It was a pleasant 54 degrees when I walked into the sunlight from the darkness of the Government Center station steps, and I had just a couple of seconds to pause and enjoy the fantastic weather before I was knocked forward by a large group of chatty young adults around my own age. Shoppers, I presumed; and indeed, they headed off toward the stairs leading down to the Faneuil Hall Marketplace.

As I approached the Marketplace, I could hear the steady bass beat of a hip hop song, muffled by the bodies of the crowd surrounding the street performers who were dancing to said song. This wasn't the first time I'd seen performances--both musical and otherwise--take place in the open space in front of Fanueil Hall, and it's not unreasonable to guess that this space has been used as a public arena since the initial construction of the Hall. A trend, as it could be described, reflecting the initial intention of the Marketplace as an attraction and center of activity for the rest of the city. The Marketplace, after all, was planned from the outset to be used for commerce--both the design of the building complex and the ground upon which the buildings were built (filled land) point back to the same mindful city planning that developed the Beacon Hill area and facilitated the filling of Mill Pond. In fact, many of the major changes surrounding the site that are visible in maps of Boston proper from the 17th and early 18th centuries are related to the development of the area using filled land. Moreover, numerous traces of these past changes are present in the site today.

The relatively sharp slope of the area between State and Congress St. is just one example; the use of landfill creating a "dip" in the larger landscape. Even the public seating and shade provided along the two streets reflect their slopes (Figure 1); an otherwise symmetric facade of one of the office buildings along Congress St. (Figure 2) is unbalanced by an extra step on the right, also indicative of the downhill slant of the street.

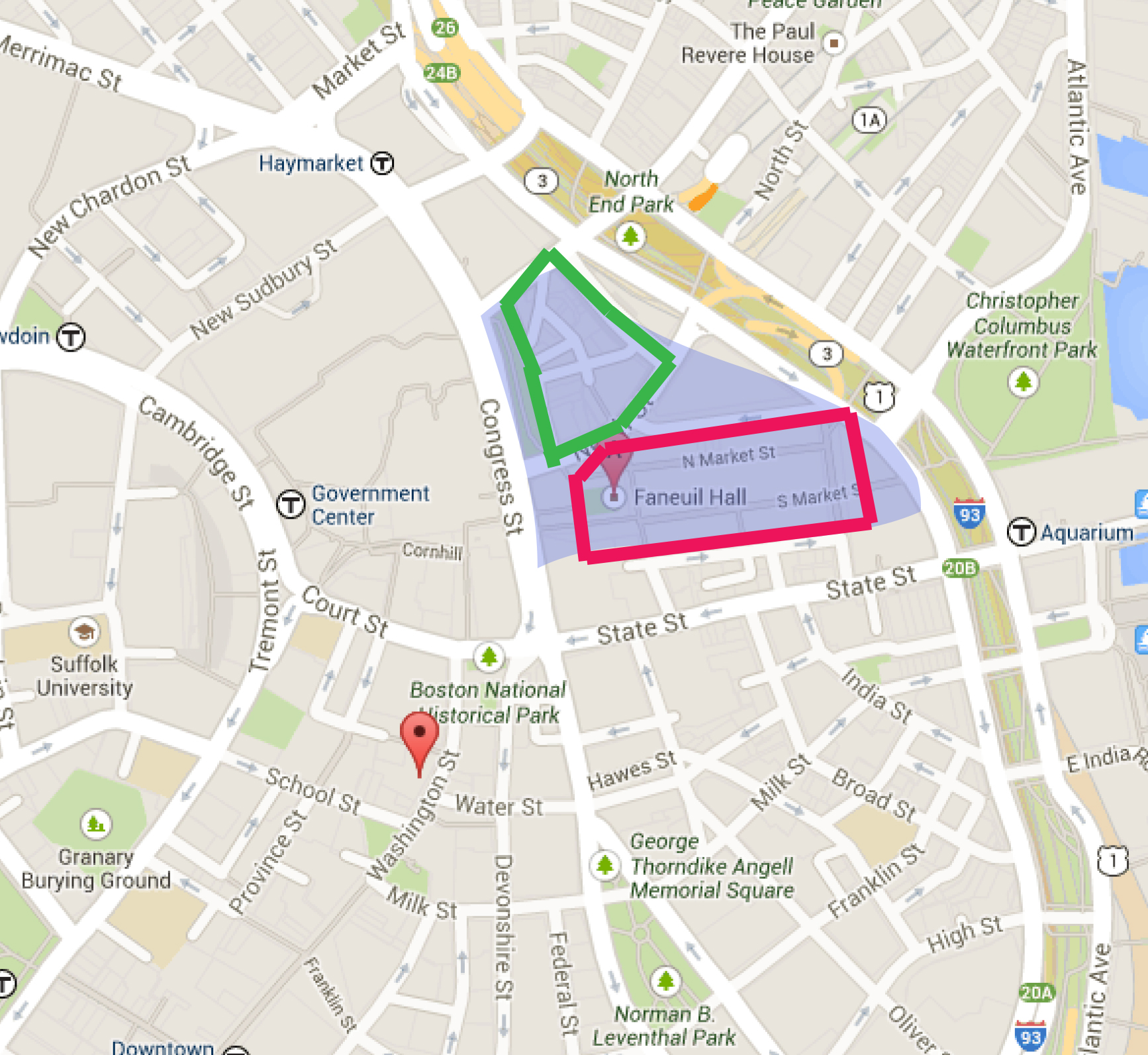

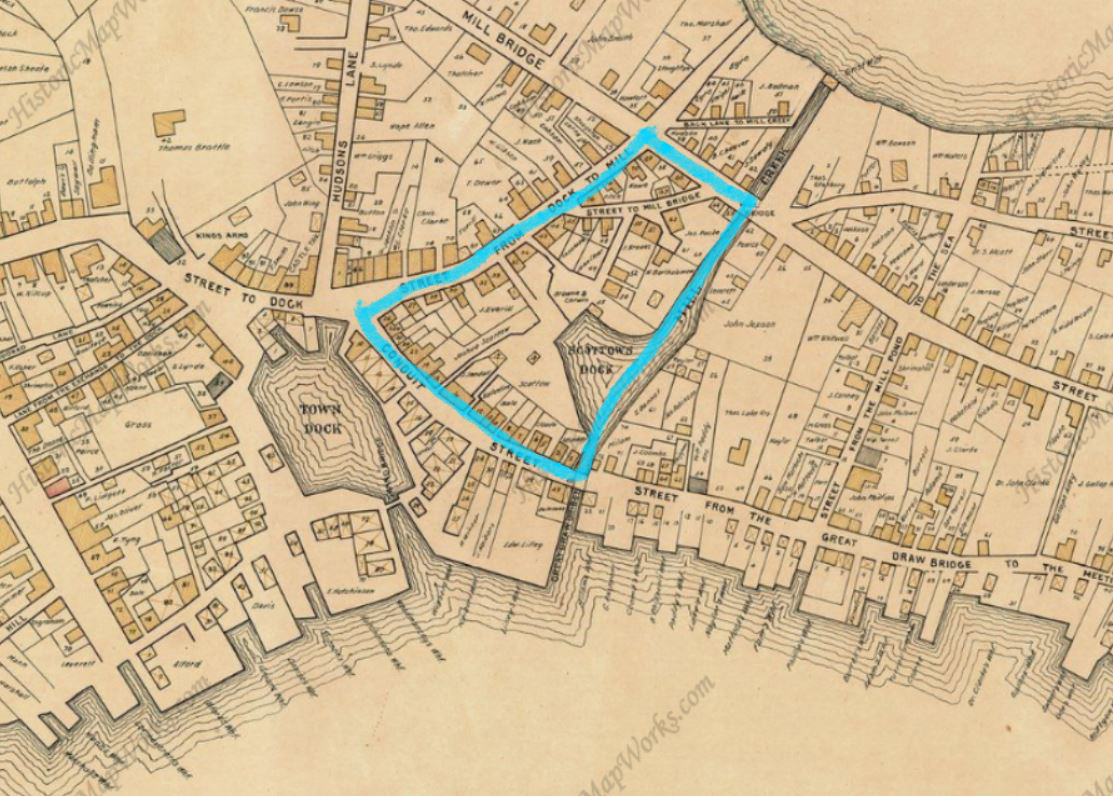

Figure 1: stepped shade Figure 2: broken symmetryObserving a map of what this site looked like in 1676 (Figure 3) reveals the considerable portion of the site that was once underwater. A common trend visible in present day is in the naming of streets and structures after the aquatic bodies formerly found in/near the site; Creek Square's street sign marks where there used to be a creek and a marsh in the Blackstone Block, and the parking garage behind the North Market building boasts the name "Dock Square Parking Garage". This title contains three layers of the naming trend; "Dock Square Parking Garage" is named after Dock Square, which was an actual location and can be found in maps created before the extension (i.e., Figure 6, a portion of a 1988 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map of the Marketplace; Dock Square can be seen in the upper right hand corner of the image) and widening of Congress St., during which the square was eliminated. The square, then, was named after and marked where there used to be an actual Town Dock in the site area, also visible in the 1676 map.

Figure 3: A 1920 depiction of 1676 Boston. Blackstone Block is outlined in blue for reference. Source: Samuel Chester Clough. Boston 1676 [map]. 1920. "Boston 1676 Created 1920c MHS Digital Image 3850." Massachusetts Historical Society. Figure 4: the street sign for Creek Square. Figure 5: Dock Square Parking Garage Figure 6: Dock Square was still extant at the time this map was created. Source: Sanborn Map Company. Boston Volume 1N, 1988 [map]. 1867. Sanborn Map Company.Other name-related traces of the original shoreline and of the site's long history of being a center for commerce can be seen in some of the structures just off the site boundaries--the street that runs starting from the Marketplace along Long Wharf is entitled "Atlantic St." (which, as can be seen in maps created after the creation of Long Wharf, has always been called such), and the massive brick building across the Fitzgerald Expressway from North Market bears the name "Mercantile Mall" (Figure 7). A real estate advertisement perches on the top of the Mall's facade; this, in combination with the bricked-up windows and the rather worn-down air of the building, points back to the conversion of many of this vicinity's structures into warehouse storage during the mid 1900s due to the economic decline of the area.

Figure 7: Mercantile Mall.The North Market building, too, has been left with vestiges of this warehouse conversion. While the upper floors of both South and North Market buildings are now office space, the back face of North Market is still adorned with a steel pulley system, railings, and landings that appear to have been used to hoist storage items into the upper floors (Figures 8 and 9).

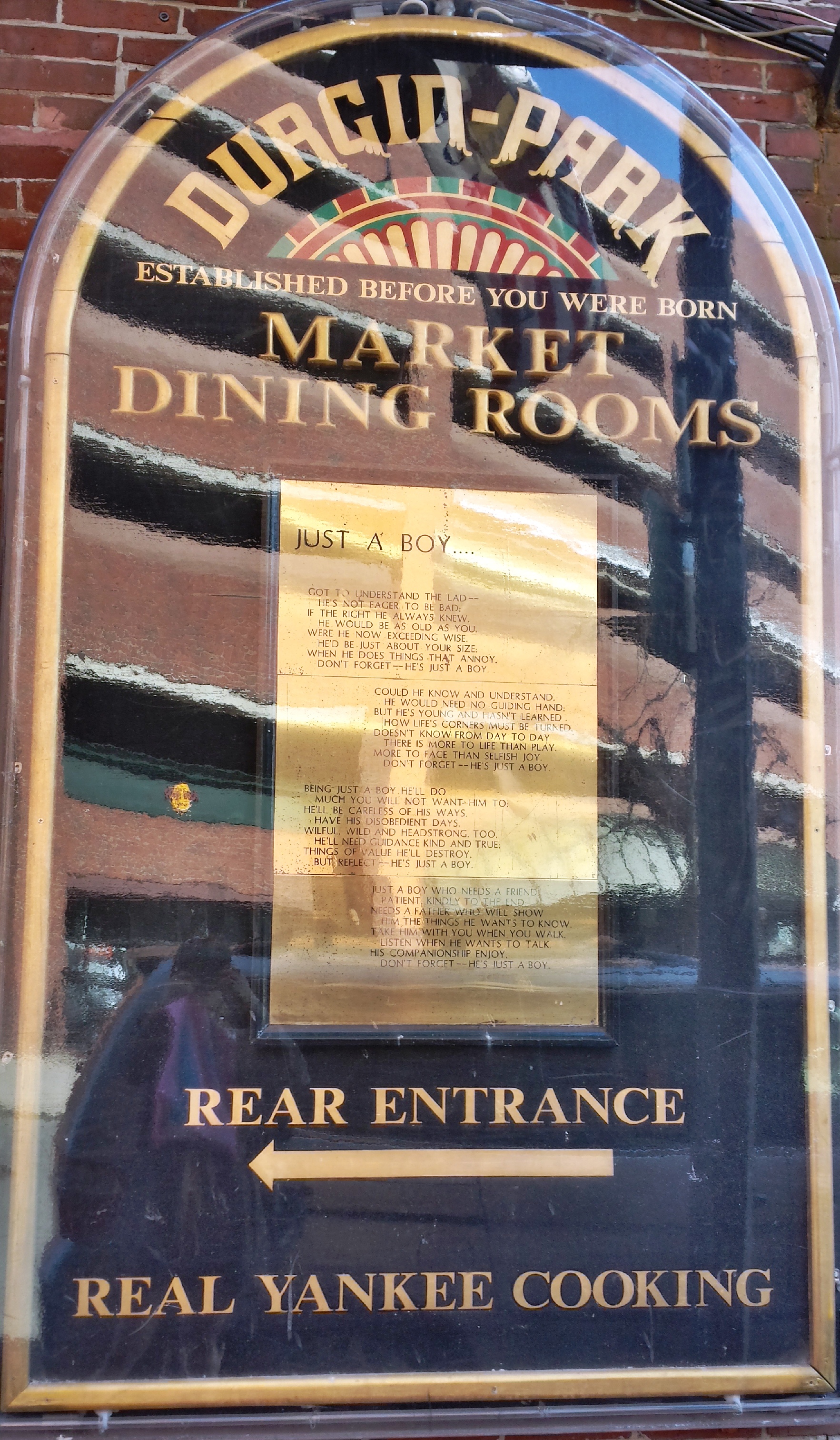

Figure 8: steel remnants of storage use Figure 9: landings and railingsUpon closer inspection, some of these remnant steel structures seemed to be connected in some way to the Durgin-Park restaurant--a centuries-old landmark established in 1827, just after the completion of the Quincy Market complex. The restaurant's billboard wears chipped and faded paint, but still stands stoutly on the roof of the North Market (Figure 10); it is the only rooftop advertisement between the three Marketplace buildings, which speaks to its recognized historical importance. In fact, just beside the restaurant's windows along the back wall is a plaque that boasts of its age with the slogan, "Established before you were born" (Figure 11). Other stores and buildings from before the 20th century also have some sort of marker or method of proudly indicating their age. Notably, Fanueil Hall, as a designated Boston landmark, contains a display tracking the changes that the building has undergone. These intentional allusions to Boston's early eras reveal the city's awareness about the site's historical importance; an awareness that, as Dolores Hayden notes in her book, The Power of Place, can become invaluable to the future development and cohesiveness of the urban community. "An evocative public program, using multiple sites in the urban landscape itself, can build upon place memory, in all of its complexity, to bring local history, buildings, and natural features to urban audiences with a new immediacy...working within an inclusive urban landscape history can connect diverse people, places, and communities, without losing a focus on the process of shaping the city. (228)"

Figure 10: the Durgin-Park Dining Rooms Figure 11: a point of pride.It vaguely occurred to me that I was being a bit of roadblock as I stood next to Faneuil Hall, camera raised, with people weaving and ducking around me. My attention and my lens, however, was trained on the buildings that towered over the Marketplace--much more modern buildings, obviously, whose great heights reflect the rapid advances in building technology during America's Industrial revolution (late 1800s/early 1900s); a marvelous Art Deco-style high-rise to the right of the South Market alludes to the geometric stylings of that particular art and architecture movement (Figure 12). The other surrounding structures, too, in both their relative heights and their architectural styles, created a scene of layers for anyone looking skyward alongside me.

Figure 12: an Art Deco high-rise sits haughtily above the Marketplace.I found myriad examples of this juxtaposition of the past and the present in the skyline in Blackstone Block as well, the most striking of which (in my humble opinion) was the view of distant high-rises looming behind the Union Oyster House's worn sign, captured in Figure 13.

Figure 13: a backdrop of modern office buildings accompanies the Union Oyster House's sign and one of Blackstone's old street lamps.Walking past Faneuil Hall and into the brick-paved walkway of South Market "Street" (which, along with its sister North Market St., used to be utilized as "actual" streets when horse-and-buggy was the main form of transport; with the advent of the streetcar, it was likely quickly determined that allowing cars and pedestrians in the same crowded area would be inadvisable, and the two streets were turned pedestrian-only), and lowering my sightline from the high-rises to the South Market building reveals its austere facade (Figure 14), characteristic of the time during which it was built. Similarly styled buildings, with unadorned, inset windows and red brick/grey stone, can be found in Blackstone Block--which was developed during the same era. Of course, not every part of the Market buildings is purely original. Often, however, any new additions allow the older parts to "peek through", as this water connection for the fire department on the other end of South Market does (Figure 15).

Figure 14: the seam. Figure 15: hose "sockets".The metal plate containing the "sockets" for the fire hoses are set into a small piece of what looks to be an earlier wooden facade; wood planks like these are found nowhere else on the building's exterior. Framing the planks, then, is the "new" stone used on the rest of the lengthwise facade.

A third example can be seen in Figure 16--a 1930 plaque for Faneuil Hall sits just above eye level, and just below modern security cameras that keep watch on the corner of the building. The two are from vastly different eras, but both are indications of the importance of the building that they are attached to. A fourth and final example is the lampposts that line the walkways between the Market buildings (Figure 17); the ostentatious, bubble-like lamps speak to the design aesthetics of the 1960s and 70s, which makes sense, given that they were more than likely put in place during the 1970s renovation.

Figure 16: signs of an important building. Figure 17: how very 70s.Lowering my camera lens all the way down to face the ground reveals the layers that can be found in the paving of the Marketplace's and Blackstone's streets and walkways. N. Market Street and S. Market Street, as mentioned previously, are paved with red brick; in many places along the two sister streets, patches of brick of different sizes meet at odd angles (Figure 18), likely due to asynchronous paving. Blackstone's streets are even more eclectic, with asphalt, brick, and four types of stonework coming to meet in the same square meter (Figure 19). Each material belongs to a different era, and they come together to create a quilt of the Block's history as one of the oldest areas of Boston proper.

Figure 18: breaks in the brick. Figure 19: street quilt.Indeed, Blackstone Block, with its street network designated and preserved as a city landmark (alongside Faneuil Hall and Quincy Market) is not only rich with traces and vestiges of early Boston--many trace are marked as such, explicitly or implicitly. As I made my way along the Block's interweaving streets, with alleyways branching off in every which direction, I found an example of explicit trace marking nailed into a brick wall along a small parking lot (Figure 20):

Figure 20: a little green plaque."Public Alley 102", declares the little green plaque, and underneath that reads "1670s". And in fact, Blackstone Block is easily recognizable in the 1676 map--the Block's overall shape and interior street structure hasn't changed much at all into present day--as it had already been well developed by the 1670s. The building composition, on the other hand (while many of the original buildings have been purposely preserved), has gone through several periods of change. In fact, this parking lot is one of the major structural changes (major, as it involved the complete demolition of a building and switching of land use) to Blackstone's complex web of buildings. The outline of the building that once resided on the lot's area is traced by a walkway that continues into a curved alleyway between two extant buildings (Figures 21 and 22).

Figure 21: the curved outline of a building that once stood, traced by a stone walkway. Figure 22: the parking lot.An example of an implicitly marked trace, then, is the term "ye olde" that the Union Oyster House's entrance sign boasts in script-like golden letters (Figure 23). The Old English spelling is used to evoke a sense of the Oyster House's age as one of the earliest establishments in the area alongside the Durgin-Park dining rooms, and on the back of the Oyster House building, a faded plaque with missing letters (Figure 24) adds to the authenticity.

Figure 23: "ye olde". Figure 24: missing letters.The sheer number of pictures that I took that are not included in this essay for the sake of length speaks to the nature of historically important areas like this site as eminently rich with highly visible traces, trends, and layers. While Anne Spirn notes that many cannot identify and acknowledge the significance behind these layers in the landscape--"Most people can no longer read the signs: whether they live in a floodplain, whether they are rebuilding an urban neighborhood or planting the seeds of its destruction...(11)", even the casual observer can find and delight at the "old style" architecture, restaurants, taverns, and shops that fill up the area, along with myriad other small signs that point to the site's past and its considerable age. Considering this, the future of the site is likely to continue in that nature--intentionally preserved and relatively stagnant physical form, but host to an array of shifting, modern, yet consistently commercial uses.

Works CitedHayden, Dolores. The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995.

Spirn, Anne. The Language of Landscape. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.