| who

owns research and teaching? Thursday, Sept. 19, 2002 5:00-7:00 p.m. Bartos Theater MIT Media Lab 20 Ames Street |

|||||

|

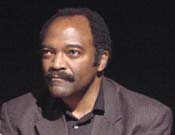

This fall the MIT Communications Forum will sponsor three linked conversations about changing notions of ownership, markets, invention and property. The first will center on universities and on contested or emerging views of research and teaching. Who “owns” scientific data bases? Should research results be private and for sale? Are current definitions and emerging ground rules for patents comparable to recent changes in copyright law? Topics will include MIT initiatives in Open Course Ware and other non-commercial projects. The second Forum examines Creativity/Markets/Copyright. The final Forum explores Copyright and Culture. Harold (Hal) Abelson is a founding director of Creative Commons and was instrumental in MIT's open courseware initiative. Abelson is Class of 1922 Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at MIT and a Fellow of the IEEE. Ann Wolpert is Director of MIT Libraries and a member of the MIT Committee on Copyright and Patents. She also chairs the management board of the MIT Press and the board of directors of Technology Review, Inc., which publishes Technology Review. Respondent: Mark Lloyd is the Martin Luther King Visiting Professor at MIT and is the executive director of the Civil Rights Forum on Communications Policy where he works with leaders in the civil rights and public interest community to influence federal, state, and local communications policy. He worked on communications and arts policy in the Clinton Administration, co-founded the Civil Rights Telecommunications Forum in 1997, served as national coordinator of the People for Better TV campaign, and chaired the board of directors of the Independent Television Service. [This is an edited summary, not a verbatim transcript.] DAVID THORBURN, director of the MIT Communications Forum, introduced this Forum as the first of three devoted to changing notions of intellectual property and copyright. Tonight's Forum will center on these matters as they touch upon research and teaching. Thorburn remarked that by ushering in new modes of capturing, sharing and creating data, the digital age has raised fundamental problems for traditional conceptions of creativity and the ownership of intellectual work. The purpose of tonight's discussion is not to solve such complex problems but to participate in a broad national and international conversation on these subjects.

HAL ABELSON quickly distilled his argument: "The main point is that this whole discourse that we get sucked into about copyright and who owns what is, I think, destructive to universities." The mission of universities --that of handing down the values of civilization -- is, "fundamentally hostile to the values of the information economy." In recent years, "Universities have become the target of a massive fraud that says that a university is some kind of factory for some kind of thing called content." He noted that universities have been tempted by the enormous financial promise of a paradigm that runs counter to their mission. To illustrate this point, he showed a recent statement from the University of Southern California, made in response to threats from the Motion Picture Industry and Music Industry about peer-to-peer file swapping. The statement explained that USC's purpose is "to promote and foster creation of IP." Such a rationale for an institution of research and learning, Abelson said, narrows and commodifies research, much of which must be free of commercial intent. " It's not that this is wrong, it's just that you look at this and you say, I don't want to think about things that way." Abelson then discussed a statement from the University of Chicago which asserted that since knowledge-building at the university is a collective enterprise, the university formally declares its ownership of all the IP created by its faculty on its premises. This position, too, seems dangerous to Abelson: "We fall into a trap when we conflate what we call academic freedom with some notion of property rights." Abelson recommended Corinne Mc Sherry's book Who Owns Academic Work (2001), which he described as a discourse analysis of the thinking about IP ownership in universities. "What goes on in the university is not hospitably thought of in terms of property rights," he said. Citing the inappropriateness of legal discourse in an academic context, Abelson said "There is a difference between copyright infringement and plagiarism." "The problem of getting into this legal stuff is that IP law frames everything in terms of rights and ownership. The way you fight lawyers is with more lawyers. The second law of thermodynamics where there is the eventual heat death of the world can be applied here. I worry about the legal and intellectual property death of the academy." The morning of the Forum, Abelson had come upon a "little vision" of the intellectual property death of the academy. While browsing the web, Abelson discovered a recent note to faculty from the Office of General Counsel at the University of Texas. The letter explains that when students take notes at a lecture, they are in effect creating a derivative work. The letter encourages faculty to consider asking students to sign a license to take notes in class from a lecture, explaining that " A limited license to take notes could be very important to protecting the intellectual content of lecture materials." (UT, August 2001). The general counsel for the University of Texas had even prepared a template for such a license for the faculty's convenience. Abelson jokingly suggested that MIT should offer a differential tuition; one allowing you to sit in class and another allowing you to sit in class and actually use what you learn. Abelson regretted that the first half of his talk had been inevitably depressing and devoted the second half to what he felt were positive developments in knowledge-sharing and digital technology. He cited MIT's Open CourseWare project, to be launched September 30 of this year, as an example of how MIT understands the opportunities of the Internet. Open CourseWare will make available on the Internet, not an MIT education, but "the stuff from which we make an MIT education." He described Open CourseWare as an act of leadership by MIT, an effort to make the world beyond the university more hospitable to the values of the academy. "The wonderful thing about information is that it increases in value the more people use it. In the parlance of the economists, it is anti-rivalrous." The notion that MIT chooses to give away its course materials challenges the discourse about ownership and control of information. A second initiative in which Abelson is actively involved is Creative Commons. The establish a context for understanding the Creative Commons project Abelson offered a brief review of copyright law. "I have compressed copyright law onto one slide, Abelson said. Copyright, according to this distillation:

"The most ridiculous thing about copyright," Abelson said, "is that people are talking as if it is reasonable to ask human beings to understand it. And that's a very serious comment… Copyright law was made in a world where there were large publishers who hired experts who were copyright lawyers and the copyright law was made for the experts. It is not designed for ordinary people to use." The framework of law makes it difficult to share creative and intellectual work. "All rights reserved" may not always be the best option for an author or his/her work. Ever since copyright became automatic in 1978, it has been "surprisingly hard" for an author to opt for something other than "all rights reserved." To declare something "no rights reserved" or to abandon works to the public domain is almost impossible to do in legal terms. Controlled sharing, "a reasonable thing that universities might want" is excessively complicated. "You have to hire a slew of lawyers to turn that easy expression into legal language," Abelson said. Addressing these and related difficulties, Creative Commons has created a commons deed defining four categories for licensing or authorizing the use of creative and intellectual work:

Copyright

lawyers have worked carefully on the commons deed to assure

that it is legally binding. Code and documents are now being

developed, Abelson said, that some day will allow people to

search Google for works that use a particular Creative Commons

deed.

She identified

two key aspects of the new copyright protection regime. The

first is that it creates a monopoly right in a tangible medium

of expression. The remarkable difference in longevity of copyright

versus patent creates an enormous potential for financial gain

for copyright holders. Wolpert reminded the audience that US

copyright law currently excludes from ownership ideas, data

and other "raw" knowledge. Big publishers and entertainment companies who have an interest in controlling digital information have taken their case to those who write laws both in the US and internationally. As a result, the terms by which the public may gain access to academic materials are set by publishers and entertainment companies. As publishers and entertainment companies' interest in copyright grows, so do the penalties for copyright infringement. "The Digital Millennial Copyright Act introduced the idea of felony into copyright," Wolpert said. Copyright infringement had been understood as a civil disagreement, now you can go to jail or be fined for what has been redefined as a serious crime. One instance of entertainment industry's influence over copyright has been in the extension of the copyright term from 50 to 70 years (plus author's lifetime), result of lobbying by the Walt Disney corporation to protect the copyright of Mickey Mouse. In the international sphere, the European Union has created new controls over such items as formulae and data, which cannot currently be protected in the US. Because of international treaties, the US is under pressure to implement those changes as well. This environment is creating new challenges for academics. In the digital environment, if you take your own published work (having relinquished the copyright to a publisher) and put it up on the Web for anyone to use, you are violating the law. "It is a very different environment that most faculty and others are generally oblivious to," Wolpert noted. Academic publishers do not provide permission for their authors to use their own published material as freely as one might expect. In the Open Courseware project, 80% of requested permissions were denied. Wolpert praised a recent mission statement from MIT. "There is nothing here about intellectual property, " she noted "and there is no assumption that we will make money." An open environment in which ideas, images and texts are easily available is critical for the survival of academy, said Wolpert. "We know that the best students come from everywhere and they don't all have money." Wolpert imagined a scenario in which a student would have to decide between having lunch or accessing a costly text on-line. Intellectual spontaneity, according to Wolpert, would be impossible in an environment where everything is locked down. MIT believes information should remain open and free. Wolpert believes the academy needs new tools to deal with this environment. Faculty and students need to have a reasonable ability to use intellectual materials and to learn and exchange knowledge without fear of criminal prosecution. "Making the use of someone else's material a felony means that something is seriously wrong with the law," Wolpert said. She remarked that the cost of permissions and fees for reprinting or reproduction are horrific in a not-for-profit environment such as the academy. Wolpert briefly discussed two MIT responses to the challenges posed by copyright controls and emerging digital media. The first is Open Courseware, which has been seriously hampered by existing copyright law. As a single example, Wolpert noted "It turns out that it is easier to take another photo than to trace the owner of the original photo." The act of putting MIT course materials on the web, it turns out, involves a huge problem "in terms of what you can and cannot do in the intellectual regimes in which we currently operate." The second initiative is "D space," a collaboration between Hewlett Packard and MIT libraries. Wolpert thinks of it as an "enormous digital filing cabinet." It is a secure repository for digital works of all kinds. D Space serves faculty who to store course materials that they wish to share with faculty and students.

MARK LLOYD: "There are fewer questions more important to the academy today than who owns ideas." He noted that the founders had limited copyright to 14 years, following British copyright law of the time. Copyright law did not expand substantially in the U.S. until the birth of the giant corporation. The current status of copyright law, Lloyd said, is far from the intention of the founders. Lloyd said

the issue of copyright and the control of ideas has low visibility

in the major media. Most Americans are unaware The issue of intellectual property "gives the University an incredible opportunity to be relevant to most Americans," he said. MIT is in a particularly strong position to provide leadership in this area, and ought to enlist both Massachusetts' senators to educate the public and work in Congress to change the law. Lloyd said, "The copyright law has been distorted because people we voted for voted to change it." Lloyd encouraged the MIT community to work actively on this issue. "If the law has been changed once, it can be changed back." Q&A NADYA DIREKOVA, an MIT graduate student, asked, "Who owns my thesis?" WOLPERT answered, "You own it but MIT extracts a license to reproduce it." An audience member asked "If MIT has a monopoly on making updates to the courseware, isn't there the danger that they will shift away from some particular courseware and maybe shift to a whole different set of materials?" WOLPERT replied that one might think of Open Courseware as way of publishing faculty manuscripts. The Open Courseware's publishing process standardizes faculty work in terms of design and formatting, but makes no substantive alteration to it. "The intellectual control of Open Courseware remains in the hands of faculty," she said. Another audience member said he saw some parallels between Open Courseware and the Open Sourceware movement. He said that in the ideal case he'd like to see a model that addresses the issue of derivative works. "Is one of the goals to take a lot of these licensed and copyright materials and make new open versions of these classes so that they can be freely shared around the world so that universities don't have to license these over and over again and so that basic knowledge can be open?" ABELSON replied, referring to derivative works, "As far as I know, no one's decided that yet. . . . One possibility is that you leave it to individual contributors to decide whether they allow derivative works, though that's a little messy. I would be very much in favor of allowing derivative works on the model of free software." WOLPERT added that she believes that a lot of these are not legal issues. They they are questions that faculty must decide among themselves. They must define standards of behavior in the digital environment for works that are born and managed digitally." PHILIP TAN, MIT graduate student, asked "What happens when a syllabus in Open Courseware includes works that MIT really doesn't want the public to see -- for example if I come up with word problems that are basically racist? Or really poor fact checking? The things that MIT does not want to be associated with? Is MIT obliged to put them up?" WOLPERT laughingly said that MIT hadn't yet come to that bridge, let alone crossed it. --compiled by Heather Miller, CMS 2003 |