Fall 2000

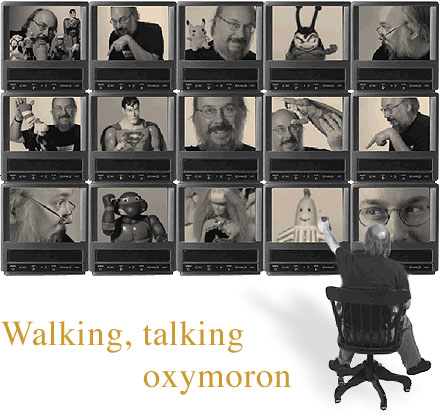

Walking, talking, oxymoron

Henry Jenkins analyzes and decodes the meaning behind pop cultural icons and the digital technology universe.

Seven notables contemplate the state of humanities, arts, and social sciences at MIT and beyond.

![]()

SHASS 50th anniversary celebration

October

6-7th

more

info

To celebrate its 50th Anniversary, the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences will hold a Colloquium on October 6 and 7, 2000. A distinguished group of faculty and scholars from MIT and other institutions will meet to discuss some of the fundamental questions that have occupied the attention of the School from its inception and that continue to animate the School's intellectual life.

![]()

Soundings

is a publication of the School

of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

at MIT

Editor:

Orna

Feldman

Editorial Assistance:

Sue

Mannett

Elisabeth Stark

Layout and Art Direction:

Conquest

Design

Online

Publishing:

August Design

Design:

MIT

Publishing Services Bureau

"We are in the midst of a media revolution of extraordinary scope and impact. We've only seen its equivalent a handful of times in the history of the world."

Pop culture and media analyst Henry Jenkins explores

high-tech folkways, our mediated culture, and other questions central

to democracy.

Photo:

Graham

G. Ramsay

In the wake of the Columbine shootings, the media has stepped up charges that video games and other media socialize children to violence. You argue that this view is misguided.

Politicians and the "media effects" researchers promote a very simplistic stimulus/response model of what media does—a kind of monkey see, monkey do. Their first move has been to try to decredentialize the humanities in this discussion and to isolate the discussion of "violent images" from concerns about culture, community, content, context, and change. In the real world we don't encounter violent images, we encounter violent stories. Our culture tells a wide range of different stories about violence and we need to restore issues of meaning to this discussion. We should be talking about the emotional investments we make in these media narratives, how we understand media content in relation to the world around us, and how media representations affect our sense of ourselves.

Are you concerned that violent fantasies can desensitize people to real-world violence?

For starters, most kids make a clear distinction between the space of fantasy and the space of reality. Fantasy is a cultural space people enter to do things they would not want to do in the real world. It's a space of authorized transgression, where you explore feelings, get rid of pent up anger, work through frustrations. You imagine yourself doing things that would literally be unimaginable in your everyday life. We want, to some degree, to be desensitized to what we're doing in fantasy so we can experience the pleasurable release that fantasy embodies.

What is the big draw in these games?

A variety of things: One is empowerment. The need to feel powerful, to have autonomy, is a really important thing for kids who are picked on all day at school, who are told by parents and teachers what to do all the time. I would like for the game industry to find a broader vocabulary for representing power—persuasive power and power of movement. There are lots of ways of envisioning power that don't involve pummeling or dominating someone. The single most successful category of games in the computer industry, in fact, is sports games. First-person shooters, by and large, have not been financially successful. So, in fact, the center of the market is not where the public perceives it to be.

Are you saying the public response to violent media images is totally misguided?

Most of the anxiety arises because of adult ignorance of new forms of popular culture that are not part of their own experience. Right now, public opinion is being shaped by people who read these images in the most literal possible way, who have no sense of humor and limited imaginations. Images that are intended to be hyperbolic, comic, ironic, satiric, and over the top are read literally. So we hear about these games where you drive your car down the street and you run over pedestrians—as if they were advocating such behavior rather than offering a tongue-in-cheek embodiment of our antisocial impulses.

Only politicians are reading them literally?

When you go to Washington you see Senators reading from index cards handed to them by their staffers about movies they haven't seen, television shows they haven't watched, songs they've never heard and video games they've never played. That's the root of the problem—the people making policy don't actually engage with the popular culture they're trying to shape. But the other problem is the way we deal with research about violence in this country, which is totally different from any other country in the world. We have funded a very narrow research agenda, the so-called media effects paradigm, which represents a small subset of communication research in the quantitative social sciences. Our leaders have embraced a very narrow set of methodologies and a narrow set of conclusions, rather than bringing to the table a broad range of perspectives, qualitative as well as quantitative, which might shed light on these questions.

What should the dialogue be focusing on?

We're in the midst of a media revolution of extraordinary scope and impact. We've only seen its equivalent a handful of times in the history of the world. One was the print revolution around Gutenberg, another the rise of modern mass media. The digital revolution is probably the third such revolution and it is impacting every aspect of our society. Every institution is having to respond to digital change, every value is under question—everything from how we do our banking to how we educate our children, choose political candidates and get the news.

Not all those are values; some are methods.

But these practices embody values. If you take politics: What is the relationship of citizens to their leaders? The premise of democracy resides on the concept of the informed citizen. How we get information, then, has an enormous impact on the quality of democracy. To talk about democracy without talking about the technologies of information and communication is to be totally abstracted from the real world. So in the midst of all of this profound change, why do our conversations always get trivialized? In the scope and scale of this change, whether or not a violent video game made a handful of kids shoot their classmates is simply not the biggest issue. It's a distraction. We need to be having a national conversation about the kind of society we are creating using these new technological resources.

Which issues are most important, in your view?

The digital revolution is a kind of cultural revolution. The new technologies are changing the way we relate to the storytelling systems of our society and are paving the way for an explosion of grassroots creativity by everyday people. Over the last 20 years we've had a variety of new technologies introduced into our lives which enable us to archive, annotate, remake and re-circulate media content. These technologies range from the photocopier, which became the poor man's printing press, to the VCR, which enabled us to alter the flow of images and literally remake the media images that come into our lives, through to the computer, the Web, digital photography, which allow us to remake and recirculate sounds and images. Digital technology gives us much greater control over the media, ideas, images and stories within our culture.

In broad brush strokes, what is the potential of this revolution?

Let's pull back a minute. For most of human history we've had a fundamental right to participate in the circulation and production of our culture's core stories. Every citizen was a storyteller. There might be bards who were specialists, but the culturally-central stories would be retold and recirculated. The rise of modern mass media resulted in a specialized class of commercial storytellers and tight controls over intellectual property. Stories became not only private property but corporate property.

Are you talking about Walt Disney?

Disney is a classic example. Disney raided the world's great folk and fairy tales, privatized them and sold them to us with very tight restrictions on how we can use them. If you're running an elementary school and you put a picture of Disney's Snow White on the wall, you may have a Disney lawyer knocking at your door. As we move to the digital world, that system of tight commercial control over our core stories is going to have to break down. The traditional gatekeepers won't be able to regulate the flow of ideas in such a decentralized cultural economy. These digital technologies are pushing us back toward a folk culture in which many more people will participate in the production and circulation of stories, though the media corporations won't let this happen without a fight.

The new technology is also creating a glut that can cause people to say 'Enough. I might find a little gem in this mass of information, but it's not worth my time.'

We're in a moment where there's an explosion of information, which is both liberating and overwhelming. Is this new world going to be the Library of Alexandria or the Tower of Babel? The Library of Alexandria represents a vast storehouse of human thought and accomplishment. The Tower of Babel represents the collapse of communication, as we cannot process and understand all of that information. Information is not knowledge. As humanists at MIT, we should be neither Luddites smashing the machines, nor technological utopianists imagining that the technology is going to lead us inevitably to the best of all possible worlds. Our job is to explain the choices we're facing and try to come up with a right course between them.

This grassroots creativity has led to an explosion of fragmented, niche cultures on the Web. What is the impact of this on our core consensus of values?

That's got to be a central concern for the humanities in the 21st century—how we develop some shared framework of value in such a world. There are some signs that popular culture is still based on a consensus model. Take television ratings. People are watching less television than they did a decade ago. On the other hand, individual broadcasts have set all-time ratings records, especially public rituals of mourning—like the funeral of Princess Diana. That's an interesting paradox, suggesting that despite narrowcasting, we still have some hunger for common culture.

Let's segue to Comparative Media Studies (CMS). What is its goal?

The ambitions of CMS are to train the future generation of storytellers, creative artists, policy makers, industry leaders, and journalists to look at core questions of media content, context and change. In the near future more and more of our stories will be told across media. The economic marketplace encourages that, technology encourages that, the way consumers relate to media encourages that. Part of a story may be told in a film, another on television, another in a comic book or on the Web. A storyteller is going to have to know about a lot of different media, their properties, their audiences and their potentials for telling stories. And to be a critic in the future means you have to look at intersections between these various media.

Does MIT bring some comparative advantage?

To be a humanist at MIT is to be a walking, talking oxymoron—a total contradiction. I see this as a strength, not a liability. There's an enormous opportunity because we're here where the various labs are developing cutting- edge technologies for tomorrow. We're ahead of the curve in understanding what those technologies are and how they will be used. And our backgrounds as humanists and social scientists enable us to ask important questions about how those technologies are going to impact society and culture.

Tell me about your involvement with teens; why are you putting your efforts here?

As I looked around, it was clear that high school students were among the first to really explore the creative and community-building potential of digital technology. They are really on the front lines of the digital revolution. The public reaction to Columbine revealed how much fear about digital technology there was in our culture. The week after the Littleton shooting, The Washington Post conducted a survey: 82 percent said the Internet was at least partially to blame for the shootings. Only 60 percent thought the availability of guns was to blame. More people were frightened about the Net than about guns. The culture warriors and counter-revolutionaries were taking aim at American youth. School boards and teachers were reacting in panic and cutting kids off from Net access. Washington policymakers were about to pass sweeping laws and regulations in response to their fear for children. There was a tremendous need for people with my expertise to step forward and articulate what was happening. We shouldn't be trying to silence American youth. We should engage them in a soul-searching conversation about the current state and future directions our culture is taking.

Does this involvement reflect the 'new humanism' you have spoken about?

Exactly. To start with, the new humanities is not about living in an ivory tower and pontificating about the past. I believe in applied humanism. We should be engaged in sites where change takes place—in government, in schools, in the community, in industry and in the popular press. Secondly, the new humanism doesn't speak jargon, but adopts a language that can be understood by the general population, because the questions the public is facing are too central to our democracy to be discussed behind closed doors. And third, the new humanists have to know this technology well and be capable of using it effectively to communicate ideas.

And how does the new humanist interact with social policymakers?

We've got to get out . . . to go to Washington hearings and write op-ed pieces. We have to become public intellectuals, because in a moment of cultural shift, humanists have an obligation to speak up for humanity, to talk about their culture, to ask questions about community, citizenship and creativity and do it in the places that will have an impact. If humanists can do that, then we're not going to be seen as ancillary. If we can articulate a response to social, cultural and technological change during a key moment of technological change, we are core to what MIT is about.

![]()

Copyright © 2000 Massachusetts

Institute of Technology