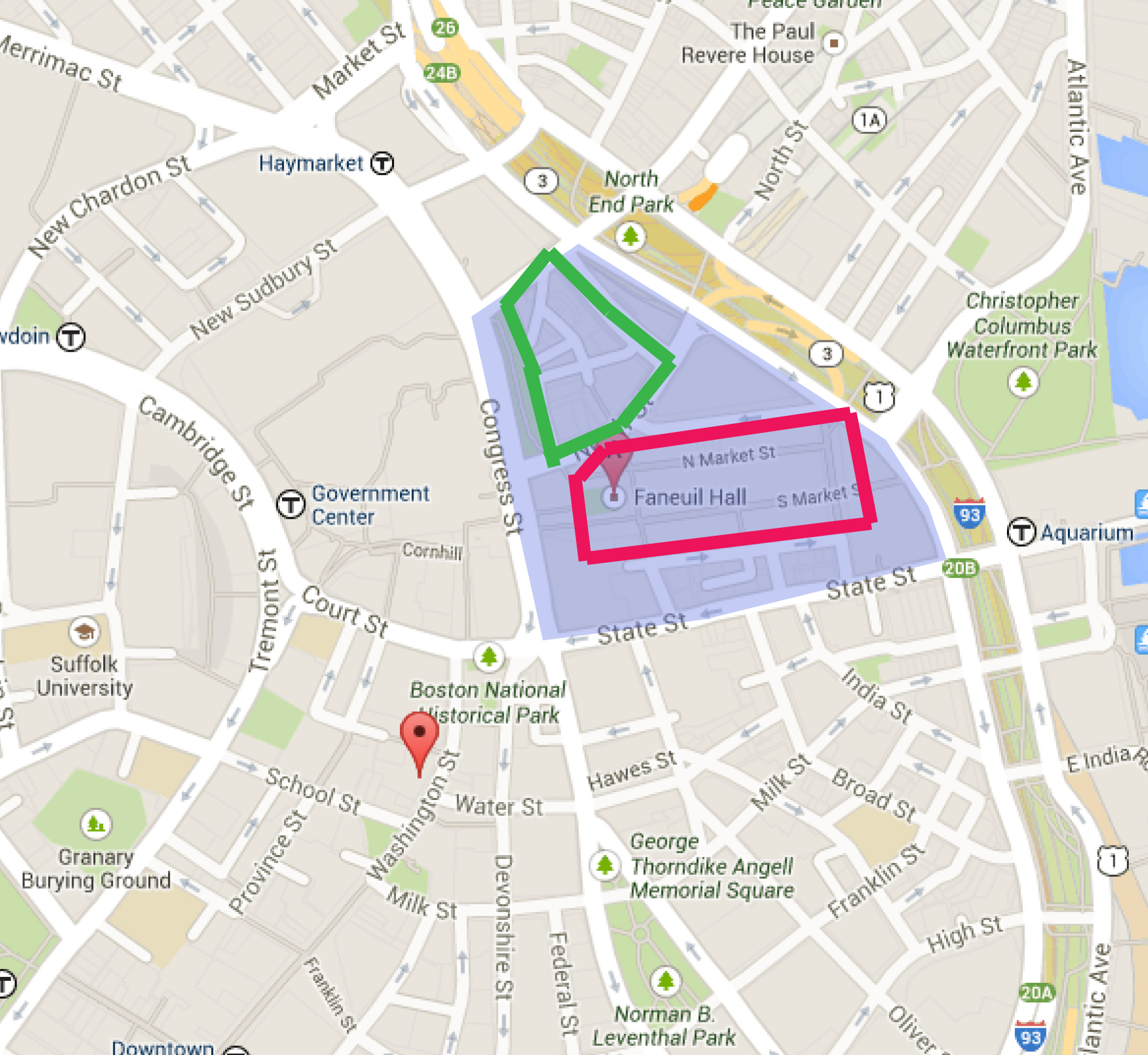

Figure 1: Street view map of site, highlighted in purple. Blackstone Block is outlined in green and the Faneuil Hall Marketplace is outlined in red. (Google Maps, 2014) Figure 2: An 1867 downtown Boston street map (ProQuest, LLC., 2001) overlaid on the image in Figure 1.The original shoreline closest to the site is outlined in red.Faneuil Hall Marketplace and the rest of this site lies along the "Walk-to-the-Sea"--an "axis" of Boston that consists of the walking route from the state capitol up on Beacon Hill, through the Government Center and the Marketplace, and ending (appropriately) at the harbor along Long Wharf. The shoreline, however, used to be much closer (see Figure 2), as the land was filled to expand the port during the 20th century.

This extension of the coastline is where one can begin to elaborate on the effects of nature and natural processes on this site. The Atlantic Sea has always been a dominant consideration in settlement patterns from Boston's beginnings; the proximity to the water had offered a potential harbor and hub of trade and commerce to the first residents. But as Boston's population grew (and new methods of transporting goods emerged), the land had to be expanded as well--to the point where today, the water is several hundred meters' distance from Quincy Market. As Alex Krieger puts it in his book, Mapping Boston, "The use of the waterfront, access to it, and its design have been fundamental concerns since the founding of the city. Like the tide itself, however, the immediacy of the water's edge has ebbed and flowed in the consciousness of Bostonians. (p150)"

Despite the fact that the sea has literally become a more distant presence in the Faneuil Hall/Blackstone Block area, it has definitely left its mark. And ironically, it is that new distance--made possible by landfill--that has caused some of the more visible traces of natural processes on the structures and the land. The older buildings in this site, especially the ones nearest the coastline (such as the Quincy/North/South Markets and the buildings along Blackstone St.), boast cracks that run vertically along their facades from settling landfill (see Figure 3). As Anne Spirn, author of The Granite Garden, notes, "In coastal cities like Boston, half the downtown may have been constructed on filled land, whose stability depends on its content and the length of time it has been in place. Garbage, rubble, and the wood of old wharves and sunken boats decompose at different rates and may cause subsidence for many years."

Figure 3: Visible differences in the color and age of bricks in blackstone block buildings; border between the two sections lightly outlined in magenta.Evidence of the use of filled land is not only visible in the shifting walls of buildings, but also in the precautions taken against the consequences of doing such. Spirn also brings up the problem of flooding: "...filled land is not without problems. Much of the land is quite low and susceptible to flooding. Extensive areas have a saturated soil whose fluctuating water level can damage building foundations". And indeed, as even the older Blackstone Block buildings were built upon filled land, some of them have doorways that are elevated off the ground (Figure 4), with a layer of stone and waterproof lining below to protect the weary foundations from waters.

Figure 4: A layer of stone lined with protective waterproof material can be seen under elevated doorways. Also visible--another example of visibly different ages of brick in the building facades.Furthermore, there are a multitude of sewer grates--sometimes up to three in a 30-foot square area--that dot the cobblestone streets to ensure that water does not pool and subsist in the streets, where it can seep underneath the buildings.

In fact, within the boundaries of the site, nowhere is the landfill's subsidence more noticeable than in Blackstone Block. The Block, consisting of the area bounded by Salt Lane, Marshall St., Marsh Lane, Scott Alley, and Creek Square, is an area of great historic and commercial value to the city. The Union Oyster House and other establishments and landmarks from the Colonial Era can be found within the block--along with ample evidence of the block's original location atop a salt marsh. Again, Figures 3 and 4 depict two of many examples of "replaced" areas of brick in the facades of the Blackstone buildings, likely necessitated by settling foundations; furthermore, the streets have a noticeable downward slope towards the shoreline, which could be accounted for by the fact that the closer a portion of landfill is to the water, the faster it sinks, creating a slight incline toward the coast. The uneven surfaces of the streets are yet another manifestation of this subsidence; Figure 5 is a great example of the peculiar ways in which settling soil has shaped the streets.

Figure 5: The street forms a small mound under a manhole as the soil around it settles.An interesting phenomenon relating to the age of the Blackstone Block and the differences in structure of its older brick buildings compared to the newer buildings surrounding them is the consequent differences in wind patterns. Any passing pedestrian can observe that the historical buildings are shorter, squatter, and more irregularly shaped than the more recent developments, for fairly obvious reasons--advances in building technology, greater access to resources, changes in aesthetic, etc. This anomaly in the height and design of an entire block could be considered a predictive feature of historic sites in urban environments--if you're looking for the original settlement, look for areas of collectively shorter, stranger buildings. What more, this difference in height and design appears to create a different wind environment within the block as well--the curving, narrow streets, interconnected buildings, and relative lack of taller, eddy-creating structures meant that, during a recent site visit, the fairly heavy gusts of wind that could be felt walking down Congress St. seemed to die down almost entirely upon entering the narrow alleys of the Block.

Another instance of the variety of wind patterns possible within a city's complex architecture is in the Marketplace. Consider the orientation and structure of Quincy Market, while keeping in mind that Quincy Market was originally located at the shorefront. The elongated market buildings were likely purposely built to "point" toward the coast, and the wide walkways between the three buildings intentionally oriented parallel to incoming sea breezes and beautiful views of the harbor and the ocean. Quincy was not designed to be an over-crowded, stuffy market with little room to breathe--the sea brought in cool gusts of wind that fed through the lengths of the North and South Market Streets, and a day out shopping could be wrapped up with a pleasant stroll down to the shore. This is one of many instances where it can be seen that Boston began and continued as a city of people who thought of the whole, rather than the immediate, while taking natural processes like coastal winds and weather into consideration.

Figure 6: A shock of green between the red brick, grey stone, and dull asphalt of Blackstone Block. (Google Maps/Sanborn Maps, 2014)Some natural processes, however, are initiated by man. The Google Maps view of this site reveals an almost comical tuft of green in the center of the block (Figure 6); upon closer examination, this patch of green consists of two trees, looking to be fairly young, growing in a corner of a backlot of one of the buildings. A small border of bricks surrounds their trunks, but given their size, it is likely that their roots extend far below the brickwork. These two beings--stranded in a sea of pavement and parking lots--are a wonderful example of the hardiness of city trees. Despite the fact that most of their presence is a result of preplanning and human intention, city trees are still forces of life, and undergo as well as affect natural processes within the urban ecosystem.

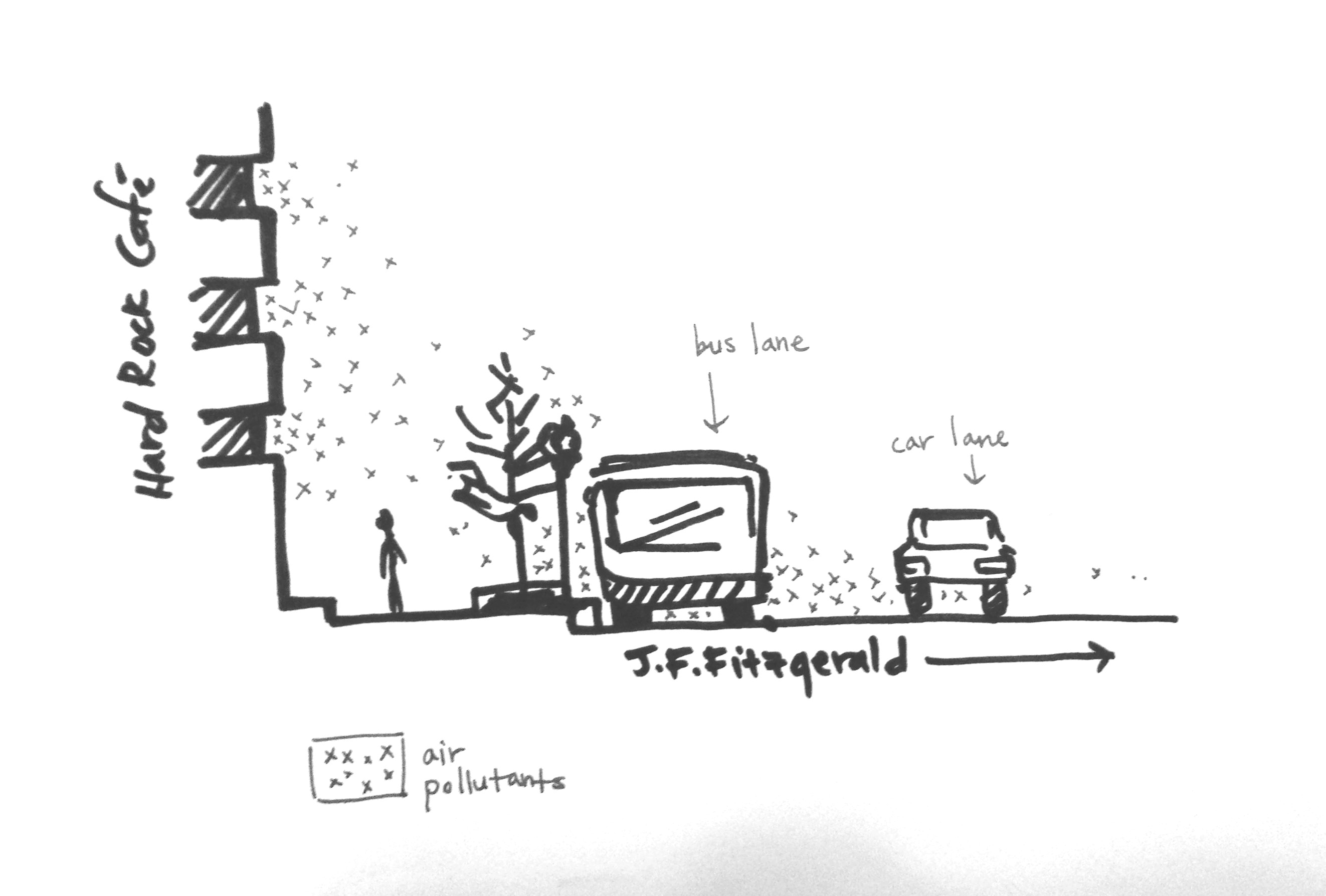

Not all of them are as fortunate as the Blackstone Block trees, however. Lining John F. Fitzgerald Surface Rd. is a row of diminutive trees; current visitors to the site can see them thin, white, and bare in the midst of the Boston winter. They line up in between a major highway and one of the three sides of the parking garage that sits over Hard Rock Cafe (see Figure 7), in little planters that are raised about half a foot off the rest of the sidewalk.

Figure 7: An illustration of the hostile conditions for the trees along J.F. Fitzgerald Surface Rd.They are in a location where they absolutely marinate in air pollution. Spirn elaborates: "A city street does not provide the space, nutrients, or water that a tree needs in order to grow. It is an environment hostile to life (p175)". To add insult to injury, there is a bus lane along that sidewalk, where public transport and private tour buses alike will sit and idle for 10-15 minutes at a time, spewing exhaust fumes. Furthermore, given the tiny space they've been allocated, it's very probable that they are exhibit the "false juvenile form" due to hostile conditions that Spirn brings up as a phenomenon in city trees: "Long, leggy branches on a young tree reflect fast growth nurtured by an ideal combination of water, sun, and nutrients, a distinctive form typical of the newly planted, nursery-bred specimen. Under normal conditions, the tree fills out within a few years of transplanting, but street trees are often frozen in this juvenile form...In a hostile environment [like Charles Street] these trees persist as dwarves until they die, when they are replaced like the petunias set out each spring in flower pots hanging from nearby lampposts (p177)".

The natural process here is one of nature being affected, rather than causing effect--unfortunately, in a negative fashion. These trees will likely never grow much larger than they are now, and may have to be replaced in several years.

On the other hand, within the boundaries of the site, there is yet another drastically different example of city trees and their livelihood--the honey locusts that line the avenues in between the Quincy Market buildings. These are impressively tall trees, towering over the market's renowned central dome. And yet--humorously--they appear to be perched in miniscule concrete planters of no more than 6'x6', which is far too small of a space to account for their size; as Spirn notes: "A four- to six-foot square planting hole will support a mature tree of only twenty to twenty-five feet in height (p193)". Yet, as Figure 8 shows, these honey locusts are well over 40 feet tall.

Figure 8: The well-matured honey locusts in Quincy Market. Figure 9: The roots and concrete planter of one of the honey locusts in Quincy Market.Looking closely at the base of the trees (Figure 9) reveals that indeed, the roots appear to travel much deeper into soil than the planters could possibly provide and to stretch underneath the brick-paved walkways themselves, which indicates that the planters were likely placed around the preexisting tree. Given that the Marketplace has been seen by Boston as a center of lively pedestrian activity since its construction, and that Boston has always been a city oriented toward public services and civic improvements, it makes sense that the idea of placing trees along the avenues had already been implemented before any more recent additions--including the planters--had been made. In this instance, the endurance of these trees to grow through decades of renovation, repaving, and human traffic (note the cigarette butts scattered amongst the roots in Figure 9) is the natural process at work.

Figure 10: The weathering of brick along the sidewalk behind North Market; most prominent in the area above the magenta line.Weathering, regardless of what it is caused by, is a natural process as well. There are examples of weathering everywhere--but especially frequent are the instances along the sidewalks and streets. Here, in Figure 10, the bricks along the edge of the sidewalk are in the process of disintegration--years of wear from cars, trucks, people, and harsh weather accumulate along the boundary of the sidewalk and the street, and the broken and uneven edge of the sidewalk is visual evidence of such a process. One can also look down any of the asphalt-paved streets in the site and see cracks and imperfections where traffic is heavy--examples of weathering that are oft dismissed by the casual observer because of how common they are--yet these cracks are part of a powerful natural process nonetheless.

The city is not, as many people imagine, a steel-clad, man-made castle isolated from nature. It is at once a part of the preexisting natural environment and a distinct natural environment itself; the city undeniably affects the landscape around and underneath it in significant ways, but in return, it is subject to the equally (if not more) great forces of wind, water, earth, and life. Given that this site is in one of the oldest areas of Boston--and, accordingly, has stored up layers and layer of history in its land and its structures--the presence of nature and its processes has become, unsurprisingly, quite visible and tightly connected to the current state of the site's streets, buildings, and landmarks.

Works CitedGoogle Maps. Boston, MA. 2014. Map. n.p. Web. 7 Mar 2014.

Google Maps/Sanborn Maps. Boston, MA. 2014. Map. n.p. Web. 7 Mar 2014.

Krieger, Alex, and David Cobb. Mapping Boston. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1999. Print.

ProQuest, LLC.. Digital Sanborn Maps. 2001. Map. n.p. Web. 7 Mar 2014.

Spirn, Anne. The Granite Garden. Basic Books, 1985. Print.