Costa Rica

Cerro Chirripo - 12,533ft

Eric and Matthew Gilbertson

Date: March 28, 2013

More pictures here: http://mitoc.mit.edu/gallery/main.php?g2_itemId=407937

Cerro Chirripó (12,533 ft)– Highest Point in Costa Rica

March 28-29, 2013

3:53pm-12:21am (8h28m)

24.2 miles

9,100ft elevation gain

§§§§§§§§§§§§§

“Hola señor, queremos subir Cerro Chirripó y nos gustaría comprar un permiso.” (“Hello sir, we plan to climb Cerro Chirripó and we’d like to buy a permit”), Eric said to the ranger sitting behind the counter. We had just walked into the ranger station at the base of Cerro Chirripó, the highest point in Costa Rica.

“¿Ok, qué día quieres subir?” (“Ok, which day would you like to climb?”), the ranger asked.

Eric paused for just a moment. This was a question that we had been expecting and whose answer we had carefully contemplated and crafted over the past couple of weeks. Our answer could take one of two forms. We could either answer truthfully, which would be certain to draw skepticism from the ranger, and could quite possibly unravel our entire plan. Or, we could give another answer that was, ahem, a slightly different version of the truth, but would elicit a more favorable reaction from the ranger and enable us to execute our plan.

“Mañana,” Eric said, “nos gustaría subir en un día de mañana.” (“We would like to climb in one day tomorrow.”)

“Ok, bueno, es posible subir el Cerro Chirripó en un día, pero hay que empezar a caminar muy temprano, como a las 4 o 5 de la mañana.” (“Ok, good, it is possible to climb Cerro Chirripó in one day, but you must start hiking very early, like 4 or 5 in the morning”), the ranger answered. “Es 8,000 colones por persona para el permiso.” (“It is 8000 colones per person for the permit.”) (~$15 USD).

Eric and I both breathed a huge mental sigh of relief and forked over the permit fee. Things were proceeding according to plan. No answers such as “sorry, the permits are sold out” or “no, you can’t climb it in one day” – those were the answers that we had feared. From the ranger’s response, it sounded like it was relatively routine for people to climb it in a day, so we thankfully didn’t arouse any suspicion. However, we would not be climbing Chirripó tomorrow. The climb would begin this afternoon.

With permits in hand, and after a warm “gracias,” we strode confidently out of the ranger station, hopped into our RAV4 with Amanda and her mom, and continued up the rugged gravel road towards the Chirripó trailhead.

§§§§§§§§§§§§

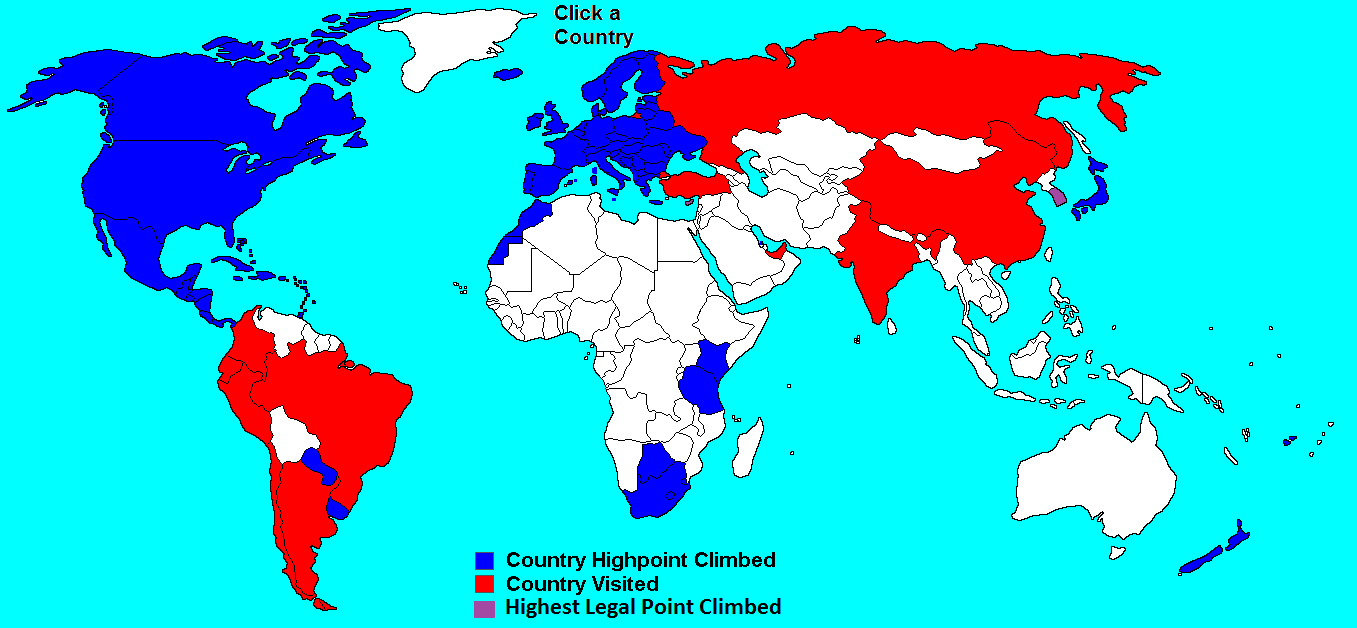

COUNTRY HIGH POINT #5

We were in Central America for nine days of country highpointing, and had just arrived in San Jose, Costa Rica at 9:35am after successful ascents of Volcán Tajumulco (Guatemala), Cerro Las Minas (Honduras), Cerro Mogotón (Nicaragua), and Cerro El Pital (El Salvador) over the past seven days. Next on the menu was Costa Rica’s Cerro Chirripó and Panama’s Volcán Barú – in total, the trip would be a six-mountain “hexafecta” of country highpoints.

We were hoping for a bit of a respite with Cerro Chirripó. The road trip through Guatemala/Nicaragua/El Salvador/Honduras had been, at times, harrowing, thrilling, and frustrating. There had been bribes, border crossings, inspections, car problems, heavily-armed police checkpoints, rush hour gridlock, livestock in the road, and of course the occasional unmarked section of road where half the pavement has fallen off the cliff. Oh, and not to mention we did climb some mountains along the way, but that’s more of a footnote because the hikes were all much easier than the driving. As we looked to Cerro Chirripó, with its 24 miles of hiking (roundtrip) and >9,000 ft elevation gain, we eagerly anticipated more time spent hiking rather than sitting in the car.

We passed through Costa Rican customs and rendezvoused with Amanda and her mom, who had arrived in San Jose the previous day and had toured around the city. Next stop was Europcar to pick up our RAV4 rental SUV. Our friend Adam Rosenfield, who climbed Chirripó in Dec 2011, had advised us that the road to the trailhead was rough, so we opted for the heavy-duty SUV to minimize any chance that our vehicle would be a limiting factor to our success.

Compared with driving in Guatemala, driving in Costa Rica was a breath of fresh air. Here in San Jose, there were road signs, traffic lights, clean streets, occasional painted lane lines, and a general orderliness of things that made you almost feel as if you were driving in the US.

Google Maps estimated driving time of 3 hours from Juan Santamaria International Airport to the Chirripó ranger station, and the way the roads were looking, we felt that it would be an accurate estimate. (For comparison, Google’s driving time estimates in Guatemala and Honduras turned out to be half of the actual times.) The first part of our journey took us through the mountains, and around el Cerro de la Muerte (Mountain of Death). We drove through the clouds and lush jungle and eventually reached an elevation of 11,000ft, just 1,500ft shorter than Chirripó! But thankfully, the highest point in Costa Rica is not attainable by car.

By 2pm, we had reached San Isidro Del General, and turned off the main highway, following signs for Parque Nacional Cerro Chirripó. Fifteen additional minutes of driving would bring us to the ranger station, the biggest question mark in our plan.

THE IMPOSSIBLE ITINERARY

As it turned out, more hours were spent planning our ascent of Cerro Chirripó than in executing it. Trip planning had begun back in August 2012, nearly seven months earlier, when we had initially considered heading down to Central America with our brother Jacob. We had ended up driving to Labrador and Newfoundland instead, but not before making a few Skype calls to car rental agencies across Central America to gather information. From our road trips into Atlantic Canada, we had grown accustomed to the idea of renting a car and seamlessly crossing international borders. Surely, we could rent a car somewhere in Central America and drive through all the other countries?

As we began to investigate, it became apparent that cross-border driving with rental cars was not a routine thing in that area of the world. Most of the rental agencies we looked up online said either “cross-border driving is not permitted” or nothing at all. We Skyped or emailed those agencies that didn’t specify on their website, and finally discovered that Alamo in Guatemala City allows cross-border driving into El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua. After extensive research into rental agencies in airports across Central America, this appeared to be the only agency that permited entry into more than two other countries. So the first half of our journey was decided; we would rent a car in Guatemala City and drive to El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua.

What about Costa Rica and Panama? I contacted numerous rental agencies across Costa Rica and learned that no agency allowed cross-border traffic into Nicaragua or Panama, the two bordering countries. The reason is that the government apparently mandates that all rental agencies in the country use the same insurance policy, and that policy does not cover cars outside of Costa Rica. If you really want to drive from Costa Rica into Panama, some agencies do offer to meet you at the border, and you walk across from one side to the other and hop in a different waiting rental vehicle. I inquired about this possibility, but the few agencies that did offer this option charged an arm and a leg for it. More importantly, though, the chances of a plan like that actually working out seemed pretty slim. We hadn’t been too impressed with the reliability of rental agencies in the Caribbean on our previous trips and wouldn’t want to be stuck at a border crossing with no transportation.

As we contemplated our options, we tried to estimate how much time we would actually need in Costa Rica. Our friend (and fellow highpointer) Adam Rosenfield had summitted Chirripó back in December 2011, and in his excellent trip report, detailed the red tape imposed by the Costa Rican government on a climb of Cerro Chirripó.

It turns out that most people who climb Chirripó take two or three days to cover the 24.2 miles (roundtrip) and 9,100ft of elevation gain, and stay at the Base Crestones Hut or other huts along the way. Unfortunately, the huts are often fully booked, which makes things complicated. But not easily defeated, Adam found semi-loophole in the rules: what if you just hike it in one day? And that’s exactly what he did. Inspired by Adam’s feat, we planned to hike it in a single day ourselves.

We looked at the map and saw that Cerro Chirripó is located only about 80 miles west of Panama’s Volcán Barú. It seemed that surely there ought to be some way to proceed directly from Chirripó to Barú’s nearby town of David without needing to drive all the way back west to San Jose. Perhaps we could take a bus?

We looked into bus routes and schedules and it looked like the bus times would all work out. We would take a bus from San Jose to the Cerro Chirripó trailhead, climb Chirripó at night, bus the next day to the Panama border, and then bus from Panama border to Boquete, the trailhead town for Volcán Barú. The plan would require us to climb Chirripó at night, which wasn’t ideal but was still feasible, and thus it seemed that the plan would work out. I figured that we could just purchase the bus tickets when we boarded the buses. We assumed that the trip planning was finished.

A week before the trip, Amanda asked me if I knew any details about how much the bus tickets cost, or if we can buy them in advance. So I decided to do a little more research. I came across one website called A Safe Passage, a service that can purchase your bus tickets in advance for a fee. As I browsed the website, some text in bold caught my eye: “Those traveling on a one-way ticket [flight] need proof of an outbound flight or onward bus ticket in order to board their flight and enter the country.” I immediately froze. Wait, we’re flying into Costa Rica on a one-way ticket, and leaving via bus, so this applies to us!

Well no big deal, I thought, we can just have A Safe Passage purchase the tickets for us, then we’ll fulfill the “proof of onward journey” requirement. At least we didn’t find that out the hard way at the immigration booth at the San Jose airport. I contacted the company and began to correspond with a gentleman named John. And this is when our plan began to unravel.

We would need to purchase three bus tickets in all: 1) a ticket from San Jose to San Isidro (near the Chirripó trailhead) on Thursday; 2) a ticket from San Isidro to Paso Canoas (Panama/CR border) on Friday; and 3) a ticket from Paso Canoas to David (Panama) on Friday. John emailed back and said that he would be able to get #1 and #3 for us, but unfortunately #2 wouldn’t be available because that particular Friday is Good Friday, and the buses don’t run! In fact, he said, that week “is Semana Santa and some buses are already sold out.”

I did some research and learned that Good Friday is the holiest day of the year in Central America and is during Semana Santa (Holy Week) which ends on Easter Sunday. Taking a bus on Good Friday in Central America would basically be like taking a bus on Christmas Day in the US – the availability is understandably limited. But that really threw a wrench in our plan. How are we going to get from San Isidro to the Panama border on Good Friday? Could we change our schedule?

Unfortunately, we were pretty much constrained to only one day in Costa Rica; we had already stretched our vacation time thin and didn’t want to take off any more days than absolutely necessary. It would be very good if we could fit Costa Rica into one day, and we were determined to find some way to make it work out.

So next, I looked into hiring a taxi to bring us from San Isidro to the Panama border. John suggested that finding a taxi would be difficult, and I could find very little information online about taxi companies. So, I began to backtrack. Could we do a one way car rental? We’d pick up the car in San Jose, then drop it off at the Panama border? I Skyped with a few car rental agencies and they either wouldn’t do a pickup on Good Friday, or charged more than $200 for the service. Our options were running slim. One helpful representative said that his cousin was a taxi driver, and he’d ask him if he could give us a ride to the border. A few days later, he responded that his cousin would not drive on Good Friday, and we’d be hard pressed to find anyone who would. We were running out of options.

Desperate, I called up the US Embassy in San Jose, Costa Rican consulates in the US, as well as Customs and Immigration at the San Jose International Airport, and asked if telling the immigration officer “we’re going to take a taxi across the border” would count as sufficient proof of onward journey. Out of the eight officials I spoke with or emailed, four of them said it would be sufficient, two said it would not, and two didn’t know. That meant that there was enough uncertainty that we couldn’t guarantee success in clearing customs if we presented that story.

So, taxis were out, buses were out, a one-way car rental would be expensive and we couldn’t count on a pickup. We thought briefly about skipping either Chirripó or Barú. But skipping one mountain would mean another trip down to Central America for just one mountain, which didn’t seem to make sense. If we’re flying down there, we thought, we’ve got to make it count.

Then, we finally had a breakthrough. Amanda’s mom discovered that Air Panama flies from San Jose to David (Panama) two days of the week, one of which is Friday. The flights weren’t too expensive, so we quickly purchased tickets, only a few days before the trip. So the plan was finally set: we’d fly into San Jose on Thursday morning, show the immigration officer our flight itinerary leaving San Jose the next day (26 hours later) for “proof of onward journey,” meet Amanda and her mom in the airport, and rent a car and drive to the Chirripó trailhead. Eric and I would climb Chirripó at night while Amanda and her mom slept at a trailhead hotel. In the morning, we’d drive back to San Jose and fly out to Panama at 11:45am. It didn’t sound like we’d get any sleep in Costa Rica, but at least we’d be able to climb Chirripó.

EXECUTING THE PLAN

As we neared the Chirripó ranger station, we reviewed the plan. Since Eric spoke Spanish, he would speak with the ranger as I stood nearby. Amanda would jump in if any translation help was needed. We would be climbing the mountain at night, but we wouldn’t tell that to the ranger. Perhaps our plan was perfectly OK, perhaps the ranger would be totally OK with it, but what if he wasn’t? In the end, we played it safe and told him we’d be climbing tomorrow, and he nodded with approval. In less than five minutes, we had our permits and continued up the steep, bumpy road to the trailhead. We hadn’t started climbing the mountain yet, but we relaxed with the satisfaction that our plan was falling into place.

By 3pm, we had reached Hotel Uran, located within 200 ft of the Chirripó Trailhead. Amanda and her mom would be staying there tonight. We had heard about Hotel Uran from Adam’s trip report, and it was perfect because it not only provided a nice, cheap (~$15/person) place to stay close to the trailhead, but also gave us an authentic address that we could fill in on the immigration card when we landed in San Jose.

Amanda and her mom had come prepared with some delicious pre-hike food, which we voraciously scarfed down at the hotel. They graciously gave me and Eric some granola bars, cookies, and crackers that they had brought down from the States. The four of us started hiking together under the hot, dry afternoon sun. “Well if it stays this clear tonight, maybe we’ll be able to see both oceans from the top!” Eric said optimistically. Let’s just say the weather at the summit turned out to be vastly different than the weather at the trailhead.

Each of the twenty kilometers to the summit is marked by a beautiful engraved plastic sign, and each has a nickname like “El Quetzal” or “El Jilguero” (“the goldfinch”). Amanda and her mom accompanied us to KM1, “Los Monos” (“the monkeys”), and bid us farewell. “What time do you think you’ll be back?” Amanda asked.

“It’s hard to say.” I told her. “Maybe 1 or 2 am? We’ll have to start driving back to San Jose at 5am, so we’ll want to wake up at 4:30am. It’s 4:15pm right now, and 24 miles total, and we average 3mph, so maybe 8 hours from now – that’d be 12:15am?”

“You guys are gonna be tired,” she said, “You better eat all that food! And here’s the secret knocking-on-our-hotel-door-for-entrance code when you come back! And be safe!”

Eric and I waved goodbye and started jogging. We figured 8 hours would be a pretty reasonable estimate, but hoped it would be less so we could get some sleep at the hotel before the drive back to San Jose. Although we had gotten some sleep in the Guatemala City hostel the previous night, the past week of stressed driving and long days had drained the tank of sleep and we had not yet been able to refill it. But the bright sunshine and excitement of the climb ahead of us kept us alert, and we made good time up the steep, rugged trail.

INTO THE DARKNESS

We reached the (unmanned) entrance to Cerro Chirripó National Park at 5pm, about 7 hours before our permit actually became valid. We had already passed a decent number of hikers on their way down, but no obvious rangers yet, so we weren’t too concerned. If any ranger made a fuss about our permit, we’d just tell them that we decided to get an ultra-early start in order to make sure that we had enough time to reach the summit in the daylight. Instead of starting at 3 or 4am as suggested, we just decided to start at 4pm for an “ultra-alpine” start.

The sun set at 5:45pm and we busted out the headlamps 45 minutes later. The climb was a sustained 12% grade and we took off our shirts to help stay cool. Several kilometers later, we spotted a magnificent hut just around the corner. It would have made a spectacular place to sleep, but alas, we had neither the time nor the supplies to camp there, so we would have to pass it up. In an effort to be as stealthy as possible, and not attract any attention, we switched off our headlamps and tiptoed by the shelter, guided by starlight. It appeared that nobody was inside, but we slinked by quickly nonetheless.

After a few more hours of climbing, we crested a ridge and the wind began to pick up. The lights of San Gerardo and San Isidro twinkled miles below us in the valley, but it was difficult to discern the landscape ahead. It appeared that we were walking towards a giant cloud, and indeed we could see faint flashes of lightning in the distance. “Well, we’ll just have to make it to the top before that thunderstorm gets here,” Eric said.

At about 7:45pm we reached the main hut, called Base Crestones. It was an impressive complex of buildings, complete with electricity and, according to Adam R, even Wi-Fi. A cold drizzle began to blow on us, making the hut look even cozier. But we had to resist the temptation to enter the hut; there were certainly rangers inside who would likely implore us to stop hiking if they caught us. So we switched once again into stealth mode, and snuck past the hut incognito.

At this point, the trees began to thin out, the trail became rockier, and the cold, steady wind-driven drizzle intensified. We could see that we were now hiking up into a cloud; this was the end of the clear, pleasant weather that we had enjoyed thus far. In the darkness, the trail became a bit trickier to follow, but luckily we had the GPS track from another person’s ascent, so we were never off-trail for long. As we climbed, the temperature dropped and the drizzle intensified, and before long the conditions became miserable: temps in the upper 40Fs, pouring rain, 20-30mph winds, and a slippery, steep, rocky trail. Not to mention, it was dark.

We picked up the pace in an effort to increase our heat production and reduce our time spent in misery. At times, it was almost as bad as my ascent of Montanha do Pico in the Azores during Hurricane Nadine, except here we were climbing without the aid of daylight.

THREE MINUTES ON THE SUMMIT

“Just a quarter mile line-of-sight to the summit!” I yelled to Eric over the roar of the wind.

“Awesome!” he said. “Let’s tag it and get out of here!”

We turned a corner and were faced with a seemingly vertical wall of rock. It was difficult to determine the nature of the obstacle before us, but we knew that it couldn’t be too sustained if the summit was that close. We scrambled up the rocks and pushed on into the cold, dark, wind-driven downpour. Finally, at 8:48pm on March 28th, 2013, we clambered over the last few rocks and were on the summit of Costa Rica.

“Well so much for being able to see the Atlantic and Pacific,” I yelled to Eric.

“Yeah, maybe we’ll have better luck tomorrow night on Barú,” Eric replied.

“We’ve got time for just a couple photos before my hands go numb,” I said.

We hastily snapped a few pictures in front of the summit sign. “Ok, time to go,” I said.

“No, we’ve got to sign the summit register” Eric shouted. Eric opened up a rugged green steel box perched near the summit sign and grabbed the pen. He could barely hold it, but as he pinned down the other pages to keep them from flapping in the driving rainstorm, he managed to scrawl into the notebook our names and the current date and time. “Ok, now it’s official,” he said. “We’re outta here.”

“All those days of effort spent planning this trip and all that traveling for just three minutes on the summit,” I said, “but it’s absolutely worth it.”

STEALTH MODE

Relieved that we had accomplished our goal, but mindful that we still had 12 miles of hiking and 9,000ft of descent, we carefully descended the slippery summit rocks. Forty minutes later, we were back at the hut and the rain had slackened. “Well I don’t think we really need to be stealthy anymore,” I said to Eric. “Even if someone catches us and is unhappy, they can’t take away the fact that we’ve been to the summit. We’ve just got ten hours to get from here back to the San Jose airport.”

“Well, we still ought to be stealthy,” Eric said.

We turned off our headlamps and tiptoed by Base Crestones. All the lights were off and everyone was likely asleep inside, preparing for an early morning climb. Even if there’s no need to be stealthy, it’s still more fun to act that way.

As we continued to descend, we had a chance to dry out our soaked clothes. We had brought rain jackets, but had foolishly allowed our base layers to get drenched before thinking about putting on the waterproof shells. But thankfully, the temperature was forgiving, and it wasn’t a big deal. Around KM4, we were a bit spooked to see a ten person group ascending silently in the darkness. Hopefully they had brought a headlamp, we thought, because they’re going to need it higher up. We guessed that they were probably headed up to see the sunrise, and must have started around 10pm. We said “hola” as they passed by.

I glanced down at my watch. “It’s midnight,” I said to Eric, “we didn’t quite beat eight hours.”

“Well that’s OK,” he said, “I think we’ll still make it in a respectable time.”

We made it back to the trailhead at 12:21am, for a total time of 8h28m. We were exhausted, and looked forward to a few hours of sleep. We triumphantly knocked on the door to Amanda and her mom’s hotel room, and went to sleep on the floor soon afterwards. We managed to get almost four hours of sleep before waking up at 4:30am for the 4-hour drive to San Jose.

ONWARDS TO PANAMA

We returned the rental car, breezed through security, and arrived at the gate for our flight to David (Panama) with two hours to spare. The plan was to fly to David, catch a taxi to Boquete, then start climbing Volcán Barú that night. As I lay on the floor, drifting in and out of sleep, Amanda graciously offered me a sub that she had bought at Subway, which I gobbled up voraciously. From coordinating the car rental to guaranteeing that we were always well-fed, Amanda and her mom had done everything they could to help make our climb possible and pleasant.

During our 24 hours in Costa Rica, we had spent 8.5 hours hiking, 8 hours in the car, 4 hours sleeping, 2 hours at the car rental agency, 1 hour eating, and a total of about thirty minutes chill-axing. Just another routine Spring Break highpointing trip.

Email us (matthewg@alum.mit.edu, egilbert@alum.mit.edu) for the GPX/GPS tracks of our ascent of Cerro Chirrpo.