| interactive television | |||

|

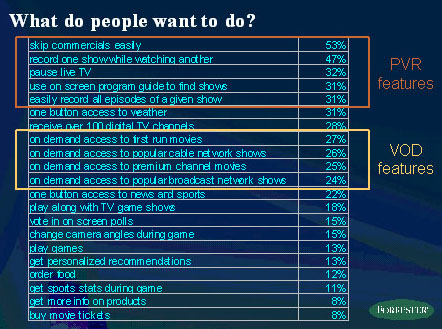

The introduction of the digital video recorder (DVR) has significantly altered the ways many consumers relate to television content — offering a simple way to access what they want to watch when they want to watch it. How has this new interface altered consumer behavior and their perceptions of the medium? What new models for interactive television are starting to emerge in research labs and think tanks around the country? Josh Bernoff is a principal analyst for Forrester Research who has done extensive analysis of the ways that TiVo and other digital recorders are impacting American media consumption. Dale Herigstad of Schematic TV is a leading figure in the American Film Institute’s workshop on interactive television design. Summary Bernoff showed an example of what he believes is poor design: the interface of TV Guide Interactive, a program guide for digital cable. The main menu contains a clutter of buttons that are not necessarily organized by what functions are used most often. The programming grid shows too few listings at a time, and requires the user to scroll frequently. On all pages, one-third of the screen is used for advertising programs and channels. The interface is not optimized for the benefit of the user, and therefore fails. Bernoff says interface designers should ask three basic questions: Who are the users? What are their goals? And how can they achieve these goals? One way of understanding users is by constructing models of different types of viewers. These "personas" are based on user goals, attitudes, and behaviors distilled from observation or interviews. Personas are presented in vivid narrative descriptions. For example, one might be a middle-aged woman who recently purchased digital cable and watches mainly primetime programs; another persona could be a college student who watches late at night. Since there are many personas, it is useful to study those that represent a large percent of viewers. Designers need to think about how each persona might use their interface. TV viewing is an impoverished interaction, involving only a remote control and a screen. There is a limited set of tasks to accomplish. When thinking about users' goals, designers should avoid the "second system syndrome" and not add so many functions. When things require too much effort, users give up easily. Bernoff identified some basic TV interface design principles. The first and most important principle is designing for features that people actually want. For example, WebTV had a great interface design, but it made no difference because nobody wanted to use the Internet on his or her television. A survey that polled 6,000 U.S. consumers showed the television enhancements in which people were most interested.

The top five responses were the features of a Personal Video Recorder, or PVR like TiVo: 53% said they wanted to skip commercials easily, while 47% wanted to be able to watch one show while recording another. About one-third of the sample wanted to pause live TV; use an on-screen program guide to find shows; and easily record all the episodes of a given show. Slightly further down the list of desirable features were those of video-on-demand. Over a quarter of the sample desired on-demand access to first-run movies, premium channel movies, and both cable and broadcast network shows. The sixth most popular request was for one-button access to weather, which was the only non-programming related task. The survey clearly showed what people did not care to do on television, such as get sports statistics during a game, or buy movie tickets. Another important principle is to have a consistent, asymmetric design for both the screen and remote interfaces. Common tasks should be easy to do. For example, given the enormous demand for access to weather, it could have its own button on the remote. Not all viewer actions are equally frequent or important, and the interface should reflect that. Finally, details matter because they can be the difference between a merely usable interface and a lovable one. To conclude, Bernoff gave a demonstration with his own TiVo, which he considers a lovable device. TiVo's only weakness is a challenging set-up, but afterwards it is easy to use and meets all the important design principles. The homepage, "TiVo Central" is not visually complex or crowded by unnecessary icons. The viewer can navigate through the menu options using the same few actions. The programming grid is larger, and recording programs is an easy task. Finally, an example of how details can add value to a system is TiVo's time bar, which helps viewers skip through programming. TiVo's attempt to incorporate non-TV related features has been successful because of consistency in design. Some devices have WiFi (wireless fidelity) access, allowing the user to program TiVo from a computer elsewhere. Meanwhile, through TiVo the user can access digital pictures or music stored on the computer. Overall, TiVo is a great example of obeying interface design principles. DALE HERIGSTAD believes that television is essentially a collection of rich media screens controlled by the viewer. When viewers are faced with up to 500 channels, better navigational tools are needed for people to get what they want. Herigstad is interested in exploring other possible control models in such a rich media environment. He has worked on several experiments and applications with enhanced television, integrating content with the interface. The underlying design philosophy in all projects has been to create a simple but powerful interface. Herigstad discussed several examples of creative interface design. An early system was Time Warner's video-on-demand trial in 1990, which experimented with navigation in 3-dimensional space. Menu items were arranged in a carousel format, which the user rotated with the remote control. Sony Surfspace was another electronic program guide with 3-D navigation. Instead of scrolling through a text grid for programming, the Surfspace user browsed through several layered "subspaces" of content. Each subspace was branded by different networks or themes, and played streaming video previews of shows. Several shows could be sampled at a time. Users could also customize the interface, making their own subspace for favorite programming. There are also possibilities for interacting with TV programming itself. For example, Herigstad and others worked with CBS to create CSI Interactive, an enhanced version of the broadcast show. On CSI Interactive, the TV screen is divided into two parts: next to the main action of the episode, a narrow portion of the screen shows supplementary footage that relates to what is happening in the story. Herigstad showed a clip from CSI Interactive that uses different types of enhanced content. One example was a "lingering pictorial remnant" of an interesting detail that was shown too quickly in the regular episode, such as a fingerprint. Extra content can also enhance setting. In one scene, an investigator describes the location of a murder, while the supplementary screen displays the blueprints of the house. With "multiple camera view," the audience can view a scene from other angles, or from the perspective of other characters. With multiple screens, viewers can do "eye editorial," or choose what they want to look at, processing the story in a different way. Another method for interacting with programming is used by Turner Classic Movies. In a multi-player game, viewers pretend to be movie moguls by making virtual contracts with actors, and monitoring how their movies fare in ratings. The goal is to sign the stars that draw the most ratings. Such interactive applications can be a new way to promote shows. To conclude, Herigstad showed a clip from Sci-Fi Channel's miniseries Battlestar Galactica (2003), which had a gaming component embedded in the show. Using a Microsoft X-Box, the viewer could participate in a battle sequence by playing a shooting game as the events of the TV series unfold in the background. How the player performs in the game corresponds to what happens in the story. Integrating gaming elements with television is a further attempt at creating an immersive experience. Discussion MATTHEW WEISE, CMS graduate student: In CSI Interactive, did the creators of the show conceive the extra content? There are artistic reasons for what writers choose to show on screen. How does the additional material affect the authorship and vision of the show? HERIGSTAD: CSI Interactive was a very experimental project. We came in after the episode was made and added material that we invented. Since CSI is about forensics, we focused on supplying technical information. For storyline information, we would work with the writers. The type of enhanced content depends on the show, and what it is trying to achieve. IAN CONDRY, MIT Foreign Languages and Literature: What are the peer-to-peer possibilities of TV programming? Is there a movement towards allowing or preventing it? BERNOFF: Media companies want to control their content, so they are against file sharing. Service providers tend to be on both sides. A company like Comcast wants to sell broadband service, even though they know customers use it for sharing and downloading music. However, they wouldn't want people to download cable shows and cancel their cable service. Although TiVo makes it easy to skip over commercials, it is not interested in destroying the media business. It also has security features that limit the kind of file sharing it can do. ReplayTV produced a rival system that allowed viewers to automatically skip commercials (as opposed to fast-forwarding through them), and send recorded programming to other users. As a result, the company was sued by the networks, and has since agreed to remove those features. HENRY JENKINS, CMS director: In the examples of interactive TV, there are certain assumptions being made about viewership. The extra details in CSI Interactive pull you deeper into the world of the story, making it more real. In the Turner Classic Movies game, you are pulled out of the world of the films, and made aware of other things like ratings and promotion. Is there a model for designing interactive programming? HERIGSTAD: The model for what we are doing is extended media. We think that most of the people who watch CSI Interactive would have already seen the regular broadcast, and wanted to deepen their experience of it. Turner Classic Movies also assumes that its core audience has seen the movies before, so their game extends the life of the media. It is similar to how people buy DVDs for the added material. BERNOFF: I think the problem with interactive television is not the technology, but the lack of a model for storytelling. People are used to interacting with games and watching linear stories. Most attempts to combine the two have either been linear experiences with a little interaction, or something so radical that audiences are not ready for it. There has been no successful model. In the television industry, success is determined by measuring viewership. Nielsen has a monopoly over that metering, and is now trying to monitor video recording devices and on-demand systems, which is already a major step for them. If faced with something as revolutionary as interactive TV, where you cannot quantify the level of attention people pay to it, Nielsen will not be able to measure it. Unless they can, interactive TV will not be widely used or successful.

HERIGSTAD: I want to emphasize that what we do is highly experimental. However, there is a need for new ways of branding and advertising, because people are skipping commercials. Enhanced commercials are no longer interstitial, but embedded in games or stories. We are exploring ways to create spaces that would formally be called advertising, but are noninvasive, and could actually add value to the experience. Once TV becomes less linear and more on-demand, viewers will have a space that is more open for branded messages. MARK LLOYD, MIT Martin Luther King Jr. Visiting Scholar: What is happening in other countries where there is a much stronger media environment for public service, such as in the UK with the BBC? BERNOFF: In the U.S., the power is in the hands of major cable operators and media companies. In contrast, the BBC is the most powerful media force in the UK, and they are helping to develop standards that work across systems. The British Sky Broadcasting (B Sky B) system, which has interactive capabilities, is also well established and growing. SARAH

SMITH: It seems that what you are trying to do with interactive

TV is already being done on the Internet to some degree. Will

interactive TV bypass the networks and go straight to broadband

on the web? HENRY JENKINS: Despite being so user-friendly and having the top functions users desire, why did TiVo have such a relatively slow adoption rate? BERNOFF: When TiVo first came out, people weren't exactly sure what it did, and it was hard to set up. Now, they are being built into cable and satellite boxes. Out of 3.5 million DVR households, about 1.3 million are TiVos - half of which are DirectTV boxes, and the other half stand alone units. The EchoStar Dish PVR, which has the same basic features as TiVo, has the largest market share. Comcast and others will soon launch their own digital recorders. JONATHAN WILLIAMS: Since television is so powerful in shaping a culture, do you see an ethical dimension to any of the technological choices you make? BERNOFF: I only analyze what is happening in the industry, but I do have some influence on media executives. Ethics is not the first thing they worry about, but they are conscious of the role TV plays in society. Over the decades, there has been a steady shift away from a common media experience to more fragmented viewing times and channels. The question of who has real influence in this environment is important. I think the companies like Comcast, who control interfaces and access to content, are more important than the content creators like Disney. Comcast's recent bid to buy Disney reflects this. MATTHEW WEISE: Since viewers don't want to watch commercials, advertising that is embedded into interfaces or content seems bound for failure. Is trying to find another ad model for television worthwhile? BERNOFF: I spend a lot of time looking at that question. Digital video recorders do have the potential for destroying the advertising model. Statistics say that four years from now, half the population will have video-on-demand or DVRs. People with DVRs watch recorded programming 75% of the time, and skip about half the ads. After doing the math, you have 30% of the population watching recorded material, and 20% of all ads are being skipped. Most companies we surveyed say they will reduce spending for commercials by up to 20%, which is significant. Still, executives are convinced that advertising and media will continue to be married somehow, and we need to look for more innovative models. Many are interested in targeted ads aimed at individual households, which will be possible with video-on-demand. But that will depend on two things: precise metering and a means of finding out the demographics of a household. Audiocast In order to listen to the archived audiocast, you can install RealOne Player. A free download is available at http://www.real.com/realone/index.html.

|

|||