Thursday, Nov. 15, 2007

5 - 7 p.m.

Bartos Theater

Abstract

The fragmenting audiences and proliferating channels of contemporary television are changing how programs are made and how they appeal to viewers and advertisers. Some media and advertising spokesmen are arguing that smaller, more engaged audiences are more valuable than the passive viewers of the Broadcast Era. They focus on the number of viewers who engage with the program and its extensions -- web sites, podcasts, digital comics, games, and so forth. What steps are networks taking to prolong and enlarge the viewer's experience of a weekly series? How are networks and production companies adapting to and deploying digital technologies and the Internet? And what challenges are involved in creating a series in which individual episodes are only part of an imagined world that can be accessed on a range of devices and that appeals to gamers, fans of comics, lovers of message boards or threaded discussions, digital surfers of all sorts? In this forum, producers from the NBC series Heroes will discuss their hit show as well as the nature of network programming, the ways in which audiences are measured, the extension of television content across multiple media channels, and the value that producers place on the most active segments of their audiences.

Speakers

Jesse Alexander is a co-executive producer and writer on Heroes and an executive producer on the Heroes spinoff Origins. Previously, Alexander was an executive producer on ABC’s Alias, and a co-executive producer on ABC’s Lost.

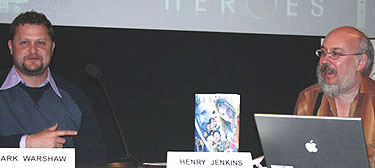

Mark Warshaw is a writer/ producer/ director who joined the Heroes team in 2006 to help launch their transmedia department. Prior to joining Heroes, Warshaw spent six years on the TV show Smallville, overseeing all of their digital, DVD and integrated advertiser marketing initiatives.

Moderator: Henry Jenkins is co-director of Comparative Media Studies and the Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities at MIT. He is the author of several books on various aspects of media and popular culture including Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide.

Podcast

A podcast of NBC's Heroes: Appointment TV to Engagement TVis now available.

Webcast

A webcast of NBC's Heroes: From Appointment TV to Engagement TV is now available.

Summary

[this is an edited summary, not a verbatim transcript]

This forum opened the Futures of Entertainment 2 conference at MIT.

Moderator Henry Jenkins asked the speakers to begin by describing their roles in the production of the NBC series Heroes.

|

Jesse Alexander said his job as co-executive producer involves supervision of the writing team and oversight of the story’s continuity. He also manages the Heroes brand as it moves into other media platforms. He doesn't control money, he said, but because of his seniority he has to think fiscally.

Mark Warshaw, a producer, joined Heroes last season to help launch its transmedia department, which is charged with extending the series beyond the television screen. He said he has always worked on the digital-extension side of television and now oversees the program’s website, Heroes 360, as well as the production of DVDs and other new media.

Jenkins explained that the subtitle of this forum identifies a major change in the nature of TV viewing. “Appointment TV” refers to the experience of viewers in the era before cable and such devices as digital video recorders who tune in to programs broadcast at scheduled times. “Engagement TV” is a label for the behavior of many of today’s viewers who choose from a much wider range of content and watch TV whenever they wish to. He asked whether these and related changes have altered the way producers think about television in the 21st century.

Alexander, who was a producer on the show Lost, believes that program established the idea of engagement television. The show’s producers consciously exploited a range of media beyond TV to sustain interest in the show. Finding ways to generate revenue especially when producing an expensive series like Lost or Heroes is important and a transmedia approach – using content on multiple, often overlapping media platforms – is a good way to do this, he said.

The discussion shifted to the challenges of producing serialized television in which storylines continue over multiple episodes. While both Alexander and Warshaw described this a new phenomenon, some audience members pointed out during the discussion segment that serial television has been around for a long time, most notably in soap opera.

Recently, the writers said, networks have tended to prefer episodic content in which plots are resolved in a single episode. At the same time, Warshaw pointed out that it's easier to tell serialized stories today because viewers with access to a full season of DVDs can refer back to previous episodes.

Alexander said the producers of Lost had not anticipated that more than twenty percent of the audience would watch the program using digital video recorders and that tens of millions would watch online. Even though these viewers weren't watching in the traditional way, they were still participating in the community and fan culture centered on the show. One lesson here, Alexander said, was that TV series might need to adapt to a world in which man viewers watched programs in disjointed, non-sequential order.

Jenkins asked the speakers to discuss the television writers’ strike, which has just begun at the time of the forum.

|

Warshaw pointed out that DVD of the first season of Heroes sold more copies than any DVD in the history of television in part because it was released globally. For each $50 boxed DVD sold, the writers collectively receive four cents, he said, while the company that manufactures the boxes receive 50 cents per set. This seems unfair, Warshaw said. Writers have a right to be paid fairly when their content is distributed, whether it is presented on television or on other media platforms.

Alexander explained that the Writer's Guild had agreed at one time to give the studios a financial break to help launch what was then the new DVD format. This agreement was made on the understanding that an equitable payment scheme would be renegotiated in the future. In retrospect, he said, this was naive.

Warshaw said that most writers depend on residuals – payments to creators, writers and performers for sales or screenings that occur after the initial broadcast. Because of changes in the way people view TV shows and because of the proliferation of platforms or sources for content related to TV shows, the definition of residuals must be enlarged to include such new platforms as DVDs, the Internet and other media. Today transmedia content is classified as promotional, and its creators aren’t paid in the same way as they are for televised content. For example, the creator of a webisode, an mini-episode of a show presented online only, is paid only once regardless of how many times it airs.

As Lost was evolving into a transmedia vehicle, Alexander said, he was more than willing to do additional work to develop ancillary content for the series. In this early phase, such material was used to connect fans with the program and was not a source of advertising.

Jenkins returned to the topic of serialization and asked how the networks viewed this approach to programming.

According to Alexander, the networks are uncomfortable with stories that extend over weeks and months. They prefer episodic content that allows people to drop in and out of a series. This, they believe, will allow as many people as possible to watch on a regular basis. Serialization, on the other hand, creates a more engaged fan base. The result is a tricky situation for the networks and the writers. Everyone wants to make sure enough people watch every week, so the producers are constantly experimenting with form and content. This was one reason for the numerous flashbacks in Lost. This strategy allowed for episodic content within each episode, but also permitted the larger story to extend across many weeks. Serial narrative, Alexander said, works well when people can control the pace at which they view the story, as they do in a transmedia world.

Creating a story that engages people across a season or several seasons is the great challenge for writers of serial content. Alexander acknowledged that he and his writing team made a mistake in the current season of Heroes by not establishing a clear narrative thread for the primary characters. In the first season, there was such clarity, a kind of destination for the story. He hopes this weakness will be corrected in the third season.

|

Jenkins asked about the importance of the backstory in a series like Heroes and how the creators decide when and how to break out of the narrative timeline.

Alexander said that they don't always know the backstory and that it's a challenge to decide when to insert a flashback. People must care about the characters for the backstory or flashbacks to matter. Timing the flashbacks was something he thinks they did very well in the first season. This year he thinks they waited too long into the season and the technique didn't work as well.

According to Warshaw, transmedia content—that is, content located in webisodes or other platforms separate from the broadcast material -- is especially useful for telling backstories or expanding on them. If an important backstory is planned for the TV show, he and his team can begin setting the stage for this through other channels.

Jenkins asked the speakers to explore the role of transmedia content in more detail. He asked about the role of comic books in the development of characters and how central to the televised story transmedia content needed to be.

Alexander said that a show’s content must first serve the broadcast audience; transmedia material is used to appeal to the most engaged fans. Several characters who played minor roles in the televised version of the show became much more central characters online. The character Risk, for example, is used online to plant the seeds for future developments in the TV program. In this case, the character was created on the TV show, was moved into other media and then back onto the TV program.

Warshaw stressed the importance of maintaining consistency between television and transmedia content. His transmedia team reviews the scripts and works closely with the writers to create content channels for every type of Heroes fan. These may include different characters, different content and different forms, but all must be consistent with one another. He reiterated the point that transmedia content, once viewed relevant only for promotion, is now taken more seriously; the same production standards are expected for transmedia formats as for television. Everyone, according to Warshaw, is demanding new types of content to serve different purposes. Because fans want rich content, the advertisers do as well and they are beginning to pay for cross-media advertising. Many advertisers now want their messages to be extended through a fan experience that lasts beyond the 60 minutes of the TV show.

|

Warshaw told a story to illustrate the global response to Heroes. The producers and cast visited France before the program premiered in that country and arranged a pre-broadcast event. To their surprise, the event drew an audience that completely filled what he said was the largest theater in Europe. How had so many people heard about Heroes? They had been downloading episodes online. The program has fans like this around the world, he said.

Discussion

QUESTION: Does transmedia storytelling work from an economic perspective?

ALEXANDER: Absolutely. It's becoming incredibly successful and very lucrative.

WARSHAW: Advertisers keep coming back to the table and want access to multiple properties and channels.

ALEXANDER: We're now seeing Webisode sponsorships.

WARSHAW: These are paid for by advertisers, so there is no cost to the studios to create the content.

QUESTION: Can you talk about the separate story lines. Are you tempted to use a different writer for each character’s story?

ALEXANDER: We work in teams and plan for a few episodes at a time. Teams of writers take on characters and their stories, and this allows for continuity.

QUESTION: Online, your Web site allows fans to create their own heroes. How will user-generated content affect character creation and introduction?

ALEXANDER: We might use fans’ characters, but the fans won't be compensated. We're not even compensated for transmedia content at this point. We could recognize them in other ways, though.

QUESTION: How do you deal with fan content that seems to break the Heroes brand?

|

ALEXANDER: We love it, we couldn't be more excited than when fans are committed enough to create content.

QUESTION: Is there fear from the networks about this?

ALEXANDER: The networks are learning they don't want to crack down on the fans.

QUESTION: This discussion has been very positive about transmedia material. But perhaps some skepticism is needed. What are your reservations about this whole process, about the scale or speed of your success? You are acting as if it’s a simple matter to jump between media forms, that what works on the TV screen will also work in a comic book format or in streaming video. That seems troubling from an artistic perspective. For example, it took television ten or fifteen years to figure out that the reduced visual scale of the TV screen differentiated it in essential respects from the movie screen.

ALEXANDER: My creative thinking is influenced by gaming where the story can be layered on top of the medium. We are approaching the story very differently for each channel, though.

WARSHAW: We try to take advantage of the medium we are working in; but regardless of the media, we are still telling the Heroes story.