| Vol.

XXIX No.

4 March / April 2017 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

The Long- and Short-Term Budget Challenges

for R&D Support

The federal budget for research and development (R&D) faces major budget challenges ahead, both long and short term, which could have a profound effect on university research. The long-term challenge stems from the increased spending required because of the nation’s aging demographics, particularly the cost of health care. In the short term, there is a major battle shaping up over the federal fiscal year 2018 budget because of the Trump administration’s plans to cut taxes, raise defense spending, and fund new infrastructure, which would be offset by cuts in domestic discretionary spending, where most R&D is located. Finally, it is becoming increasingly clear that the country has been experiencing social and economic disruptions to its working class, which has thrown a wildcard into the ability of the political process to manage these developments.

The Long-Term Challenge

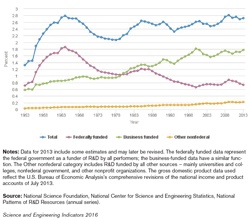

As noted, federal spending on R&D faces a growing challenge due to the growth of federal entitlement spending, principally for health care. Let’s first look at where R&D spending stands over time as a percentage of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Why compare R&D to GDP? Because this percent tells us about the size and strength of the nation’s commitment to R&D over time; internationally, this is a widely used benchmark to compare R&D investment levels, which, of course, are related to a nation’s innovation capability and corresponding innovation-based economic growth. As the figure below (from NSF 2016 S&E Indicators) shows, when federal and private sector spending on R&D are combined, U.S. R&D has been holding relatively stable since the mid-1960s, now at 2.8% of GDP.

This percentage is no longer the highest level among competitor nations, but still strong. However, when we look at the components, we sense possible trouble ahead. While federal R&D reached 1.8% in the mid-’60s, it had fallen by 2013 to less than half that level, to 0.8%. It was offset by growth in private sector R&D, which correspondingly rose from around 0.8% in the ’60s to 1.8%. The problem is that we are comparing apples to oranges, and they are not interchangeable: the public sector predominantly funds research and the private sector predominantly funds development. Research and development are, of course, related: development tends to leverage off of research over an extended period; although there is a significant lag time, a reduction in research commitment will eventually catch up to affect development capability. The optimal curve from an economic growth perspective would be two parallel rising lines, so the growth in one can keep leveraging continuing growth in the other. The U.S. now has an “X” curve – the lines are not growing in parallel.

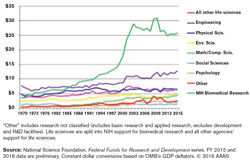

Not only is the research share of GDP funding on the decline, science funding across sectors is not uniform. The figure below (from AAAS) shows the sharp rise in total health research stemming from the doubling of research funding for the National Institutes of Health (NIH) between 1998 and 2003, although this level has been stagnant since then, offset slightly by a funding increase last year. Other scientific fields have experienced (using 2015 dollars) either a modest rise or stagnation between 1970 and 2016.

(click on image to enlarge)

But the pressure on science support is about to increase because deficits are about to grow again. The Congressional Budget Office’s 2016 Baseline estimates of federal deficits shows that although federal deficits rose sharply due to the Great Recession in 2008-09 to $1.4 trillion, they steadily fell back with the economic recovery to pre-recession levels by 2015. However, the CBO estimates show upcoming progressive deficit increases returning to the trillion-dollar level by 2024.

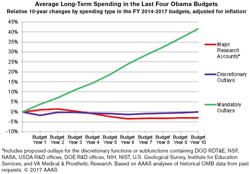

The figure below shows the AAAS’s estimates of the growth in entitlement spending during the Obama administration; this spending is “mandatory” because the government must meet its obligations to Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid recipients. This is the critical factor leading to federal deficits. In contrast, the government’s “discretionary spending” is in decline. This category includes the federal government’s non-entitlement spending for defense and non-defense government programs, from the Navy, to national parks, to NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology). This decline includes overall R&D spending at the major research agencies. The chart shows that entitlements (particularly health care) are absorbing all and more of the increases in federal expenditures, and this trend will accelerate as the demographics of an aging population expand.

(click on image to enlarge)

To summarize, the long-term prospect for federal domestic discretionary spending, home of all non-defense R&D, is not pretty; R&D will face growing pressure particularly from mandatory health care expenditures for decades to come.

| Back to top |

The Short-Term Budget Challenge

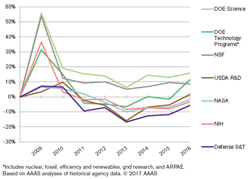

In 2012, as federal deficits still hovered about the trillion dollar level, the political parties agreed to a process to cut federal spending known as “sequestration.” While Democrats protected entitlement spending from cuts and Republicans prevented any tax increases, both agreed to focus deficit reduction on federal discretionary spending, a secondary priority for both. Following an initial budget cut of one trillion dollars, sequestration cut domestic and defense discretionary spending by another $1.2 trillion, imposed over a decade, from 2013-2023. Since federal R&D is discretionary spending, R&D was cut as well. Congress subsequently modified the cuts in budget agreements covering fiscal years 2014-2017, and R&D spending has recovered to approach 2012 spending levels. The figure below (from AAAS) shows, for major science agencies, first, the budget stimulus during the Great Recession where R&D was a significant beneficiary, and, second, the budget cuts imposed by sequestration starting in 2013. The figure shows the extent to which the agencies have recovered from sequestration.

But just as R&D spending was recovering from sequestration – which remains in place until 2023 – the new budget for fiscal year 2018 submitted by the Trump administration proposes to deliver a more draconian blow. The President made major campaign pledges to increase defense and infrastructure spending as well as to cut taxes. In its budget “blueprint” of March 16, 2017, the administration is seeking a $54 billion increase in Defense programs (and $2 billion in Homeland Security), which it proposes to offset with corresponding cuts to domestic discretionary programs. Some R&D highlights are identified below:

- NIH would be cut by $5.8b, or 18% to $25.9b and its institutes and centers are to have a “major reorganization.”

- The Department of Energy would be cut by 5.6% ($1.7b); within it, the Office of Science would be cut by $900m (17%) and ARPA-E (Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy) ($300m) would be eliminated; while not specified, the Budget indicated applied research at the Offices of EERE (Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy), Fossil Energy, Nuclear Energy, and Electricity would be cut by $2b.

- EPA would be cut by $2.6b (31%) and its Office of R&D would be cut by $233m or 93%.

- NASA would be cut by 0.8% to $19.1b, funds would be increased for Planetary Science (by 16% or $270m) and reduced for Earth Science (down $100m), with a new emphasis on manned missions. NASA’s education programs including Space Grant would be eliminated.

- The Commerce Department would be cut by 16% ($1.5b); within Commerce, NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) research and education would be cut by $250m (eliminating coastal and marine management), climate and climate observing programs cut by some 20%, and the Sea Grant program eliminated; NIST’s (National Institute of Standards and Technology) budget is not specified but its Manufacturing Extension Partnership would be eliminated.

- NSF was not mentioned in the document, although it was in a list of “other agencies” scheduled for an overall cut of 9.8%.

These cuts come in a context of a proposed 10.2% reduction across domestic agencies, including a 21% cut at Agriculture and a 28% cut at State. Because the cut in domestic discretionary programs (domestic spending is cut from $516b under current law to $462b) is balanced by a corresponding increase in defense spending (which increases from $549b to $603b) there is no effect on the growing budget deficit. There is an irony here: only some 16% of the total federal budget is now in the domestic discretionary category; this category is now such a modest part of the total budget that even massive cuts in this category have limited effect on the deficit.

Although Candidate Trump pledged to both balance the budget and pay off the national debt of $19 trillion in eight years, he has been unwilling to address mandatory spending, which (plus interest on the debt) is over 60% of federal spending.

The March document is only a preliminary budget – a full budget will be submitted in May. The new budget will still have to clear Congress. While most had been assuming that the administration could use the Budget Resolution and follow-on Reconciliation process to pass it outside of the Senate filibuster process, the deficit increase required by the proposed defense spending may trigger a 60-vote requirement in the Senate, which means that both parties will have to consent to the changes, likely triggering complex procedural maneuvers that will determine whether these cuts will go into place.

To summarize, there are long-term budget pressures primarily due to the aging demographics in the U.S. and the corresponding cost of health care programs. Budget deficits, after declining in the recovery from the Great Recession, are rising again. This puts ever-growing pressure on federal discretionary spending, source of R&D spending. Meanwhile, in the short term, just as science agencies have been recovering from the sequestration cuts imposed in 2012, the President’s FY2018 budget proposal makes major and unprecedented cuts in R&D programs. A major legislative battle late this spring will determine whether and to what extent these R&D cuts will go into place.

The Growing Challenge in Making the Case

Of course, R&D is not part of the problem; it is arguably part of the solution because of its potential to contribute to economic growth through technological innovation. Even a modest increase in growth helps offset the demographic effects of rising mandatory spending and the budget deficit. Although MIT’s Robert Solow led the development of innovation-based growth theory, so far neither political party has fully accepted this as core doctrine. In a way, the two political parties still seem locked into the two pillars of growth theory from classical economics that Solow’s work displaced: Republicans tend to embrace capital supply and Democrats labor supply theories. While both factors remain important, they are not the dominant causative growth factor Solow identified: technological and related innovation. Arguably, until this is better understood, R&D support will remain under long- and short-term budget pressures.

However, this foundational argument for R&D is getting harder to make. Economist David Autor and his colleagues tell us our society increasingly looks like a barbell, with a quite successful upper middle class on one bell, a thinned-out middle, and the other bell, a growing, lower pay, lower end services sector. This in a nation that has long prided itself on its social mobility and economic opportunity.

Instead, for example, median income for men without a high school diploma has declined by 20 points between 1990 and 2013, and those with a high school diploma or some college declined by 13 points.

We have a growing underclass that is increasingly our middle class. Labor economist Richard Freeman argues America’s growing income inequality is reaching developing world levels. Economic historian Peter Temin’s new book, The Vanishing Middle Class, documents just that. He shows, for example, the declining middle class share of national income from 60% to 40% between 1971 and 2014, and the stagnation of wages for manufacturing workers between1975 and 2014, despite significant productivity gains.

In this context of growing economic inequality, technological advance is not necessarily viewed as an unalloyed good; an increasing part of the working class sees it as a job threat. We face a growing problem of jobless innovation. Universities, with their rising costs, are too often viewed as elite bastions, not engines of mobility, despite arguments to the contrary. Challenges to our society are now at hand regarding quality job creation, manufacturing, the future of work, and education and training that can raise skills and economic opportunities. Can universities play a role in thinking through these problems? Can MIT? Arguably, universities need to be part of the solution, and seen to be part of the solution, to these problems. The university research model itself may have a stake in the outcome.

William B. Bonvillian served eleven years as director of MIT’s Washington Office until February, and is now a lecturer teaching a course in science and technology policy for STS and Political Science. These comments are drawn from a talk he gave to the MIT Faculty Meeting on February 15, 2017.

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |