Cities are in constant flux. What was once a proud monument to the strength of a local industry or a testament to local wealth is now a decrepit factory, or a mansion turned tenement. With a closer investigation, we can find artifacts and traces, helping us to uncover these relatively unknown histories and to understand a neighborhood’s sense of place. My site lies in Boston’s famed Fenway neighborhood, bounded by the Olmsted’s Fens on the West, by Brookline Ave on the North, and Queensbury Street to the South, and Kilmarnock Street to the East. Combining evidence from historical maps with the artifacts and traces left by the site’s transportation, new developments, and architecture led to identifying the trend towards gentrification across the site.

Figure 1. Dilapidated store fronts on Brookline Avenue. Personal photograph.

Figure 1. Dilapidated store fronts on Brookline Avenue. Personal photograph.

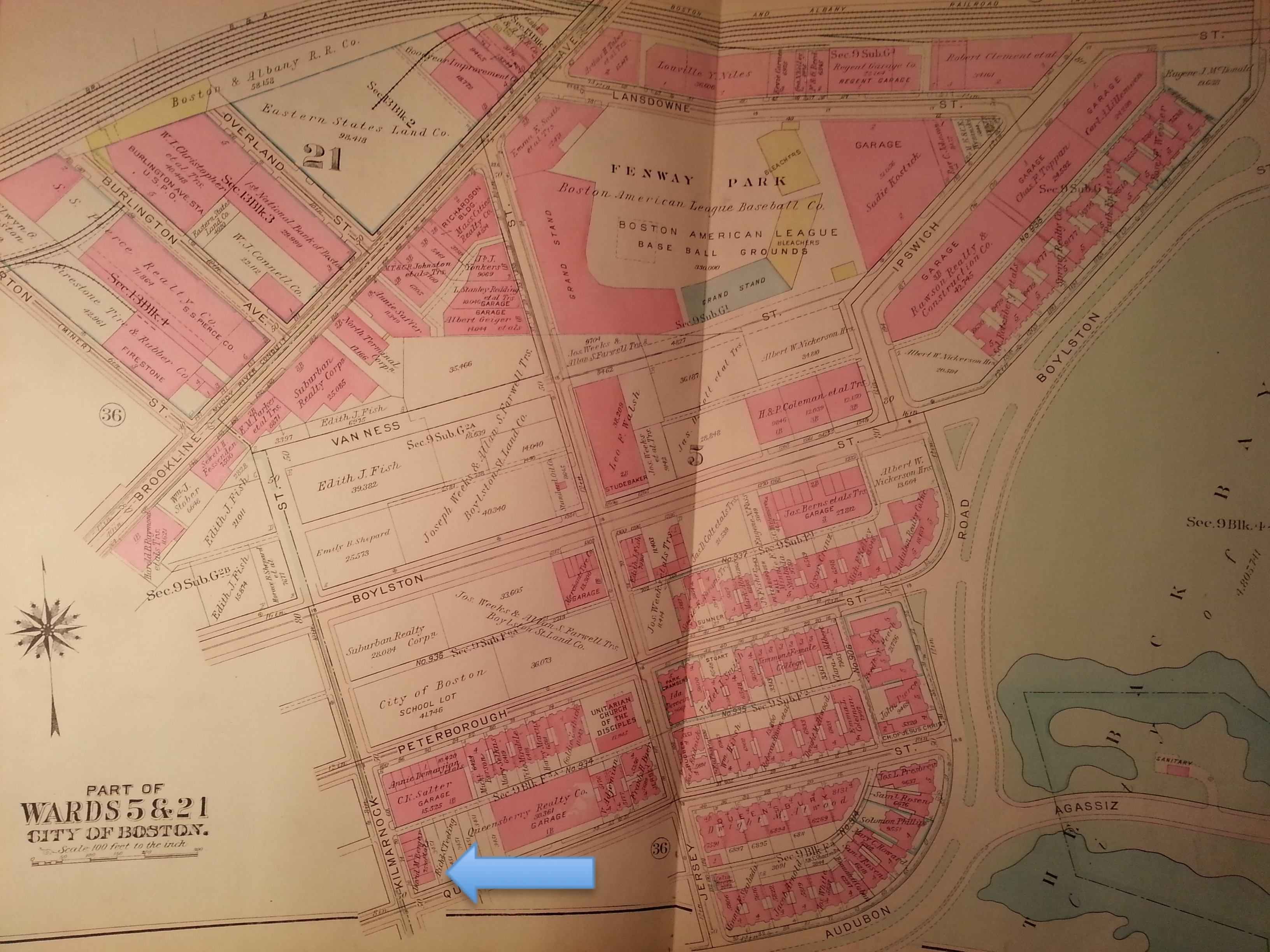

The dilapidated buildings in Figure 1 are traces of a long lost past. The brick storefronts were changes to the building, as there was a shift towards entertainment and retail on Brookline Ave. It is probable that these brick storefronts were originally garage bays for automobile service businesses, as was shown in the 1908-1938 Sanborn Maps in Figure 2. As the urbanization of the neighborhood led to an influx of young people less dependent on automobiles, and as land values increases priced these relatively undesirable businesses out of the area, these modifications were done to accommodate retail lessees. Nearby stores are primarily leisure-focused venues; bars, restaurants, and arts and crafts retailers prevail. Traces of the old auto shop businesses still remain, but in a modern flavor. Figure 3 depicts a European vehicle service shop. As the neighborhood increasingly caters to an affluent demographic, this mechanic survived by servicing luxury European car makes. It is a reminder that economic forces are very frequently the proponents of change of any neighborhood.

Figure 2. Brookline Avenue is dominated by automobile garages, service shops, and related businesses. Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1908-1938, via Massachusetts Institute of Technology Roach Library.

Figure 2. Brookline Avenue is dominated by automobile garages, service shops, and related businesses. Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1908-1938, via Massachusetts Institute of Technology Roach Library.

Figure 3. Sign advertising a European automobile mechanic shop. Harkens back to when the site was populated by many auto service businesses. Personal Photograph.

Figure 3. Sign advertising a European automobile mechanic shop. Harkens back to when the site was populated by many auto service businesses. Personal Photograph.

Away from the ‘hot’ real estate of Brookline Avenue, artifacts of the neighborhood’s involvement with the automobile industry are still present. There is a still functional taxicab service station and garage Figure 4 that has retained its original building, despite it being relatively outdated. In a modern twist, all of the taxicabs I saw in the facility were clean-hybrid vehicles, far separated from the noisy, high maintenance, and heavily polluting vehicles of half a century past. The building is an artifact of the past, the vehicles, an artifact of contemporary technology.

Figure 4. Taxicab service station and garage on the site. Likely virgin construction from the earliest development of the site. Personal photograph.

Figure 4. Taxicab service station and garage on the site. Likely virgin construction from the earliest development of the site. Personal photograph.

Interest in bicycling among urban residents is also resurgent. While surveying the site, I saw new bicycle stands installed on several sidewalks, as seen in Figure 5. The growth of bicycling has also prompted the Hubway shared bicycle system, which has a station at the intersection of Brookline Avenue and Boylston Avenue. [1] The system appeals primarily to the young urban professional or the well-to-do, as well as the college students who often receive subsidized plans through their universities. [2] Landlords have also accommodated this growing trend; I noticed a locked bicycle room in the alleyway of a residential building, in Figure 5. The growth of both personal and shared bicycle infrastructure is part of a national trend among major American metropolises – cities like New York, Chicago, and San Francisco have implemented bicycle sharing systems as well as bicycle lanes. It is also an artifact indicative of the past; because the area was planned and built before the advent of the post-World War II suburban pattern, the neighborhood was dense enough to make bicycling a viable option. These planning decision had such an impact on the development of the site that more than a century after the neighborhood’s creation, this new transit option has been successful.

Figure 5. Top, showing the bicycle room in an apartment complex. Bottom, showing public bike racks installed. Personal photographs.

Figure 5. Top, showing the bicycle room in an apartment complex. Bottom, showing public bike racks installed. Personal photographs.

Figure 6. The Fenway Triangle Trilogy development in the background, in contrast to the older, renovated building in the foreground. These are the two layers of the photograph. Personal photograph.

Figure 6. The Fenway Triangle Trilogy development in the background, in contrast to the older, renovated building in the foreground. These are the two layers of the photograph. Personal photograph.

In Figure 6 the foreground shows a relatively recently renovated building, being used by retailers and office space tenants. In the background, the high rise Fenway Triangle Trilogy development is visible. The photo has two layers, representing two different eras of buildings, as well as two approaches to redevelopment. The older building is a trace back to the original retail and automotive uses of Brookline Avenue’s property; the newer one in contrast shows a developer’s vision for the future of the neighborhood. Excitingly, this new post-2000 layer continues to grow: just across the street from this development, Figure 7 shows a new building by the same developer under construction. This development is also a mixed use building – the banner depicts office, residential, and retail availabilities.

Figure 7. On the right side, a new development along the extended Kilmarnock Street, which now intersects with Brookline Ave. Personal photograph.

Figure 7. On the right side, a new development along the extended Kilmarnock Street, which now intersects with Brookline Ave. Personal photograph.

That the two adjacent developments are mixed use is not an anomaly – a lot of new construction is architected with this in mind. It is a trend not unique to Boston – it is happening nation-wide, as developers seek to hedge their risks, avoiding tying their investments to one particular sub-market. It is evidenced by large developments like Wolf Point in Chicago [3] and Hudson Yards in New York City. [4] It also signals a return to the planning ideals of the pedestrian friendly city, with each neighborhood being largely self-contained – as Kenneth Jackson described was the original form of the city in Europe and America. [5] The mixed use trend is also part of a larger shift in city planning towards ‘new urbanism,’ a style of city planning that incorporates a lot of changes in the city.

The development and its nearby neighbors are artifacts of Boston’s booming economy and return to international prominence. After decades of disinvestment, a stagnant economy, and poorly executed urban renewal projects, Boston’s unrivaled collection of educational institutions have led the city’s economic revival in the high value areas of technology, medicine, and finance. As an artifact of the current times, it also shows the renewed interest in urban living, primarily by the young educated population.

Figure 8 depicts a building with an attached parking garage. The Brookline Avenue facing auto-entrance was bricked closed, and the driveway was converted to a park-like space. The end of the driveway was covered in the existing landscaping, as evidenced by the young trees in the foreground compared to the large, old trees on the sides of the driveway. The modification was constructed likely to improve traffic flow and decrease cars travelling across the sidewalks onto the driveway. This is reflective of the national trend for traffic management along major pedestrian thoroughfares. The Fenway Triangle Trilogy project also raised concerns among the community about the impact on traffic flow that were ultimately addressed. [6] Hayden explains that public meetings “offer opportunities for discussion of places. Everyone on a project team – historians, artists, administrators – needs contact in open public meetings. It is also important to know how neighborhoods have reacted to history projects, landmark projects, or public art projects in the past: which ones succeeded, which ones failed, and why.” [7] It was likely through the directives of the local government combined with the input of the community that the current, highly functional state was reached.

Figure 8. Parking garage attached to building with an entrance bricked closed and a repurposed driveway. Personal photograph.

Figure 8. Parking garage attached to building with an entrance bricked closed and a repurposed driveway. Personal photograph.

Figure 9. Original construction apartment building. Note how the crown molding roof decoration does not extend all the way around the building. Personal photograph.

Figure 9. Original construction apartment building. Note how the crown molding roof decoration does not extend all the way around the building. Personal photograph.

Figure 9 is an artifact of the original neighborhood. It is a building originally constructed in the early 20th century, as evidenced by the Sanborn Map in Figure 10. The most interesting element of the building is the “crown molding” decoration. It only extends around the parts of the building that are visible from Kilmarnock Street. This is because the undecorated part faces the alleyway. Even decades ago, cost cutting measures were prevalent. This was done under the assumption that the undecorated portion would be hidden from view behind another building on the block. The expected developments never materialized; instead that adjacent lot was filled by a suburban-style supermarket. Even though the parcels in this neighborhood were among the last developable land in the city of Boston, the onset of the Great Depression led to a lack of capital investments. By the time Boston ended its decades of economic malaise as its economy diversified away from manufacturing and transportation, white flight and the national trend towards suburbanization had taken root. The unusual mark it leaves behind Figure 11, because of its visible location from Boylston Avenue, is a trace to a past that is quickly disappearing as cranes pierce the sky, changing the neighborhood forever.

Figure 10. Highlighting the building in Figure 9. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1937, via Massachusetts Institute of Technology Roach Library.

Figure 10. Highlighting the building in Figure 9. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1937, via Massachusetts Institute of Technology Roach Library.

Figure 11. The building in Figure 9 visible from Boylston Avenue, including the visibly missing crown molding. Personal photograph.

Figure 11. The building in Figure 9 visible from Boylston Avenue, including the visibly missing crown molding. Personal photograph.

As the neighborhood continues to increase in affluence because of the improved housing stock and increasing cost of living of Boston, the commercial spaces are also redeveloping. Figure 12 shows two layers of development. In the foreground, a relatively upscale bar and club called Church opened in the past decade. The outdoor seating was a sign that it was a relatively new development; none of the other commercial buildings on the site had enough of an offset to create sufficient space. It was also not present on the 1992 Sanborn map in Figure 13. In the background layer, an old convenience store and corner pizza shop continue to operate, in a building present on the 1928 Bromley map, Figure 14. This trend of new businesses and redeveloped homes catering to the young bourgeoisie exemplifies the national trend of gentrification.

Figure 12. A two layered photograph, showing old and new restaurant. Personal photograph.

Figure 12. A two layered photograph, showing old and new restaurant. Personal photograph.

Figure 13. The new retail establishment called Church is not present. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1992.

Figure 13. The new retail establishment called Church is not present. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1992.

Figure 14. The building in the background in Figure 12 is highlighted on this map. Bromley 1928, via Massachusetts Institute of Technology Roach Library.

Figure 14. The building in the background in Figure 12 is highlighted on this map. Bromley 1928, via Massachusetts Institute of Technology Roach Library.

Behind the site’s largest continuous development of residences, a large parking lot stretches wall to wall, filling this dead space, as visible in Figure 15. It serves not only to hold residences’ vehicles, but also for sanitation and repair work. The parking lot itself is the modern layer in this photo, surrounding the early 20th century homes. Within the parking lot, several empty reserved ZipCar® spaces in Figure 16 are an artifact of the growing ‘sharing economy.’ Although small in scale, it again reflects the landlord’s desire to appeal to young professionals. Hayden describes how “something as basic as a railroad or streetcar system changes the quality of everyday life in the urban landscape, while marking the terrain. For some it provides jobs in design, or construction, or operation, or maintenance; for others, it makes a journey to work through the city possible; for a few, it may bring profits as an investment.” [8]

Figure 15. Backside of apartment complex. Personal photograph.

Figure 15. Backside of apartment complex. Personal photograph.

Figure 16. ZipCar reserved spots visible in parking lot of apartments. Personal photograph.

Figure 16. ZipCar reserved spots visible in parking lot of apartments. Personal photograph.

Even some of the new construction takes stylistic cues from the neighborhood’s existing designs. Figure 17 is an image with two layers of development. On the right, it contains the older layer, an original apartment constructed at the turn of the twentieth century. On the left, a new building takes some basic elements from the original designs. It borrows the bay window concept, but makes the implementation shallow. It includes a “crown molding” on the roof, but an extra floor is added above. It is built in a larger, more continuous and uniform manner than its historical counterpart. The practice of borrowing certain elements to fit in with what is perceived to be the correct architectural style is widespread; in the suburbs, upper middle class ‘McMansions’ are often decorated with faux neoclassical elements. They are designed from the inside out, leaving a bloated or disproportioned outward appearance. [9] So the building on the left is actually an example of a national trend of low architectural quality mass produced mid-to-upper market homes. Luckily, the city of Boston has become stricter in its approval of new developments, taking a closer look at architectural quality and taking input from the community before approval.

Figure 17. Two layered photograph, with a new development on the left side, and an original development on the right side. The new development has drawn some stylistic elements from the original buildings. Personal photograph.

Figure 17. Two layered photograph, with a new development on the left side, and an original development on the right side. The new development has drawn some stylistic elements from the original buildings. Personal photograph.

Today, South Fenway is in its greatest period of flux since its inception. It is undergoing a process of gentrification that has lasted for more than a decade, since the inception of Ramler Park. Nationally, neighborhoods are gentrifying for the same reasons that motivate gentrification on the site – the increasing cost of living, a lack of new developments in traditionally attractive areas, and a ripe with development opportunities. It leads to a surge in investment in the area, and an influx of young, moneyed, and environmentally conscious residents, often termed “yuppies.” The trend has brought about tremendous positive impact on the neighborhood – the creation of Ramler Park, the redevelopment of underutilized parking lots into residences and shops, and a wave of new businesses to serve the new clientele. Elements of its culture were surely lost as the original residents slowly moved away, but this is the reason American cities are so dynamic.

Still, there remain traces and artifacts of the neighborhood’s humbler days, via its architectural legacy, preserved via Boston’s strict and byzantine building codes, and remaining original businesses. It is this integration of the new and the historically significant that make the character of this site unique, even among Boston’s incredibly diverse neighborhoods. It has preserved the architectural features and the stories of its past; it has turned inhuman parking into exciting public and private space, energizing the streets. It has done so without tremendous disruption to the community. South Fenway offers a strong model for successfully managed gentrification, for cities like San Francisco, New York, and London, which suffer from a lack of housing combined with a glut of wealth.

1. The Hubway Company Inc., “Station Map,” Accessed April 21 2014, https://www.thehubway.com/stations

2. Rose, Joel, “Shifting Gears To Make Bike-Sharing More Accessible,” National Public Radio, December 12 2013, http://www.npr.org/blogs/codeswitch/2013/12/12/243215574/shifting-gears-to-make-bike-sharing-more-accessible

3. Wolf Point Owners, LLC., “Wolf Point Development Proposal,” Accessed April 21 2014, http://www.wolfpointchicago.com/.

4. Related Co. Development, “Hudson Yards,” Accessed April 21 2014, http://www.hudsonyardsnewyork.com/.

5. Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 58.

6. Brown, Sara, “Fenway Development would add new street,” Boston.com, February 24 2011, http://www.boston.com/yourtown/news/fenway-kenmore/2011/02/fenway_reacts_to_proposed_mixe.html

7. Dolores Hayden, The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1997), 229.

8. Ibid 22.

9. Fletcher, June. “McMansions Out of Favor, for Now,” The Wall Street Journal, June 29 2009, http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB124630276617469437?mg=reno64-wsj&url=http%3A%2F%2Fonline.wsj.com%2Farticle%2FSB124630276617469437.html

Brown, Sara. “Fenway Development would add new street.” Boston.com. February 24 2011. http://www.boston.com/yourtown/news/fenway-kenmore/2011/02/fenway_reacts_to_proposed_mixe.html

Fletcher, June. “McMansions Out of Favor, for Now.” The Wall Street Journal. June 29 2009. http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB124630276617469437?mg=reno64-wsj&url=http%3A%2F%2Fonline.wsj.com%2Farticle%2FSB124630276617469437.html

G.W. Bromley & Co. Boston MA. Boston: G.W. Bromley & Co. 1928.

Hayden, Dolores. The Power of Place: Urban landscapes as Public History. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1997.

Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Related Co. Development. Hudson Yards. Accessed April 21 2014, http://www.hudsonyardsnewyork.com/

Rose, Joel. “Shifting Gears To Make Bike-Sharing More Accessible.” National Public Radio. December 12 2013. http://www.npr.org/blogs/codeswitch/2013/12/12/243215574/shifting-gears-to-make-bike-sharing-more-accessible

Sanborn Map Company Inc. Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps Boston MA. Pelham: Sanborn Map Company. 1908-1939. Via MIT Rotch library website. Accessed April 20 2014. http://sanborn.umi.com.libproxy.mit.edu/ma/3693/dateid-000019.htm?CCSI=254n

Sanborn Map Company Inc. Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps Boston MA. Pelham: Sanborn Map Company. 1992.

The Hubway Company Inc. Station Map. Accessed April 21 2014, https://www.thehubway.com/stations

Wolf Point Owners, LLC. Wolf Point Development Proposal. Accessed April 21 2014, http://www.wolfpointchicago.com/