The Long Wharf and Faneuil Hall region of Boston has been driven and radically changed by the natural forces at play on the whole Boston area. The most prominent force that shaped Boston has always been the sea, and this is made even more evident in the Long Wharf area. The original Boston peninsula and harbor lead to the foundation of the city and the creation of the Long Wharf. As the city population rapidly increased due to the access to the sea, the importance of Boston grew and lead to the construction of the older buildings on the site, like the Old State House and Faneuil Hall. Yet the most dramatic change was the filling in of the land that compromises a majority of the site, creating a new coast line hundreds of feet from the old one, with new land filling in the space between. Man may have placed all of that fill, but it is still a part of nature. The soil subsides in places, and the land is used with a heavy focus on the harbor only a few yards away. It is this connection between the city and the environment, most importantly the Atlantic and Boston Harbor that has held sway and driven the development of the Long Wharf area into what it is today.

Walking around the site, it quickly becomes evident how much the sea holds sway on the area. Just looking at the buildings on the Wharf or just off of State Street, most of them are at least 100 years old, and have plenty of scars to show it. Be it cracking facades, sagging sidewalks, or even worn away stone, everything has been touched by the Atlantic. It can just be hard to see at times. While natural processes like hurricanes or storm surges flooding the city affect the city too often, the harbor acts on the city of Boston much more subtly.

The most prevalent method of acting on the Long Wharf and the Faneuil Hall region is through the landfill that almost the entire site sits upon. As Spirn tells us in the Granite Garden:

“Each year, shrinking or swelling soils inflict at least $2.3 billion in damages to houses, buildings, roads, and pipelines – more than twice the damage from floods, hurricanes, tornadoes, and earthquakes!... within the average American lifetime, 14 percent of out land will be ravaged by earthquakes, tornadoes, and floods – but over 20 percent will be affected by expansive soil movements.”

While that is the expansion of soil, the same effect can certainly be felt if the soil shrinks instead. That is exactly the most common process at work in the Long Wharf area. As one walks around the Faneuil Hall Marketplace, the signs become more and more evident to the naked eye. Take the window arches above the Coach and Ann Taylor retail spaces on the south side of the Quincy Market. Looking closely, it becomes clear that they are cracking vertically due to a sinking foundation. The lintel that forms the windowsill above these arches is also showing signs of the damage of soil subsidence. The granite block doesn’t match up with the window next to it, and clearly drops a few inches. This drop is exactly in line with the cracks on the arches below. At the bottom of it all is a visible drop in the pavement by the doorway of the shop, immediately below the previously listed damages. Other buildings nearby also have shown signs of wear and tear from years of sitting on landfill, with one even having metal bolts put into the stone façade in order to hold the building together.

This visible change in the soil that cause this crack is a direct result of the sea’s effect on the landfill that makes up the Long Wharf area. Much of the fill used to create new land in the area was just dumped in place and had buildings constructed immediately on top of it. Normally this happened before the fill had time to settle and properly compact together. This could even still be taking place as the sea gradually erodes at the fringes of the Long Wharf area, and so the land slowly begins to sink away and try and restore the Boston that was before settlers arrived. This is what causes, not just the damage to the Quincy Market already listed, but also to many other structures in the area. As the streets get closer and closer to the shoreline, they begin to sink into the ground. Walking down State Street gives the most obvious evidence of this, as every couple hundred feet the granite curbs drop a few inches, and this only ever happens facing towards the sea. Clearly the soil is subsiding at a more accelerated rate the closer it is located to the shore. This happens, not because of the difference in age of the landfill, as almost all of the Faneuil Hall and Long Wharf area was filled in at once, but it instead this subsidizing of landfill has been caused by the slow erosion of the waves on the shore, and of the water seeping into the ground. As Spirn tells us of landfill in Boston:

“The inevitable encroachment of land upon the water continues with the constant search for new space and a place to dispose of garbage. But the filled land is not without problems. Much of the land is quite low and susceptible to flooding. Extensive areas have a saturated soil whose fluctuating water level can damage building foundations”.

So the sea directly is able to damage these buildings by seeping into the soil and causing the landfill to fluctuate enough to damage foundations and, by extension, the structure of the building itself. This constant ebb and flow of the ocean has been at work in Boston since the city began, and it seems that there is nothing that can stop this juggernaut of nature from constantly being at play. The City just has to learn to adapt to it and build smarter.

The Long Wharf area is not just influenced by the water of the harbor causing the building foundations to crack and damage the upper floors, but it also has to cope with the strong sea breeze. Standing on the shore, it becomes clear to anyone that the Long Wharf area is constantly fighting a battle with the sea breeze and learning to cope with it. Streets don’t run in any grid pattern, but instead they perpendicular or parallel to the shore throughout the site. The buildings themselves appear to be blown over in the wind, as their heights ascend, as you get more inland, forming a series of rooftops that act almost as steps to the peak of the hill that Boston sits on. This most likely allows for the wind to both get channeled down the streets into the heart of the city to provide a strong breeze, but it also distributed the wind resistance that each building must deal with, and helps the breeze flow over the city as well as through it, instead of hitting a giant wall of steel and glass to allow the city to breathe a little easier. Spirn shares with us that:

“All too often, the builders of cities – government and corporate officials, engineers, architects, landscape architects, and city planners – are oblivious to the effects they have on the urban climate and air quality. Air pollution, discomfort, and energy consumption are treated separately when they are addressed at all, not as the interrelated whole they represent”.

Clearly when dealing with Boston they thought about the whole more than other cities. The city of Boston has always had a deep connection to the ocean and been shaped by it. Even the older buildings of Faneuil Hall are built ascending towards the heart of the city, so people have been taking the sea’s constant blowing into account for over a century.

While the wind coming off the harbor has affected the layout and design of the buildings in the Long Wharf area, it also leaves its permanent mark throughout the site. The first thing that can be noticed upon walking out onto the Long Wharf pier is that the ground is covered in sand. The closer one gets to the ocean, the more sand there is deposited on the streets and sidewalks. One potential source of it all is that it has been blown off of the dunes and beaches of islands in the Boston Harbor and into the city itself. Another argument could be made that the city officials or another group dumped the sand there for some unknown purpose. This, however, would not be able to explain the clear weathering between bricks in the streets and sidewalks that is significantly more evident in areas with a higher sand deposit, implying that the sand is consistently placed in that area and wears away at the bricks.

This weathering is not a unique phenomenon that only appears on the Wharf, but also appears throughout the site. There is clearly visible weathering of the columns of Quincy Market. The sides facing the sea have been worn down and made rough, while the side facing the building is much smoother to the touch. This could have easily been caused by over a century of bombardment by grains of sand carried by the wind. The same weathering appears on the sea-ward face of Faneuil Hall, where one can look to see that the grouting between bricks has been replaced and restored much more recently than it has on any other facing of the building. This shows that, while the people of Boston have clearly thought about how to deal with some parts of the wind, they haven’t thought of it all. Weathering of buildings from sand that is blown in by the wind certainly makes and type of cityscape difficult to maintain in the Long Wharf area. This gradual wearing away of the structures that make up the area is almost certainly imperceptible in real time, taking decades to become noticeable, and most likely does not happen anywhere else in Boston. Yet it is this weathering, combined with the numerous historic buildings of the site, that help to give the Long Wharf and Faneuil Hall their appearances and character that make them what they are today.

Despite all of these forces acting on the buildings of the Long Wharf area, there is more to this part of Boston that the ocean is acting on. Both the Long Wharf and Faneuil Hall are large public areas with heavy pedestrian usage. The City of Boston has seen fit to fill the area with a number of small parks and plots for trees and other plants. The most recognizable of these is the Greenway, which cuts through the site, but also includes the number of trees planted in the Quincy Hall Marketplace and around the coast. The same forces that are constantly shaping the buildings and structure of the city itself are also constantly acting upon all of these organisms.

The trees themselves throughout the site are the most prominent sign of how man has shaped nature, but also how mans creations are shaped by nature. Humanity plants trees in public areas that are intended to look nice, but rarely are the effects of the surroundings taken into account. One noticeable sign of this is along the Greenway. Flanking each side of the sidewalk are trees planted in identical little plots of land, yet the ones on the East side have grown much more prominent than the ones on the West side. Both appear to be the same age, and it seems unlikely that either side was replaced, considering how recently the Greenway was built. Instead, there seems to be two different possibilities as to why one side has flourished while the other has not. The growth of the trees to the East could be associated with their closeness to the sea, and the availability of the sea breeze to them, as they have grown with better access to the wind. This could have meant the trees were exposed to less exhaust from cars and thus allowed them to grow better. The other possibility involves the tall office complex to the West of these trees. When it was built, the Greenway was an interstate highway, and so it didn’t matter how much light it received. Now, the trees to the West of the path live in the shadow of this building for much longer each day than the trees to the East, which could have stunted their growth. The most likely answer, though, is a combination of both. One is a typical problem for urban planners, who sometimes forget how the structures already in place will effect what is going to be built. The other is an example of how nature will interact with new constructs in ways that were unanticipated. Another excellent example of nature affecting the designs of man unintentionally is located in front of the Marriott Hotel on the Long Wharf. The trees there are planted in two rows, and over time the side that faces the open harbor has grown out towards the water, becoming expansive with branches reaching out laterally. The side that faces away from the harbor, on the other hand, has many fewer branches and has grown up in order to reach the breeze that blows over the first row.

These natural forces are constantly at play all come from the interaction of Boston and the Boston harbor. The sea is the driving force behind almost all of the things that have shaped and are currently shaping the Long Wharf and Faneuil Hall area. The ocean seeps into the ground, and through expansion and contraction, has been able to physically change not only the landscape, but also the buildings structures. The wind bearing down off the harbor has also shaped the city, causing the city to be built in a way to better channel the wind through the Long Wharf area. Not only that, but it has physically damaged and changed some buildings in the city and given the entire area and given this part of Boston a certain character of both history and ties to the sea that draws people to it. The ocean and its wind have even shaped the parks and plants that form the urban ecosystem of this section of the city. The city of Boston has always been closely tied to the sea, but the Long Wharf and Faneuil Hall area is closer to the ocean than anywhere else in the city. This area has been dramatically been shaped by the ocean and harbor, and only time will tell where the forces of nature will drive the Long Wharf next.

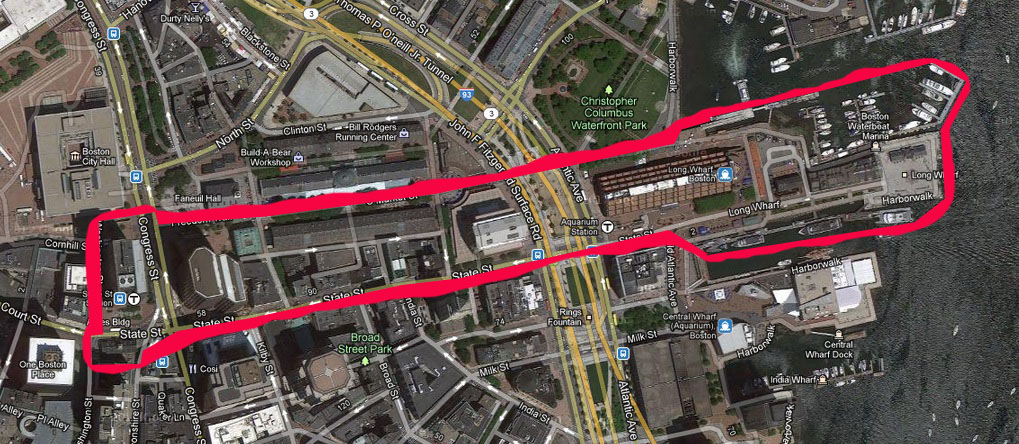

. The Borders of my site

. The Borders of my site

. The curb of the streets as it drops

. The curb of the streets as it drops

. This is the sand that was blown onto the Long Wharf

. This is the sand that was blown onto the Long Wharf

. The trees outside of the Marriott Hotel. Notice how the trees on the right are taller than the ones on the left

. The trees outside of the Marriott Hotel. Notice how the trees on the right are taller than the ones on the left

. This is the building in Quincy Market that has metal supports installed to hold it together

. This is the building in Quincy Market that has metal supports installed to hold it together

. Notice the crack that has formed in the middle arch of this building in Quincy Market

. Notice the crack that has formed in the middle arch of this building in Quincy Market

. The right, sea facing side, of Faneuil Hall is much lighter than the left face. This is because you can tell that it has been replaced very recently

. The right, sea facing side, of Faneuil Hall is much lighter than the left face. This is because you can tell that it has been replaced very recently

. This is the Greenway. Notice the trees on the right are much lower than the left. This is because the left is closer to the sea, and the right is in shade for longer each day

. This is the Greenway. Notice the trees on the right are much lower than the left. This is because the left is closer to the sea, and the right is in shade for longer each day