The Combat Zone Through Time

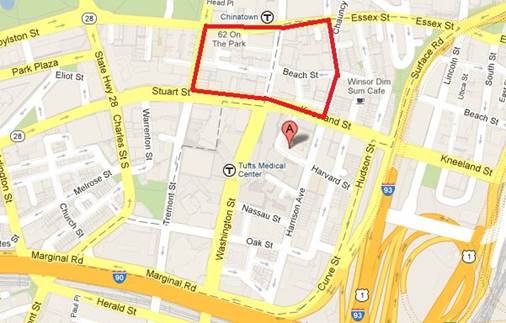

The Combat Zone and the adjacent blocks of Chinatown pack a lot of history and transformation into a small region. The area I investigated is bordered by Tremont St., Stuart St., Kneeland St., Harrison Ave., Essex St., and Boylston St., as depicted in the figure below. The most notable transformations in this site are the transitions from factories and colleges to theaters and parking lots. Other notable developments in the city are shaped by cultural factors of oppressed people, evidenced by Chinese laundries and a long standing Young Men’s Christian Union. Though there are several lenses through which to examine change throughout maps of my site, there are two that stand out as the most useful. (I have included maps at the end of the paper from 1867, 1895, 1929, 1951, 1962, 1974, 1981, 1992, and 2013 for reference). Transportation and the marginalization of the lower class were factors that can be traced throughout the development of my site.

“Boston, Massachusetts.” Map. Google Maps. Google, February 2009. Web. February 2013.

History of Chinatown

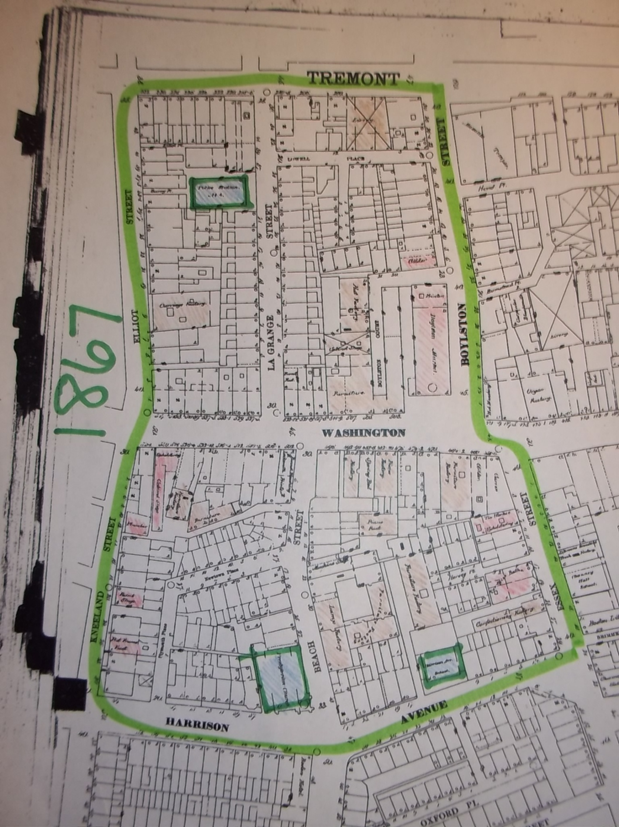

Even the history of Chinatown can be traced back to transportation and discrimination against the Chinese (Lee). Chinese were originally attracted to the United States because of the opportunities for work. One of the highest employing jobs was building the transcontinental railroad. Unfortunately, they were mistreated during and after their jobs. For instance, when the spike that united the railroad was driven in in 1869, the Chinese were not even featured in the picture. After they had completed work on the railroad, they tried to settle in areas on the West Coast. Ultimately they were driven from the west and had to move elsewhere. The first Chinese immigrants arrived in Boston in 1870 to break a strike. As evidenced by the 1867 Sanborn map of my site, there were a multitude of factories that these laborers could have worked in. These factories include confectionary factories, lamp Factories, and furniture factories. Such factories are widely distributed throughout my site.

Therefore, the development of the railroad inspired the Chinese to come to the United States, and their following discrimination against them pushed them to settle in Boston. They slowly started to develop and make a home for themselves. There is documentation that in 1875, there were 5 Chinese laundries on record. Some of these laundries can be seen in the 1895 map along Lagrange Street. By 1905, there were more than 100 laundries around Boston. These laundrymen would get groceries, mail, opium, and go gambling in central Chinatown. In the 1895 Sanborn map, there is a large grocery complex called Cobb, Bates, and Yerxa Grocers, where it is likely that these laundrymen bought their supplies. The fact that Chinatown needed to be accessed by Chinese in surrounding areas probably contributed to the development of the region as well.

The Chinese were able to make a home in this region presumably because living conditions near factories were not ideal. There are a number of small buildings nestled between factories and on small roads that were likely homes for lower income members of society, as seen in the 1867 map. Additionally, the first Chinese to Boston were single men who had come to America to find jobs. Since their families had not yet arrived due to numerous exclusion acts, they probably were not as concerned with finding the most ideal living conditions.

Further Chinatown Development

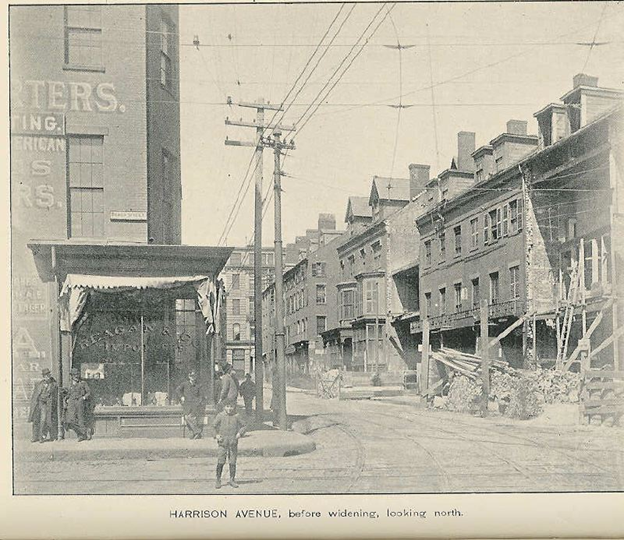

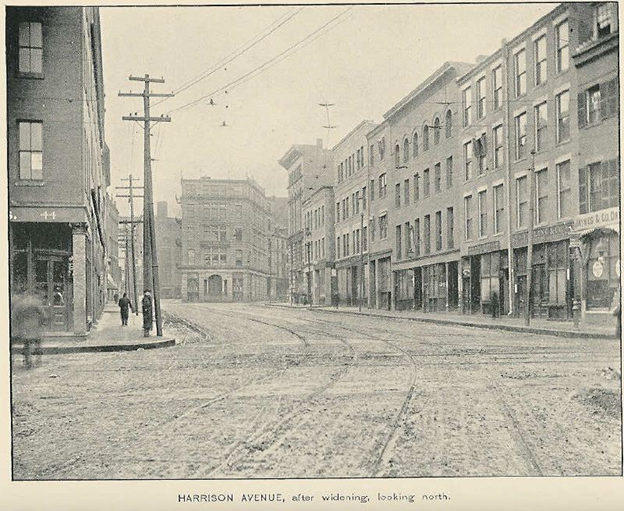

Ultimately, Bostonians were torn between hostility and support to the Chinese immigrants. They could indulge in opium but the level of gambling brought fear to the city. The fascination with the town can be demonstrated by Chinatown restaurants entertaining the future curator of the MFA in 1908 (Lee). However, in many cases, they were able to “push around” the immigrants in order to achieve city planning goals. Between 1867 and 1895, Harrison Avenue at the south edge of my site was widened so that it cut off numerous buildings and homes of Chinese residents. This is a clear example of taking advantage of lower income immigrants and ruining their homes to expand traffic routes. This is also another instance where transportation and marginalization tie together to shape the area. I included images of the street widening at the end of this paper.

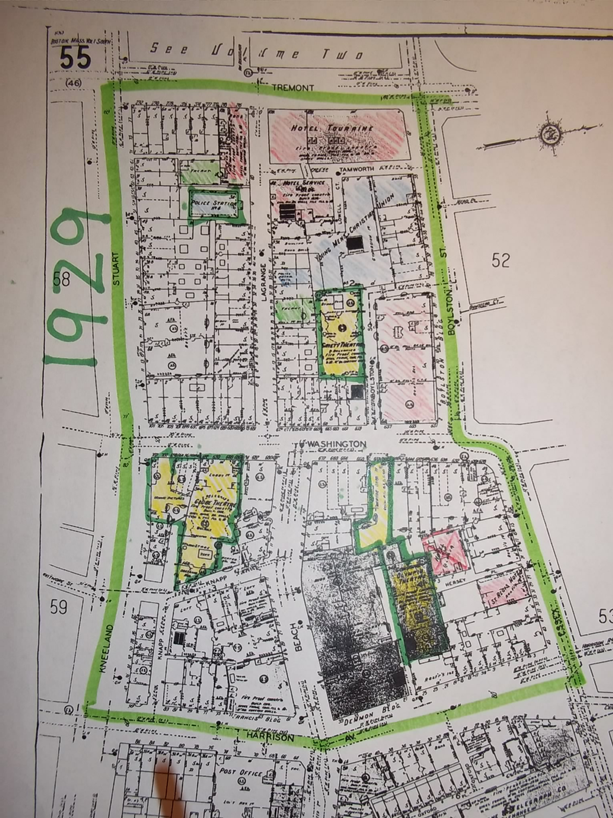

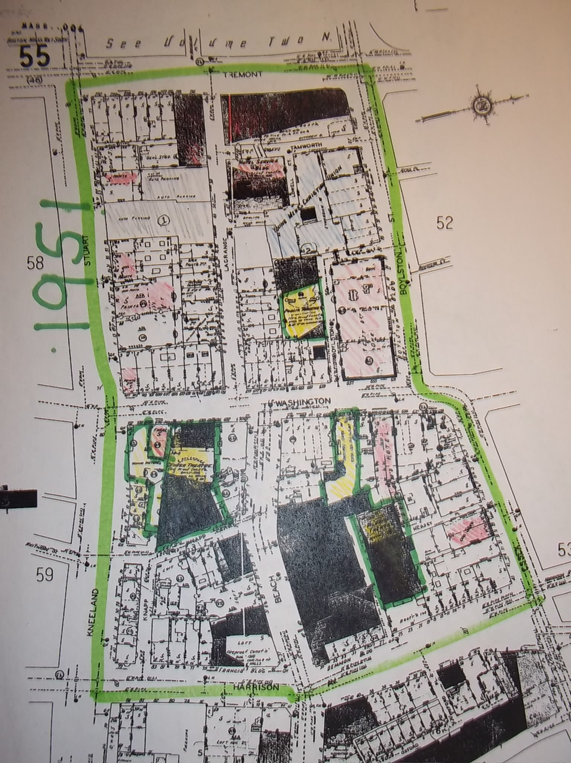

The Chinese prevailed and continued to increase their presence in the city. Family members could finally join the father in the laundries since restrictions were lifted from further immigration. In the 1920s the restaurants became the strongest point in China’s economy (Lee). Some restaurants can be found in the 1929 map. In the 1951 map, it is difficult to see much Chinese expansion into the site. This could be because in the 1930s several Chinese went back to China due to the Great depression (Lee).

Effect of a Religious Marginalized Group

Another marginalized group shaped the layout of this region as well. The Young Men’s Christian Union had developed by 1895. This organization has been remodeled, but is still present today; it is currently called the Boston Union Gym. This organization was founded by Unitarians who were not accepted into Boston’s Young Men’s Christian Association, which was an evangelical organization (Boston). The Young Men’s Christian Union covered a broad area so I believe the buildings could have been used for a variety of things including boarding, teaching, or recreation. The YMCU is perhaps the longest lasting organization of my site, proof that marginalized groups were an important shaping factor of the area.

How Transportation Shaped the City

Transportation was an important factor even before the Chinese arrived. The number of factories in the city could only have been possible if a railroad was nearby: “By the middle of the nineteenth century, steam engines with the ability to do the work of a hundred horses were coming into common use” (Jackson 35). The 1867 map indicates that Carriage Factories, lamp factories, and several others were present. By 1895 there were a few less factories, but they still played a major role in the area. According to Sam Warner, what ultimately contributed to this phenomenon were a “mix of new industrial methods and a pool of cheap labor that transformed Boston into the region’s largest manufacturing center” (Warner 8). Though manufacturing began with clothing, iron, and brass, it continued after the civil war with every type of manufacturing. This was because Irish immigrants were joined by Italians and other European Jews (Warner 8).

The effects of transportation can be seen most easily in these maps by the development of parking lots and parking garages. By 1929 there was a huge garage developed on Beach Street. By 1951 the garage still existed and a parking lot on Lagrange Street had been created. By 1962, there was an additional parking lot on the other side of Lagrange Street. Additionally, there was another one developed on the corner of Essex and Harrison. These changes were clearly a result of the increase of the number of cars on the road: “By 1925 Ford was turning out nine thousand cars per day, or one every ten seconds” (Jackson 161). By 1927, ownership of a car was no longer a luxury, but an essential part of middle-class living (Jackson 161). Another explanation for increasing parking lots could also have been a sign of devalued property. If the market was not right to make a building, a parking lot was a much cheaper, but useful alternative. Nonetheless, this the need for parking lots would not have existed without the appearance of cars.

A very specific example of how transportation affected the city was the removal of a police station. The police station on Lagrange Street was present in the 1867 maps up through the map in 1929. Previously, policemen had to patrol cities on foot. However, now they were able to patrol using cars so there did not have to be quite as many stations. The removal of a police station presumably wouldn’t have very much impact on a city. Though it is not clearly demonstrated on the map, less than 40 years after the removal of the station, Lagrange became an area of much crime and corruption in what would come to be known as the Combat Zone. Another example is the disappearance of the livery, which can be seen in the 1867 map. A family who owned a horse and carriage would have stored them in a public livery or a private structure on the rear of their property (Jackson 251). With the popularity of cars, a livery was no longer needed.

How Marginalization Allowed for Development

Immigrants and lower class citizens truly had an impact on this area. In The New England and Boston depression in 1921: “old Boston families left the city for the suburbs and when the new immigrants made a settled place for themselves in the city” (Warner 10) Therefore less privileged families were able to settle down in the city with the intent to stay permanently. It is important to note that slow change during the depression didn’t mean there was no change (Warner 10). For instance, there is evidence of a new St. Regis hotel by 1929 on Essex Street.

The city was also shaped with the intent to make it more modern. It is easy to make changes to a site where the majority of people are immigrants because they have no voice, and therefore many transformations occurred on my site. The period between 1790 and 1921 can be seen as a highlight of Boston’s history because there was a coalition of merchants, shop owners, and craftsman that “allowed the city to reach its civic peak” (Warner 6).There were several public undertakings in order to modernize the city. These included libraries, schools, hospitals, sewers and parks: “A series of institutions were established that enabled the city to become a leading innovator of modern world culture” (Warner 6). Some of these institutions are reflected on the site. For instance, there is a Presbyterian Church on Harrison Avenue as well as Harrison Avenue School (1867). Though each of these sites disappeared by 1895, there was a development of a business college. This college was located at the corner of Washington and Eliot and its offices were located at the corner of Beach and Washington.

One of the biggest changes in the city was the transition from factories to theaters. Mobility of Americans was increasing so it was possible to put all types of entertainment in a centralized location. The first theater, Lyceum theatre, showed up on my site by 1895. By 1929, presumably after Americans had access to more transportation, there were three theaters; the Gaiety theatre (previously the Lyceum theatre), the Globe theatre, and the Olympus theater. These theaters remained for several years.

There were also a plethora of hotels in this small region. Because this area was next to a train station it is likely that numerous travelers visited the area and needed a place to stay. The number of travelers could have been because of the strong railway system: “By the mid 1980’s. only a handful of cities – including New York, Boston, Chicago, and Philadelphia – could boast of impressive railroad commuter traffic” (Jackson 171). In 1895, there were at least three hotels on this site. Hotel Lagrange was situated on the corner of Lagrange Street and Tremont Street, Hotel Boylston was on the corner of Tremont Street and Boylston Street, and Brigham’s Hotel was on Washington Street. By 1929 hotel Boylston had become Hotel Tourrine. Hotel Tourrine was very large and even had a tunnel under Tamworth road to a “Hotel Service Building”. Also it appears Brigham’s hotel had been closed but was replaced with the St. Regis Hotel on Essex. Hotels remain a part of the site for a number of years, and even to this day there is a hostel located on Stuart Street.

The Combat Zone

The Combat Zone was a huge obstacle the Chinese and surrounding communities had to face. The Combat Zone was an area of crime and adult entertainment that was mainly concentrated on Washington Street and Lagrange Street (Lee). It was developed in the 1960s and lasted until the 1990s. It was an area filled with prostitution, gangs, and several strip clubs. The theaters became a business for sexual entertainment. This area formed because the City Hall had been redeveloped and the crime that was centralized there had to move to another place (Lee). Crime was able to manifest itself near Chinatown. Again, this is because I believe that because the Chinese were not given an equal voice in society and did not have any power to fight the changes.

Though it is difficult to see evidence of this dramatic new use of the area on maps, there are a few clues that suggest its presence. For instance, by 1962 a subway entrance had developed on Lagrange Street. According to Sanborn maps, it was probably removed in the 1980s. This development could have been a result of more effective transportation methods, but it also could have been shut down due to the danger of the area. Another small hint of the crime in the area was the development of the law firm Heathcote International on Stuart Street by 1992. Ultimately, the demise of the Combat Zone was brought about by stricter regulations but also by an increase in technology. Because home videos became available, men didn’t have to go to town to see the same thing (Lee).

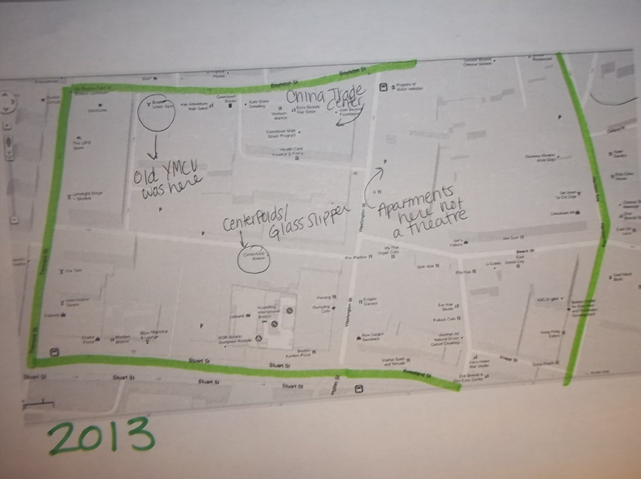

Since the demise of the Combat Zone, there has been a sense of urban renewal in the area. New apartment buildings have replaced the old theaters. Some traces of the Combat Zone still remain to this today however, including an adult store on Stuart Street and two strip clubs on Lagrange Street, Centerfolds and the Glass Slipper. However, most of this area is now characterized by new construction and Chinese restaurants.

Another recent development due to immigrant influence on the town is the China Trade Center located on Boylston Street. It was originally the Boylston market in 1867, and was the Boylston building in maps from approximately 1895 to 1981. The fact that it became the China Trade center shows that the Chinese community is finally gaining a strong voice in society.

Conclusion

From these observations it is easy to see how transportation and the marginalization of people were essential factors in the shaping of this region. More effective transportation was a key influence of manufacturing centers, clustering of hotels and theaters, the disappearance of the police station and livery, and the creation of a subway entrance in the area. The influence of lower class members of society can be seen be laundries, Chinese restaurants, the Young Men’s Christian Union, and the China Trade Center. Additionally, the discrimination against immigrants is reflected in my site by tearing down their homes to expand roads, by shaping the site to form a theater district, and by allowing an area such as the Combat Zone to be in Chinatown’s backyard. I believe that transportation and marginalization still play a role in this area today, though I believe the strongest influences now are the pushes for continuing modernization and renewal.

Works Cited

"Boston Young Men's Christian Union." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 04 Mar. 2013. Web. 05 Apr. 2013. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boston_Young_Men's_Christian_Union>.

Digital Sanborn Maps 1867 - 1970. N.p., 2001. Web. Mar. 2013. <http://sanborn.umi.com/cgi-bin/auth.cgi?command=AccessOK&CCSI=254n>.

"Harrison Avenue Widened." BostonHistory. The City Record and Boston News-Letter, n.d. Web. 05 Apr. 2013. <http://bostonhistory.typepad.com/notes_on_the_urban_condit/2006/03/harrison_avenue.html>.

Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier. New York: Oxford UP, 1985. Print.

Lee, Tunney. "Boston's Chinatown: Beyond Stereotypes, Food, & Boundaries." Boston Public Library, Boston. 13 Feb. 2013. Lecture.

Warner, Sam B. Mapping Boston. Cambridge: MIT, 2001. Print.

MAP KEY:

BLUE: Institutional

RED: Commerical

BROWN: Industrial

GREEN: Vacant Space

GRAY: Parking lots

YELLOW: Entertainment

Sanborn Map, Boston 1867. Web.

In the above map, there are a number of factories and stores, but there are also a number of institutions: a school, a church, and a police station.

Sanborn Map, Boston 1895. Web.

The above maps shows the development of a business college and theater, but still has a large number of factories. There is also now a Young Mens Christian Union on the Map. This map also displays the widening of Harrison Avenue.

Sanborn Map, Boston 1929. Web.

There are less factories and more theaters in the above map. There are a couple new vacant lots.

Sanborn Map, Boston 1951. Web.

The above map shows that the vacant lots have been filled in and there is now a parking lot where the police station was.

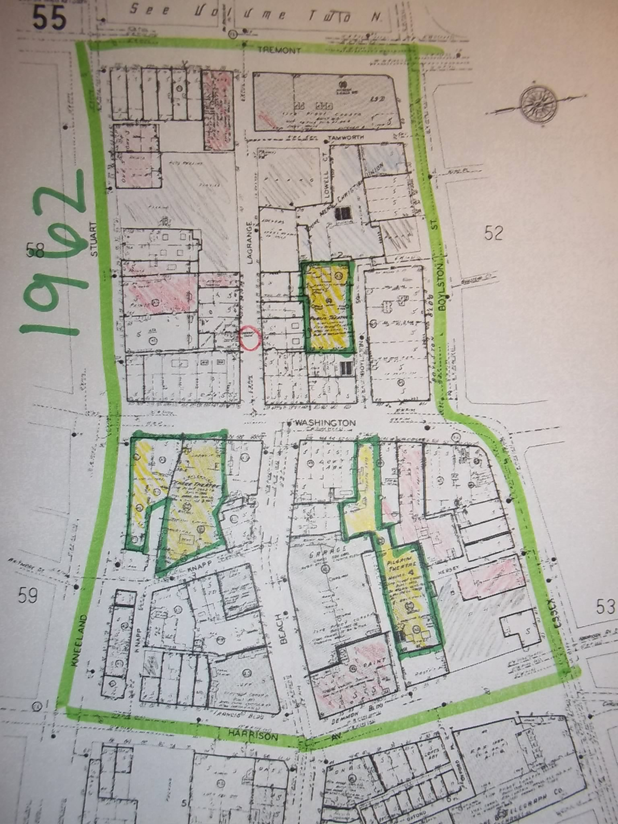

Sanborn Map, Boston. Vol. 1. 1962. Print. South.

The above maps shows the development of garages amd a subway entrance on Lagrange Street (circled in red).

Sanborn Map, Boston. Vol. 1. 1974. Print. South.

1962 - 1974 shows little change.

Sanborn Map, Boston. Vol. 1. 1981. Print. South.

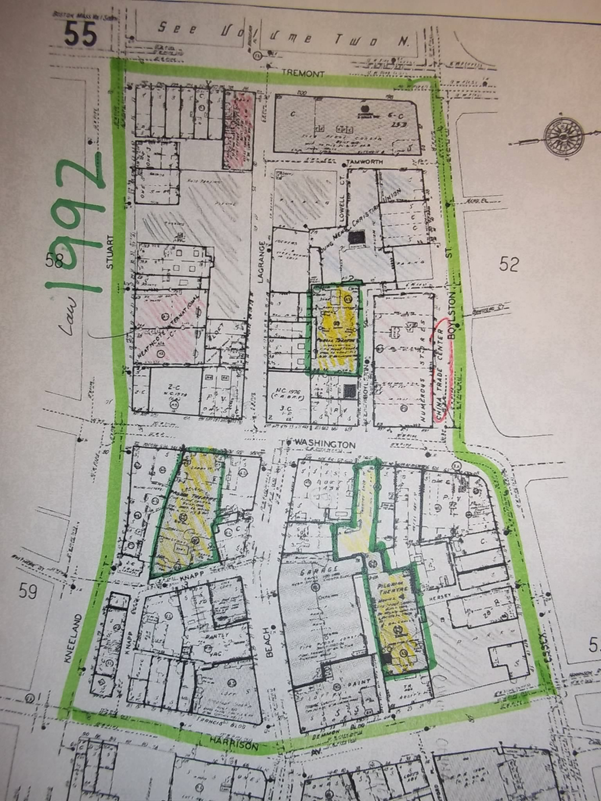

Sanborn Map, Boston. Vol. 1. 1992. Print. South.

Heathcote International and the China Trade Center have been created.

“Boston, Massachusetts.” Map. Google Maps. Google, February 2009. Web. February 2013.

“Harrison Avenue Widened” Before

“Harrison Avenue Widened” After