| Vol.

XXVIII No.

5 May / June 2016 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

What I Learned as a Department Head

During 2007–2013 I was Head of the Physics Department at MIT. What I learned can be summarized by a quote from the 2015 Commencement address of Megan Smith ’86 ’88 SM: “Kindness is as important as knowledge.” Knowledge is important because understanding the work of my colleagues gives me their respect. Kindness, and its origin in caring, is necessary to give them – the department’s faculty, staff, postdocs, and students, as well as alumni, donors, and visitors – the respect they deserve. Respect and caring are, in my view, the two most important attributes a department head brings to leadership. But how does one go beyond platitudes? What does it mean for a department head to advance respect and caring?

Some background is needed before these questions can be answered. At MIT, academic departments and programs are the fundamental organizational unit for nearly all faculty and graduate students. When we say that MIT is decentralized, what we really mean is that academic departments and other work units are largely independent and have their own distinct cultures and climates.

I inherited the leadership of an excellent department. We were tied for the number one ranking in the US News and World Report Graduate School Rankings with a 4.9/5 rating. Faculty morale was generally good, especially among the senior male faculty. The department had initiated a highly effective fund-raising effort and had just completed a major building project. Interactions were largely collegial and effective management structures were in place. Faculty valued education and educational innovation, the department regularly graduated the largest numbers of Bachelors and Doctoral degrees in physics of any U.S. institution, and we had a good track record mentoring junior faculty to success. When I took the job, some people told me it could only go downhill!

I took the job because I cared deeply about the success of my colleagues and saw ways that it might be improved. In particular, our department had long struggled with efforts to increase the diversity of its students and faculty. Before assuming the leadership I met with a group that set my course in the role and beyond: female graduate students. They were recruited more effectively by our competitors, their morale was lower than that of other groups, and they were leaving the program at higher rates than men, despite being equally prepared on entry. The Graduate Women in Physics group gave me a focus on solving these problems by advising me, “You have to create a culture of caring in the department.”

Faculty are recruited and promoted on the basis of research accomplishments, and there is little direct reward for empathy. Faculty are generally solicitous of undergraduates but sometimes treat graduate students as if they are their employees. The distinction is striking when senior undergraduates and equally mature and prepared first-year graduate students are working in the same research group. The women were telling me what research confirms: graduate students succeed better when they are mentored with empathy.

Changing a department culture is not easy. The graduate women provided encouragement and help. Their determination showed me that I would be held accountable. I believe the combination of encouragement, help, and accountability are necessary for leaders to shift a departmental culture.

I will describe some of our efforts and the impact on the Physics Department shortly. First, this is why it matters today: all MIT departments are now being asked to make similar efforts. In December 2015, the Black Students’ Union asked every department head to make a statement valuing students’ well-being, and to commit to improvements in graduate student and faculty diversity. Since then, other groups have assembled recommendations, and Academic Council appointed a working group to make progress on them. MIT’s five School Deans requested a one-page set of best practices for department heads around diversity and inclusion. Here is my contribution:

Recommendations for Department Heads

Developing/supporting colleagues in your department may be one of your highest priorities: 3 Rs

- Recruitment – Build a strong, diverse organization.

Recruitment Retention Respectful Work Environment

Prepare: Join search/admissions chairs in at least one diversity/inclusion event/year, including an unconscious bias workshop, an ICEO event, the MIT Diversity Forum/Summit, or an event at your professional society. Become familiar with the terminology and issues. All search committee members (not just chairs) and all faculty involved in graduate student and postdoc selection should participate in an unconscious bias workshop.

Execute: Appoint a faculty or staff member, reporting to you, to advance diversity and inclusion within the department at all levels. Share expectations with untenured faculty (e.g., Advice for New Faculty). Undertake at least one departmental initiative to increase underrepresented groups entering the profession (e.g., participation in MSRP). Request faculty members to include their efforts in their Electronic Professional Record. Include them in your annual review process.

2. Retention – Continue your success in recruitment by furthering a positive work environment.

Prepare: Develop informal and formal listening opportunities (meetings, lunches, walk the hallways). Meet individually with every faculty member initially, and with groups at least annually (junior faculty, senior faculty, undergraduates, graduate students, postdocs, women students, minority students, administrative and support staff, research staff, lecturers). Ask the groups what they need.

Execute: Deliver on requests as best you can and/or be transparent with your plans. Accountability is essential. Meet with mentors of junior faculty to support their work; credit their work as departmental service; list a junior faculty’s mentors in your promotion/tenure cases; add mentors/mentees to the ePR.

3. Respectful work environment – Help your people thrive.

Prepare: Join other leaders in your department (associate head, graduate and undergraduate officers, division heads, etc.) in relevant workshops. Suggestions: MIT Conflict Management series, Crucial Conversations two-day workshop, and a department chair workshop offered by your professional society. Support graduate student REFS. Read the ICEO Report, the Women Faculty report for your school, and the Report on the Initiative for Faculty Race and Diversity.

Execute: Implement recommendations from Enhancing Department Climate: A Guide for Department Chairs (brochures available from ICEO). Cultivate respect and caring. State your department vision and values at your Website and in your talks to faculty, staff, and students. This may include a diversity statement similar to the one adopted by History, history.mit.edu/about/statement-diversity. Consistently communicate respect for others, even when it is difficult to do so. Praise others.

Assistance: Bring in MIT resources to help when needed – you can’t do it all. Become familiar with, and recommend as needed, MyLife Services (a network of experts to help with life concerns), the ODGE/GSC Best Practices in Advising guide, the Chancellor’s resources – Student Resources Summary) and the MIT faculty concierge portal.

Assessment: Request from Institutional Research data similar to what is assembled on the next two pages. Share it with your Visiting Committee.

These recommendations are only a few of the things I did or would do now as a Department Head. One may choose to go beyond them, for example, by creating a Diversity and Inclusion Strategic Plan, by training and assessing mentors, by organizing community events, etc. Much more has been elsewhere about outreach and mentoring efforts. In Physics, it was helpful for all junior faculty to take MIT’s two-day workshop in Leadership Skills for Science and Engineering Faculty. Once the basics of empathy, community, and culture are in place, MIT faculty will come up with endless good ideas to advance respect and caring.

Do these efforts work? Do they add value? The set of physics departments nationwide provides evidence that they do.

First, our US News and World Report ranking improved: in 2014, MIT Physics took sole possession of the #1 position, with a 5/5 reputational ranking. No other department in the country has this distinction, in any area of Engineering, Health, Science, or Social Science. (MIT Chemistry, Computer Science, Economics, and Mathematics are tied with others for #1 with 5/5 rankings.) Conversations with colleagues across the discipline suggest that our reputation improved because of our efforts to advance a respectful and caring community.

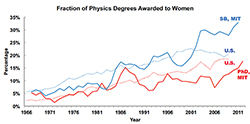

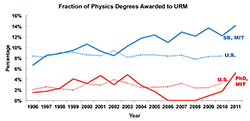

Second, the ability to recruit, retain, and graduate or promote talent can readily be measured. Indeed, the Provost annually reports to the faculty on these matters, as called for by a 2004 faculty resolution. However, MIT-wide data do not help departments to assess themselves. Each department can and should assemble data similar to what is shown in the two figures below:

When I became Department Head, I learned that we were doing poorly graduating Black and Hispanic PhD students. We had declined following a long history of success; deceased astronaut Ronald McNair, RPI President Shirley Ann Jackson, and National Medal of Science winner S. James Gates are among the many black scientists who received their physics PhDs from MIT. The concerns raised by graduate women were urgent for minority women and men. Response to their concerns reversed the trends so that the Physics Department met the goals of the 2004 faculty resolution to triple the number of underrepresented minority graduate students in fewer than 10 years (see figure above).

Similar data for faculty show a longer timescale for change. When I began, Physics had the smallest percentage of women faculty of any department. Nine years later, the number and percentage of female physics faculty have doubled.

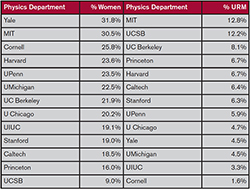

Efforts to improve the climate for one group help others. In the Physics Department, although the relative gains were most dramatic for graduate students, our undergraduate student diversity increased as well. The best way to interpret the numbers is to compare with peer departments. The following table shows Bachelors degree data for the top physics departments, averaged over a five-year period:

Such a comparison avoids the “pipeline” problem: all physics departments are recruiting from the same pool. The large variation across departments nationally is surprising and reinforces the perspective that academic departments have distinctive cultures that affect student outcomes. Is there a similar variation across MIT departments? I believe so, but until we have tabulations like these, we will not be sure.

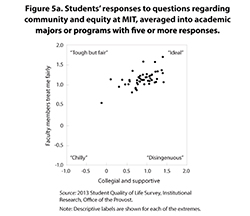

(click on image to enlarge)

to Questions Regarding Community

and Equity at MIT

(click on image to enlarge)

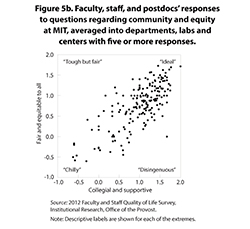

We do have some data concerning departmental climate at MIT. The figures above are from the ICEO Report. After poring over data from the 2012 and 2013 Quality of Life surveys, I constructed measures of collegiality (community) and fairness (equity) that correlated with what I had learned speaking with community members during 2013 and 2014, and which were significant in that the differences between departments were larger than could be accounted for by random sampling from a single population. In short, some departments have welcoming climates, many are tough but fair, while some are regarded by staff, postdocs, or faculty themselves as being rather chilly.

MIT staff, postdocs, and faculty have recently completed a new Quality of Life survey. Next year our students will take a similarly detailed survey. Efforts have been underway in many work units, including academic departments, to improve the climate so that more people thrive. New data will provide feedback to these efforts.

What did I learn as a Department Head? I learned that being #1 in the rankings is not enough; that it is possible for a Department Head to advance a respectful and caring community; and that doing so yields benefits for everyone. If we learned that caring is as important as knowledge, so will our competitors. Will MIT Department Heads be ahead of them?

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |