The West End Through Time

From Farmland to Subway Suburb

[Note: I have found it very helpful for my own analysis to assemble the maps involved in this project as a series of slides. By aligning the maps at the same scale and moving through them quickly, the patterns of development seemed more likely to stand out. If you would like to download a copy of these slides (8 total) to accompany the paper, click here.]

Introduction: An Early History

The West End’s early development was largely driven by its positioning on the original Boston landmass. About half of the West End’s area today was reclaimed from the Charles River during an incremental land filling process from the early 1800s through to 1950. This process and its consequences for the neighborhood are discussed in full detail in the previous assignment.

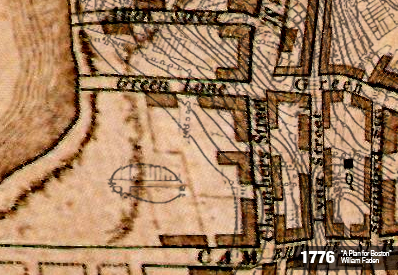

The earliest available plan with enough detail to focus in on the initial development of my specific site as a part of the West End’s growth is William Faden’s 1776 map of Boston. Shown in full in the last assignment, the following image is a close up of the approximate area of the site. In order to understand the role topography played in the sequence of development, I have overlaid the image with the contours contained in the Boston Housing Authority’s West End Project Report from 1953. With this overlay in place, it becomes clear that the majority of the built area occurs on the high ground. Herbert Gans describes the settlement of this time period in his book, The Urban Villagers, as a meeting ground between the “Back of the Hill,” where the servants to the aristocracy of Beacon Hill lived, and the lower-middle class families who had worked their way up from “the bottom of the slope,” meaning the dense, low-income waterfront areas. They used the flat, coastal areas for farmland through to the early 1800s (Gans, 5).

Many of the streets from 1776 were maintained through the majority of the site’s history. The two blocks furthest to the right in the image, bounded by Chambers, Staniford, Green, and Cambridge Streets, are the oldest residential blocks on the site. They form a typical row house style block with a narrow block width, defined by the dimensions of two sets of row houses plus a buffer of recreational space between. While the site shows development spreading along the major street fronts, the rest of the area is mostly devoted to farmland. The only nonresidential structure appears to be the Old West Church, demarcated by a black square, and built as a wood frame building in 1737.

By 1814, the West End’s development in relation to Beacon Hill becomes physically embodied with the transfer of the Beacon Hill street grid to extend across Cambridge Street, shown above. This creates a logic for the residential development of the West End’s farmland. Streets are often named in pairs with their Beacon Hill counterpart, such as North and South Russell Street. Despite a strong North-South street grid, the East-West streets do not have a readily apparent organization, resulting in a few awkward block formations. In select cases, the affluence of Beacon Hill made the jump across Cambridge Street in the form of specific buildings, like the Harrison Gray Otis House in 1795 and an elaborate renovation the Old West Church in stone in 1806 (both shown on the map outlined in red). Both buildings were sited on the highest point of the landscape, which traditionally symbolizes affluence (Refer back to the 1777 map for the contour lines).

The remaining farmland, closest to the River and likely marsh-like in quality, was built up to become docks. Thriving copperworks and shipyards were already in place along the wharfs on the West End’s northern shoreline, but as of 1814 the only structures on the docks within the site are used for a market.

A second major waterfront development, the West Boston Bridge, was completed in 1792, just barely visible on the far left side of the 1814 map above. The wooden bridge connected the foot of Cambridge Street directly to Main Street in Cambridge, and Harvard owned a large share in its construction, operation, and toll collection. It took the place of a ferry service that operated along the same route (Record of Streets, Boston Street Laying-Out Department, 1910).

1867: An Industrial Neighborhood

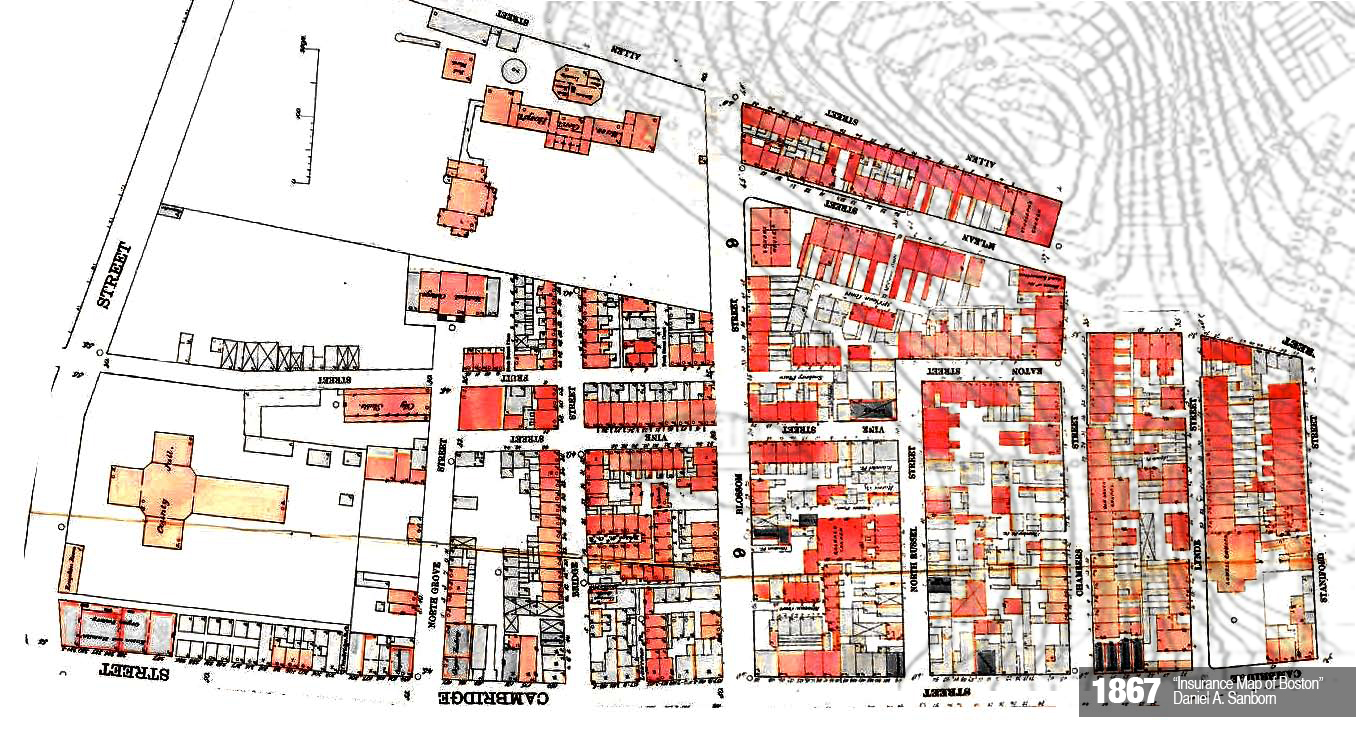

By 1867, the wharfs along the Charles River are full of activity on the site, and continued land filling has made even more space available for growth. The primary use of the largest wharf on the site is as a lumberyard. Its presence likely influences the nature of other kinds of developing trades, since the other examples of industry on the site are two organ factories near the wharf. In addition, the site’s commercial activity includes six carpenters, four furniture stores, two painters, and one carriage smith. The only non-lumber commercial activity appears to be Danielson’s Carriage Facility, a collection of about a dozen stables just north of the jail (shown as the largest aggregation of red on the map above). Clearly, the presence of the lumber docks has driven the character of the site’s economy.

The infrastructure of the West End at this time gave the industry key transportation access, including the steam railroad hub further north of the site, which would eventually become North Station, and the Boston’s first streetcar line along Cambridge Street running from Harvard to Bowdoin Squares across the West Boston Bridge. The railroad allowed for goods and raw materials to be shipped all over New England, and the streetcar brought in customers from wealthier areas of Boston for the finished wood products. Mixed-use, ground floor retail establishments dominate the Cambridge Street streetfront.

From 1820 to 1850, the first wave of immigration hits Boston, mostly from Ireland. The West End’s “distinctive function” during this time was “an overspill area” for the newly immigrated work force that could not find room to live in the nearby North End (Gans, 6). In the 53 years between the previous two maps, the area has become far denser to respond to the need for working-class housing. While the Sanborn maps of this period to not record the type of dwelling constructed, the newer blocks are built with a higher proportion of wood when compared to the two original blocks dating back to 1776. This suggests that the new residences were built cheaply and quickly to accommodate the new immigrants. Balloon-frame construction had reached the east coast from Chicago by this time, which dramatically changed the construction process’s efficiency (Jackson, 126). See the materials map below, with brick construction in red, wood construction in gray, and ghosted contour lines to help show the relative age of each blocks’ structures.

Block patterns at this point also become a lot more disjointed, which is likely an effect of the speed with which structures were built. Instead of each block containing two rows of housing and back lots, the streets carried over from Beacon Hill, created blocks that were just too wide to ignore the potential for inner-block development. While Beacon Hill residents may have had the luxury of spacious back lots, the quickly multiplying population of the West End required more efficient use of space. Freestanding houses began appearing within the perimeter of the wider blocks, particularly those along Cambridge Street, and narrow alleyways penetrating into the block were their only means of access. Because the lower-income residents of these structures had no need to park a carriage, the alleyways only had to be wide enough for pedestrian use and adequate ventilation. This resulted in a messy, ad-hoc, tertiary road system with cul-de-sacs often named as extensions of the main access way, such as Fruit Street Place and Fruit Street Court.

The blocks on the newest land along the river, however, remain sparsely developed because two large institutions, Mass General Hospital and the Charles Street Jail, buy large plots of land to begin their campuses. The jail is opened in 1851 to replace an older jail further north in the West End. Other municipal buildings surround it to act as a buffer between the jail and the residential area, such as the city stables and morgue. Mass General Hospital (always shown on the map in a darker institutional blue) opened as a teaching hospital in 1818, and Harvard Medical School moved out of Cambridge to become part of this new campus. It was intended as a hospital for the poor, since wealthier patients who could afford a doctor were cared for in their homes. The jail and the hospital, combined with the other institutions present in the West End at this time including St. Joseph’s and Old West Church, an unnamed colored church, and a Good Samaritan clinic, paint a picture of a working-class neighborhood already in need of a few charitable services in order to meet its basic day-to-day needs.

1900: The Neighborhood Diversifies

At the turn of the century, the West End once again became home to the newest waves of immigrants, particularly Russian Jews and Italians (Gans, 7). To accommodate for this population flux, the major new building type changes from three-story, single-family houses to three to five-story apartments. For the first time, tenements are labeled on the Sanborn maps, noted above in brown. About one-fifth of the housing becomes multi-family, which in many cases is concentrated on the inner-block alleyways. The colored church converts to the area’s first synagogue, and a much larger school is built in addition to the new housing.

The lumberyard relocates inland from the wharf after the Charles River Embankment is constructed along its old site on the river. The local economy of the West End has attracted other trades in addition to the wood industry, such as a blacksmith and a tin shop. New forms of service-based retail open, including three laundries, a hotel, and a drug store. The strong retail base along Cambridge Street begins to trickle down the blocks to form some secondary commercial areas along Green Street and Fruit Street. This is likely the result of the construction of the Longfellow Bridge from 1899 to 1906. The increased traffic along Cambridge Street spurred a parallel strip of retail development. The new volume of traffic was also likely to be a factor in the carriage company’s expansion, as it has doubled in size.

Also, note that Mass General has added several new buildings to its campus and has begun buying up local residences beyond its allotted area. They are used as temporary dormitories for students attending Harvard Medical School. The Boston Lying-In Hospital for Women, one of America’s first maternity hospitals, opens nearby in 1832. It’s also one of the first of many pioneering medical facilities that Mass General attracts to the area, and the Lying-In Hospital eventually becomes incorporated as part of Brigham and Women’s.

1937: Blight Sets In

Consistent with the national trend of industry’s flight from the inner city, the 1938 Sanborn map shows that both the lumberyard and large organ factory have moved off the site. Kenneth Jackson attributes this to the proliferation of the truck in 1910 for industrial shipping (Jackson, 183). The second organ factory has also left the West End, but it is replaced by a small bottling facility, which remains the only industrial presence on the site. The carriage facility, also outdated by the advancement of automobiles, has gone out of business. Mass General absorbs the land left by the carriage company and the lumberyard.

There are even fewer single-family residences as of 1938, and just over half of the neighborhood is listed as apartments. Some structures are even noted as “vacant and out of repair” on the map, which is unprecedented in the history of the neighborhood thus far. Combined with two new settlement houses and a Salvation Army outpost, it appears as if the West End demographic trend is reaching lower and lower income levels. Some of this can certainly be contributed the Great Depression, but local changes could be to blame as well, especially if many West Enders worked at the lumberyard or organ factories and are now out of a job.

Most of the tenements from 1900 have been razed and constructed as new apartments, but several new ones have appeared. Gans stresses that the while the vast majority of apartments in the West End were low-rent yet perfectly adequate units, the tenements were often left vacant because of the poor living conditions they offered. Landlords were desperate to fill these vacancies, which often led to even poorer residents moving in with lower standards for quality of life. This only exacerbated the West End’s image as a blighted neighborhood (Gans, 389). I have compiled the tenements and abandoned buildings shown on the previous maps on the image below, which shows that they are largely concentrated along the inner-block alleyways that offer poor access, light, and ventilation and thus very undesirable places to live.

Even the Otis House, once an elaborately designed, wealthy residence has been converted into a boarding house with a ground floor laundry. When Cambridge Street is widened in the 1920s, it is seen not only as an opportunity to decongest the city as it become more dependent on cars, but also as a social barrier. It helped to disassociate the increasingly low-income oriented West End from the upper-middle class neighborhood that developed on the gentrified “Back of the Hill,” despite the fact that their early demographics were essentially identical as discussed earlier in this paper (Gans, 6).

1951: The Beginning of the End

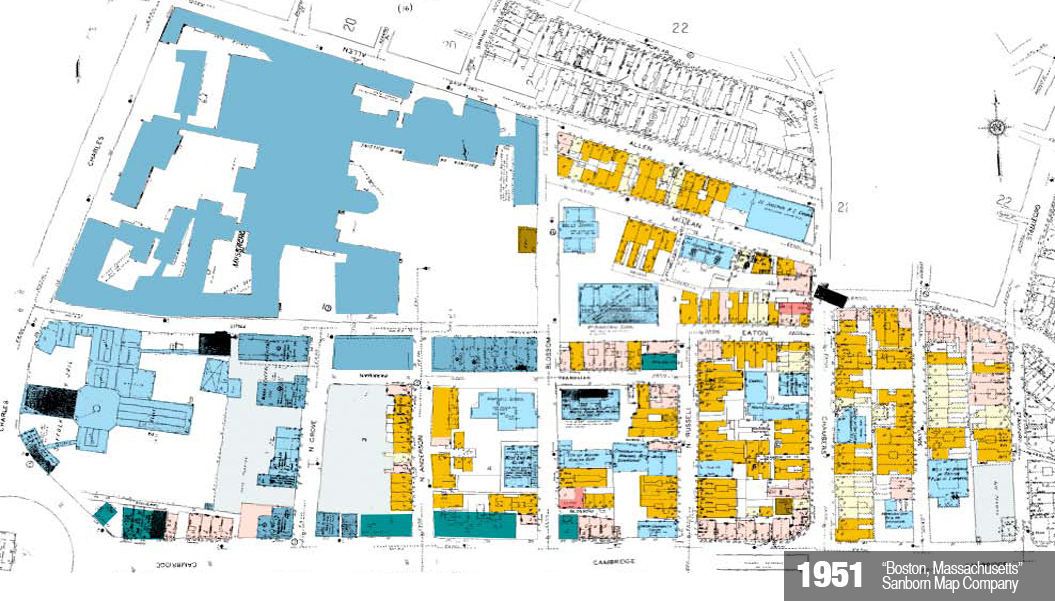

A sign of things to come, some demolition work occurs in the West End between 1938 and 1951 to make room for the huge influx of cars in the city, coinciding with the construction of the Central Artery. Large portions of West End blocks, many of which included tenements, are flattened and paved for parking lots. Two of the three are designated for Mass General parking. In addition, about half of the retail establishments along Cambridge Street are torn down and replaced by four gas stations. These gas stations are the only independent structures for commercial activity on the site with the exception of the tin shop dating back to 1900 and a storage facility. No parking is added for residential use, since most West Enders are not at an income level where they can afford a car. However, a new public transit option becomes available to residents in the form of a new MBTA stop on the site of the former organ factory (All transportation related buildings are marked on the above map in turquoise).

At this point, virtually all residences are multi-family apartments of first and second-generation Italian, Jewish, and Polish households (Gans, 9). There are only 27 single-family units still in existence, all of which are clustered near those same original 1776 blocks between Chambers and Staniford Street. Once associated with the prestige of the Otis House and the Old West Church, the families living on these two blocks likely remained slightly more affluent than the average residents and most resistant to the multi-family reuse of buildings sweeping through the rest of the West End.

A third settlement house opens, demonstrating that the economics of the neighborhood has not improved since the original two settlement houses opened around the Great Depression. Mass General Hospital expands into the residential buildings left vacant as well as many of the old city properties by the Jail, and its growth finally extends all the way to front Cambridge Street. Overall, the site has homogenized into either institutional use of some sort or multi-family housing. The vibrant streetscape of stores and hotels in the early half of the century has mostly died off, besides a few mixed-use clusters.

It is right around this time period that the West End is first slated for urban renewal. Given the trends observed on the site since 1867, it is understandable why the West End was viewed as a slum in need of drastic urban renewal. A hugely successful institution, constantly growing, dominates the site. Mass General has solidified is position as an asset not only as a resource for the public health, but also as an economic driver for the city. It’s in the city’s best interest to encourage its progress. Conversely, a lower-middle class, single-family farmland has dissolved into a tenement neighborhood of some of Boston’s poorest residents who are heavily reliant on public services. The flight of industry to the suburbs disrupted the local economy, creating fewer jobs for skilled laborers and an overall decrease in income levels. The cheap rents available only attract even poorer residents to the area. While many scandals erupted out of the interests at stake in the West End’s redevelopment, including vast exaggerations of the poor living conditions there and the extent of the neighborhood’s blight, the Sanborn maps provide an impartial source of data to accurately view the area’s development patterns.

Present Day: The renewal of a Subway Suburb

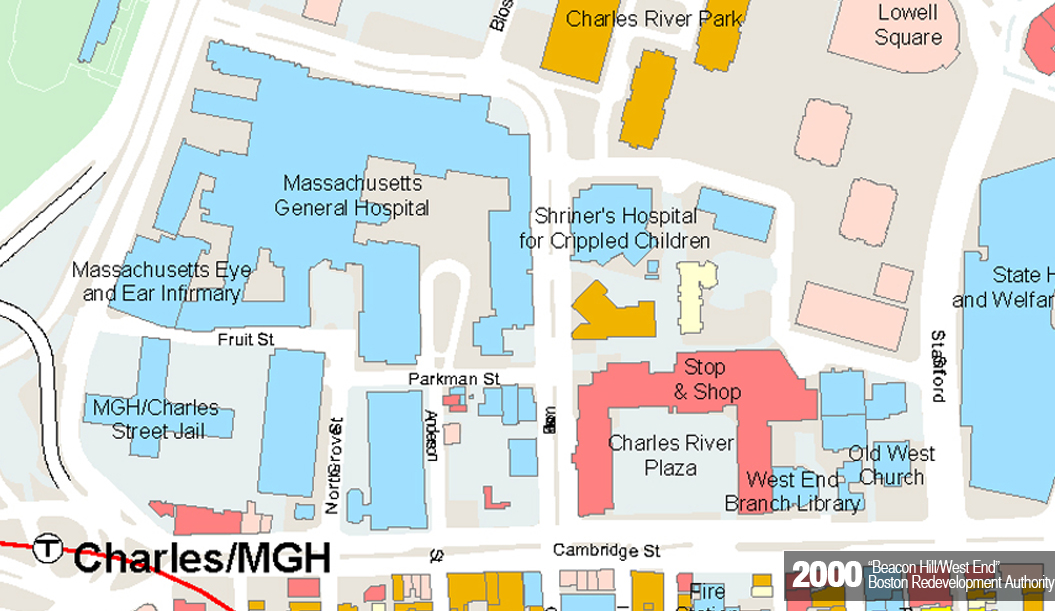

Within four years, almost the entirety of the West End was demolished and reconstructed by the Boston Redevelopment Authority under the Federal Housing Act of 1949. In order to attract the upper-middle class back to the inner city business districts from their suburban homes, the BRA resolved to develop the area as a subway suburb called Charles River Park, with all the convenience of urban life within a typical of a suburban environment. Tall residential towers took the place of apartment rows, underground parking became available for every resident, and generous amounts of outdoor recreation space served as communal front lawns. The entire development was very consistent with the most fashionable trends in urban design, and it embodied many of the principles popularized by Corbusier, particularly the residential towers and ratio of built area to open space. Because this development was all constructed around the same time, the area has been relatively unchanged since its implementation in 1962.

The Old West Church, the Otis House, the Charles Street Jail and St. Joseph’s Church were the only buildings that survived the redevelopment, except of course the Mass General campus and the few buildings it incorporated before the demolition, such as its repurposed use of the adjacent Winchell School. These saved buildings, which once stood out on the site plan as the largest structures in the neighborhood, now stand out as some of the smallest. The entire scale of the site changed dramatically from small clusters of buildings and nodes of common use to monumental, single structures that segregate uses such as the Charles River Plaza, which acts as a central location for almost all of the commercial activity on the site. The street grid remains relatively maintained for its value as infrastructure, with many of the secondary and all of the tertiary streets removed to simplify circulation. The plan also accommodates for satellite hospitals to move into the area, attracted to the prestige of Mass General, setting up the city of Boston economically as the health care mecca that it is today.

Conclusion

The redevelopment of the West End is generally viewed as one of the worst mistakes in the history of urban renewal, and many people began to criticize the project within a few years of its completion in 1962. While the decision to revitalize the area is consistent with the patterns presented in its development since the turn of the century, the final result does not justify the displacement of 7,000 of its original residents.

In my experience, I have found that most of its residents aren’t visible on the site, and they circulate mostly through the underground parking to their units instead of taking advantage of the large amounts of recreation space between towers. In an effort to foster more of a community, the new residents are beginning to embrace the image of the old West End as a legacy that brings them together. Instead of referring to the area as Charles River Park, many signs around the area refer to residents as West Enders. In addition, there has been a movement to rename the green line MBTA stop “Science Park/West End” to revive interest in the neighborhood’s history. A vibrant, if low-income, community is a trademark of the old West End. Although it no longer exists in physical urban form, the West End’s culture and legacy are beginning to take root on the site once again.