Rat Behavior in Response to Reward

Changes:

A Matching-Maximizing Model

Mathew Tantama, Margaret Blayney, Dezhe Jin

9.290 Spring 2004 Midterm Project

![]()

Results:

By approximating the ratís behavior both as a constant switching frequency signal and as a Poisson process, we found the same relationship between the observed stay time on the rich lever (TA) and the lean side reward rate (lA/Q).

![]()

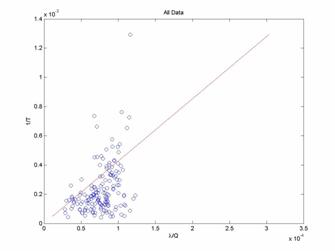

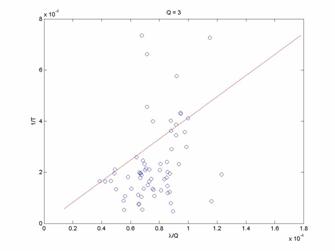

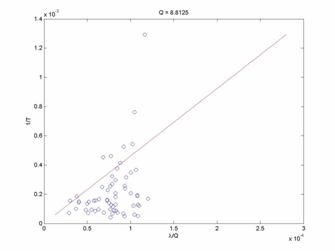

We see from Figure 1 that the theoretical fit to the experimental data is not good.† It appears that there is a large bias for the observed leaving rates to be smaller than predicted.† In fact, it may be that there is actually an exponential relationship, but this is purely a mathematical observation of which it is not clear what physical meaning and exponential relationship would represent.

The poor fit of the theoretical model to the experimental data may in fact be an artifact of combining all data into one visualization.† It may be that the model works well for some reward ratios but not for others.† In order to investigate this possibility, we can group and plot experimental data of the same reward ratios.

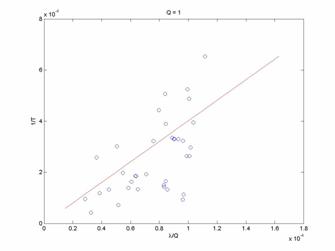

In Figure 2, it is apparent that the theoretical model does indeed fit the experimental data to a greater extent. †The fit still contains large residuals, but qualitatively the better fit may indicate that this approach to model building may be valid and useful. †Now, considering other reward ratio data groups shown in Figures 3 and 4 for Q=3 and Q=8.8125, we see progressively worse agreement between the theoretical model and the experimental data. †There is an increasing bias for the leaving rate (1/T) to be less than the predicted values as Q increases. †This may be a severe shortcoming of the model.

†

†

Discussion:

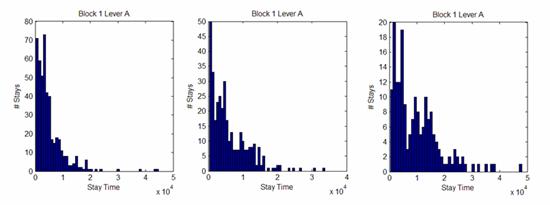

Surprisingly, treatments of both approximations Ė constant frequency or Poisson process - of rat behavior using this matching-maximizing approach resulted in the same theoretical model which fit poorly to the experimental data. †This indicates a failure or failures in the chosen approach and algorithm. †The first and most obvious failure may be that the rat does not use a matching plus reward maximization strategy. †This is a strong possibility, but it is also useful to consider other possible failures before discounting this approach. †Model building such as this is strongly dependent on the assumptions and approximations made in the initial stages, and as such failures in these steps may cause large propagations of error leading to poor agreement as observed in our case. †The sever approximation made in the constant frequency case is an obvious one. †Examining histograms of our stay times, obviously there is not only one occupied bin as would be the case were the rat in fact to have behaved with a constant frequency of switching. †Instead, as seen in Figure 5 there is a decaying distribution of stay times.† As such, it was expected that this simple case would contain large error. †It was, however, a surprise that using a more complex approximation of the ratís behavior as a Poisson process resulted in the same theoretical model. †This result was immediately a strong indication of a failure in the approach. †One would expect that improving assumptions and decreasing error in the approximations made to build the model should result in a better fit. †In this case, both resulted in the same poor fit.† One explanation for the failure of the approach upon moving to a more complex behavioral approximation may be that the behavioral approximation itself was still extremely flawed.

As seen in the center and left histograms of Figure 5, the distributions of stay times on a given lever are often poorly described by an exponential decay. †As such, it may be that even using a Poisson distribution to approximate the ratís stay behavior is an extremely poor approximation. The resulting large errors cause this supposedly more rigorous case to in actuality contain comparable large errors as the simple constant frequency calse. †This may be the reason the theoretical models approximate to the same function with no improvement from using the Poisson process approximation over the constant frequency approximation.

Conclusion:

We examined the validity of using a matching-maximizing approach to modeling rat behavior in response to changes in reward ratio given concurrent variable reward interval schedules.† Initial analysis using a simple approximation of the ratís behavior as a constant frequency signal showed some promise in modeling cases of equal reward rates.† The simple model did not perform well for increasing reward ratios away from unity, and did not perform well overall. †The interesting features of the initial analysis did merit examination of a more physically reasonable case in which the ratís behavior was approximated by a Poisson distribution of stay times on the rich side lever. †Surprisingly, this more rigorous approximation led to the same model indicating a failure in the matching-maximizing approach. †It is proposed that the two main reasonable hypotheses for this model failure are: (1) The rat does not use a matching-maximizing strategy to adapt to reward ratio changes. (2) The mathematical approximations made to describe the rat behavior were too crude to reasonably describe the actual physical process. †Regardless of the failures of this model, it may be interesting to further investigate its utility using more rigorous and physically relevant approximations.

References:

1. Gallistel, C.R., Mark, T.A., King, A., Latham, P.E. J. Exp. Psych. Anim. Behav. Proc. 2001, 27, 354-372.

Acknowledgements:

We wish to thank Gallistel and co-workers for providing data sets. †We wish to thank Dr. Dezhe Jin for directing this project.